Low back pain is a severe global health problem. To face this issue, testing interventions using rigorously performed randomized controlled trials is essential. However, it is unclear if a country's income level is related to the quality of trials conducted.

ObjectiveTo compare the frequency and methodological quality of randomized controlled trials of physical therapy interventions for low back pain conducted in countries with different income levels.

MethodsThis meta-epidemiological study retrieved trials from the Physiotherapy Evidence Database (PEDro), Literatura Latino Americana em Ciências da Saúde (LILACS), and Scientific Electronic Library Online (SciELO). The methodological quality was evaluated using the 0–10 PEDro scale. Then we calculated the mean differences with a 95% confidence interval and performed an ANOVA test with Bonferroni correction to compare the PEDro scores between income groups.

ResultsWe included 2552 trials; 70.4% were conducted in high-income countries. The mean (standard deviation) PEDro score of all trials was 5.5 (0.03) out of 10. Trials from low- or lower-middle-income countries had lower methodological quality than those from upper-middle- and high-income countries, but the mean difference was small (-0.6 points (95% CI -0.9, -0.3), and -0.7 points (95% CI -1.1, -0.5) respectively).

ConclusionIncome level influences the methodological quality of trials of physical therapy intervention but is not the only factor. Implementing strategies to improve the methodological rigor of trials in patients with low back pain is necessary in all countries, regardless of income level.

Key findings

- •

The methodological quality of trials of physical therapy interventions for low back pain is low.

- •

Trials conducted in low-income countries have lower methodological quality than trials in high-income countries, but the difference is small.

- •

It is unknown what causes the observed differences in the methodological quality of trials. Future studies could investigate those causes and design targeted interventions to improve the methodological rigor of trials conducted in all countries, regardless of income level.

Low back pain is a leading cause of disability, more prevalent in high-income countries than in low- and middle-income countries.1 However, these differences may be partially explained by the lack of high-quality epidemiologic and clinical research in low- and middle-income countries.2 Nevertheless, low back pain dramatically impacts people's lives and health systems regardless of a country's income level.3–5

Despite the high burden across countries, most low back pain research has been conducted in high-income countries.6–9 Research in these countries has systematically excluded people from linguistically diverse backgrounds, with one in five physical therapy trials excluding participants based on language proficiency.10 These two pieces of information raise questions about whether evidence generated in high-income countries is applicable and transferrable to low- and middle-income countries. Among the reasons that explain the underrepresentation of research conducted in low- and middle-income countries are research infrastructure and funding mechanisms.3

Emerging evidence suggests clinicians and researchers have biases toward research conducted in high-income countries.11 Observational studies reveal clinicians and researchers implicitly associate high-quality research with rich countries compared to developing countries.12,13 For example, a recent randomized experiment showed that changing the affiliation of the lead author of a study from a low- to a high-income country positively affected the perception of the relevance of the research and the likelihood of recommending that research to a peer.12,13 Some studies have shown that trials conducted in low-income countries are more likely to have lower methodological quality14 and more commonly report favorable treatment effects15 compared to trials conducted in high-income countries. Furthermore, a few studies have focused on specific differences across methodological quality domains between trials from countries with different income levels.14 According to some authors worldwide, this difference between income levels could be similar in low back pain trials. However, there is a lack of data to support this assumption, and the magnitude of the difference is unknown.16–19

There is an international concern that most interventions reported in guidelines have been tested in high-income countries; some cannot be applicable in contexts with fewer resources because of the different work policies, education access, and health systems.8,16–19 Also, most of these published trials have a low methodological quality,20 so the applicability of these treatments in low- and lower-middle-income countries is questionable. In addition, it is important to know the quality of trials from low- and lower-middle-income countries because low-quality trials represent a waste of scarce resources for research because this information cannot be used in practice or included in systematic reviews.14

The main objective of this meta-epidemiological study was to compare the methodological quality of randomized controlled trials of physical therapy interventions for low back pain conducted in countries with different income levels. Secondary aims were to describe which quality domains were more frequently achieved and the characteristics of the trials (trial design, intervention type used, purpose of the trial, treatment type evaluated) and the participants (age, duration of low back pain, nonspecific or specific diagnosis) in trials from countries with different income levels.

MethodsWe conducted a meta-epidemiological study21 and registered the protocol a priori in the Open Science Framework.22 All data will be publicly available (see Supplementary material).

We hypothesize that the PEDro score of trials of physical therapy interventions for low back pain performed in countries with a high-income level will be higher than that performed in low- and lower-middle-income countries.

Data sourcesSearches were performed in three databases from inception to May 2021. The Physiotherapy Evidence Database (PEDro; pedro.org.au) was the primary database because it is the most comprehensive index of trials evaluating physical therapy interventions.23,24 Literatura Latino Americana em Ciências da Saúde (LILACS) and Scientific Electronic Library Online (SciELO) were also used because PEDro does not include these databases to identify trials for indexing,25 and they are likely to contain trials conducted in low- and middle-income countries in Latin America.26,27 We used the search strategy developed by Cashin et al.20 for PEDro. Health Sciences Descriptors (DeCS) were used to create English, Spanish, and Portuguese search terms for the LILACS and SciELO databases.28 All the search strategies are listed in Supplementary material 1.

Study selectionWe included randomized controlled trials evaluating physical therapy interventions to treat or prevent any low back pain of any duration in participants of any age. The trials included could be of any design on the pragmatic-explanatory trial continuum as long as they used random or intended-to-be-random allocation of participants to groups and were published as full reports in peer-reviewed journals. The physical therapy treatment could be compared to any intervention or control condition.

Protocols and grey literature were excluded. Trials that did not include the country of the institutional affiliation of the corresponding author were excluded. Trials without assessing methodological quality in the PEDro database were also excluded.

Data extractionA customized Excel spreadsheet and detailed guidelines (Supplementary material 2) based on materials used previously by Cashin et al.20 were used for data extraction. These tools underwent three rounds of pilot testing with five reviewers to ensure functionality and consistency between the different data extractors.

Six variables were extracted by a team of 42 reviewers, comprised of both the authors (8 reviewers) and multilingual colleagues (34 reviewers); this team could read articles written in 15 different languages (Chinese, Danish, Dutch, English, French, German, Italian, Japanese, Korean, Norwegian, Polish, Portuguese, Russian, Spanish, and Turkish) to avoid any language restrictions. All data were double extracted, and consensus discussions resolved any conflicts.

Four of the extracted variables were from an existing data set that contained 2215 trials evaluating physical therapy interventions for low back pain.20 The variables were: diagnosis (nonspecific, infection, fracture, inflammatory [rheumatologic condition], radiculopathy, cancer, spinal stenosis, postural changes [pregnancy], osteoporosis, more than one condition, other); duration of low back pain (acute: <6 weeks, subacute:6–12 weeks, chronic:>12 weeks, mixed: more than one duration category, not reported)7; the purpose of the trial (efficacy, effectiveness, efficacy and effectiveness, economic, implementation or translation, unclear); and, type of trial (treatment, prevention, treatment and prevention).

The reviewers extracted two additional variables relating to the country where the trial was undertaken. These were the country of the corresponding author's institutional affiliation and the country from which participants were recruited. We used the country of the corresponding author's institutional affiliation in the analysis because most articles reported this, and this author is strongly involved in the design and conduct of the trial. Additional variables relating to the inclusion criteria were also extracted, but these are reported elsewhere.10

Data downloaded from PEDroFive types of data were downloaded from PEDro: citation details, therapy codes, subdiscipline codes, publication language, and ratings of methodological quality. Codes for therapy and subdiscipline are applied to each article by pairs of trained PEDro raters, with any disagreements arbitrated by a third rater. To facilitate the data analysis, we collapsed the therapy codes into five treatment domains: education (i.e., behavior modification, education, health promotion); passive modalities (i.e., acupuncture, neurodevelopmental therapy, neurofacilitation, orthoses, taping, splinting, stretching, mobilization, manipulation, massage); active modalities (i.e., fitness training, respiratory therapy, skill training, strength training); physical agents (i.e., electrotherapy, heat, cold, hydrotherapy, balneotherapy); and other (i.e., no appropriate value in this field). The subdiscipline code(s) were used to classify trials by age. If the pediatric subdiscipline code was used, the trial was classified as pediatric (≤16 years). If the gerontology code was used, the trial was classified as geriatric (≥60 years). All other trials were classified as adult (17–60 years).

Methodological quality assessmentThe quality of trials was evaluated using the PEDro scale.29 The 11 items included are: eligibility criteria and source, random allocation, concealed allocation, baseline similarity, blinding of subjects, therapists, and assessors, completeness of follow-up, intention-to-treat analysis, between-group comparisons, and reporting point and variability measures. Each item was rated as yes or no. The total PEDro score is calculated by tallying the number of items achieving a "yes", excluding the eligibility criteria and source item, so it ranges from 0 to 10 (the higher scores, the higher quality). For this study, ratings for the 11 individual items and the total PEDro score were downloaded from the PEDro evidence resource (pedro.org.au) for each included trial. Two independent raters generated the scores, with arbitration from a third rater if required. All raters had completed a training program and passed an accuracy test. The PEDro scale has good content validity,30,31 and inter-rater reliability.31,32

Country income levelThe list of countries was categorized by Gross National Income (GNI) per capita published by the World Bank as of July 1, 2020.33 Countries were classified into one of four categories based on the country of the corresponding author's institutional affiliation: low-income (GNI smaller than 1036 USD); lower-middle-income (GNI from 1036 to 4045 USD); upper-middle-income (GNI from 4046 to 12535 USD); and high-income (GNI bigger than 12535 USD). However, we merged the low- and lower-middle-income categories for our analyses due to the small number of included trials conducted in low-income countries, resulting in three income groups: low- or lower-middle-income, upper-middle-income, and high-income.

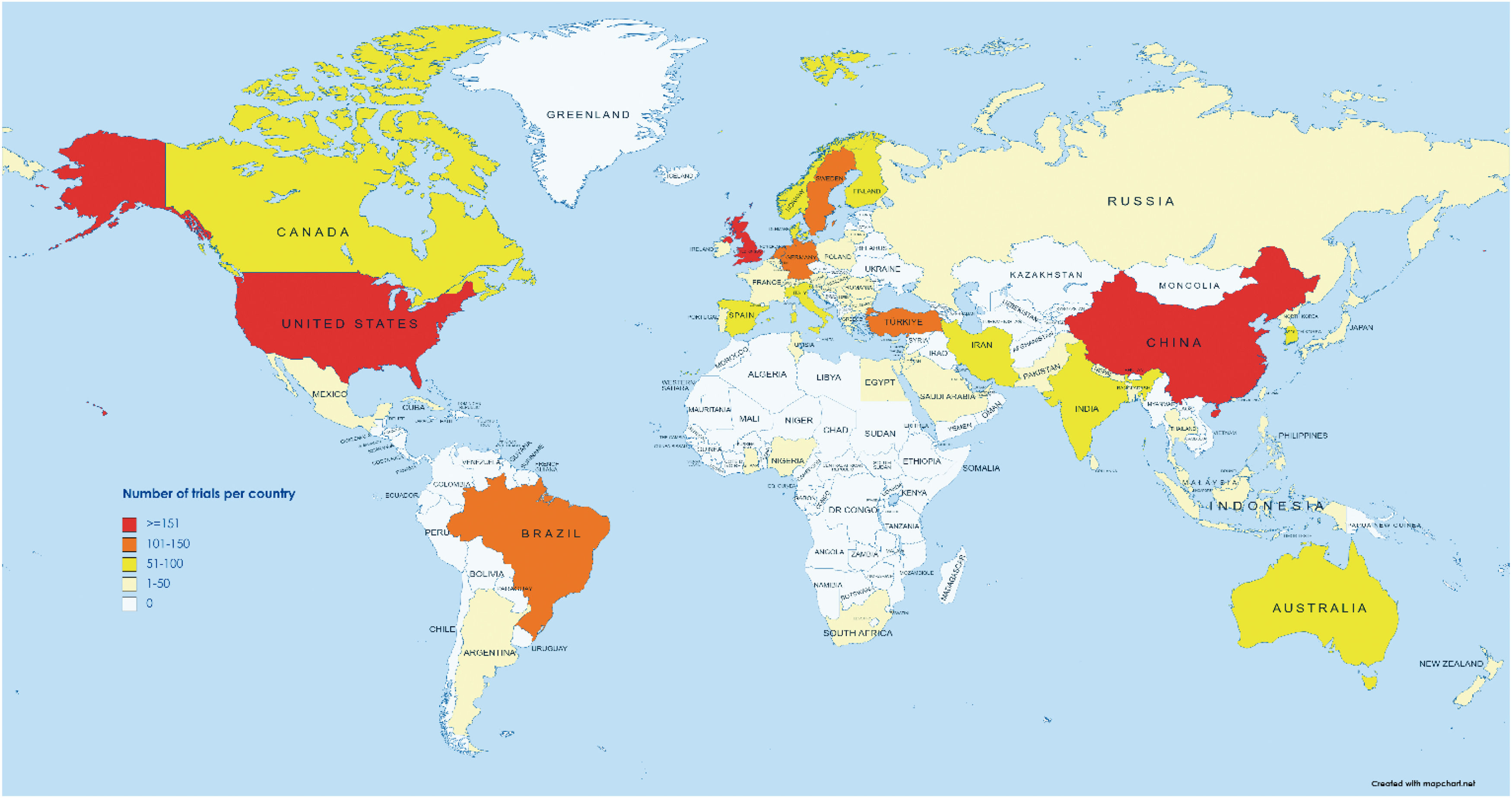

Data analysisThe frequency of trials conducted in each country was tallied and displayed graphically using a heat map (https://www.mapchart.net/world.html). The frequency and percentage of trials for each income group were calculated. Frequencies and rates were calculated for categorical variables. Mean and standard deviation (SD) were calculated for the total PEDro score. A one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni correction to adjust for multiple testing was used to compare total PEDro scores between each country's income level (P = 0.016). Comparisons between country income levels are summarized as mean differences and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI). The number and percentage of achievement was calculated for each PEDro scale item. Chi-square tests were used to determine the difference in percentage achievement of the PEDro scale items for the three income groups; percentage differences and 95% CIs were also calculated. Data were analyzed in Stata v15.1 for Windows (StataCorp, Texas, USA).

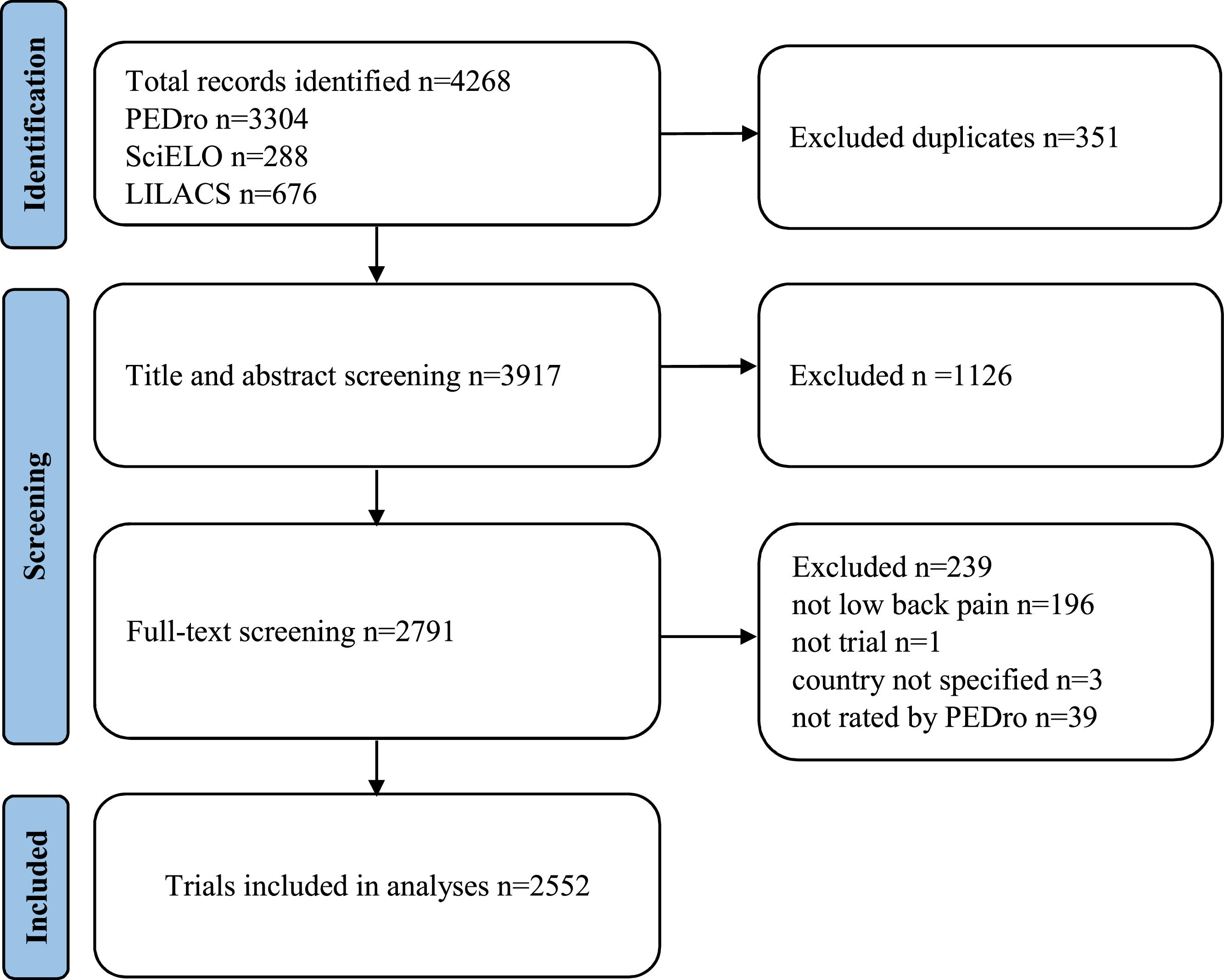

ResultsTrial selectionWe identified 4268 records through searching (Fig. 1). After removing duplicates and title and abstract screening, 2791 records underwent full-text screening. Then, a total of 2552 trials were included.

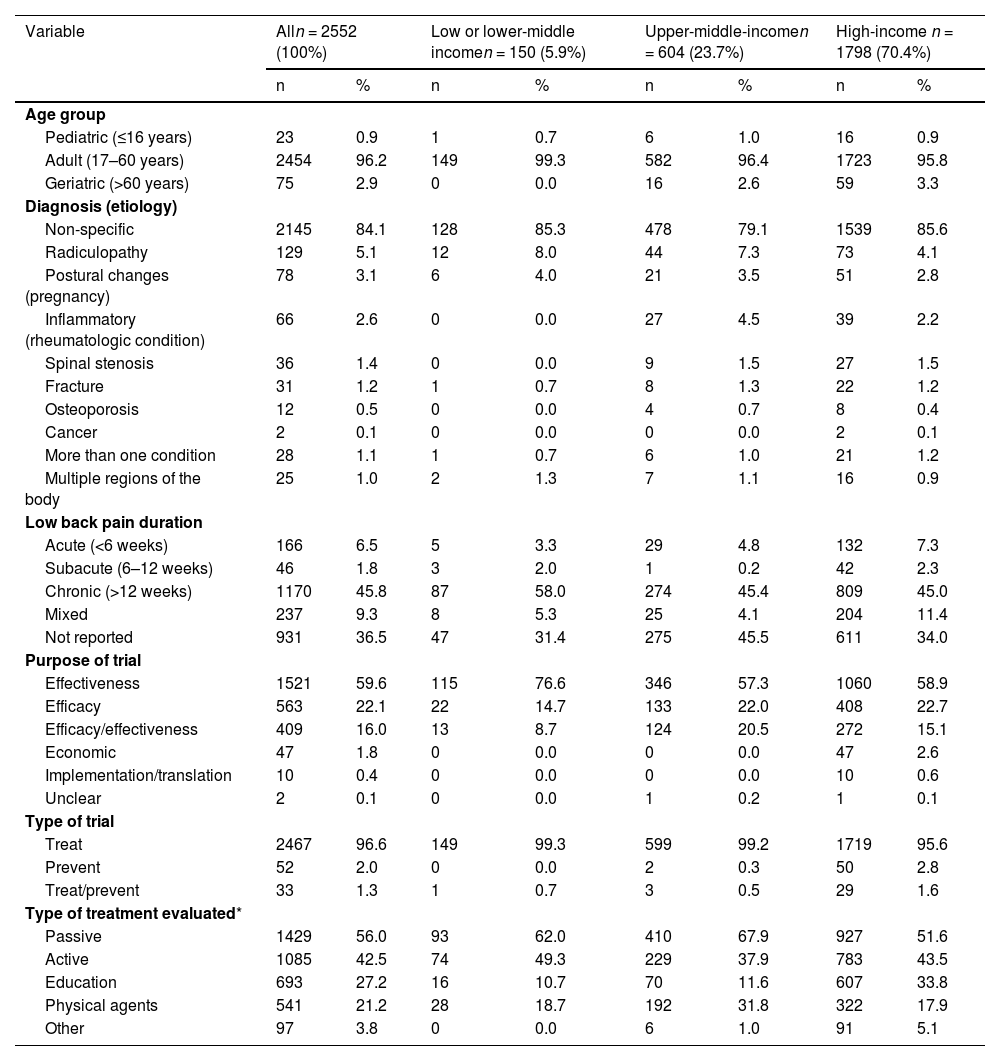

Trial characteristicsTable 1 describes the characteristics of the participants and trials. Most trials (2457/2552; 96.2%) recruited adult participants; nonspecific low back pain was the most reported diagnosis (2148/2552; 84.1%), and chronic pain was the most frequent duration (1171/2552; 45.8%). Effectiveness studies were the most common (1523/2552; 59.6%), and trials with economic evaluation were the least common (47/2552; 1.8%). Physical therapy treatments classified as passive (1430/2552; 56.0%) or active (1086/2552; 42.6%) modalities were the most frequently evaluated in the included trials. Trials from high-income countries were less likely to assess passive modalities and more likely to evaluate education or other treatments than those in low- or lower-middle-income and upper-middle-income countries.

Characteristics of the participants and trials according to the income groups.

| Variable | Alln = 2552 (100%) | Low or lower-middle incomen = 150 (5.9%) | Upper-middle-incomen = 604 (23.7%) | High-income n = 1798 (70.4%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Age group | ||||||||

| Pediatric (≤16 years) | 23 | 0.9 | 1 | 0.7 | 6 | 1.0 | 16 | 0.9 |

| Adult (17–60 years) | 2454 | 96.2 | 149 | 99.3 | 582 | 96.4 | 1723 | 95.8 |

| Geriatric (>60 years) | 75 | 2.9 | 0 | 0.0 | 16 | 2.6 | 59 | 3.3 |

| Diagnosis (etiology) | ||||||||

| Non-specific | 2145 | 84.1 | 128 | 85.3 | 478 | 79.1 | 1539 | 85.6 |

| Radiculopathy | 129 | 5.1 | 12 | 8.0 | 44 | 7.3 | 73 | 4.1 |

| Postural changes (pregnancy) | 78 | 3.1 | 6 | 4.0 | 21 | 3.5 | 51 | 2.8 |

| Inflammatory (rheumatologic condition) | 66 | 2.6 | 0 | 0.0 | 27 | 4.5 | 39 | 2.2 |

| Spinal stenosis | 36 | 1.4 | 0 | 0.0 | 9 | 1.5 | 27 | 1.5 |

| Fracture | 31 | 1.2 | 1 | 0.7 | 8 | 1.3 | 22 | 1.2 |

| Osteoporosis | 12 | 0.5 | 0 | 0.0 | 4 | 0.7 | 8 | 0.4 |

| Cancer | 2 | 0.1 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 2 | 0.1 |

| More than one condition | 28 | 1.1 | 1 | 0.7 | 6 | 1.0 | 21 | 1.2 |

| Multiple regions of the body | 25 | 1.0 | 2 | 1.3 | 7 | 1.1 | 16 | 0.9 |

| Low back pain duration | ||||||||

| Acute (<6 weeks) | 166 | 6.5 | 5 | 3.3 | 29 | 4.8 | 132 | 7.3 |

| Subacute (6–12 weeks) | 46 | 1.8 | 3 | 2.0 | 1 | 0.2 | 42 | 2.3 |

| Chronic (>12 weeks) | 1170 | 45.8 | 87 | 58.0 | 274 | 45.4 | 809 | 45.0 |

| Mixed | 237 | 9.3 | 8 | 5.3 | 25 | 4.1 | 204 | 11.4 |

| Not reported | 931 | 36.5 | 47 | 31.4 | 275 | 45.5 | 611 | 34.0 |

| Purpose of trial | ||||||||

| Effectiveness | 1521 | 59.6 | 115 | 76.6 | 346 | 57.3 | 1060 | 58.9 |

| Efficacy | 563 | 22.1 | 22 | 14.7 | 133 | 22.0 | 408 | 22.7 |

| Efficacy/effectiveness | 409 | 16.0 | 13 | 8.7 | 124 | 20.5 | 272 | 15.1 |

| Economic | 47 | 1.8 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 47 | 2.6 |

| Implementation/translation | 10 | 0.4 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 10 | 0.6 |

| Unclear | 2 | 0.1 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.2 | 1 | 0.1 |

| Type of trial | ||||||||

| Treat | 2467 | 96.6 | 149 | 99.3 | 599 | 99.2 | 1719 | 95.6 |

| Prevent | 52 | 2.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 2 | 0.3 | 50 | 2.8 |

| Treat/prevent | 33 | 1.3 | 1 | 0.7 | 3 | 0.5 | 29 | 1.6 |

| Type of treatment evaluated* | ||||||||

| Passive | 1429 | 56.0 | 93 | 62.0 | 410 | 67.9 | 927 | 51.6 |

| Active | 1085 | 42.5 | 74 | 49.3 | 229 | 37.9 | 783 | 43.5 |

| Education | 693 | 27.2 | 16 | 10.7 | 70 | 11.6 | 607 | 33.8 |

| Physical agents | 541 | 21.2 | 28 | 18.7 | 192 | 31.8 | 322 | 17.9 |

| Other | 97 | 3.8 | 0 | 0.0 | 6 | 1.0 | 91 | 5.1 |

n= number of trials, %= percentage, All= total.

The included trials were conducted in 65 countries. The six most common countries were the United States (398/2552; 15.6%), China (223/2552; 8.7%), the United Kingdom (181/2552; 7.1%), Turkey (114/2552; 4.5%), Brazil (107/2552; 4.2%), and Germany (107/2552; 4.2%). Most of the trials were published in high-income countries (1798/2552; 70.4%), with comparatively fewer trials published in upper-middle income (604/2552; 23.7%) and low- or lower-middle-income countries (150/2552; 5.9%) (Fig. 2).

Methodological qualityThe mean (SD) total PEDro score was 4.8 (1.6) for trials conducted in low- or lower-middle-income countries, 5.4 (1.5) for trials conducted in upper-middle-income countries, and 5.5 (1.7) for trials conducted in high-income countries. Trials conducted in low- or lower-middle-income countries had lower total PEDro scores than trials of high-income countries (mean difference −0.7; 95% CI: −1.1, −0.5) and upper-middle-income countries (−0.6; 95% CI: −0.9, −0.3). Moreover, there was no statistical difference in the total PEDro score between trials conducted in upper-middle-income and high-income countries (−0.2; 95% CI: −0.3, 0.0).

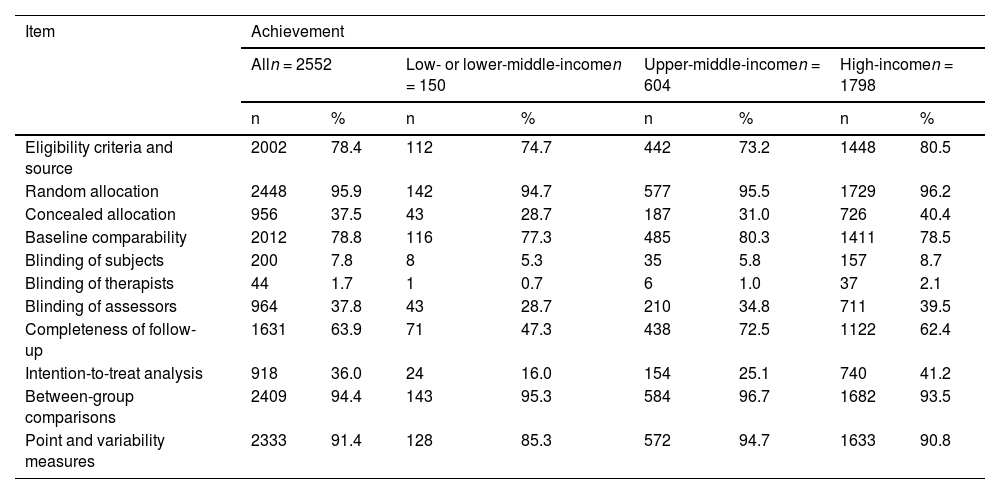

For the individual items of the PEDro scale, the random allocation had the highest achievement (2448/2552; 95.9%), and blinding therapists (44/2552; 1.7%) had the lowest (Table 2).

Frequency of achievement of each PEDro items per income groups.

n= number of trials, %= percentage, All= total.

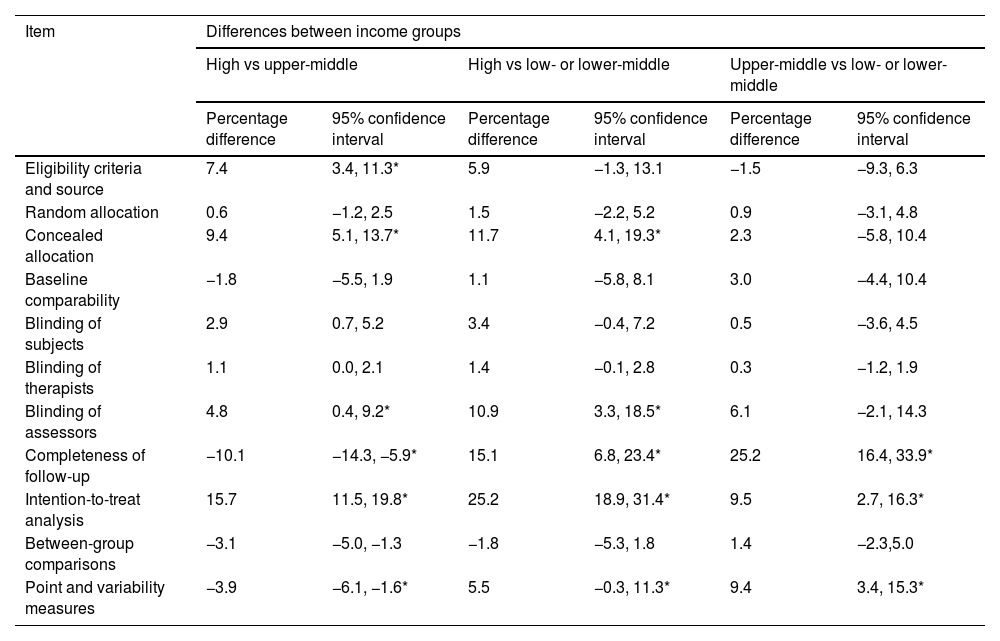

There were statistically significant differences in the achievement of intention-to-treat analysis, completeness of follow-up, concealed allocation, eligibility criteria and source, blinding assessors, and point and variability measures items based on country income level (Table 3). Trials from high-income countries achieved concealed allocation, blinding of assessors, completeness of follow-up, intention-to-treat analysis, and point and variability measures more commonly than trials from low- or lower-middle-income and upper-middle-income countries. Trials from high-income countries achieved eligibility criteria and source more commonly than trials from upper-middle-income countries. Trials from upper-middle-income countries achieved completeness of follow-up, intention-to-treat analysis, and point and variability measures more commonly than trials from low- or lower-middle-income countries.

Differences in achievement of each PEDro items between income groups.

| Item | Differences between income groups | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High vs upper-middle | High vs low- or lower-middle | Upper-middle vs low- or lower-middle | ||||

| Percentage difference | 95% confidence interval | Percentage difference | 95% confidence interval | Percentage difference | 95% confidence interval | |

| Eligibility criteria and source | 7.4 | 3.4, 11.3* | 5.9 | −1.3, 13.1 | −1.5 | −9.3, 6.3 |

| Random allocation | 0.6 | −1.2, 2.5 | 1.5 | −2.2, 5.2 | 0.9 | −3.1, 4.8 |

| Concealed allocation | 9.4 | 5.1, 13.7* | 11.7 | 4.1, 19.3* | 2.3 | −5.8, 10.4 |

| Baseline comparability | −1.8 | −5.5, 1.9 | 1.1 | −5.8, 8.1 | 3.0 | −4.4, 10.4 |

| Blinding of subjects | 2.9 | 0.7, 5.2 | 3.4 | −0.4, 7.2 | 0.5 | −3.6, 4.5 |

| Blinding of therapists | 1.1 | 0.0, 2.1 | 1.4 | −0.1, 2.8 | 0.3 | −1.2, 1.9 |

| Blinding of assessors | 4.8 | 0.4, 9.2* | 10.9 | 3.3, 18.5* | 6.1 | −2.1, 14.3 |

| Completeness of follow-up | −10.1 | −14.3, −5.9* | 15.1 | 6.8, 23.4* | 25.2 | 16.4, 33.9* |

| Intention-to-treat analysis | 15.7 | 11.5, 19.8* | 25.2 | 18.9, 31.4* | 9.5 | 2.7, 16.3* |

| Between-group comparisons | −3.1 | −5.0, −1.3 | −1.8 | −5.3, 1.8 | 1.4 | −2.3,5.0 |

| Point and variability measures | −3.9 | −6.1, −1.6* | 5.5 | −0.3, 11.3* | 9.4 | 3.4, 15.3* |

Most (approximately 70%) randomized controlled trials evaluating physical therapy interventions for people with low back pain were conducted in high-income countries, this raised the concern that most interventions for low back pain could not be suitable to the context and needs of people from countries with less resources.7,8,16,18,19 Slight differences in methodological quality were observed between income level groups, with trials from low- or lower-middle-income countries having lower total PEDro scores compared to trials from upper-middle-income countries and high-income countries. A more considerable proportion of trials from high-income countries achieved the eligibility criteria and source, concealed allocation, blinding of assessors, intention-to-treat analysis, and point and variability measures items of the PEDro scale compared to upper-middle-income and low- or lower-middle-income countries. Completeness follow-up, intention-to-treat analysis, and point and variability measures were more common in trials from upper-middle-income than low- or lower-middle-income countries. An explanation is that having more economic resources could promote the accomplishment of several characteristics required for a trial with high methodological quality, like research assistants, adequate infrastructure, a multidisciplinary team, access to adequate technology, and enough support from public and academic institutions.8

Our study has the following strengths: We included a large sample size of trials published in 15 languages. A rigorous process was used to evaluate the methodological quality of these trials as we downloaded PEDro scores from PEDro, which means that pairs of trained raters generated scores. Also, other trial data were extracted by pairs of independent reviewers using a pilot-tested spreadsheet and clear written instructions.

On the other hand, the study had some limitations that can underestimate or overestimate the results like the unidimensional assessment of income level based on GNI, so we did not analyze other factors related to economic resources that could influence the quality of trials, like external funding or industry sponsorship, because it is complex to measure these variables in all trials included.

Another limitation is that we used the World Bank income classification of 2020 independently of the year of publication of each trial; this could represent a measurement bias because the income classification of some countries may have changed recently.

Also, the PEDro scale was designed to appraise the methodological quality of randomized controlled trials, so it may underestimate those with the economic evaluations in our study. Nevertheless, less than 2% of trials were classified as economic evaluations, so the impact of this issue might be non-significant in our overall results. In addition, we did not extract other variables related to the methodological quality of trials, like research expertise, use of technology, or institution support, which could explain in different ways the differences found in the quality of trials acting as confounding variables that could be controlled in future studies. Moreover, we only searched articles in three databases using a search strategy that considered three languages, but it is important to note that we did not restrict the trials retrieved by language. One of the databases consulted was PEDro, the most comprehensive database of trials in physical therapy.23,31

Lastly, we recognize that we may have omitted some articles, mostly from low- and lower-middle-income countries, if we consider that most research produced there is written in languages different than English and published in gray literature, local journals, or predatory journals; besides we did not consider the work that is not published, but may have good quality.8,14,34

Our finding that the majority of trials were conducted in high-income countries was similar to trials included in Cochrane reviews that evaluated interventions for hypertension, diabetes, stroke, or heart disease (78%),14 smoking cessation (96%),35 or reported mortality outcomes (76%),15 and bibliometric studies of low back pain research that indicates high-income countries were the most productive.6,36 Factors that may explain the low scientific productivity of low- and middle-income countries include the pressure placed on clinician-researchers to manage a sizeable clinical caseload in the presence of financial constraints,37 a few researchers with enough academic formation, lack of research awareness from the society, failure to publish in scientific journals due to English-language proficiency,8,38 prohibitive publication costs,39–42 and publication bias.8,12,38,43 The low prevalence of low back pain trials from low- and middle-income countries prompted a key recommendation in the Lancet series on low back pain, which recommended that more trials were needed in low-resource settings to identify and design context-specific strategies for managing back pain.7

Trials evaluating physical therapy interventions for low back pain have an average total PEDro score of 5.5 out of 10, consistent with other meta-epidemiological studies that report mean scores of 5.3 for musculoskeletal populations44 and 4.7 for cardiorespiratory populations.45 These studies also report a similar percentage achievement of the PEDro scale items. Gonzalez et al.44 investigated predictors of methodological quality in trials of physical therapy interventions for musculoskeletal conditions, concluding that adherence to reporting guidelines, sample size calculation, fewer primary outcomes, and publication in English were associated with higher methodological quality. However, they did not investigate whether the country's income level was related.

Our finding that there are minor differences in methodological quality for trials conducted in countries with different income levels is consistent with a meta-epidemiological study that investigated associations between country income level and risk of bias for trials included in Cochrane reviews.14 Compared to trials conducted in middle-income countries, trials in high-income countries were more likely to have a low risk of bias, including a lower risk for sequence generation, concealed allocation, and blinding.14 In contrast, the country's income level had little impact on the quality of trials included in Cochrane reviews.35

Regardless of the country's income level where the trial was conducted, we observed that methodological quality was low for low back pain trials. Some barriers are likely to impact the quality of randomized controlled trials,8,46 particularly in low- and middle-income countries. Improving financial and institutional support as well as research training and mentoring, could reduce bias in the trial design and encourage better reporting of outcomes in research articles.8 However, we must be cautious with these recommendations as we need more information about what causes the observed differences.

As a recommendation, researchers could consider using established, freely available resources to improve the quality of their trials (i.e., trial registration,47 Standard Protocol Items Recommendations for Interventional Trials [SPIRIT],48 Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials [CONSORT]49). Funders should invest in multi-country trials to evaluate cost-effective interventions to treat or prevent low back pain and journals could implement strategies to encourage publishing and adequate reporting of trials from low- and lower-middle-income countries like ensure blinded peer-review processes, include editors from diverse contexts, and fair article processing charges to authors from countries with less resources.8 This action could improve the methodological quality of trials of physical therapy interventions in patients with low back pain in countries with any income level.

We recognize that there is a wide range of factors, different from income level, that can influence methodological quality; future research should describe which variables could explain a low quality of trials of low back pain interventions. Furthermore, it is important to know if strategies to improve research training and facilitate access to funding could increase the quality of future trials.

ConclusionThere is a minor difference in the methodological quality of trials of physical therapy intervention for low back pain between the income levels of the countries where these studies were conducted. Moreover, seven out of every 10 trials of physical therapy interventions for low back pain are conducted in high-income countries. Therefore, more trials of physical therapy interventions for low back pain from low- and middle-income countries are needed. Finally, implementing strategies to improve the methodological rigor of trials in patients with low back pain is necessary in all countries, regardless of income level.

CRediT authorship contribution statementCarlos Maximiliano Sánchez Medina: Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Data curation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Project administration. Claudia Gutiérrez Camacho: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Supervision. Anne M. Moseley: Methodology, Software, Investigation, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Xochiquetzalli Tejeda Castellanos: Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing – review & editing, Data curation. Qiuzhe Chen: Methodology, Validation, Investigation, Data curation. Edgar Denova-Gutiérrez: Formal analysis. Aidan G Cashin: Methodology, Validation, Writing – review & editing. Viridiana Valderrama Godínez: Investigation. Akari Fuentes Gómez: Investigation. Ana Elisabeth Olivares Hernández: Investigation. Giovanni E. Ferreira: Methodology, Validation, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

We acknowledge and appreciate the effort of all the 34 volunteers who helped us to extract the data from articles written in languages other than English, Portuguese, and Spanish: Vishwesh Bapat, Yvonne Bergemann, Patrick Colne, Matteo Gaucci, Onca Guadarrama, Matthieu Guemann, Michael Hohmann, Emre Ilhan, Johnny Kang, Ilkim Karakaya, Uta Klamser, Weronika Krzepkowska, Chang Liu, Tim Loeffler, Katinka Maier, Klara Metzger, Takahiro Miki, Alexandr Neginsky, Mia Nyvang, Laura Oesterle, Raymond Ostelo, Sylvia Pellekooren, Maciej Plaszewski, Tiffany Radziwill, Julia Ratter, Mykola Romanyshyn, Claudia Sarno, Sophie Sauer, Julia Scheibe, Erwin Scherfer, Adrian Schuhmacher, Jooeun Song, Olivia Traeris, and Hironobu Uzawa.

This study received no specific grant from public, commercial, or not-for-profit funding agencies. Giovanni E Ferreira holds a National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) fellowship (APP2009808). Aidan Cashin has an NHMRC fellowship (APP2010088).