Pelvic girdle pain (PGP) in pregnancy may result in activity limitations and thus a negative impact on the individual woman's everyday life. Women's expectations when they seek physical therapy because of PGP are not yet known.

ObjectiveTo explore pregnant women's lived experience of PGP and what needs and expectations they express prior to a physical therapy consultation.

MethodsA qualitative study using a descriptive phenomenological method. Interviews conducted with 15 pregnant women seeking physical therapy because of PGP, recruited through purposive sampling at one primary care rehabilitation clinic.

ResultsPGP was described by four themes; An experience with larger impact on life than expected, A time for adjustments and acceptance, A feeling of insecurity and concern, A desire to move forward. PGP had a large impact on the pregnant women´s life. Thoughts of PGP as something to be endured was expressed, the women therefore accepted the situation. Finding strategies to manage everyday life was hard and when it failed, the women described despair and a need for help. They expected the physical therapist to be an expert who would see them as individuals and provide advice that could make their everyday life easier.

ConclusionOur results reveal that pregnant women with PGP delay seeking physical therapy until their situation becomes unmanageable and they run out of strategies for self-care. The women express, in light of their individual experiences, needs and expectations for professional management and advice tailored to their individually unique situation.

Pelvic girdle pain (PGP) is reported by more than 50% of pregnant women and can have a negative impact on everyday life as the pain often results in limited function.1–3 The women may seek physical therapy for treatment and the best evidence interventions are a stabilizing pelvic belt, acupuncture, and physical exercise.4,5

The most common localization of PGP is uni- or bilaterally over the sacroiliac joints and/or pubic bone and the pain may radiate into the thighs.6 PGP could occur any time during pregnancy or within 3 weeks after delivery and symptoms are often related to activity, and walking difficulties, and pain in prolonged standing are common.1,7 Most women recover within 2 months postpartum8,9 but about 20% experience persistent pain 4 months after delivery10 and approximately 10% still experience PGP more than 11 years postpartum.11,12

Women express how PGP limits their functioning in all domains according to the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF).13 Pain also affects their work and social life and result in emotions like anger, frustration, and guilt for not being able to function like they are used to.14,15 Compared to healthy pregnant women, women with PGP have a higher level of anxiety, fear-avoidance beliefs, and depressive symptoms16,17 and an increased risk for postpartum depression.18 Sick leave during pregnancy is needed for 50% of pregnant women, a major reason is PGP19–21 and sick leave may lead to feelings of being excluded from ones usual professional or social context.22

Previous studies show that women request more knowledge, individually tailored advice and treatment, not general information, when they experience PGP.14,15,23,24 Patients with other musculoskeletal disorders expect a professional management, express trust in the physical therapist's competence and knowledge about available treatment options and want to discuss and share decisions about treatment.25,26 Treatment guidelines6 recommend individualized advice and support, exercise, and a pelvic belt but there are currently no evidence regarding if this is what the women need and/or expect when they seek physical therapy. Therefore, our aim was to investigate how pregnant women describe their lived experience of PGP and the needs and expectations they express prior to a physical therapy consultation.

MethodDesignA qualitative study with an inductive, phenomenological perspective, using interviews guided by open ended questions.27 Giorgi's et al.28 descriptive method was chosen for analysis because our aim was to elucidate lived experiences of women with PGP when they seek physical therapy.29,30 The theory of the lifeworld, first described by the philosopher Edmund Husserl (1859–1938), further developed by Dahlberg et al.30 and Giorgi et al.28 was used as a base for interviews and analysis.

Our study was approved by the regional ethical review board in Gothenburg, Sweden (no. 105-16) and reported according to the standards for reporting qualitative research.31 All women got verbal and written information about the study and provided written consent before the interview.

ResearchersThe authors are physical therapists (all female) experienced in qualitative and quantitative research. ASE; PhD-student, clinical experience of treating women with PGP, AG and MFO; specialists in women's health, KM; experienced in phenomenology. AG was the treating physical therapist for all participants and therefore participated only in the last step of the analysis. None of the other authors had any relation to the participants.

ParticipantsPregnant women with self-reported PGP, recruited through purposive sampling at one primary care rehabilitation clinic located in an urban area, representative for a Swedish city regarding ethnicity, age, number of children/women, and socioeconomic status. The participants were recruited from the ordinary consecutive flow of the clinic, no advertising was made. An administrator gave information about the study to women who contacted the clinic to schedule an appointment, and the first author telephoned those who were interested for a first screening of eligibility. Inclusion criteria were PGP that started in pregnancy and ability to understand Swedish in speech and writing. Exclusion criteria were musculoskeletal/systemic disease, any obstetric complication that could contraindicate tests or physical therapy interventions. If the woman agreed to participate, an interview was scheduled, the participants provided written consent before the interview. The interviews were conducted before each of the participant's scheduled first visit to a physical therapist specialized in women's health. The treating physical therapist (AG) confirmed that the woman had clinically verified PGP32 and fulfilled the inclusion criteria. The recruitment stopped when a variety among the women regarding age, gestational week, number of pregnancies, and occupation was obtained. Participant characteristics are provided in Table 1.

Two of the women were born in other European countries; one of them arrived in Sweden as an infant, the other as an adult. All participants were married/cohabitant, and they all had a full/part-time occupation, four women were on sick leave at the time of their interview.

ProcedureIndividual face-to-face interviews (n = 16) were conducted between February 2017 and October 2019 by the first author. Three interviews took place in the women's home, one at the University of Gothenburg and twelve at the rehabilitation clinic before the scheduled consultation. Open ended guiding questions were used to cover the different aspects of the phenomenon (Table 2).

Guiding questions for the interviews.

Follow-up questions and prompts were used when wishing to deepen the description of the women's experiences.30 A pilot interview was performed, some minor adjustments were made regarding phrasing and order of questions, this interview was not included in the analysis. One interview was excluded because the participant had a rheumatic disease affecting the pelvic girdle, leaving 15 interviews included in the analysis. Included interviews lasted for 25–40 min, were de-identified, and transcribed verbatim.

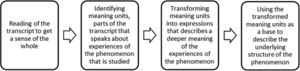

AnalysisData collection and analysis was performed within the phenomenological reduction, which includes the concept of bracketing.28 The researcher should be aware of one's presuppositions and prior knowledge of the phenomenon and put them aside to stay curious and look at the phenomenon with openness from another perspective and not jump to conclusions.33 This was obtained through reflection and discussion among the authors during the iterative process of analysis (Fig. 1).

Process of analysis according to the descriptive phenomenological psychological method by Giorgi et al.30

Two authors (A.S.E., K.M.) checked the transcripts for accuracy and identified meaning units, parts of the text that explicitly or implicitly includes different aspects of the participants’ experience of the phenomenon. Transformation of meaning units from everyday language to expressions with a deeper meaning of the phenomenon was performed by A.S.E. and K.M. individually and discussed together with M.F.O. All authors took part in the final coding, using the transformed meaning units for describing the structure of the phenomenon. During the process, the data and coding was read and re-read, discussed, and revised several times until the final structure could be described.28,33

ResultsThe interviews gave rich narratives of the women's experiences, needs, and expectations, and revealed that PGP had a large impact on the pregnant women´s life including their bodily images and their perceptions of themselves as mothers. Finding strategies to manage everyday life, work, and social life was hard and when it failed, the women described despair and a need for help. In the light of their lived experiences, they expressed a need for a professional examination, to have more knowledge about PGP, and to get individualized interventions based on their unique situation.

The variations in the descriptions that formed the structure of the phenomenon is presented as four themes and their constituents and explained below (Table 3).

Pregnant women's lived experiences of PGP prior to a physical therapy consultation: themes and constituents including quotations.

The number within brackets refer to individual respondents.

The women described PGP as a feeling of discomfort that turned into an unpleasant, disturbing pain which they experienced as a limitation of their ability to move freely, which in turn was experienced as an obstacle in most everyday activities and as a challenge to their social roles as partner and mother.

Being tired of feeling tiredDue to pain, the women experienced difficulties in finding a comfortable sleeping position and thus finding it harder to fall asleep. The women expressed that interrupted sleep affected them during daytime as they felt tired, had less energy, and experienced a decrease in work ability. The insufficient sleep was experienced to create feelings of distress and concern about how to manage through the day, which in turn increased the feeling of tiredness.

Everything is affectedThe experience of having to rely on other people for help made the women feel a loss of independency. They expressed that it was hard to ask for help, emotional and challenging to learn to let go of control and change their way of living. A feeling of incapacity was expressed as the women felt that they could not do anything as they were used to, which led to feelings of concern and fear about how they should cope with the situation if the pain got worse.

The women expressed that their everyday life was gone, they felt exhausted by pain in the evenings, which was experienced as something that affected the relation with their partner. They missed their life as they knew it before pregnancy and the experience of pain and limited functioning gave rise to feelings of frustration and anger, which in turn resulted in feelings of guilt towards their partner or children, so the women sometimes tried to ignore their feelings.

A challenge to the image of motherhoodParticipants who had older children, expressed how they struggled to keep up with their image of motherhood. When the pain affected their ability to care for their children in a significant way, they experienced concern, a fear of being a bad mother, and that their pain would negatively affect the children. If the children went to pre-school, this was experienced as a relief, but it also made the women feel guilty about being selfish leaving their children and not being able to care for them properly.

A need for adjustments and acceptanceThe women appeared to have a solution-focused approach. All their existence appeared to be filled with struggles to manage pain and fulfill their different social roles. Pain, tiredness, and/or other pregnancy complaints took all their energy. They imaged this as a limited period but if the women did not find useful strategies, they experienced feelings of despair and inadequacy.

To navigate through everyday lifeTo manage everyday life without provoking pain, the women had to adjust and plan common daily activities, transports, and work. Taking some time off work to get more time to recover was a strategy used to be able to manage household chores and childcare during the afternoon. Pain was experienced as a punishment for activities during the day when the women had to lay down and rest in the afternoon, which made them experience a feeling of sadness for not being able to function as they were used to.

Adjustments to enable participation in social lifeSome women described how they tried to adjust to be able to participate in a social context without provoking pain. If they could set the rules for the activities, it was possible for them to participate. Others experienced that they accepted the situation, it was only for a limited period and their friends were in the same situation in life. Some women expressed an irritation over the experience of having to put their social life on hold and not seeing any other people than family and close friends. They expressed that they missed their usual activities but stated that after delivery, this would go back to the way it was before pregnancy.

The importance of help and supportThe roles at home changed, as the women took a step back because of pain, their partners and children had to be more active than before. The women experienced gratefulness for having people around them, both at home and at work for support and help with practical issues that they were unable to manage.

A limited period of lifePain was tolerated and endured because the women thought of their situation as a short period of their lives. This attitude made it easier for them to have a positive mindset, even if they expressed that living with pain was hard. They told themselves that it would be worth it when their baby was born and that the pain would disappear after delivery.

A feeling of insecurity and concernTo experience PGP affected the women's independence, their image of self and body, and thus gave rise to feelings such as concern, frustration, and disappointment. The women expressed uncertainty about what caused it, the consequences and if something could be done to relieve their complaints.

Uncertainty about the cause of painA lack of knowledge about PGP and what could be done about it made the women feel concerned and they refrained from activity as they did not know if activity could be harmful. The uncertainty about PGP gave rise to feelings of fear of being disabled or unable to leave home.

Instead of having an active lifestyle, pain, fear of provoking pain, or lack of time was now experienced as barriers for exercise and activities. To refrain from exercise, even if the women knew the benefits of exercise, made them blame themselves and express concern that they themselves had contributed to the pain or to a body that was not strong enough for pregnancy and delivery. This experience of the body being inadequate appeared to result in feelings of resignation and despair.

A changed experience of the bodyThe women experienced a changed image of their bodies and expressed thoughts about the body being worn-out and tired. They experienced their bodies as more noticeable in a negative way that they were not used to, which challenged their image of the beautiful pregnant woman and made them feel disappointed. The experience of not recognizing your own body in either appearance or function was expressed as a tough situation to handle and thus made it hard to enjoy the pregnancy.

A desire to move forwardTo continue life as before pregnancy was a desire expressed by the participants, so they tried to find ways to do the things they wanted to. They stated that it was not an option just to lay down and rest, they appeared to try hard to find ways to manage but realized the need for help when they ran out of strategies. The women requested help to be able to cope with the situation and prevent it from getting worse and they looked forward to the delivery as an end of their struggles.

A need for help when the situation is unmanageableThe women sought physical therapy because they experienced that they no longer could manage the situation on their own and wanted to do all they could to prevent the pain from getting worse, which was a situation they feared. They expressed that they did not want to be seen as weak or whining, or if they really had enough pain to seek care, which appeared to result in them refraining from seeking healthcare until the situation was almost unbearable.

Expectations of being seen as a person in a unique situationThe physical therapy consultation was seen as a chance to meet an expert with vast knowledge and experience who could provide understanding, a thorough examination and individually adapted advice. Half of the women had previous negative experiences of healthcare. Due to experiences of mistrust and being questioned, they expressed low expectations before the consultation. Some of the women got recommendations regarding the rehabilitation clinic from doctors, midwives, or family/friends and this led them to express higher expectations.

To be able to function in everyday life and to be independent were the most important needs expressed by the women and they emphasized that they wanted causal explanations to their pain and advice regarding safe exercise to be able to develop strategies for self-care.

An expectation of the delivery as an end and a beginningThe delivery was imagined as an endpoint of pain and a beginning of something else where the women saw their bodies as something that should be re-built, so they could use their bodies as they wanted and were used to. Most of the women appeared to mentally prepare for different scenarios during the rest of the pregnancy and imagined possible solutions, but some of them appeared to be focused on how to manage their everyday life and did not dare to think about the time ahead.

DiscussionThe results of the present study reveal that PGP means a major interruption in the everyday life of pregnant women and that they delay seeking physical therapy until the situation becomes unmanageable. The women expressed, in light of their individual experiences, needs and expectations for professional management and advice tailored to their individually unique situation.

The impact of PGP on everyday life and the mixed emotions of joy, happiness, and concern about the pain, the baby, and the future expressed by the women in our study, are consistent with findings of previous research.14,15,34 The tiredness, activity limitations and the challenged image of motherhood, affects the women's existence in their lifeworld, their relations, and future plans in different ways. From experiencing good health to experience PGP and limited functioning was something the women were not prepared for, which caused an emotional impact.34 The women's descriptions of PGP include unpleasant sensory and emotional individual experiences, influenced by biological, psychological, and social factors which is in line with how pain is currently defined.35,36 The women's experiences of how everything, i.e. their functioning, was affected can also be understood on the basis of the ICF.13

Experiencing pain and fatigue are defined as impairments on the level of body structure and function in the ICF. The need for adjustments in everyday activities and help from others are defined as activity limitations and the women's limited work ability and/or inability to participate in social activities as restrictions according to ICF.13 Personal factors such as prior experience of pregnancy and/or pain affects how the pain is perceived by the individual as well as environmental factors such as living in a house with no elevator and the availability of support from others.13,14 We suggest that ICF is used as foundation for physical therapists to ensure that all domains of the PGP experience are considered when treatment options are discussed.

The participants expressed insecurity and a lack of knowledge about the cause of pain and how it could be treated. This is described in previous studies on PGP14 and other musculoskeletal complaints.25 The women described how the pain made them feel limited and that their bodies had become more noticeable. This can be understood as when our body is functioning as we are used to, we do not think about it, but when we experience pain, our body becomes more obvious to us, and this may cause concern.37 Fear avoidance-beliefs during pregnancy may predict postpartum lumbopelvic pain,16,38 therefore physical therapy interventions need to address all aspects of the individual woman's pain experience.

Our findings reveal that women with PGP wait until their situation is almost unbearable before they seek help. The cause of this delay may be that pregnancy is seen as a normal condition that a woman should endure or that they fear that their complaints would not be taken seriously.39 The expectation regarding the physical therapist being an expert who would listen, understand, and provide relevant interventions are confirmed in research where patients with other musculoskeletal disorders express trust in the professional physical therapist's competence and want to participate in decisions about treatment.25,26 Our result are consistent with studies40,41 that suggest that a person-centred approach in physical therapy containing listening, communication (verbal and non-verbal), professional skills, individualization of care, and goal setting together with the patient is important for both the therapeutic relationship and the treatment outcomes. The delivery was described as a turning point, the pain would stop and be replaced with something positive. This is a unique aspect about PGP, for most women the pain disappears shortly after delivery8,10 and this notion may explain the participants’ needs for getting advice for self-care.

Individual interviews were found to be a suitable method to get rich descriptions from the participants who spoke freely and sometimes were emotional about their individual experiences. We did not experience the guiding questions as any limitation for this. Transparency of researchers’ characteristics, the process of data collection and analysis consistent to the chosen method, and the findings derived from the data are supposed to strengthen trustworthiness. Any disagreements among the authors during the analysis was thoroughly discussed until consensus was reached. The last author, KM, had limited experience of treating women with PGP, which brought another perspective into the analysis. A strength of the study is that the participants were recruited out of the consecutive flow of one rehabilitation clinic, without any preselection. A limitation is that all participants were recruited from the same clinic. Qualitative research cannot be generalized as it is depending on its context and participants. Although we suggest that the result derived from our analysis could be applied to other pregnant women in a similar setting, the reader must make judgements of transferability.

ConclusionOur study shows that pregnant women with PGP endure pain and delay seeking help until their functioning is limited and their situation becomes unbearable. When they seek physical therapy, they expect individualized advice from an expert. These results indicate a need of more individually tailored physical therapy when treating PGP in pregnancy.

The study was funded by Region Västra Götaland, Sweden no. VGFOUREG-220091, the funder had no role in the design, conduct, or reporting of this study. The authors wish to thank the participating women and the administrative staff that helped with recruitment of participants.