Hospitalization contributes to functional decline in older adults.

ObjectiveTo assess the relationship between physical performance on admission and functional capacity and functional capacity decline at discharge, and to investigate tools capable of predicting this decline.

MethodsProspective longitudinal study with 75 older adults admitted to a public hospital between July 2021 and February 2022. The independent variable was physical performance evaluated on admission by handgrip strength (HGS) and the Short Physical Performance Battery (SPPB). The dependent variables were functional capacity for basic activities of daily living (BADLs) and instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs) and their decline between admission and discharge. Statistical analyses were performed using linear and logistic regression and ROC curves.

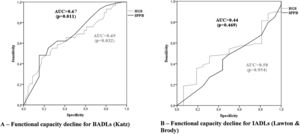

ResultsThe median time between admission and participant assessment was 1 day (IQR=1–2 days). Median hospitalization time was 18 days (IQR= 7.5–30 days). Functional capacity for BADLs and IADLs declined in 39% and 79% of the participants, respectively. Performance in HGS and the SPPB at baseline, in adjusted models, explained 29.3 to 35.3% of functional capacity at discharge. One additional point in the SPPB decreased the risk of functional capacity decline for BADLs by 20.9% (OR=0.79, 95% CI: 0.68, 0.91). The AUC values for the SPPB (AUC=0.67) and HGS (AUC=0.65) were significant in identifying functional decline for BADLs, but not IADLs.

ConclusionIn Brazilian older adults, physical performance on admission was related to functional capacity and its decline at discharge. Physical performance on admission is predictive of functional decline at discharge.

Aging is a universal, multifactorial, progressive process that occurs gradually, causes impairment1 and includes psychosocial and economic factors. It leads to a physiological decline in all body systems, contributing to reduced physiological reserve1 and making individuals susceptible to disability and disease. In older adults, adverse health conditions contribute to functional decline.2 This decline is a determining factor in negative health outcomes, including functional dependence, falls, institutionalization, hospitalization, and risk of death.3

The main causes of hospitalization in this population are cardiorespiratory diseases and orthopedic injuries,4 which contribute to extended length of stay that involve patients spending 83% of their time lying in bed.5 Bed rest exacerbates the negative effects of hospitalization on body systems, including psychological and cognitive aspects.6,7 These negative effects contribute to reduced physical performance and functional capacity for activities of daily living (ADLs) at discharge and in the long term.2,8,9

Functional decline after hospitalization affects approximately 30% of older adults.10 Research indicates that this decline seems to be associated with poor gait speed, balance, and muscle strength at admission2,9 and that performance in handgrip strength (HGS) and the Short Physical Performance Battery (SPPB) at baseline could predict this decline.9,11-14 Elucidating the relationship between physical performance at admission and functional capacity decline during the length of stay in Brazilian older adults is important in helping health professionals make decisions about interventions that can prevent this decline and improve healthcare outcomes. However, the relationship between physical performance at baseline and decline in functional capacity in Brazilian older adults remains unclear. Furthermore, in international studies, only one study, in non-hospitalized older adults, assessed the predictive capacity of both HGS and the SPPB in the emergence of functional disability.13 Previous studies selected participants based on specific health conditions9,12 and did not exclude those who died, classifying patients who died as disabled,12 which may have produced biased results.

Assessing physical performance on admission and the resulting changes in functional capacity in older adults who use Brazilian public health services would contribute to elucidating the effects of hospitalization. Additionally, investigating the possibility of using geriatric assessment tools in a hospital setting as prognostic factors would help stratification of the population at risk of functional capacity decline and allow public health services in Brazil to establish policies that aim to improve quality of life, optimize care costs, and better manage the negative effects of hospitalization, thereby providing better likelihood for older adults to return to the community after treatment.

The present study aimed to investigate the influence of physical performance level at admission on functional capacity and functional capacity decline at discharge. The secondary objective was to determine whether performance assessment tools used at baseline can be predictive of functional decline. We hypothesized that Brazilian older adults experience functional capacity decline during hospitalization and that physical performance on admission influences functional capacity at discharge. We also hypothesized that physical performance assessment tools can predict this decline.

MethodsStudy designThis was a longitudinal prospective study conducted at inpatient units of the Medical Clinic and Cardiology Clinics of the Hospital Regional do Gama (HRG), a tertiary referral facility in the Federal District (DF), Brazil. Patients were recruited and included in the study continuously between July 2021 and February 2022. Approval was obtained from the Research Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Ceilândia (FCE) and Department of Health of the Federal District (SES/DF) (CAAE 47194621.1.0000.8093 – Protocol no. 5.338.654). The study design followed the recommendations of STROBE (Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology) guidlines.15

ParticipantsSample size was calculated using GPower 3.1.5 software. Based on an odds ratio (OR) of 0.43 for the association between decline in ADLs and physical performance,13 power of 80%, and an alpha error of 0.05, the estimated sample size was 80 older adults.

Individuals aged ≥ 60 years hospitalized for adverse health conditions who were capable of completing the physical performance assessments were included in the study. Excluded were those who failed to comply with any of the four commands (“take a piece of paper with your right hand, fold it in half, and put it on the floor”; “close your eyes”; “write a sentence,” or “copy a drawing”) selected from the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE)16 or who exhibited severe health conditions with clinical and/or hemodynamic instability at assessment, characterized by the presence of changes in blood pressure, heart rate, oxygenation, or biomarkers. Patients with advanced neurological diseases and those who refused to take part were also excluded. All participants provided written informed consent.

Outcomes and data collectionSample characterization variablesThe sample was characterized based on patients’ sociodemographic, anthropometric, and clinical and hospitalization variables, collected using a digital scale, stadiometer, and questionnaire designed for the study. Age, sex, education level, self-reported comorbidities (hypertension, diabetes mellitus, chronic kidney disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and stroke) and body mass index (BMI) were analyzed as possible confounding factors.

Independent variableThe independent variable for the study was physical performance at admission, with HGS and leg strength, static balance, and gait speed considered physical performance variables. These were evaluated using a handgrip dynamometer and the SPPB, tools recognized for their validity and reliability (intraclass correlation coefficient [ICC] 0.83 and 0.98, respectively).17,18

Isometric HGS was measured with a Saehan® hydraulic hand dynamometer (Saehan Corporation, 973, Yangdeok-Dong, Masan, Korea) and expressed in kilograms-force (kgf). The participants were seated with no arm support and instructed to keep the shoulder of the arm being tested in adduction, elbow flexed at 90°, forearm in a neutral position, and wrist in a neutral functional position. The dynamometer was then placed in the hand being tested and a verbal command given to squeeze the handle of the device. Three measurements of the dominant hand were taken at 60-second intervals and the average of the three repetitions was considered for analysis. Participants were allowed to familiarize themselves with the process before the test.19 The cutoff point indicating muscle weakness was determined based on sex and BMI, as suggested by Fried et al.20

Leg strength, static balance, and gait speed were assessed using the SPPB.21 The muscle strength of the lower limbs was assessed by the sit-to-stand test, performed five times. Static balance was determined based on the patients’ ability to maintain the tandem, semitandem, and side-by-side stands for 10 s each. Gait speed was analyzed over a distance of 6 m on a flat surface, with pieces of tape demarcating the beginning and end of the course. The first and last meter were used for acceleration and deceleration and not considered in the analysis. The sum of the scores for these three domains produced the total SPPB score, which ranges from 1 to 12.21

The physical performance tests were applied in random order via a simple draw to prevent a predetermined format from affecting participant performance. The physical performance tests were applied by a trained physical therapist.

Dependent variableFunctional capacity for basic ADLs (BADLs) and instrumental ADLs (IADLs) was evaluated using the questionnaires proposed by Katz et al.22 and Lawton and Brody23 on admission and at discharge. Functional capacity on admission was based on patient self-reports regarding the two weeks before hospital admission.2,9 After discharge, participants or their caregivers were contacted by telephone and asked about their execution of these activities at that time (follow-up). Six BADLs (bathing, dressing, toileting, transfers, maintaining continence, and eating) were assessed, with scores ranging from 0 (total dependence) to 6 (independence).22 The seven IADLs analyzed (meal preparation, housework, managing personal finances, using the telephone, shopping, managing medications, and transportation) were scored between 7 (total dependence) and 21 (independence).23 Both tools are valid and reliable for application in Brazilian older adults (ICC 0.80 and 0.91 [95% CI: 0.71, 0.96]).24,25

Functional capacity decline for BADLs was characterized by a decrease of one or more points in Katz index reassessment at discharge, and for IADLs by a decline of one or more points in the Lawton & Brody score at discharge.26 Participants were monitored until inpatient death occurred or until functional capacity reassessment at discharge. Participants followed until the reassessment of functional capacity at discharge were classified into two groups for each activity level: with and without functional decline.

Data analysisThe sample was characterized by descriptive data analysis with measures of central tendency and variability (mean or median and standard deviation or percentiles), absolute frequency, and percentage. Data distribution was analyzed using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test and identified as non-normal (except for HGS data and continued-use medications). Functional capacity for BADLs and IADLs on admission and at discharge were compared by the Wilcoxon test. Simple and multiple linear regression analyses were performed (adjusted for possible confounding variables) to assess the influence of physical performance at admission on functional capacity at discharge. For each analysis, the principles of residual independence (Durbin-Watson), residual normality, homoscedasticity, and lack of multicollinearity between variables (Variance Inflation Factor - VIF<10 and tolerance >0.1) were followed to meet the assumptions for stepwise regression. Simple and multiple logistic regression analyses were performed (adjusted for possible confounding variables) to assess the influence of physical performance at admission on functional capacity decline for BADLs and IADLs at discharge. Odds ratios (OR) were calculated using 95% CI. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were constructed to assess the ability of physical performance on admission (SPPB and HGS) to differentiate between patients who exhibited or not functional decline in BADLs and IADLs at discharge. The area under the ROC curve (AUC) was calculated for each curve, with 95% CIs. For each tool with statistically significant AUC values, alternative cutoff points were established to try to more accurately identify older adults who exhibited or not functional decline. AUC values between 0.51 and 0.69 indicated poor discriminatory capacity and those greater than or equal to 0.70 satisfactory discriminatory capacity.27 Significance level was set at 0.05 and outliers were not excluded. Missing data were analyzed by pairwise deletion (the cases were still used when analyzing other variables with non-missing values). Statistical analyses were performed using the IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows version 22.

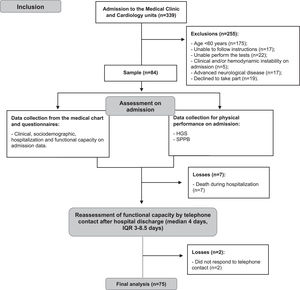

ResultsAll patients admitted to the Medical Clinic and Cardiology units during the study period were assessed based on the eligibility criteria, with 339 undergoing initial screening. Of these, 255 were excluded for not meeting the eligibility criteria or refusing to participate. Eighty-four individuals were assessed based on the clinical, sociodemographic, hospitalization, and physical performance on admission, with 75 completing the longitudinal follow-up at discharge (Fig. 1).

Of these 75 participants, 39 (52%) were from the Medical Clinic and 36 (48%) from the Cardiology unit. The median time between admission to the units and participant assessment was 1 day (interquartile range [IQR]= 1–2 days). Median hospitalization time was 18 days (IQR= 7.5–30 days).

Participants had a median age of 71 years (IQR= 65–78 years) and 4 years of schooling (IQR= 2–11 years), most were sedentary (80%) and earned less than or equal to one minimum wage a month (77.3%). Cardiovascular diseases were the main cause of hospitalization (49.3%). Participant characterization according to clinical, sociodemographic, hospitalization, and physical performance on admission variables is presented in Table 1.

Clinical, sociodemographic, hospitalization, and physical performance characteristics of the study participants at baseline (n = 75).

| Hospitalization variables | |

|---|---|

| Age (years)a | 71 (65–78) |

| Sexb | |

| Female | 33 (44) |

| Male | 42 (56) |

| Education (years of study)a | 4 (2–11) |

| Incomeb | |

| >2 and <9 minimum wages | 17 (22.7) |

| ≤minimum wage | 58 (77.3) |

| Smoking historyb | |

| Current | 8 (10.6) |

| Former | 32 (42.7) |

| Falls in the past yearb | 26 (34.7) |

| Physical exercise in the last 2 monthsb | 15 (20) |

| Continued-use medication (number)c | 4.8 (±3.18) |

| BMIb | |

| Underweight (< 22 kg/m²) | 14 (18.7) |

| Normal weight (22–27 kg/m²) | 28 (37.3) |

| Overweight (> 27 kg/m²) | 33 (44) |

| Comorbidities (number and type)a | 3 (2–4) |

| Hypertensionb | 65 (86.7) |

| Diabetes mellitusb | 34 (45.3) |

| Chronic kidney diseaseb | 18 (24) |

| COPDb | 8 (10.7) |

| Strokeb | 6 (8) |

| Emergency admissionb | 35 (46.7) |

| Place of admissionb | |

| Medical Clinic | 39 (52) |

| Cardiology Clinic | 36 (48) |

| Diagnosis on admissionb | |

| Cardiovascular diseases | 37 (49.3) |

| Pneumonia and other respiratory diseases | 13 (17.3) |

| Kidney disease | 10 (13.3) |

| Stroke and other neurological diseases | 3 (4) |

| Other diagnoses | 12 (16.1) |

| Physical therapy sessions during hospitalization (number)a | 0 (0–5) |

| Length of hospital stay (days)a | 18 (7–31) |

| Functional capacity | |

| BADLs (Katz) (score)a | 5 (5–6) |

| IADLs (Lawton & Brody) (score)a | 20 (17–21) |

| Physical performance | |

| HGS (kgf)c | 22.2 (±9.1) |

| SPPB (score)a | 7 (1–9) |

The median time for functional capacity reassessment was 4 days after discharge (IQR= 3–8.5 days). There was a significant difference in scores of the Katz index and the Lawton & Brody questionnaire at hospital admission and discharge (Katz admission= 5[5–6] vs. Katz discharge= 5 [3–6], p = 0.002 / Lawton & Brody admission= 20[17–21] vs. Lawton & Brody discharge= 14[10–18], p<0.001). Functional capacity for BADLs and IADLs declined in 39% (n = 29) and 79% (n = 59) of the participants, respectively.

Simple linear regression indicated that 18 to 25% of functional capacity for BADLs and IADLs at discharge was explained by physical performance on admission (Table 2). Multiple linear regression adjusted for confounding variables demonstrated that physical performance according to the SPPB and functional capacity for BADLs on admission were related to functional capacity for BADLs at discharge, explaining 35% of this capacity [p = 0.001; R²=0.35]; HGS performance and functional capacity for IADLs on admission were related to functional capacity for IADLs at discharge, explaining 29% of this capacity [p = 0.007; R²=0.29] (Table 2).

Relationship between physical performance and functional capacity at discharge in simple and multiple linear regression models (n = 75).

| Independent variables | R² * | β (95% CI) | Effect size f² (power) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Functional capacity for BADLs | ||||

| Simple linear regression | HGS | 0.19 | 0.09 (0.04, 0.13) | 0.23 (85%) |

| SPPB | 0.25 | 0.23 (0.13, 0.31) | 0.33 (96%) | |

| Multiple linear regression | HGS | |||

| SPPB | 0.17 (0.07, 0.26) | |||

| Age | ||||

| Sex | 0.35 | 0.54 (99%) | ||

| Comorbidities | ||||

| Educational Level | ||||

| BMI | ||||

| BADLs on admission | 0.53 (0.21, 0.84) | |||

| Functional capacity for IADLs | ||||

| Simple linear regression | HGS | 0.19 | 0.22 (0.11, 0.32) | 0.24 (85%) |

| SPPB | 0.18 | 0.47 (0.23, 0.71) | 0.21 (80%) | |

| Multiple linear regression | HGS | 0.15 (0.04, 0.26) | ||

| SPPB | ||||

| Age | ||||

| Sex | 0.29 | 0.41 (98%) | ||

| Comorbidities | ||||

| Educational Level | ||||

| BMI | ||||

| IADLs on admission | 0.43 (0.15, 0.69) |

Simple binary logistic regression showed that performance in HGS (OR=0.94 [95% CI: 0.88, 0.99]) and in the SPPB (OR=0.84 [95% CI: 0.74, 0.95]) on admission was associated with functional capacity decline for BADLs at discharge (Table 3). With multiple binary logistic regression with these two physical performance variables, only the model containing SPPB performance and functional capacity for BADLs at admission was significant (X²=13.075; p= 0.001, R²Nagelkerke=0.217) in predicting functional decline for BADLs at discharge. One additional point in the SPPB reduced the chance of this decline by 20.9% and three additional points by 50.5%. Simple binary logistic regression found no association between physical performance on admission and reduced functional capacity for IADLs at discharge, with only BMI and functional capacity for IADLs on admission as significant predictors (X²=22.851; p= 0.004, R²Nagelkerke=0.407) (Table 3).

Association between physical performance and functional capacity decline at discharge in simple and multiple logistic regression (n = 75).

| Simple logistic regressiona | Multiple logistic regression | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95 %CI) | Β | OR (95 %CI) | Β | Power | |

| Functional decline for BADLs | |||||

| HGS | 0.94 (0.88, 0.99) | −0.06 | |||

| SPPB | 0.84 (0.74, 0.95) | −0.17 | 0.79 (0.68, 0.91) | −0.23 | 27.4% |

| Age | 1.04 (0.98, 1.09) | 0.04 | |||

| Sex | 0.48 (0.18, 1.22) | −0.74 | |||

| Educational level | 1.03 (0.91, 1.15) | 0.03 | |||

| Comorbidities | 0.99 (0.73, 1.32) | −0.01 | |||

| BMI | 0.98 (0.90, 1.05) | −0.02 | |||

| BADLs on admission | 1.27 (0.79, 2.04) | 0.24 | 1.77 (1.00, 3.10) | 0.57 | 97% |

| Functional decline for IADLs | |||||

| HGS | 1.00 (0.94, 1.06) | 0.00 | 1.02 (0.90, 1.16) | 0.02 | 5% |

| SPPB | 1.05 (0.91, 1.19) | 0.04 | 0.85 (0.65, 1.10) | 0.16 | 21.7% |

| Age | 1.02 (0.95, 1.09) | 0.02 | |||

| Sex | 0.71 (0.22, 2.21) | −0.34 | |||

| Educational level | 0.94 (0.82, 1.08) | −0.06 | |||

| Comorbidities | 0.79 (0.56, 1.10) | −0.24 | |||

| BMI | 0.89 (0.80, 0.98) | −0.12 | 0.81 (0.68, 0.95) | 0.21 | 26% |

| IADLs on admission | 1.24 (1.07, 1.43) | −2.48 | 1.42 (1.09, 1.84) | 0.35 | 96% |

Simple logistic regression (enter method). *Statistical significance. bMultiple logistic regression (backward stepwise method) adjusted for the confounding variable BADLs on admission. cMultiple logistic regression (backward stepwise method) adjusted for the confounding variables BMI and IADLs on admission. BADLs, basic activities of daily living; BMI, body mass index (kg/m²); IADLs, instrumental activities of daily living; HGS, handgrip strength (kgf); SPPB, Short Physical Performance Battery (total score).

With the analysis of the ROC curves, the AUC values for the SPPB (AUC=0.67 [95% CI: 0.55, 0.79]) and HGS (AUC=0.65 [95% CI: 0.51, 0.77]) at admission were significant in identifying functional decline for BADLs, but not IADLs (p>0.05) (Fig. 2A and B). Using HGS to predict the risk of reduced functional capacity for BADLs, sensitivity and specificity analyses identified 21 kgf as the most accurate cutoff point in predicting the risk of functional capacity decline in the present sample (sensitivity = 65.5%, specificity = 58.7%, VPP= 50%, and VPN= 73%). When the SPPB was used to predict the risk of functional decline for BADLs, a cutoff of 5 points was most accurate at predicting risk of decline (sensitivity = 62%, specificity = 67%, VPP= 54%, and VPN= 74%).

DiscussionIn this longitudinal study with Brazilian older adults admitted to two clinics at a general public hospital in the Brazilian Federal District (DF), we found that hospitalization negatively affects functional capacity for BADLs and IADLs. Lower HGS and SPPB performances at admission were predictors of functional capacity decline at discharge. Additionally, the results of this study demonstrated that HGS and SPPB performance can be used on admission to screen for risk of reduced functional capacity for BADLs after hospital stay in hospitalized older adults.

Hospitalization contribute to extended periods of bed rest, which lead to physiological changes in the body's systems.6,7 In older adults, among other factors, these changes contribute to reduced muscle strength, physical performance, and aerobic capacity,8 limiting execution of ADLs. In the present study, functional capacity for BADLs declined in 39% of the sample, corroborating previous research that reported reductions in 21.6 to 52.2% of patients.9,10,13,26,28-30 By contrast, to date, reduced functional capacity for IADLs is little studied in hospitalized older adults, with decline reported in 18% of participants28 lower than that detected in our study (79% of patients who declined). These findings reflect the different population characteristics that contribute to limitations in IADLs.31 Factors associated with vulnerability in older adults, such as low income32 and educational levels,33 were present in our sample, which may have influenced the greater number of patients who declined in functional capacity for their IADLs.

The results of the present study also demonstrated that physical performance on admission was associated with functional capacity and functional capacity decline at discharge, corroborating the findings of previous research.2,9,30,34 Other studies demonstrated that older adults with poor physical performance on admission to hospital exhibited significantly worse decline in functional capacity at discharge when compared to those with good physical performance,9 and were 3.19 times more likely to develop limitations in BADLs and IADLs.34 These findings may be associated with the fact that older adults with poor physical performance on admission are more functionally dependent, which tends to increase bed rest time and exacerbate physical losses, contributing to further functional capacity decline.

When considering other factors, only physical performance in the SPPB remained a predictive variable of functional capacity for BADLs at discharge. Good performance in the SPPB reduced the chance of functional decline by 21%, corroborating the findings of a previous study that reported 18 to 20% less likelihood of decline in older adults who performed well in the SPPB.11 The relationship between HGS and functional capacity for ADLs is still debated.12,13,34 Consistent with the present study, another investigation found no association between HGS and functional capacity.13 However, older adults with low HGS had a 1.51 greater chance of functional decline for BADLs34 and those with good HGS on admission were 13% less likely to experience a decline.12 These differences can be attributed to other factors that, in addition to strength, are important in physical performance, such as motor control35 and motor coordination,36 and in functional capacity, including flexibility and aerobic endurance.37

In relation to functional capacity for IADLs at discharge, an association was only observed with HGS. However, this correlation was not strong enough for good HGS performance to lower the risk of functional decline (p = 0.724). These findings differ from previous studies that demonstrated a relationship between HGS and SPPB performance and functional capacity for IADLs.2,9,14,34 IADLs are more complex activities and the ability to perform them depends on factors beyond physical performance, such as educational level, age, sex, engaging in physical activity, comorbidities, continued-use of medication, and income.31 Moreover, in the present study, low BMI was associated with reduced functional capacity for IADLs. Previous results also identified BMI as a predictor of this decline, with limitations in IADLs reported more frequently in underweight older adults.31 This population is more prone to developing sarcopenia and frailty,38 contributing to muscle weakness associated with hospitalization and reduced functional capacity and physical performance.39

Our study also demonstrated the prognostic value of the physical performance assessment tools (HGS and SPPB) in hospitalized Brazilian older adults. The most accurate cutoff points of 21 kgf for HGS and 5 points for the SPPB were considered capable of predicting the risk of decline in functional capacity for BADLs. Unlike previous research that identified an HGS cutoff point of 20.65 kgf only for hospitalized older men,12 the cutoff in our study was suggested for inpatient older adults of both sexes. With respect to the SPPB, our findings are consistent with those of another investigation that also recommended a cutoff of 5 points.11 The sensitivity values recorded in the present study indicated that HGS and the SPPB can detect more than half of individuals at risk of functional capacity decline. Additionally, negative predictive values also demonstrated that older adults who performed well in these tests (HGS >21 kgf and SPPB >5 points) were unlikely to experience functional decline. Although these results are interesting, with cutoff points close to those found in previous research, analyses in the present study are preliminary and showed low predictive capacity, requiring caution in interpreting the results.

In this context, the findings obtained here showed that hospitalization has a significant impact on functional capacity at discharge in Brazilian older adults. In addition, 50% of participants did not undergo physical therapy during their hospital stay, because older adults with a higher level of independence on admission are evaluated and guided to maintain their functioning, but do not receive treatment due to the low number of physical therapists. The lack of physical therapy treatment could accelerate functional capacity decline, because evidence indicates that the more time spent on in-hospital physical therapy, the less functional capacity declines.40 Our results demonstrated that physical performance is predictive of functional capacity at discharge and that HGS and the SPPB can be used as tools to identify older adults at risk of functional capacity decline. They also indicate that the level of independence of older adults for BADLs and IADLs on admission is associated with the ability to perform these activities upon discharge. These findings contribute to targeted care by physical therapists and multiprofessional teams and the implementation of early assessments and interventions, particularly for individuals at risk. These data could also benefit administrators of public health services in Brazil, by demonstrating that strengthening rehabilitation teams in hospital settings will contribute to improving care and lowering healthcare costs, because it promotes functional independence in older adults after discharge when they return to the community.

Limitations of the study were that the research data pertained to older adults with good functional status at admission, admitted to only two inpatient units at a public hospital in the DF, Brazil, and that data on functional capacity at discharge were collected by telephone, in some cases provided by caregivers. The sample size in the present study may have been underestimated, which may have contributed to the low power in some analyses, thus requiring caution when interpreting the results. Future studies should increase the sample size and number of collection sites and devise different strategies for assessing functional capacity at discharge by obtaining a direct report from older adults. Strengths were that participants were not selected based on specific health conditions, favoring generalization of the results, and those who died were not included in the functional decline group. Additionally, all the tools used to collect data exhibit moderate to high validity and reliability.17,18,24,25

ConclusionIn Brazilian older adults, physical performance on admission was related to functional capacity at discharge, indicating that hospitalization contributes to a significant reduction in functional capacity. Physical performance in HGS and the SPPB can be used to screen for older adults at risk of reduced functional capacity for BADLs. These findings reinforce the importance of implementing physical performance assessment measures in hospitalized older adults, making it possible to identify those at risk of functional decline and favoring the adoption of patient care intervention by multidisciplinary teams to minimize this decline.