Prescription behavior in low back pain (LBP) differs between physical therapists with a biomedical versus a biopsychosocial belief, despite the presence of clinical guidelines.

ObjectiveTo examine (1) the beliefs of physical therapy students and their adherence to clinical LBP guidelines in Belgium and the Netherlands; (2) whether the beliefs and attitudes of physical therapy students change during education; (3) whether beliefs are related to guideline adherence; (4) whether beliefs and attitudes differ with or without a personal history of LBP.

MethodsA cross-sectional design included students in the 2nd and 4th year of physical therapy education in 6 Belgian and 2 Dutch institutions. To quantify beliefs, the Pain Attitudes and Beliefs Scale, the Health Care Providers’ Pain and Impairment Relationship Scale, and a clinical case vignette were used.

ResultsIn total, 1624 students participated. (1) Only 47% of physical therapy students provide clinical guidelines’ consistent recommendations for activity and 16% for work. (2) 2nd year students score higher on the biomedical subscales and lower on the psychosocial subscale. 4th year students make more guideline consistent recommendations about work and activity. (3) Students with a more biopsychosocial belief give more guideline adherent recommendations. (4) Personal experience with LBP is not associated with different beliefs or attitudes.

ConclusionsA positive shift occurs from a merely biomedical model towards a more biopsychosocial model from the 2nd to the 4th year of physical therapy education. However, guideline adherence concerning activity and work recommendations remains low.

Clinical practice guidelines for the management of low back pain (LBP) recommend healthcare practitioners to evaluate and treat patients within a biopsychosocial framework, recognizing that social, psychological, as well as biomedical factors have significant influences on pain and disability.1–4 This biopsychosocial framework is broadening of the traditional biomedical model, in which pain is largely considered a consequence of tissue damage. A pure biomedical diagnosis cannot be given for the majority of LBP cases. Therefore, guidelines postulate that patients with LBP should be approached from a biopsychosocial perspective,1–4 in which psychosocial factors, such as illness perception, play an important role.

The Common Sense Model (CSM) is a theoretical framework to describe cognitive and emotional responses to illness and symptoms and how a person copes with these sensations. This model relates someone’s perceptions as one of the important determinants of one’s behavior.5,6 Studies on decision-making point out that prescription behavior is determined by healthcare practitioners’ beliefs about the health problem.7 Prescription behavior significantly differs between healthcare practitioners with biomedical versus biopsychosocial background. Healthcare practitioners with a biomedical treatment approach, who have followed biomedical training courses and hold strong beliefs about strict relationships between pain, function, and disability in patients with chronic low back pain (CLBP), generally adhere less to the clinical guidelines for the management of CLBP.8–10 Moreover they advise their patients to restrict work and physical/leisure activities.11 According to a recent study, Belgian physical therapists primarily assess biomedically oriented illness perceptions, but do not sufficiently address psychosocially oriented illness perceptions during history taking.12 At this moment, the origin of these counterproductive beliefs is unclear. One could speculate that professional training is important in building cognitive frameworks with which healthcare practitioners understand complex health problems like CLBP. The educational program lays the foundation of future healthcare practitioners in terms of beliefs and attitudes. Although, some studies investigated the beliefs of health care students,8,13–15 the impact of the beliefs on clinical behavior, or in other words the link with their attitudes, remains unclear.

The CSM not only states that beliefs and attitudes are closely related, but also that perceptions are based on experiences and provided or acquired information.6 Former experiences include, for example, personal experiences with LBP or cultural background.16,17 The latter explains the need to investigate the beliefs of healthcare practitioners in different countries. Moreover, the CSM implies that beliefs can change over time when building new experiences or that they can change when processing new information. Indeed, studies showed that attitudes and beliefs of physical therapists about LBP can change after a training session or lecture.14,18,19 These findings suggest the need to study the attitudes and beliefs of physical therapy students during their education.

Therefore, the purpose of this study was to examine: (1) the beliefs of physical therapy students and their attitudes (their adherence to clinical guidelines in treating patients with LBP) in Belgium and the Netherlands; (2) whether beliefs and attitudes of physical therapy students change from the second to the fourth year of education; (3) whether the beliefs of physical therapy students are related to their adherence to clinical guidelines in treating patients with LBP; and (4) whether beliefs and attitudes differ between physical therapy students with or without a personal history of LBP.

MethodsThe study procedures were in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2013. Ethics approval was acquired by an independent Commission of Medical Ethics linked to the University Hospital of Brussels, Brussels, Belgium. We followed the STROBE recommendations for the reporting of cross-sectional studies.20

ParticipantsSecond and fourth year physical therapy students of 6 Belgian universities - 4 Flemish and 2 Walloon - and 2 Dutch institutions were recruited. In Belgium, the physical therapy educational program consists of 5 years: 3 bachelors and 2 masters. In the Netherlands, the physical therapy educational program consists of 4 years to obtain a bachelor’s degree. Because the 1st year is traditionally characterized by a large drop-out of students, the 2nd year was chosen for inclusion. The 4th year was chosen because these students were close to graduation and this would allow us to compare students in both countries with similar number of education years.

Study designIn this cross-sectional study, a researcher collected the data from the students during the first semester of the 2014–2015 school year. Students signed an informed consent prior to participation. All students were told that the procedure was not an examination and that there were no ‘correct’ answers, but that they were free to express their actual thoughts and beliefs about LBP. A researcher was present to collect all completed forms, but no further information was given.

Outcome measuresAll questionnaires were validated in Dutch. For the Walloon universities, questionnaires were translated in French through a back and forth process by two translators based on the procedure described in literature.21 At the end, consensus was reached on the French versions.

One questionnaire addressed the student’s personal background (age, sex, personal history or presence of LBP). This was pilot-tested on a sample that comprised physical therapy students, non-medical students, and academic physical therapy staff who did not take part in the study (n=22). Minor format modifications were made based on this pilot data prior to administering the survey for the study. The other questionnaires that were used were the pain attitude and beliefs scale (PABS), the health care providers’ pain and impairment relationship scale (HC-PAIRS), and a vignette.

The PABS7,9 was developed to evaluate whether physical therapists have a biomedical or behavioral approach towards the management of patients with CLBP. The biomedical subscale (PABS-BIOM 10 items) had a satisfactory internal consistency, however the behavioral subscale (PABS-PS 9 items) showed poor internal consistency.9 After revision of the PABS in 2005, the internal consistency of the behavioral subscale improved (Crohnbach’s α 0.54 to 0.68). The items are scored on a six-point Likert scale. Therefore, the PABS-BIOM provides a minimum score of 10 and a maximum of 60, quantifying the biomedical view of the physical therapist. In addition, the PABS-PS provides a minimum score of 9 and a maximum of 54, quantifying the behavioral or psychosocial view of the physical therapist. The PABS's reliability and validity have been reported to be adequate. The PABS has been developed and tested in Dutch11 and used in past research with students.8

The HC-PAIRS,22 which originally consisted of 15 items, evaluates attitudes and beliefs of healthcare practitioners regarding functional expectations of patients with CLBP. Answers are marked on a seven-point Likert scale. The HC-PAIRS was modified (13 items) following a factor analysis on a sample of Dutch therapists and appears to be a reliable and valid measure.23 The minimum and maximum score on the HC-PAIRS is 13–91. Higher scores reflect stronger beliefs in the relationship between pain and impairment. This questionnaire has previously been used in a student population.8,13–15

A vignette10 is a clinical case scenario of a patient with LBP, providing information regarding symptoms, subjective evaluation, and medical history and results of clinical examination.10 The purpose was to evaluate treatment recommendations concerning activity restriction and work absenteeism. Rainville et al.20 developed 3 scenarios with different degrees of spinal pathology, symptoms, and work requirements, without any evidence of structural damage or neurological compression that would require surgery.20 In the present study, only the third vignette was used. This describes a factory foreman with persistent, severe back and leg pain after a motor vehicle accident and only minimal evidence of spinal degeneration on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Participants were asked to rate the patient’s ability to work and the need for activity restriction on a 5-point scale. The reliability of scoring the vignette was modest and internal consistency fair. It is difficult though to correctly determine the validity without a comparison with real patients.5 This vignette was translated in Dutch.23 Answers 1 (i.e. not limit any activities/work full time, full duty) or 2 (i.e. avoid only painful activities/work moderate duty, full time) in the vignette were defined as adequate recommendations for activity level (question 3) and work (question 4). This approach translated the answers into a dichotomous scoring system consistent or inconsistent with clinical guidelines,18 using the European guidelines for the management of LBP.1,2 In this way, the vignette gives an indication about the student’s attitudes.

Statistical analysisFor statistical analysis IBM SPSS Statistics 24 was used. Group normality was analyzed by Q/Q’-plots.24 Group equality was examined by an unpaired Student t-tests (PABS and HC-PAIRS) or chi-square tests (vignette) to answer the first, second, and fourth objective of the study. To enhance reliability, the total score on the HC-PAIRS or PABS subscales was excluded from analyses when 2 or more answers were missing. To answer the third objective, an unpaired Student t-test was performed to compare the average scores of the group with a guideline adherent attitude with the average scores of the group that had a guideline inconsistent attitude.

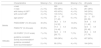

ResultsFour Flemish (University of Antwerp, Vrije Universiteit Brussel, University of Ghent, and Catholic University of Leuven), two Walloon (Université Catholique de Louvain and Université de Liège), and two Dutch institutes (Hanze University of Applied Sciences Groningen and University of Applied Sciences Rotterdam) agreed to participate. There were 929 second year and 695 fourth year students who participated for a total of 1624 participants. Among them, 46% of the participants experienced LBP at some point in their life, with 15% having LBP at the time of study participation. There was a significant difference between the two groups of students for age (95% confidence interval [CI]: −2.22, −1.82 years) and history of LBP, with more 4th year students having already experienced LBP during their lifetime (50% versus 43%, Table 1). No difference between groups was found in prevalence of LBP at the time of study participation (point prevalence).

Beliefs and attitudes of 2nd versus 4th year physical therapy students in Belgium and the Netherlands (n=1624).

| Characteristics | Missing n (%) | 2nd grade | Missing n (%) | 4th grade | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n total | – | 929 | – | 695 | |

| n male | 2 (<1%) | 353 (38%) | 4 (<1%) | 261 (38%) | |

| with history of LBP** | 5 (<1%) | 403 (43%) | 4 (<1%) | 345 (50%) | |

| with current LBP | 4 (<1%) | 133 (14%) | 3 (<1%) | 102 (15%) | |

| Beliefs | age (years)* | 4 (<1%) | 20±2.1 | 6 (<1%) | 22±2.0 |

| [17, 40] | [20, 39] | ||||

| PABS-BIOM* (10−60 scale) | 30 (3%) | 36.3±5.4 | 12 (2%) | 30.9±6.0 | |

| [14, 52] | [11, 46] | ||||

| PABS-PS* (9−54 scale) | 30 (3%) | 31.0±4.3 | 12 (2%) | 32.5±4.4 | |

| [14, 44] | [20, 48] | ||||

| HC-PAIRS* (13−91 scale) | 7 (<1%) | 52.8±7.8 | 7 (1%) | 46.4±8.5 | |

| [28, 77] | [17, 76] | ||||

| Attitudes | guideline consistent | 1 (<1%) | 329 (36%) | 4 (<1%) | 427 (62%) |

| activity recommendation* | |||||

| guideline consistent | 2 (<1%) | 90 (10%) | 4 (<1%) | 164 (24%) | |

| work recommendation* |

Data are mean±standard deviation, frequency (proportion) and range [min, max].

Legend: PABS, Pain attitudes and beliefs scale; BIOM, Biomedical subscale with higher scores reflecting a more biomedical belief; PS, psychosocial/behavioral subscale with higher scores reflecting a more (bio)psychosocial belief; HC-PAIRS, health care providers’ pain and impairment relationship scale with higher scores reflecting stronger beliefs in the relationship between pain and impairment; SD, standard deviation; min-max, minimum-maximum score.

Second year students scored significantly higher on the PABS-BIOM (mean difference [MD]=5.4, 95% CI: 4.79, 5.94) and on the HC-PAIRS (MD=6.4 points, 95% CI: 5.65, 7.28) compared to 4th year students. On the PABS-PS, 2nd year students scored significantly lower (MD=−1.5, 95% CI: −1.90, −1.02) (Table 1). When exploring the results for all institutions individually, the same trend was observed for all questionnaires, except for the PABS-PS in only one institution.

Table 2 provides an overview of all questionnaire items separately. On every item of the HC-PAIRS and PABS-BIOM, 2nd year students had a higher (or equal) mean and median score compared to 4th year students. On each item of the PABS-PS, except item 13 and 14, 2nd year students had a lower (or equal) mean and median score than 4th year students.

Scores on each item of the PABS and HC-PAIRS for 2nd and 4th year physical therapy students in Belgium and the Netherlands (n=1624).

| 2nd Year | 4th Year | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean±SD | Median | IQR | Mean±SD | Median | IQR | ||

| PABS-BIOM | 3 | 3.5±1.2 | 4 | [3,4] | 3.0±1.4 | 3 | [2,4] |

| 6 | 3.8±1.3 | 4 | [3,5] | 3.2±1.3 | 3 | [2,4] | |

| 8 | 2.8±1.1 | 3 | [2,4] | 2.3±1.1 | 2 | [2,3] | |

| 9 | 4.4±1.2 | 5 | [4,5] | 4.2±1.3 | 4 | [3,5] | |

| 10 | 3.6±1.0 | 4 | [3,4] | 3.3±1.1 | 3 | [2,4] | |

| 11 | 4.3±1.0 | 4 | [4,5] | 4.0±1.2 | 4 | [3,5] | |

| 12 | 3.5±1.1 | 4 | [3,4] | 2.6±1.1 | 2 | [2,3] | |

| 15 | 3.5±1.1 | 4 | [3,4] | 2.9±1.1 | 3 | [2,4] | |

| 16 | 3.2±1.2 | 3 | [2,4] | 2.2±1.0 | 2 | [1,3] | |

| 19 | 3.9±1.0 | 4 | [3,5] | 3.3±1.2 | 3 | [2,4] | |

| PABS-PS | 1 | 4.4±1.1 | 5 | [4,5] | 4.7±1.0 | 5 | [4,5] |

| 2 | 2.6±1.0 | 2 | [2,3] | 3.0±1.1 | 3 | [2,4] | |

| 4 | 3.8±1.3 | 4 | [3,5] | 4.4±1.1 | 4 | [4,5] | |

| 5 | 3.2±1.0 | 3 | [2,4] | 3.4±1.1 | 3 | [3,4] | |

| 7 | 3.0±1.2 | 3 | [2,4] | 3.3±1.3 | 3 | [2,3] | |

| 13 | 3.0±1.2 | 3 | [2,4] | 2.6±1.2 | 2 | [2,3] | |

| 14 | 2.9±1.0 | 3 | [2,4] | 2.7±1.0 | 3 | [2,3] | |

| 17 | 4.5±0.9 | 5 | [4,5] | 4.6±0.9 | 5 | [4,5] | |

| 18 | 3.8±1.3 | 4 | [3,5] | 4.0±1.2 | 4 | [3,5] | |

| HC-PAIRS | 1R | 4.2±1.3 | 4 | [3,5] | 4.0±1.3 | 4 | [3,5] |

| 2 | 4.3±1.4 | 4 | [3,5] | 3.4±1.4 | 3 | [2,4] | |

| 3 | 4.0±1.4 | 4 | [3,5] | 3.3±1.4 | 3 | [2,4] | |

| 4 | 4.0±1.6 | 4 | [3,5] | 3.9±1.6 | 4 | [3,5] | |

| 5 | 3.3±1.4 | 3 | [2,4] | 2.7±1.2 | 3 | [2,3] | |

| 6R | 4.8±1.3 | 5 | [4,6] | 4.7±1.3 | 5 | [4,6] | |

| 7 | 4.3±1.1 | 4 | [4,5] | 3.8±1.2 | 4 | [3,5] | |

| 8 | 4.5±1.5 | 5 | [3,6] | 3.6±1.6 | 3 | [2,5] | |

| 9 | 4.1±1.5 | 4 | [3,5] | 3.4±1.6 | 3 | [2,5] | |

| 10 | 4.3±1.4 | 4 | [3,5] | 3.6±1.5 | 4 | [2,5] | |

| 11 | 3.8±1.3 | 4 | [3,5] | 3.2±1.3 | 3 | [2,4] | |

| 12R | 4.1±1.2 | 4 | [3,5] | 4.0±1.3 | 4 | [3,5] | |

| 13 | 3.2±1.5 | 3 | [2,4] | 2.9±1.5 | 3 | [2,4] | |

Legend: PABS, Pain attitudes and beliefs scale; BIOM, Biomedical subscale with higher scores reflecting a more biomedical belief; PS, psychosocial/behavioral subscale with higher scores reflecting a more biopsychosocial belief; HC-PAIRS, health care providers' pain and impairment relationship scale with higher scores reflecting stronger beliefs in the relationship between pain and impairment; R depicts the reversed score; SD, standard deviation; IQR, interquartile range with [Q1, Q3].

On the questions about activity and work recommendations in the vignette, a significantly larger number of 4th year students made guideline consistent recommendations (respectively 62% and 24%) than 2nd year students (respectively 36% and 10%; p<.01). In total, only 16% of all students provided an answer consistent with the current guidelines on the question about work recommendation (Table 1). Looking at the raw scores, for the 2nd year students, the mean and median score for activity recommendation was 2.99 and 3.00 and for work absenteeism 3.53 and 4.00. For the 4th year students the mean and median score for activity recommendation was 2.47 and 2.00 and for work absenteeism 3.16 and 3.00.

Link between beliefs and attitudesTable 3 shows the relationship between the scores on the questionnaires (PABS and HC-PAIRS) and the answers on the last two questions of the vignette, i.e. concerning activity and work recommendation. In general, students who make recommendations consistent with the current guidelines have lower scores on the biomedical scales and a higher score on the PABS-PS.

Link between the beliefs and attitudes of 2nd and 4th year physical therapy students in Belgium and the Netherlands (n=1624).

| 2nd Year | 4th Year | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Guideline inconsistent | Guideline consistent | 95% Confidence interval | Mean difference | Guideline inconsistent | Guideline consistent | 95% Confidence interval | Mean difference | |

| Activity recommendation | ||||||||

| Age (years) | 20±1.9 | 20±2.4 | −0.39, 0.17 | −0.11 | 22±1.8 | 22±2.0 | −0.31, 0.29 | −0.01 |

| Male | 229 (38%) | 124 (38%) | 103 (39%) | 157 (37%) | ||||

| With current LBP | 85 (14%) | 48 (15%) | 39 (15%) | 62 (15%) | ||||

| With history of LBP | 250 (42%) | 153 (47%) | 124 (48%) | 219 (51%) | ||||

| PABS-BIOM | 36.6±5.5 | 35.6±5.3 | 0.31, 1.80 | 1.05 | 31.1±6.2 | 30.8±5.9 | −0.67, 1.21 | 0.27 |

| (10−60 scale) | ||||||||

| PABS-PS | 30.7±4.4 | 31.5±4.1 | −1.33, −0.15 | −0.74 | 31.9±4.6 | 32.8±4.3 | −1.57, −0.21 | −0.89 |

| (9−54 scale) | ||||||||

| HC-PAIRS | 53.6±7.5 | 51.5±8.1 | 1.06, 3.15 | 2.10 | 47.9±8.2 | 45.5±8.6 | 1.17, 3.78 | 2.48 |

| (13−91 scale) | ||||||||

| Work recommendation | ||||||||

| Age | 20±2.0 | 20±2.3 | −0.53, 0.38 | 22±1.8 | 22±2.3 | −0.71, 0.08 | ||

| Male | 314 (38%) | 39 (43%) | 197 (38%) | 62 (38%) | ||||

| With present LBP | 118 (14%) | 15 (17%) | 73 (14%) | 28 (17%) | ||||

| With history of LBP | 365 (44%) | 38 (42%) | 266 (51%) | 77 (47%) | ||||

| PABS-BIOM | 36.4±5.4 | 34.9±5.3 | 0.37, 2.76 | 1.56 | 31.4 ± 5.9 | 29.2 ± 6.0 | 1.14, 3.26 | 2.20 |

| (10−60 scale) | ||||||||

| PABS-PS | 30.9±4.3 | 32.2±4.4 | −2.29, −0.38 | −1.33 | 32.2 ± 4.4 | 33.4 ± 4.1 | −1.97, −0.41 | −1.19 |

| (9−54 scale) | ||||||||

| HC-PAIRS | 53.2±7.7 | 49.5±7.7 | 2.01, 5.38 | 3.69 | 47.2 ± 8.3 | 43.9 ± 8.7 | 1.78, 4.75 | 3.27 |

| (13−91 scale) | ||||||||

Data are mean±standard deviation and frequency (proportion).

Legend: PABS, Pain attitudes and beliefs scale; BIOM, Biomedical subscale with higher scores reflecting a more biomedical belief; PS, psychosocial/behavioral subscale with higher scores reflecting a more biopsychosocial belief; HC-PAIRS, health care providers’ pain and impairment relationship scale with higher scores reflecting stronger beliefs in the relationship between pain and impairment; min-max, minimum-maximum; LBP, low back pain.

Having a personal history of LBP or experiencing LBP at the time of study participation was not associated with different beliefs or attitudes (Table 4). For the second year students no significant differences were found in the characteristics of both groups (with/without LBP) based on sex or age. For the fourth year students no significant differences were found between the groups (with/without LBP) based on sex. However, a very small age difference was found (mean age of 22 in both “history of LBP” groups, mean age of 22 in the “no present LBP” group versus 21 in the “with present LBP”group).

Differences based on personal experience with LBP in the past or at study participation in the beliefs and attitudes of 2nd and 4th year physical therapy students in Belgium and the Netherlands (n=1624).

| HISTORY OF LBP | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2nd Year | 4th Year | |||||||

| No LBP | With LBP | Mean difference | 95% Confidence interval | No LBP | With LBP | Mean difference | 95% Confidence interval | |

| PABS-BIOM | 36.6±5.6 | 35.8±5.3 | 0.82 | 0.11, 1.54 | 30.9±6.3 | 30.9±5.8 | 0.06 | −0.85, 0.97 |

| PABS-PS | 31.0±4.4 | 31.1±4.2 | −0.14 | −0.71, 0.43 | 32.5±4.5 | 32.4±4.4 | 0.06 | −0.61, 0.72 |

| HC-PAIRS | 52. 9±7.8 | 52.7±7.8 | 0.27 | −0.75, 1.29 | 46.4±8.9 | 46.3±8.2 | 0.12 | −1.16, 1.41 |

| Guideline consistent activity recommendation | 175 (34%) | 153 (38%) | 208 (60%) | 219 (64%) | ||||

| Guideline consistent work recommendation | 52 (10%) | 38 (9%) | 87 (25%) | 77 (22%) | ||||

| PRESENT LBP | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PABS-BIOM | 36.3±5.5 | 35.9±5.3 | 0.42 | −0.60, 1.43 | 31.0±6.2 | 30.5±5.4 | 0.52 | −0.76, 1.80 |

| PABS-PS | 30.9±4.4 | 31.3±4.1 | −0.38 | −1.19, 0.42 | 32.4±4.4 | 32.7±4.4 | −0.30 | −1.23, 0.63 |

| HC-PAIRS | 52.9±7.8 | 52.4±7.7 | 0.45 | −0.98, 1.89 | 46.6±8.5 | 45.1±8.6 | 1.50 | −0.30, 3.30 |

| Guideline consistent activity recommendation | 280 (35%) | 48 (36%) | 365 (62%) | 62 (61%) | ||||

| Guideline consistent work recommendation | 75 (10%) | 15 (11%) | 136 (23%) | 28 (28%) | ||||

Data are mean±standard deviation and frequency (proportion). Legend: LBP=low back pain, PABS=Pain attitudes and beliefs scale, BIOM=Biomedical subscale with higher scores reflecting a more biomedical belief, PS=psychosocial/behavioral subscale with higher scores reflecting a more (bio)psychosocial belief, HC-PAIRS=health care providers’ pain and impairment relationship scale with higher scores reflecting stronger beliefs in the relationship between pain and impairment.

No significant differences existed between the two groups regarding PABS and HC-PAIRS scores, except for one item. In general, 2nd year students who never experienced LBP in their life seem to score slightly higher on the PABS-BIOM compared to 2nd second year students who already experienced LBP (p<.05). No significant difference was found in their recommendations.

DiscussionThe general findings of the current study are: (1) only 47% of the physical therapy students provide clinical guidelines’ consistent recommendations for activity and only 16% for work; (2) compared to 4th year students, 2nd year physical therapy students score higher on biomedical subscales and lower on the psychosocial subscale; the former group makes more guideline consistent recommendations about work and activity compared to the latter; (3) students with a greater biopsychosocial belief regarding LBP, compared to a stronger biomedical belief, give recommendations that are more consistent with current guidelines; and (4) personal experience with LBP is not associated with different beliefs or attitudes.

BeliefsCompared to 2nd year students, 4th year students have more biopsychosocial beliefs regarding LBP. This conclusion applies to the overall group as well as to all participating institutions. While the present cross-sectional design does not allow to identify a causal relationship, it can be concluded that the biopsychosocial perspective is more present in the final years of the educational program. These results confirm findings by Ryan et al. indicating that 4th year physical therapy students in Scotland had less biomedical beliefs towards patients with back pain in comparison to first year students.25 These findings, as well as those from another study conducted by Morris et al., show the same phenomenon in non-medical students, which challenges the idea that a change in attitudes could be explained by healthcare education.15 However, in that study the change in beliefs from the 1st to the 4th year is considerably greater in physical therapy students compared to non-medical students.25 This strengthens the assumption that the healthcare-related curriculum contributes to students’ further development of biopsychosocial beliefs.

In the Dutch population, people generally have biomedical beliefs about LBP.26 There was a difference in the focus of the biomedical thinking between people with or without CLBP, but in the end, the general population fails to see the influence of for example psychological issues. In the current study, this biomedical belief was reflected in the 2nd year students. For the different institutions, it might be interesting to take these initial beliefs into account when (re)constructing the curriculum.

Unfortunately, there are no cut-off points available for these questionnaires that indicate a high or a low score, nor has the minimal clinically important difference been determined. This makes it difficult to interpret the differences found in terms of clinical relevance. However, looking at the differences in biomedical scores between the 2nd and 4th year, a difference of 5.4 on a scale of 50 points (PABS-BIOM) and 6.4 on a maximal scale of 78 (HC-PAIRS) may be important. This means a difference in biomedical perspective of approximately 10% between the 2nd and 4th year. The clinical relevance in psychosocial scores is probably more debatable with only slightly more than a 3% difference between the 2nd and 4th year.

AttitudesAlongside the beliefs, the overall attitude of 4th year students is also more in line with current guidelines compared to 2nd year students. From the latter group, 36% of the students make guideline consistent recommendations about activity and only 10% about work. However, guideline adherence is relatively low in all students. Less than half of the students (47%) follow the guidelines concerning activity recommendations and only 16% answer according to the guidelines concerning work absenteeism. This means that 84% of all students would advise this patient to stay (partially) at home or to limit his job only to light loads. There can be numerous reasons why guideline adherence is so low. A possibility is that the educational curriculum still has a strong biomedical focus. The need for physical activity and activation is perhaps more present in the curriculum than the focus on consequences such as work. In Belgium, physical therapy is on referral by a physician, in contrast to the Netherlands where patients have direct access. Especially in Belgium, the physician is the only qualified person to prescribe work absenteeism. Beliefs and attitudes are not learned intentionally, so the indirect message of an educational program can influence someone’s attitudes and beliefs. Previous research among 2nd year physical therapy students showed that relatively short biopsychosocial training sessions can positively influence attitudes and beliefs.18 This intervention showed a significant shift to more guideline consistent recommendations. However, in the present study eight independent institutions were included to minimize any bias of a single educational track. Traditionally, education is still mainly about teaching new knowledge and less about reflecting on student’s current knowledge and reframing those thoughts. Perhaps we lack a step in the curriculum to translate the student’s biopsychosocial beliefs into interventions. Further research will be necessary to identify possible causes of this non-adherence and to tackle these barriers during the educational curriculum.

The findings that work recommendations are less consistent with guidelines compared to activity recommendations is consistent with previous research.18 The mean scores for the 2nd year physical therapy students in the study by Domenech et al. are comparable to the scores in the present study (activity recommendation respectively 2.77 compared to 2.99, work absenteeism 3.37 compared to 3.53).18 A possible explanation can lie in the doctor-patient relationship which is perceived to be in jeopardy when making decisions regarding sick leave.27 Further research is necessary to identify the low guideline adherence towards both recommendations.

Link between beliefs and attitudesStudents who make guideline-consistent recommendations based on the vignette have lower HC-PAIRS scores, higher PABS-PS scores, and lower PABS-BIOM scores (except the 4th year students). This implies that students with a biopsychosocial orientation adhere more to the current clinical guidelines concerning work and activity levels of patients with LBP. These findings are in line with initial expectations that a person’s beliefs influence one’s behavior 6 and with the existing evidence provided by previous studies conducted on students and general practitioners in other countries.18,28

Relationship with personal history of LBPHaving a personal history of LBP, currently or in the past, did not relate to changes in students’ attitudes or beliefs, which is in accordance with previous research findings.13–15,18,29 This is somewhat surprising given the fact that the CSM states that perceptions are based on former experiences.6 Perhaps this partially questions the theory by Leventhal et al. or perhaps a healthcare practitioner can empathize in different roles, where the perceptions of the person as a physical therapist (being the job) are separated by the perceptions of the person as a patient. One reason can be that the level of LBP or the impact it had on their life was minimal, since no cut-off was used. All students who answered positive on the question about LBP, where classified as having personal experience with LBP, regardless of the pain score, the duration, or the impact. Further research should explore this in more detail.

Study limitations and strengthsParticipants of the current study were only provided one vignette. Additional vignettes would provide more and stronger data. However, given the fact that the study already included several questionnaires, expansion could lead to data loss with decreasing concentration.

The questions accompanying the vignette had five possible answers, however for the purpose of the current study, answers were treated dichotomously. Furthermore, questionnaires and a vignette remain fictional. Future research should compare the current results with the observation during real life situations to evaluate actual clinical behavior, because the validity between vignettes and real life situations can be questioned.30

The study also had several strengths. These include the large sample size (n=1624), the large number of institutions involved (n=8), the international and multilingual setting, the use of tools that generate reliable and valid data, and the large participation rate among the students.

This study had a cross sectional design so no causal relationships can be drawn. To investigate the long term effect of education on the future approach of these physical therapy students, further research should include a longitudinal design with more information about educational factors of the curriculum.

ConclusionA positive shift occurs from a merely biomedical model towards a more biopsychosocial model from the 2nd to the 4th year of physical therapy education. However, guideline adherence concerning activity and work recommendations remains low among physical therapy students. As expected, there is a link between beliefs and attitudes. Previous experience with LBP however, did not have a significant impact on the beliefs or attitudes.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.

The author wishes to thank all institutions involved for their participation.