To explore how causal beliefs regarding non-specific low back pain (LBP) have been quantitatively investigated.

MethodsA scoping review based on the guidelines by the JBI (former Joanna Briggs Institute) was conducted. We searched Medline, Embase, Psychinfo, and CINAHL for relevant studies and included peer-reviewed original articles that measured causal beliefs about non-specific LBP among adults and reported results separate from other belief domains.

ResultsA total of 81 studies were included, of which 62 (77%) had cross sectional designs, 11 (14%) were cohort studies, 3 (4%) randomized controlled trials, 4 (5%) non-randomized controlled trials, and 1 (1%) case control. Only 15 studies explicitly mentioned cause, triggers, or etiology in the study aim. We identified the use of 6 questionnaires from which a measure of causal beliefs could be obtained. The most frequently used questionnaire was the Illness Perception Questionnaire which was used in 8 of the included studies. The studies covered 308 unique causal belief items which we categorized into 15 categories, the most frequently investigated being causal beliefs related to “structural injury or impairment”, which was investigated in 45 (56%) of the studies. The second and third most prevalent categories were related to “lifting and bending“ (26 studies [32%]) and “mental or psychological” (24 studies [30%]).

ConclusionThere is a large variation in how causal beliefs are measured and a lack of studies designed to investigate causal beliefs, and of studies determining a longitudinal association between such beliefs and patient outcomes. This scoping review identified an evidence gap and can inspire future research in this field.

The way people understand pain can influence their conscious or unconscious response to it, thus pain perceptions impact behavior and pain related disability.1,2 This is outlined in the Common-Sense Model which illustrates that people create cognitive representations to make sense of an experience, e.g., when experiencing pain.2,3 The representation of illness is created from developing a coherent understanding across the following belief domains: a) what is this pain? (Identity beliefs), b) what caused this pain? (Causal beliefs), c) what will this pain mean to me? (Consequence beliefs), d) how can I control this pain? (Control beliefs), and e) how long will it last? (Timeline beliefs).1,2 The theory suggests that people try to make a coherent understanding of an illness which drives actions and behaviors in response to that illness.

In low back pain (LBP), qualitative research indicates that causal beliefs can have an immense impact on people's lives and how they manage their LBP.4-7 For instance, believing that LBP is caused by damage or the spine being weak can lead to overprotective behavior that involves avoiding certain movements or valued activities.5-9 Furthermore, such causal beliefs about LBP may be a barrier to modern guideline-based care for LBP, as it seems some patients feel miscast for self-management interventions because it does not match their illness beliefs.10

Multiple questionnaires exist regarding beliefs about LBP, and some include questions reflecting causal beliefs. For instance, the belief that LBP is caused by damage or injury of an organic structure is measured in the Pain Beliefs Questionnaire (PBQ) asking if “Pain is the result of damage to the tissue of the body” and as part of the Back Pain Attitudes Questionnaire (Back-PAQ): “Back pain means you have injured your back”.11,12 Both are examples of single items in questionnaires that investigate multiple domains of beliefs. The widely used illness perception questionnaire (IPQ) also includes causal belief items.13 However, a systematic review from 2018 that investigated the association between IPQ scores and pain and disability among people with musculoskeletal pain did not include causal beliefs because these are not measured on a numeric scale in the IPQ.14

Thus, as summarized above, it seems from qualitative research that causal beliefs may be highly important in LBP and several questionnaires exist to potentially investigate this quantitatively. However, the quantitative measure of causal beliefs seems to be heterogeneous and there is currently no overview of the literature investigating causal beliefs. It is thus unclear what quantitative evidence exists that isolates the importance of causal beliefs in LBP from other belief domains. To investigate if the relationship seen in qualitative studies between causal beliefs and poor outcomes of LBP has been investigated in quantitative studies, we conducted a scoping review to map out this research. The aim was to provide an overview of how causal beliefs regarding non-specific LBP have been quantitatively investigated. The specific objectives were to examine: a) What questions and questionnaires have been used to measure causal beliefs regarding non-specific LBP? b) What types of causal beliefs about non-specific LBP have been identified and how many studies have investigated these beliefs? c) In which type of studies and contexts have causal beliefs about non-specific LBP been measured? and d) What outcomes have been investigated for an association with causal beliefs about non-specific LBP in cross-sectional and longitudinal designs?

MethodsThe protocol for this scoping review was pre-registered at Open Science Framework on December 20, 2021, and is available at https://osf.io/7hezb. The method was based on the instructions provided in the JBI manual of evidence synthesis on scoping reviews, and we reported the review according to the PRISMA-ScR checklist for scoping reviews.15,16

Eligibility criteriaWe included published original scientific papers that measured causal beliefs about non-specific LBP and reported results from this domain that could be isolated from other beliefs domains. Population were adults from non-clinical populations with or without non-specific LBP, health-care providers and clinical (i.e., care seeking) populations of patients with non-specific LBP. We excluded studies testing psychometric properties of questionnaires or transcultural adaptations.

Our interpretation of causal beliefs was conceptualized by the common-sense model, which implies that the perception of what caused LBP should be distinguishable from beliefs that according to the common-sense-model relate to other domains. We defined causal beliefs as: a) a perceived cause of LBP, b) a perceived trigger of a new onset of LBP, or c) a perceived risk factor for LBP. Any quantitative measure or data from quantified text responses capturing a causal belief was included. Thus, studies measuring causal beliefs by text responses were only included if the researchers categorized and quantified the text responses in the studies. Studies that in the abstract mentioned causal beliefs specifically or unspecified beliefs were included for full text assessment. Studies measuring beliefs that were specified as other types of beliefs than causal beliefs (e.g., fear avoidance beliefs or kinesiophobia beliefs) were not included.

Furthermore, only peer-reviewed articles written in English were included. We did not use any restriction on time period.

Search strategyWe searched the following electronic databases: Embase, Medline, PsychInfo, and CINAHL. The search strategy was developed in collaboration with a librarian from University Library of Southern Denmark and was initially developed for Embase and then adapted to the other databases. Keywords and search terms were identified from preliminary searches and reading of articles related to the subject. The search combined words of LBP with words for causal beliefs, using both keywords and subject headings (Supplementary material A). The search was conducted on January 10, 2022.

Selection of sources of evidenceDuplicates were removed in Endnote before uploading citations to Covidence review software (Veritas Health Innovation, Melbourne, Australia) for screening and data extraction. Prior to screening of titles and abstracts the inclusion criteria were tested by the entire review team in a pilot screening of a small test sample of 30 titles and abstracts. Two rounds of pilot screening were completed to achieve the desired 75% agreement threshold.

The screening of titles and abstracts as well as full-text assessments were done double-blinded with SG screening the entire sample and TJ, KB, and JD splitting the sample between them. Disagreements between the reviewers were settled through discussion to reach consensus.

Data charting processThe extracted data included study characteristics (population, setting, country, and aim), causal beliefs measurement tool, causal belief items, and outcomes investigated for cross-sectional or longitudinal associations with causal beliefs. The outcomes investigated were only extracted in cases where the association could be linked to the isolated causal belief item. SG and AK piloted the extraction tool and made modification before moving on to the final extraction. Extraction was done independently by SG extracting the entire sample of studies and AK, TJ, JD, and KB splitting the sample between them.

Prior to data extraction consensus between the review team was made to determine which items from the identified questionnaires were considered causal beliefs (Supplementary material B). Each member independently voted for each item whether they deemed it to measure a causal belief based on face validity. The votes were compared, and disagreements settled by discussions in the entire review team to reach consensus.

Synthesis of resultsData were exported from Covidence and handled in Stata/MP V.17. (StataCorp Texas, USA). Extracted data were organized in tables and visualized in bar charts made in Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA). The causal belief items extracted from the studies were categorized into mutually exclusive categories based upon face validity of the beliefs. The first half of the items were categorized in a consensus forum between SG, JD, KB, and AK. The remaining were categorized by SG whereupon all authors commented and agreed upon the final categorization (for resulting categories see supplementary material C).

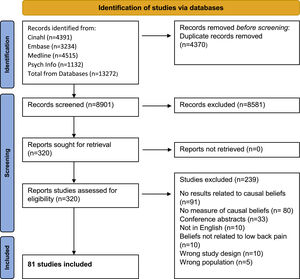

ResultsOf 8901 titles and abstracts screened, 316 were assessed in full-text, and 81 papers were included (Fig. 1). Most exclusions after full text assessment were because the studies did not measure causal beliefs or did not report a result specifically related to the causal belief. Most of the studies (n = 62 [77%]) had cross sectional designs, 11 (14%) studies were cohorts, 3 (4%) randomized controlled trials, 4 (5%) non-randomized controlled trials, and 1 (1%) was a case-control study (Table 1). Beliefs, attitudes, opinions, myths, or perceptions were mentioned in the aim in 44 (54%) studies, and 15 (19%) had an aim specifically mentioning cause, triggers, or etiology. Thirty-three (41%) of the study samples were from the general population, 26 (32%) from health care providers, 13 (16%) from clinical population, 5 (6%) from health-care students, and 4 (5%) studies included mixed populations (Table 1). Most studies were from Western Europe, Australia, or North America.

Characteristics of included studies.

| Study | Country | Population | Design | Categories of causal belief measured | Measurement | Associations investigated |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lindström 199439 | Sweden | General population | Cohort study | LB, LMPC, PWS, PP, MP, EE | Other non-validated | No |

| Christe 202140 | Switzerland | General population | Cross-sectional study | SIP | Back-PAQ-34 | No |

| Pereira 202017 | Portugal | Clinical | Cross-sectional study | IPQ-revised | Cross-sectional: pain intensity, disability, IPQ-domains, suffering, psychology morbidity | |

| Zusman 198441 | Australia | Clinical | Cross-sectional study | SIP | Other non-validated | no |

| Talbott 200942 | United States | General population | Cross-sectional study | LB | Other non-validated | no |

| Dean 201143 | New Zealand | General population | Cross-sectional study | LB, PAS, LMPC, PWD, PP, TM, Gen, GHL | IPQ-brief | no |

| Matsui 199744 | Japan | General population | Cross-sectional study | LB, PAS, PP, TM, Unk | Other non-validated | Cross-sectional: physical work demand |

| Byrns 200434 | United States | Health-care providers | Cross-sectional study | PWD, OWD, Spi, Oth | Modification of Worker attributions scale, and additional questions | no |

| Ree 201645 | Norway | General population | Randomised controlled trial | LB | Deyo's back pain myths | Cross-sectional: days of sick leave |

| Moffett 200020 | UK | General population | Cross-sectional study | SIP, GHL | Other non-validated | Cross-sectional: no back pain, back pain within the past year, consulted General Practitioner for back pain within the last year |

| Keeley 200846 | UK | Clinical | Cohort study | PWD, TM, Unk | Other non-validated | Longitudinal: health related quality of life, number of health care contacts |

| Vargas-Prada 201229 | Spain | Mixed | Cohort study | OWD | Questions adapted from FABQ | Longitudinal: new LBP, new disabling LBP, persistence of LBP, persistence of disabling LBP |

| Scholey 198947 | UK | Mixed | Cross-sectional study | LB, TM | Other non-validated | no |

| Adhikari 201448 | Nepal | Health-care providers | Cross-sectional study | LB, PWD, OWD, PP | Other non-validated | no |

| Battista 202149 | Italy | General population | Cross-sectional study | PAS | Other non-validated | no |

| French 199750 | Hong Kong | Health-care providers | Cross-sectional study | LMPC, PWD, PP | Other non-validated | no |

| Sadeghian 201330 | Iran | Mixed | Cohort study | OWD | Other non-validated | Longitudinal: reporting LBP |

| Alshehri 202051 | Saudi Arabia | Health-care providers | Cross-sectional study | SIP, MP, Unk, | PABS-PT (19-items) | no |

| Christe 202140 | Switzerland | Health-care providers | Cross-sectional study | SIP | Back-PAQ-34 | Cross-sectional: Degree of evidence-concordant clinical decisions for young woman with acute LBP and no sign of serious pathology |

| Ross 201452 | United States | Health-care providers | Cross-sectional study | SIP | Other non-validated | no |

| Werner 200753 | Norway | General population | Cohort study | SIP | Deyo's back pain myths | no |

| Stevens 201654 | Australia | Mixed | Cross-sectional study | LB, PAS, LMPC, PP, SIP, TM, MP, GHL, Oth | Other non-validated | no |

| Fitzgerald 202055 | Australia | Health-care providers | Cross-sectional study | SIP, MP, Unk | PABS-PT-19, ABS-MP, NPQ | no |

| Mehok 201956 | United States | General population | Cross-sectional study | Other non-validated | Cross sectional: body weight treatment recommendations | |

| Benny 202057 | Canada | Health-care providers | Cross-sectional study | SIP, MP, Unk | PABS-PT (19-items) | no |

| Ihlebæk 200422 | Norway | Health-care providers | Cross-sectional study | LB, SIP | Deyo's back pain myths | Cross-sectional: sex, age, profession |

| Ihlebæk 200558 | Norway | General population | Cross-sectional study | LB, SIP | Deyo's back pain myths | no |

| Adams 201359 | United States | Health-care providers | Cross-sectional study | PWD, SIP | Modification of the standardized Nordic Questionnaire | no |

| Boschman 201260 | The Netherlands | General population | Cohort study | OWD | Other non-validated | no |

| James 201861 | Australia | General population | Cross-sectional study | OWD | Other non-validated | no |

| Cherkin 198862 | United States | Health-care providers | Cross-sectional study | SIP, MP, Unk | Other non-validated | no |

| Brennan 200763 | Ireland | General population | Cross-sectional study | LB, PAS, TM | Other non-validated | no |

| Goubert 200321 | Belgium | General population | Cross-sectional study | SIP | Low back pain beliefs questionnaire, specifically developed based on Deyo's myths, TSK, PABS-PT, and the self-care orientation scale | Cross-sectional: pain grade |

| Werner 200864 | Norway | General population | Cohort study | SIP | Deyo's back pain myths | Cross-sectional and longitudinal: Odds ratios for appropriate responses in intervention vs control counties. |

| Walker 200427 | Australia | General population | Cross-sectional study | PAS, OWD, PP, TM | Other non-validated | Cross-sectional: Logistic regression assessing the odds-ratio for care seeking using all other categories as a reference group. |

| Vujcic 201823 | Serbia | Health-care students | Cross-sectional study | PAS, PP, MP, EE, Oth | Other non-validated | Cross-sectional: sex |

| Maselli 202165 | Italy | General population | Cross-sectional study | PAS | Other non-validated | no |

| Patel 201624 | Canada | Health-care providers | Cross-sectional study | SIP | Other non-validated | Cross-sectional: sex, years of practice, hours of practice/week, population size of practice |

| Tarimo 201766 | Malawi | Clinical | Cross-sectional study | LB, PAS, OWD, PP, SIP, TM, MP, GHL, EE, Unk, Oth | Modification of LBP knowledge questionnaire | no |

| Dabbous 202067 | Lebanon | Health-care providers | Cross-sectional study | SIP | Other non-validated | no |

| Ross 201868 | United States | Health-care providers | Cross-sectional study | SIP | Other non-validated | no |

| Lobo 201369 | India | General population | Cross-sectional study | PAS, Gen, GHL | Other non-validated | no |

| Buchbinder 200770 | Australia | Health-care providers | Cross-sectional study | SIP | Other non-validated | no |

| Ulaska 200171 | Finland | General population | Case control study | LB, PAS, PP, EE | Other non-validated | no |

| Foster 200831 | UK | Clinical | Cohort study | MP, GHL, Unk, Oth | IPQ-revised | Longitudinal: disability, global rating |

| Glattacker 201232 | Germany | Clinical | Non-randomised experimental study | Gen, MP, Unk, Oth | IPQ-revised | no |

| Li 202072 | China | General population | Cross-sectional study | PAS, SIP, GHL, Spi | Other non-validated | no |

| Roussel 201673 | Belgium | Clinical | Cross-sectional study | PAS, LMPC, OWD, PP, SIP, TM, Gen, MP, GHL, EE, Unk, Oth | IPQ-revised | no |

| Werner 200874 | Norway | Health-care providers | Non-randomised experimental study | SIP | Deyo's back pain myths | Longitudinal: work in campaign area or in control area |

| Houben 200575 | The Netherlands | Health-care providers | Cross-sectional study | SIP, MP, Unk | PABS-PT (31 items) | no |

| Ostelo 200376 | The Netherlands | Health-care providers | Cross-sectional study | LMPC, SIP, MP, Unk | PABS-PT in its development form | no |

| Lefevre-Colau 200977 | France | Clinical | Cross-sectional study | OWD, PP, TM, | Other non-validated | no |

| Osborne 201378 | Ireland | General population | Cross-sectional study | LB, LMPC, PWD, TM, Unk | Other non-validated | no |

| Igumbor 200379 | Zimbabwe | Health-care providers | Cross-sectional study | LB, LMPC, PWD, OWD | Other non-validated | no |

| Shaheed 201580 | Australia | Health-care providers | Non-randomised experimental study | SIP | Pharmacists Back Beliefs Questionnaire | no |

| Shaheed 201781 | Australia | Health-care students | Non-randomised experimental study | SIP | Modified Back beliefs questionnaire | no |

| Johnsen 201882 | Norway | General population | Randomised controlled trial | LB, SIP | Deyo's back pain myths | no |

| Odeen 201383 | Norway | General population | Randomised controlled trial | LB | Deyo's back pain myths | no |

| Buchbinder 200984 | Australia | Health-care providers | Cross-sectional study | SIP | Other non-validated | Cross-sectional: special interest in LBP |

| McCabe 201985 | Ireland | Health-care students | Cross-sectional study | LB, SIP | Deyo's back pain myths | Cross-sectional: LBP teaching in medical school |

| Wilgen 201386 | The Netherlands | General population | Cross-sectional study | LB, PAS, OWD, PP, SIP, TM, Gen, MP, GHL, EE | IPQ-revised; Other: converted to IPQ R back pain | no |

| Munigangaiah 201625 | Ireland | General population | Cross-sectional study | LB, SIP | Deyo's back pain myths | Cross-sectional: sex, education, age |

| Coggon 201287 | 18 different countries: Brazil, Ecuador, Colombia, Costa Rica, Nicaragua, UK, Spain, Italy, Greece, Estonia, Lebanon, Iran, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, Japan, South Africa, Australia, New Zealand | General population | Cohort study | OWD | Other non-validated | no |

| Darlow 201488 | New Zealand | General population | Cross-sectional study | SIP | Back-PAQ-34 | no |

| Campbell 201318 | UK | Clinical | Cross-sectional study | MP, GHL, Unk, Oth | IPQ-revised | Cross-sectional: pain, disability |

| Steffens 201489 | Australia | Health-care providers | Cross-sectional study | LB, PAS, LMPC, PP, SIP, TM, Gen, MP, GHL | Other non-validated | no |

| Kent 200590 | Australia | Health-care providers | Cross-sectional study | PP, SIP | no | |

| Wolter 201191 | Germany | Clinical | Cross-sectional study | LMPC, TM, Gen, MP, GHL, Unk, Oth | Based on the German Pain Questionnaire | no |

| Christe 202140 | Switzerland | Health-care students | Cohort study | SIP | Back-PAQ-34 | no |

| Campbell 200492 | UK | Clinical | Cross-sectional study | LB, PAS, PP, SIP, TM, Gen, MP, GHL, Oth | Other non-validated | no |

| SilvaParreira 201537 | Australia | Clinical | Cross-sectional study | LB, PAS, LMPC, PP, TM, GHL, EE, Oth | Other non-validated | Cross-sectional: developing acute LBP |

| Igwesi-Chidobe 201726 | Nigeria | Clinical | Cross-sectional study | SIP, Gen, GHL, Spi | IPQ-brief | Cross-sectional: disability |

| Pierobon 202028 | Argentina | General population | Cross-sectional study | SIP | Back-PAQ-34 | Cross-sectional: having seen a health care professional |

| Pagare 201593 | India | General population | Cross-sectional study | LB, SIP | Deyo's back pain myths | no |

| Byrns 200233 | United States | General population | Cross-sectional study | OWD, Spi, Oth | Other non-validated | Cross-sectional: LBP |

| Linton 199338 | Sweden | General population | Cross-sectional study | LB, PWD, OWD, PP, MP | Other non-validated | Cross-sectional: job type, upper management, lower management, blue collar |

| Pincus 200794 | UK | Health-care providers | Cross-sectional study | SIP, MP | ABS-MP | no |

| Leysen 202095 | Belgium and the Netherlands | Health-care students | Cross-sectional study | SIP, MP, Unk | PABS-PT (19-items) | no |

| Bar-Zaccay 201896 | UK | Health-care providers | Cross-sectional study | SIP, MP | PABS-PT (19-items) | no |

| Ihlebæk 200397 | Norway | General population | Cross-sectional study | LB, SIP | Deyo's back pain myths | Cross sectional: living in rural/urban area, age, education |

| Grimshaw 201198 | UK | Health-care providers | Cohort study | OWD, MP, GHL, EE, Unk, Oth | Other non-validated | Cross-sectional: use of radiographs |

ABS-MP, Attitudes to Back Pain Scale in Musculoskeletal Practitioners; Back-PAQ, Back Pain Attitudes Questionnaire; EE, External environment; FABQ, Fear Avoidance Belief Questionnaire; Gen, Genetic; GHL, General health and lifestyle; IPQ, Illness perception questionnaire; LB, Lifting and bending; LBP, low back pain; LMPC, Loading, movement and physical capacity; MP, Mental/psychological; NPQ, Neurophysiology of pain questionnaire; Oth, Other; OWD, Other work demands; PABS-PT, Pain Attitudes Belief Scale for Physiotherapists; PAS, Physical activity and sports; PP, Posture and position; PWD, Physical word demands; SIP, Structural injury/impairment; Spi, Spiritual; TM, Trauma mechanism; TSK, Tampa Scale of Kinesiophobia; Unk, Unknown.

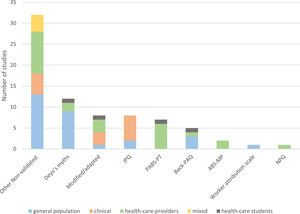

We identified the following questionnaires from which causal beliefs were obtained: Pain Attitudes and Belief Scale for Physiotherapists (PABS-PT) (7 studies) in which 7 items were deemed to be causal beliefs, Back pain attitudes belief scale (Back-PAQ) (5 studies, 2 items), Illness Perception Questionnaire (IPQ) (8 studies, 1 section), Attitudes to Back Pain Scale in Musculoskeletal Practitioners (ABS-MP) (2 studies, 1 item), Neurophysiology of pain questionnaire (NPQ) (1 study, 5 items), and the Worker Attribution Scale (WAS) (1 study, 1 section). Additionally, questions based on two of “Deyo's myths” regarding low back pain were used in 12 studies. For the remainder of the studies, eight measured causal beliefs using modification or adaptations of other questionnaires and 32 measured causal beliefs by other non-validated questionnaires or items specifically developed for the purpose of the study. Fig. 2 shows the use of the measurements within the investigated populations.

The frequency of used questions / questionnaires distributed by population. ABS-MP, Attitudes to Back Pain Scale in Musculoskeletal Practitioners; Back-PAQ, Back pain attitudes belief scale; IPQ, Illness Perception Questionnaire; NPQ, Neurophysiology of pain questionnaire; PABS-PT, Pain Attitudes and Belief Scale for Physiotherapists.

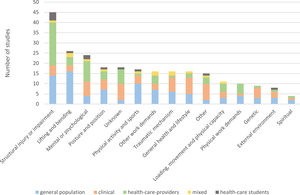

A total of 308 unique causal belief items were identified and categorized into 15 mutually distinct categories. All categories are explained in Table 2, and an in-depth description of items included in each category can be found in Supplemental Material C: Full list of items. The most prevalent investigated category was causal beliefs related to “structural injury or impairment”, which was investigated in 45 (56%) of the studies. The second and third most prevalent categories were related to “lifting and bending“ (26 studies [32%]) and “mental or psychological” (24 studies [30%]) (Fig. 3).

Categories of causal beliefs.

Among the frequently used questionnaires, PABS-PT contained items from the categories “structural injury or impairment”, “mental or psychological”, and “unknown”. Back-PAQ contained only items from “structural injury or impairment”. The questions based on Deyo's myth contained items from “structural injury or impairment”, “lifting and bending”, and “unknown”. IPQ had, due to its free text option, the capability to contain all the categories of causal beliefs created for this review.

Outcomes investigated for an association with causal beliefsTwenty-eight studies investigated an association between causal beliefs and other factors. Twelve studies (43%) were conducted in the general population, 6 (21%) in clinical populations, 6 (21%) among health-care providers, 2 (7%) in mixed populations, and 2 (7%) among health-care students. Cross-sectional associations were reported in 22 studies (Table 1). The most common cross-sectional associations investigated were with pain,17-21 sex,22-25 disability,17,18,26 and care seeking.20,27,28 Longitudinal associations were investigated in 8 studies. The longitudinal association most commonly investigated was reporting LBP29,30 (Table 1).

DiscussionThis scoping review investigated how causal beliefs regarding non-specific LBP have been quantitatively investigated in peer reviewed scientific literature. Eighty-one studies were included accounting for 308 unique causal belief items categorized into 15 categories. Causal beliefs were most often investigated in high-income countries and most often in the general population followed by populations of health-care providers and clinical populations. The most frequent causal beliefs investigated related to structural injury or impairment, lifting and bending, and mental or psychological factors. We identified the use of 6 questionnaires from which a measure of causal beliefs could be obtained. Most of the included studies used cross-sectional designs, and 28 investigated an association between causal beliefs and other factors. Only 8 studies investigated a longitudinal relationship.

Among the questionnaires identified, only the IPQ, PBQ, and WAS were developed with the purpose of specifically measuring causal beliefs.11,13,33,34 However, in our review we did not find any study that reported results related to the causal belief items of the PBQ in isolation, and thus no studies using the PBQ were included. The PBQ consists of two subscales differentiating between organic and psychological beliefs, however these scales include both causal beliefs and consequence beliefs and therefore did not meet our criteria for separate information on causal beliefs.11 The PABS-PT and Back-PAQ were not developed to specifically measure causal beliefs.12,35 Yet we deemed both to have items measuring causal beliefs, and several studies using either PABS-PT or Back-PAQ were included in our review.

Although 81 studies were included, only 15 had an aim that specifically mentioned cause, triggers, or etiology. This indicates a lack of studies that are designed to investigate causal beliefs. Additionally, only 8 studies investigating longitudinal associations with causal beliefs were included in our review. In contrast, a 2019 Cochrane review of recovery expectations (Timeline beliefs) in people with LBP included 52 longitudinal studies for a narrative synthesis.36 Thus, it seems that expectations beliefs have been more thoroughly investigated than causal beliefs.

Causal beliefs appear to be essential for the construct of illness beliefs.1,4,5,7,9 However, to determine the clinical contribution of causal beliefs it is necessary that they are measured and reported in consistent ways. This would help quantify a proposed behavior reaction based on causal beliefs. The findings of this study illustrates that this can be challenging with the current existing evidence due to the large variation in the measure of causal beliefs. The variation additionally implies that causal beliefs are complex and often interacts with other types of beliefs to make up an illness representation.

Strengths and limitationsThe review followed a stringent method and was reported in accordance with current guidelines to ensure high transparency with the choices made in the process. A main concern was that it is not clear cut what constitutes a causal belief, and we consider it a strength that our definition of causal beliefs was based on the common-sense model and the question “what caused my LBP” or “what causes LBP”. However, in the review process we realized that beliefs related to triggers of back pain and contributing factors relate to this domain and thus were eligible for inclusion. For instance, the question “what do you believe may have triggered your LBP?”37 and also questions where participants rated how important they believed different items were in causing back pain, were both deemed to be a measure of causal beliefs.38 As these types of beliefs were discovered in the review process, specific search terms for these were not included in our search strategy. We acknowledge that relevant studies may have been missed on this account, but do not consider this a major flaw because we used a broad search strategy and screened a large number of studies.

We were strict on not including aggravating factors as causal beliefs. However, aggravating factors overlap with causal beliefs. For instance, the item from Back-PAQ “Stress in your life (financial, work, relationship) can make back pain worse” was deemed as measuring aggravating factors and not as a causal belief. This distinction may have favored biomedical beliefs and specific structural causes of LBP while items reflecting psychosocial causes may more often be presented as aggravating factors than as an initial cause. It can be argued that a focus on “contributing factors” to LBP would have been more inclusive but would also make the differentiation from other belief domains less clear. The overlap between domains made the isolation of causal beliefs challenging in some studies. Additionally, many studies had a vague description of methodology and how they measured beliefs. Thus, some subjective interpretation was inevitable.

We did not look for gray literature as we decided to limit the scoping review to peer reviewed literature. Thus, additional knowledge regarding measuring of causal beliefs may exist. However, we have no reasons to believe this would change the general findings of this review.

ConclusionWe wanted to explore how causal beliefs regarding LBP have been quantitatively investigated and settle whether there is available evidence to quantify the impact of causal beliefs on outcomes for LBP that has been observed in qualitative studies. Based on the current evidence this is not feasible due to the large variation in measuring causal beliefs and the lack of studies designed to investigate causal beliefs and of studies determining a longitudinal association between such beliefs and patient outcomes. One belief domain does not exist in isolation from others. However, to understand unique contributions of causal beliefs it would be necessary to develop new measurement tools. This scoping review identified an evidence gap and can inspire future research in this field including search strategies and development of relevant questions and questionnaires.

This study was funded by the Danish Foundation for Chiropractic Research and Post Graduate Education (grant number: A2528). The funders had no role in designing or conducting the study.