It is unclear why patients with low back pain seek care in emergency departments.

ObjectivesWe aim to describe the demographic, physical, and psychological characteristics, and reasons for seeking care at emergency departments due to an episode of low back pain.

MethodsThis is a cross-sectional study conducted in an emergency department of a public hospital in São Paulo, Brazil, from September 2018 to May 2019. All patients who presented with a new episode of low back pain as the main complaint for seeking care at the emergency department on regular weekdays were invited to participate. We collected data on sociodemographic characteristics, general health characteristics, psychosocial risk factors, and reasons for visiting the emergency department.

ResultsA total of 200 patients participated. We observed that most patients (68%) were women, with a mean age of 55 years, and who had previous episodes of low back pain (86%). Most patients went to the emergency department because they were worried about their pain (78%) and because they could not control their pain (73%). Patients also choose the emergency department because it is always available, it is free, and provided them good care.

ConclusionsMost patients with low back pain seek care at emergency departments because they were worried about their pain and because the department is always open and does not require appointment. Understanding these reasons is an important step for the implementation of future public policies to make health care more efficient, to reduce unnecessary expenses and to avoid low-value care.

Emergency departments (EDs) aim to provide care to people with acute conditions requiring urgent hospital services.1 The demand for EDs continues to increase by 2–6% per year.2–6 This increase in demand leads to longer waiting times, overcrowding, higher costs, and lower quality of care.7–9 Unfortunately, about 30% of patients visiting EDs have non-urgent complaints and could be managed in primary care.7,10–17 Data from Canada18,19 and the USA20,21 show that low back pain (LBP) is one of the main non-urgent conditions contributing to the overcrowding in EDs. Among the limited information in low-middle income countries,22 the profile of patients with LBP seeking treatment at EDs in Brazil suggest that these patients have high levels of pain intensity and disability.23 Additionally, a cohort study conducted in Brazilian EDs concluded that higher levels of pain and disability are associated with poor outcomes in patients with acute LBP.24,25 A review estimated a LBP prevalence rate of 4.4% in EDs worldwide, similar to other urgent complaints, such as “shortness of breath (4%)” and “fever and chills (4.4%)”.26 Therefore, LBP is one of the main causes of visits to the ED.26

In recent decades, LBP has become a major public health problem.27 But, despite LBP being a large health burden, it has a favorable prognosis.28–30 LBP is one of the top reporting reasons for seeking care at EDs in the USA, with nearly four million admissions per year.31 Usually, when patients with LBP come to the ED they report relatively high pain intensity32 and only 5% present serious spinal pathologies and truly need urgent medical care.33 A number of evidence-based guidelines and models of care have been developed to improve LBP care worldwide.21,22,27,33–37 Despite most guidelines prioritizing non-medical approaches for the management of patients with LBP, it is likely that these patients will receive some kind of medical interventions such as imaging, opioid prescription, or hospital admission; interventions that are not consistent with clinical guidelines recommendations.34

The Brazilian health system proposes that the patient's first contact should take place in primary care. However, it is not uncommon for the ED to be the gateway to the public health system in Brazil.38 Specifically for low back pain, it is important to know the demographic, physical, and psychological characteristics of, and the reasons for patients seeking care in the ED. These data provide important information for the implementation of strategies to improve care so as to decrease the burden on EDs and also for comparisons with future studies in different countries.

MethodsStudy designThis is a cross-sectional study conducted in an ED of a public hospital in São Paulo, Brazil, from September 2018 to May 2019. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Hospital do Servidor Público Estadual and Universidade Cidade de São Paulo (#7,585,517,030,015,463). This manuscript was reported following the STROBE guidelines.39

Eligibility criteriaAll patients who presented with a new episode of LBP as the main complaint for seeking care at the ED on business hours during regular weekdays were screened for eligibility. We used the following acute LBP definition40; “pain in the lower back, with or without referred pain to the lower limbs, lasting between 24 h and 6 weeks and preceded by a period of at least 1 month without pain”.40 Patients were considered eligible if they were between 18 and 80 years of age and seeking care for LBP. Patients who were pregnant or did not understand Portuguese were excluded.

Data collectionFrom September 2018 to May 2019, the Hospital do Servidor Público Estadual treated approximately 1.3 million patients within the state of São Paulo, Brazil. The hospital has 721 beds, 949 doctors, and 2020 health professionals. In this period, a total of 218,291 patients sought care at the ED. From those, a total of 5252 patients (3.5%) had a LBP episode. We recruited a convenience sample of 200 patients with LBP. This study was conducted using the baseline data from a prospective cohort investigating the implementation of a hybrid model for the care of patients with LBP. A member of the research team stayed in the ED from Monday through Friday during business hours. Patients were seen by the physician who conducted the medical consultation following the hospital standard of care and screened for red flags through history taking and physical examination. Shortly, after medical consultation, 206 potentially eligible patients were referred by the physician to the member of the research team who was on location for data collection. A total of six patients did not consent to participate. The physician determined whether or not these patients would be included, according to the eligibility criteria.

Outcome measuresIf the participant agreed to participate in the study by signing the consent form, the researcher collected the data. Patients were interviewed through a structured, in-person verbal questionnaire. Questions were asked and answered under the supervision of the research team member.

Characteristics related to general health, psychological factors, and interferences of pain on work activities were assessed by using items one, six, eight, and 10 of the SF-36.41 We changed the term "bodily pain" to "low back pain" for the purpose of this study. Moreover, questions were adapted as follows: How many days have your LBP forced you to cut down on the activities you usually do? and How many days have you been unable to work? Information on medications prescribed by the physician in the ED was also collected. We also confirmed presence of absence of nerve root compromise through physical examination. Finally, we collected presence of red and yellow flags. Pain intensity, disability, and outcomes of interest are provided in Table 1.

Outcomes of interest and variables related to each outcome.

| Outcome | Variables |

|---|---|

| General Health | Physical activity levels, smoking, bodily pain, and general health perceptions. Question for this outcome: "In general, would you say your health is excellent, very good, good, fair, or poor?" from the SF-36.50 |

| Current and past history of low back pain | Previous episodes of LBP, previous surgeries due to LBP, if LBP appeared suddenly, referred pain to the lower limbs, medication use without medical prescription and duration of symptoms |

| Pain Intensity | Pain intensity was measured with the Numerical Pain Rating Scale (NPRS). The NPRS is an 11-point scale, ranging from 0 (no pain) to 10 (worst pain possible). Participants were asked to report the level of pain intensity perceived based on the last 7 days68,69 |

| Disability | We measured disability with the Roland Morris Disability Questionnaire (RMDQ). The RMDQ has 24-items (yes/no) related to common activities that patients might have difficulty to perform due to low back pain. The total score is determined by the sum of all positive answers. The higher the score, the higher the disability.68–70 |

| Psychological characteristics | Specific items selected from the SF-3650 and from Örebro Musculoskeletal Pain Screening Questionnaire (ÖMPSQ).71 Psychological interference on social activities and feeling about the symptoms of LBP: measured by a 5-point scale ranging between 1 and 5. Stress, anxiety, depression, and risk of LBP become persistent: measured by a 11-point scale ranging between 0 and 10 points. |

| Red flags | Red flags are features of the clinical history, which may be related to a high risk of serious conditions such as malignancy, fractures, and cauda equina syndrome.72 We collected data related to the risk of fracture (eg. previous trauma, advanced age, osteoporosis), malignancy (eg, unexplained weight loss, history of cancer, and night pain), and cauda equina syndrome (eg. progressive motor deficit and anesthesia between the legs, sciatica, or loss of urine).73 The physician made a clinical diagnosis in the medical consultation. In addition, if the patient reported any sign or symptom of neurological impairment or serious pathology, the researcher collected information on red flags.35 |

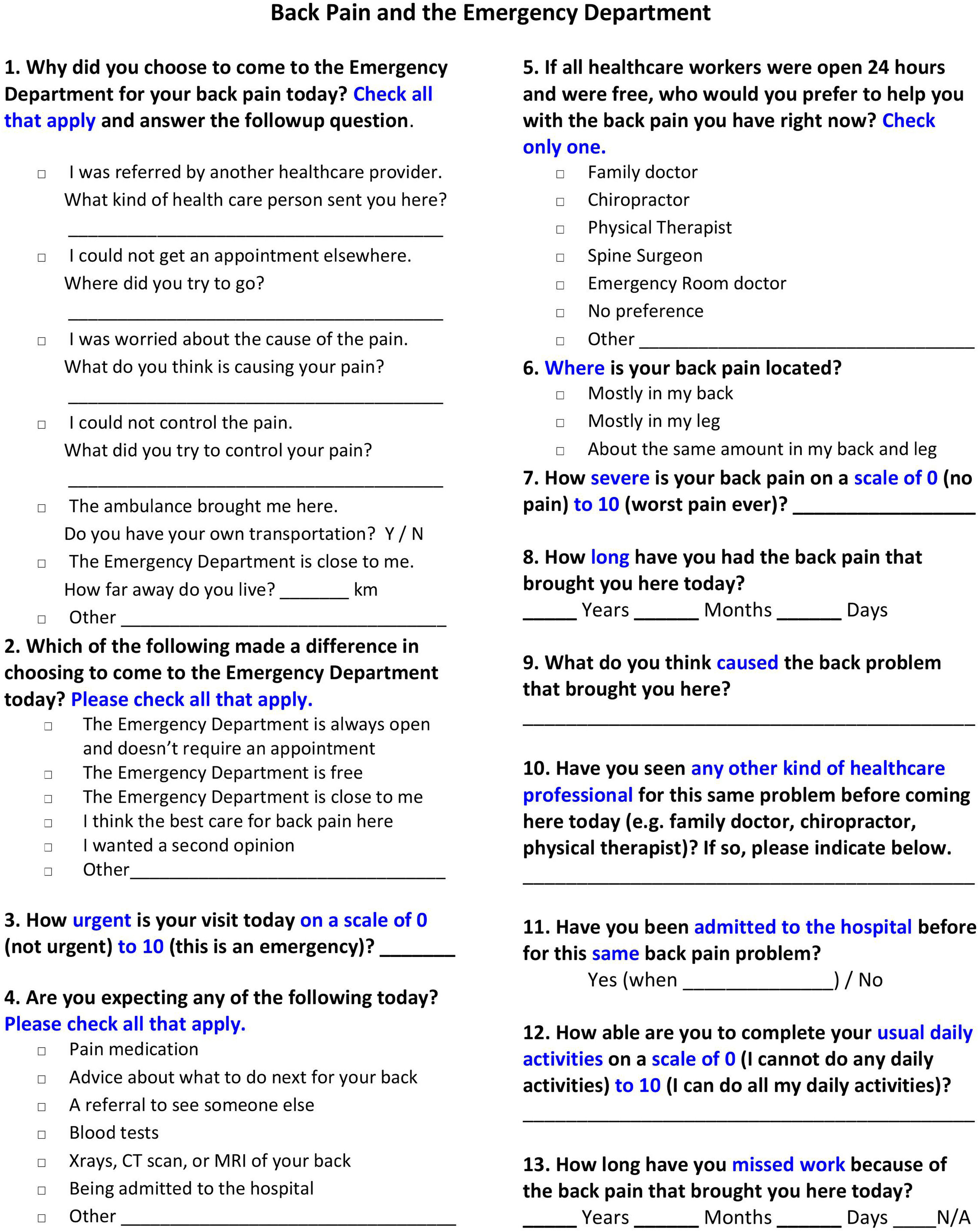

To evaluate the reasons for visiting the ED we used a survey,42 which was composed of 13 independent questions that attempted to explore and understand the motives and reasons why patients with LBP visit the ED (Fig. 1).

The first question is related to why patients chose to visit the ED due to LBP. Patients could choose one or more of 7 pre-defined answer options. Additionally, for each option chosen, a qualitative complementary question was asked so that the answers could be analyzed and grouped later.

The other 12 questions focused on understanding why patients with LBP sought care in the ED. These questions also assessed about patients' beliefs, preferences, and expectations about care received in the ED.

Statistical analysisDescriptive analyses were used to present the characteristics of the patients. Data are presented as mean and standard deviation for continuous variables and frequency and percentiles for categorical variables. All analyses were performed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences version 22.

ResultsData were collected from 200 patients who were seeking emergency medical care. Table 2 shows the demographic and clinical characteristics of the participants. All patients who consented to participate in the study answered all questions. We observed that the majority of patients (68%) were women, with a mean age of 55 years, with previous episodes of LBP (86%), and had a sudden onset of symptoms (74.5%). Mean scores of pain intensity (measured by a 0–10 Numerical Pain Rating Scale) and disability (measured by the 0–24 Roland Morris Disability Questionnaire) were 7.9 and 14.7, respectively. In addition, about a third of the included patients (n = 64, 32%) were considered physically active.

Characteristics of the study participants (n = 200).

| Age (years) | 55.4 ± 12.3 |

| Sex | |

| Female | 136 (68) |

| Weight (kg) | 78.3 ± 18.5 |

| Height (cm) | 165.5 ± 9.7 |

| Education level | |

| Elementary/Middle school | 34 (17) |

| High school | 66 (33) |

| Graduate | 85 (42.5) |

| Post-graduate | 15 (7.5) |

| Duration of symptoms (weeks) | |

| Less than 2 weeks | 114 (57) |

| Between 2 and 3 weeks | 46 (23) |

| Between 3 and 4 weeks | 13 (6.5) |

| Between 4 and 5 weeks | 5 (2.5) |

| Between 5 and 6 weeks | 22 (11) |

| Previous episodes of back pain | 172 (86) |

| Sudden onset | 149 (74.5) |

| Smoker | 18 (9) |

| Previous compensation | 12 (6) |

| Previous sick leave | 45 (22.5) |

| Previous surgery | 5 (2.5) |

| Exercising regularly | 64 (32) |

| Previous medication intake | 127 (63.5) |

| Pain intensity (0–10) | 7.9 ± 1.8 |

| Disability (0–24)* | 14.7 ± 5.3 |

| Prescribed Medications | |

| NSAIDs⁎⁎ | 160 (80) |

| Paracetamol | 17 (8.5) |

| Opioids | 49 (24.5) |

| Muscle Relaxants | 140 (70) |

| Analgesics | 15 (7.5) |

| Corticosteroids | 8 (4) |

| Gabapentin | 6 (3) |

| No medication provided | 20 (10) |

| Psychological characteristics | |

| Psychological interference in social activities (1–5) | 2.7 ± 1.3 |

| Feeling about the symptoms of low back pain (1–5) | 1.2 ± 0.5 |

| Stress and anxiety levels (0–10) | 6.8 ± 3.0 |

| Levels of depression (0–10) | 4.7 ± 3.7 |

| Risk of persistent low back pain (0–10) | 6.0 ± 3.1 |

| Red flags | |

| Night pain | 94 (47) |

| History of osteoporosis | 10 (5) |

| Psychoactive substance abuse | 6 (3) |

| > 50 years old with a history of trauma or > 70 years old | 6 (3) |

| Progressive motor or sensory deficit | 6 (3) |

| Fever, chills, symptoms of infection | 2 (1) |

| Chronic use of corticosteroids | 5 (2.5) |

| Moderate or severe trauma | 3 (1.5) |

| Anesthesia between the legs, bilateral sciatica, loss of urine | 3 (1.5) |

| Intravenous drug use | 3 (1.5) |

| History or suspicion of cancer | 3 (1.5) |

| Therapy failure after 6 weeks of treatment | 2 (1) |

| Unexplained weight loss | 1 (0.5) |

| Immunosuppression | 0 (0) |

Continuous variables are means ± standard deviation and categorical variables presented by frequency (percentage).

For most patients (n = 160, 80%) either NSAIDs and/or muscle relaxant drugs (n = 140, 70%) were prescribed during consultation. Additionally, 63.5% of the patients were already using some medication before consultation.

The apprehension about the symptoms of LBP (i.e.“If you had to spend the rest of your life with the symptoms you have now, how would you feel about it?”) and depression (i.e. “How much has it been bothering you that you've been feeling depressed for the past week?”) were considered low with a mean score of 1.2 and 4.7, respectively. Conversely, the levels of stress/anxiety (6.8), psychological interference in social activities (2.7), and risk of persistent LBP (mean 6.0) were considered moderate to high. We observed that the most prevalent red flag was night pain, which was present in almost half of the sample (47%). The second most prevalent red flag was the presence of a history of osteoporosis (5%), followed by psychoactive substance abuse (3%). Other red flags were less prevalent (≤ 3%).

Table 3 presents the reasons why patients with LBP sought the ED instead of seeking other levels of health care. This table also presents data on patients' expectations and behavior towards LBP and emergency care. Most patients went to the ED because they were worried about their pain (n = 157, 78.5%) and because they could not control their pain (n = 147, 73.5%). The majority of patients (n = 143, 71.5%) chose to go to the ED because it is always open and does not need an appointment. Patients also chose the ED to treat their symptoms because it is free of charge (n = 95, 47.5%) and/or because they believe they can find the best treatment for their LBP at the ED (n = 129, 64.5%). Patients included in this study had a high level of perceived urgency (7.93 ± 1.97).

Reasons to visit the emergency department (n = 200).

Continuous variables are mean ± standard deviation or median (percentile 25th - percentile 75th) and categorical variables are frequency (percentage).

Regarding patients' expectations, 159 (79.5%) patients expected to receive prescription of some pain medication. One hundred patients (50%) expected to undergo imaging exams, 79 patients (39.5%) expected to be referred to another professional, and 76 patients (38%) expected to receive some advice on how to deal with LBP. Only 2.5% of patients had been previously hospitalized due to LBP. The ability to perform daily tasks was moderate with a mean of 5.79.

DiscussionWe aimed to describe the characteristics of patients with LBP and the reasons for seeking treatment in the ED. We observed that most patients were women, with a mean age of 55 years, reporting previous episodes of LBP, and current symptoms of sudden onset. The characteristics of the population in this study are similar to the characteristics of other studies conducted in EDs in Brazil23 as well as in other countries21,25,43,44 with patients presenting moderate or severe pain and disability.21,23,25,43,44 We found that most patients with LBP sought care at the ED because they think that their condition was urgent and believed they were unable to control their pain. Also, our results show that patients choose the ED because it is always available, is free of charge, and provides high-quality care even though most treatments were solely based on medication, which is not consistent with the most recent literature.36

Because patients with non-urgent musculoskeletal conditions seeking care in EDs are quite common, LBP in the ED is a relevant topic, with few relevant publications in the field.23,37,45–48 The strengths of our study are that it brings important considerations into why patients with LBP come to the ED. In addition, many questions used in the survey were created because the data were not part of the usual ED data collection system. This knowledge is important to help implement strategies on how to refer patients to the most appropriate level of care in the future. Moreover, our study contributes to the understanding of this context in a middle-income country with high cultural, socioeconomic, and political diversity.27

Unfortunately, it was not possible to record all LBP visits during the study period. Our study team collected data five days a week from the morning until early evening and we lost data from patients who went to the ED during the evening and on weekends. This study was conducted in a single department, over a limited time window (8 months), and in a metropolitan area. Despite Brazil being a country of continental proportions, São Paulo is the largest Brazilian city and includes people from all Brazilian states with a wide range of social, ethnic, and cultural differences. Nevertheless, perhaps the results could differ in smaller cities or rural areas. More studies are needed to investigate if the reasons for choosing EDs are similar across different countries and cities. Data about previous visit to other levels of care were not collected and should be included in a future study. Another limitation is that our study used a 13-item tool to assess reasons for visiting the ED that was not published and/or validated.

Among the main outcomes, patients' perception of urgency and the convenience of easy access seem to be the main reasons for seeking care in the ED. A qualitative study identified very similar results pointing out the convenience, relief from pain, disability, and anxiety, combined with patient perception and interpretation of the symptoms as a strong influence on the decision to visit the ED.48 A study that aimed to determine the reasons why patients choose to use the ED showed that most patients with non-urgent conditions visited the ED because they did not know anywhere else they could seek care.14 Our study also found that most patients were extremely worried about their LBP (78.5%) and, therefore, selected the ED as their first choice.

A study conducted in the USA recommended that patients with non-urgent conditions should only go to the ED in cases where their primary care providers were unavailable or out of business hours.49 However, most patients with LBP included in our study (64.5%) went to the ED because they considered that this location was the best place to manage their symptoms. Patient health literacy should be developed to shift this behavior.50,51 Convenience seems to be the most common reason in studies that investigated overcrowded EDs.52–55 We observed that many patients consider the ED as a place where they can easily receive free medication, exams, and sick leave. The use of low-value care for patients with LBP is often costly and there is no evidence that it improves outcomes.36,56,57 There is evidence that patient expectations, physicians' concern about missing a serious pathology, and time limitations to perform the clinical examination contribute to the overuse of lumbar imaging.58

Despite scientific and political efforts to reduce the number of visits to the ED, these numbers continue to increase.59 Adding barriers of access to the ED is also unlikely to be effective.59 Initiatives such as improving the supply and care offered in primary care are a good alternative for reducing ED overutilization. In addition, public health literacy campaigns can make a significant contribution, providing education on pain and self-management of LBP.50,59 A study observed a decrease of 30% in ED utilization by offering health literacy to parents who often take their children to the ED.60 However, future studies are needed to identify the best health pathway to manage the symptoms of these patients and align patient and clinician views with LBP guidelines.

In addition, a qualitative study showed that there are some important points to be addressed at the clinical (eg, patient referral, avoiding decisions that exacerbate patient symptoms), patients (eg, comorbidities and chronic diseases, emotions, and expectations), and service (eg, understand the processes and capabilities of ED, availability of physical therapy, and image restriction) levels.61

Understanding this behavior is important to implement measures that can facilitate and guide patients to a more appropriate level of care. Thus, in addition to making the health system more efficient, reducing overcrowding in the ED, and avoiding costs with low-value care, patients can be better oriented in the management of LBP and possible recurrences. Finally, while patients are properly targeted, patients who really need urgent treatment will have priority and greater attention in the ED.

ConclusionMost patients with LBP seek care in EDs because they were worried about their pain and because the department is always open and does not require an appointment. We also found that the patients believe that the ED is the best place to seek care for their LBP. Our findings show important considerations that may contribute to the understanding of strategies to reduce overcrowding in the ED and guide patients to the best level of health care. We also contributed to the understanding of this context in a middle-income country with great socioeconomic, cultural, and political diversity.

This study is funded by the São Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP - Grant 2018/09544–7).