Bladder training (BT), the maintenance of a scheduled voiding regime at gradually adjusted intervals, is a common treatment for overactive bladder (OAB).

ObjectivesTo assess the effects of isolated BT and/or in combination with other therapies on OAB symptoms.

MethodsA systematic review of eight databases was conducted. After screening titles and abstracts, full texts were retrieved. Cochrane RoB 2 and the GRADE approach were used.

ResultsFourteen RCTs were included: they studied isolated BT (n = 11), BT plus drug treatment (DT; n = 5), BT plus intravaginal electrical stimulation (IVES; n = 2), BT plus biofeedback and IVES (n = 1), BT plus pelvic floor muscle training and behavioral therapy (n = 2), BT plus percutaneous tibial nerve stimulation, and BT plus transcutaneous tibial nerve stimulation (n = 1). In a meta-analysis of short-term follow-up data, BT plus IVES resulted in greater improvement in nocturia (mean difference [MD]: 0.89, 95% CI: 0.5, 1.20), urinary incontinence (UI; MD: 1.93, 95% CI: 1.32, 2.55), and quality of life (QoL; MD: 4.87, 95% CI: 2.24, 7.50) than isolated BT, while DT and BT improved UI (MD: 0.58, 95% CI: 0.23, 0.92) more than isolated BT.

ConclusionIn the short term, BT plus IVES improves the OAB symptoms of nocturia and UI while improving QoL. The limited number of RCTs and heterogeneity among them provide a low level of evidence, making the effect of BT on OAB inconclusive, which suggests that new RCTs should be performed.

According to the International Continence Society, overactive bladder (OAB) is characterized by symptoms of urinary urgency with or without urgency urinary incontinence but usually accompanied by frequency and nocturia in the absence of urinary tract infections or other detectable diseases.1–3 OAB symptoms are associated with significant costs and adversely affect quality of life (QoL). They can impact interpersonal relationships, sleep, and the mental and physical health of individuals affected.1,4–8

Estimates of the prevalence of OAB in the general population are highly variable (2%–53%).4–17 The literature indicates a prevalence of approximately 35% in males and 41% in females. These rates increase with age in both sexes.4,9–19 The prevalence in the female population is higher,9–11 perhaps due to certain phenotypes, such as those identified by Peyronnet et al.20 This highlights the importance of individualizing treatments.

The American Urological Association and the Society of Urodynamics, Female Pelvic Medicine, and Urogenital Reconstruction (AUA/SUFU) recommend behavioral therapy, such as bladder training (BT), as the first-line treatment approach. Drug treatment (DT) is the recommended second line, while the third line comprises various modalities of peripheral electrical stimulation, such as intravaginal electrical stimulation (IVES), percutaneous tibial nerve stimulation (PTNS), transcutaneous tibial nerve stimulation (TTNS), sacral neuromodulation, and intradetrusor injection of onabotulinum toxin A.21

Behavioral therapy comprises a group of therapeutic strategies designed to improve OAB symptoms by modifying the patient's daily habits, lifestyle, and environment.21 Behavioral therapy programs apply scheduled voiding regimes, pelvic floor muscle training (PFMT), and lifestyle changes.21,22 Scheduled voiding regimes have been used for decades to manage OAB symptoms. These protocols have been divided into BT, timed voiding, habit training, and prompted voiding.21,22 The difference between them lies in how the scheduled voiding is modified and whether the patient's involvement is active or passive.21,22

BT uses several approaches to help individuals delay voiding. The main approach is activities that require mental focus, such as relaxation and distraction techniques. These activities are often accompanied by repetitive contractions of the pelvic floor muscles (PFM), which stimulate an inhibitory detrusor reflex.21–24 While delaying voiding, voluntary contractions of the PFM activate afferent stimulation through the pudendal nerve to the sacral voiding center, which in turn elicits inhibitory responses in the detrusor via the pelvic nerve (the perineodetrusor inhibitory reflex), resulting in delayed voiding intervals.21,25

The advantages of BT include its low cost, low complexity, and lower risk of adverse events (AE). The last systematic review on the efficacy of BT for urinary incontinence (UI), conducted in 2004, recommended further investigation because protocols were very heterogeneous.26 The aim of the present review was to investigate whether BT—either in isolation or in combination with other therapies—can promote improvement in OAB symptoms (primary outcomes), QoL, and reported AE (secondary outcomes).

MethodsSearch methods for identifying studiesSearches were conducted in the following electronic databases: PubMed Central/MEDLINE, PEDro, SciELO, LILACS, Cochrane Central Library, Web of Science, EMBASE, and CINAHL. There were no restrictions on the year of publication or language (Also see Supplementary material online 1). Two authors independently reviewed the titles, abstracts, and full texts of all identified studies. Disagreements between reviewers were resolved by consensus or mediation by a third author.

Selection of studiesThis systematic review was prospectively registered in the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO; CRD:42022301522), prepared according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA), and conducted according to the Cochrane methodology for randomized clinical trials (RCTs).27,28

Eligibility criteriaDuring the search, no language or date filters were used. After the search, we included RCTs written in English in which BT was compared to various therapies, such as DT, IVES, PFMT, a control group (CG), PTNS, TTNS, behavioral therapy, and biofeedback, in terms of their capacity to reduce OAB symptoms.

The outcome measures for this review were OAB symptoms, QoL, and/or reported AE. The primary outcomes (urinary urgency and frequency, nocturia, and/or urgency urinary incontinence) were assessed by tools such as bladder diaries and/or 24-hour pad tests. QoL was assessed by tools that assess QoL. AE tools were reported by tool or by the study.

The population of interest was women and men over 18 years of age. Studies concerned with neurologic and psychiatric disorders, peri&#¿; and post-operative periods, or pregnant women, postpartum women, and community-dwelling individuals were excluded. Only fully published RCTs were included in the review. However, studies with participants who had received prior treatment for OAB symptoms were excluded.

Data extraction and managementSearches were conducted independently by two authors from December 2021 to July 2022. The results of the database searches were imported into the software program Mendeley Reference Management 2.67.0 and finalized using EndNote X9 software.29,30 In each search process, two reviewers assessed the studies collected in the databases in the order of title, abstract, and full text. RCTs eligible for inclusion in the review were selected for full read throughs. The screening results were saved, documented, and presented in a flowchart, as recommended by the PRISMA Statement.27

After the studies were selected, AKLR and DVP determined the selection and inclusion of outcome measures in the review. The following data were extracted: title, author, year, country, number of participants, sexes, primary and secondary outcomes, aims, interventions in each group, program details, duration of sessions, frequency and duration of interventions, and outcomes at baseline and follow-up assessments. The intervention of primary interest was BT's effect in isolation or in combination with other treatments on OAB symptoms. The outcomes at baseline, at the first post-treatment assessment, and after a second post-treatment assessment, when possible, were subjected to comparison and meta-analysis. Comparisons were made between equivalent RCTs. The extraction of these outcome measures and other characteristics of the RCTs was conducted by MPV, and a third reviewer was consulted. When discrepant data were noted, an email was sent to the authors of the studies under analysis.

Data analysis and synthesisRisk of bias assessmentThe quality of the included studies was assessed using the risk of bias tool for RCTs, version 2 (RoB 2), from the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions.28 The OAB symptoms in the RCTs were assessed by two reviewers (AKLR and MPV). The assessments yielded ratings of either a “low” or “high” risk of bias, or “some concerns”. Any disputes between the reviewers were resolved through discussion or arbitration with a third author.

Measures of treatment effectsThe meta-analysis in this systematic review relied on data from all RCTs included for potential comparisons and on the identified outcomes of interest. The meta-analysis proceeded only when multiple studies assessed the same outcome, in which case we calculated the mean difference (MD) with a 95% confidence interval (CI) for continuous variables using means and standard deviations (SD).28–35 For analyses across studies, 95% confidence intervals and two-sided p values were used for each outcome. Review Manager 5.4 (RevMan) software was used for all analyses and meta-analyses.28,31,32

To test for heterogeneity between studies, effect measures were assessed using both the X2 test and the I² statistic.33 Therefore, an I² value greater than 50% was considered to indicate satisfactory heterogeneity.34 A funnel plot was used to examine the dispersion of the estimated effects of the intervention assessed in each RCT relative to a measure of the size or precision of each study.35

Quality of evidenceOverall effectiveness and improvement of OAB symptoms were evaluated using the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) approach. This approach assesses various factors, such as study limitations, inconsistencies, indirect evidence, imprecision, and publication errors and biases, to determine the level of evidence provided by the reviewed studies. The levels of evidence assigned by the GRADE approach include “high,” “moderate,” “low,” and “very low,” indicating the strength and quality of the evidence presented.36,37

Changes to the protocolThe protocol registered with PROSPERO included characteristics of the initial studies. Some items were updated, such as measures of treatment effects and outcomes.

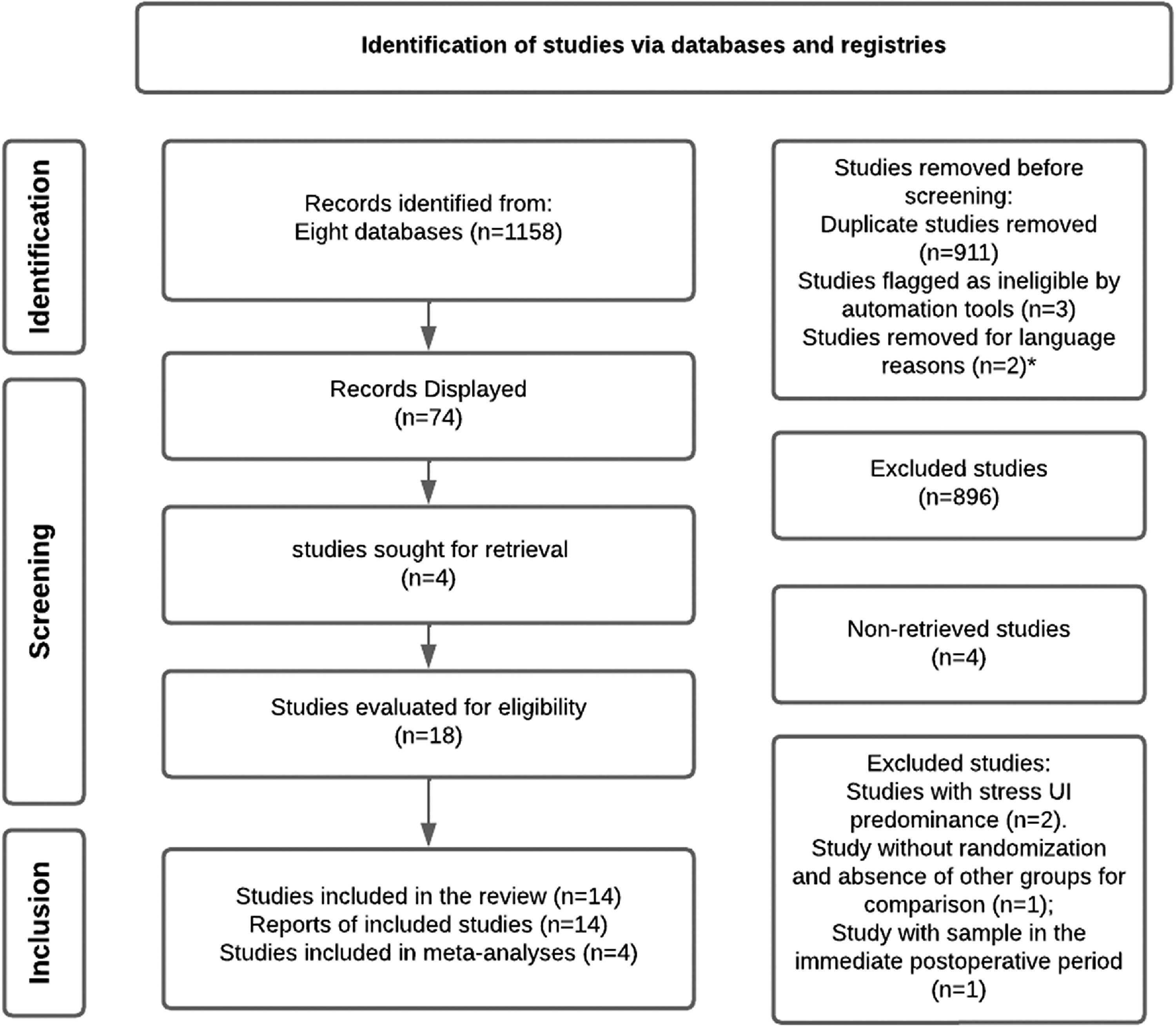

ResultsThe search yielded a total of 1158 studies. After applying the inclusion criteria, 14 studies were included in the review, but only 4 RCTs were appropriate for meta-analysis. A total of 896 studies were excluded. Some RCTs were presented in other languages and excluded for this reason (Fig. 1).

Flow chart of studies selection process in accordance with PRISMA guidelines.

The RCTs included 2319 18 to 80-year-old participants of both sexes and were conducted in 9 countries. The studies reported a higher female population, with a total of 1632 women.38–51 The sample sizes varied between 48 and 643 participants (mean =165.57, SD =179.05). Only two RCTs had samples that consisted of both women and men, as reported in Table 138,39 (Also see Supplementary material online 2).

Presents the characteristics of the 14 selected studies.

| Author/ year (country) | Sample size (n) | Mean Age SD (y) | Women/Men (W/M) | Outcome measure | Aims | Interventions in each group and program details | Duration of session | Frequency | Duration of intervention |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fantl 199140 (United States of America) | Total: 131BT: 60CG: 63 | BT: 66 (SD 8)yCG: 68 (SD 9)y. | Women | Bladder diary (1-week) - number of UI episodes, nocturia.Cure. | To assess the efficacy of BT in women with UI. | Arms: 2.Interventions:CG vs BT.BT protocol: Voiding intervals were scheduled every 30 to 60 min based on a patient's baseline daytime voiding interval. The interval was then gradually increased by 30 min each week, with the program's goal being to achieve a voiding interval of 2.5 to 3 h. | 15 to 20 min. | 6 X week. | 6 weeks. |

| Colombo 199541 (Italy) | Total: 81BT: 39DT: 42 | BT: 49 (range 24–65)yDT: 48 (range 31–65)y. | Women | Bladder diary:(1-week): nocturia, frequency, UI.Cure.AE. | To compare the effects of six weeks of treatment withBT or DT for UI. | Arms: 2.Interventions: BT vs DT.BT Protocol: At program onset, we established the maximum time lapse between two voiding events and instructed participants to delay their initial voiding until 30 min beyond this identified interval. Then, women are instructed to increase this interval by 30 min every 4 or 5 days. The objective is to increase the delay between voidings up to 3 or 4 h. | – | BT: not reported.DT: Oxybutynin 5 mg daily. | 6 months. |

| Mattiasson 200338 (United States of America) | Total: 505CT (BT + DT): 244DT: 257 | CT (BT + DT): 62 (range 19–86)yDT: 63 (range 22–86)y | Men and women | 3-day bladder diary:urgency, frequency and UI. Volume voided per voiding, and urinary urgency episodes/24 h.Patients' perception of the severity.AE. | To compare the efficacy of BT + DT with DT isolated in participants with OAB. | Arms: 2Interventions: CT (BT + DT) vs DT.CT (BT + DT) protocol: The participants received a daily dose of tolterodine at 2 mg, which could be reduced to 1 mg in the first 2 weeks. Additionally, they received a concise overview of their health status, and instructions on how to manage their medication and maintain proper fluid intake throughout the study. | – | BT: not reported.DT and CT: Tolterodine2 mg/2 daily- 1 mg −1 mg/2 daily during the first 2 weeks. | 24 weeks. |

| Song 200642(Seoul/ Korea) | Total: 139BT: 26DT: 36CT (BT + DT): 31 | BT: 45.73 (SD 12.68)yDT: 48.41 (SD 9.38)yCT (BT + DT): 45.42 (SD 9.54)y. | Women | Bladder diary: Urinary urgency, frequency and nocturia.Patients’ subjective assessment of their bladder condition.AE. | To determine the optimal initial treatment approach for OAB.. | Arms: 3.Interventions: BT vs DT vs CT (BT + DT).BT Protocol: Participants were directed to review their bladder diary to determine their maximum interval for voiding and sustaining urinary urgency. They were then instructed to gradually increase this interval by 15-minute increments with the goal of achieving a 3–4 hour interval and a voided volume of 300–400 ml. In the event of urinary urgency, participants were taught to perform Kegel exercises. | – | BT: not reported.CT and DT: Tolterodine 2X per day. | 24 weeks. |

| Kim 200843 (Korea) | Total: 48BT: 23CT (BT + DT): 25 | BT: 58.0 (range 60.0, 67.0)yCT (BT + DT): 59.0 (range 51.0, 65.5)y. | Women | 3-day bladder diary: frequency.Uroflowmetry: post-void residual urine volume measurement.Subjective satisfaction. | To assess the impact of BT or its combination with DT on women with frequency for a duration of three months. | Arms: 2.Interventions:BT vs CT (BT + DT).BT protocol: Participants were educated on BT by one of the authors who taught them about the anatomy of the lower urinary tract. The author provided instructions on how to perform BT to increase the voiding interval by 30 min, with a goal of achieving 3–4 h and a voided volume of 300–400 mL. Participants were also instructed to perform Kegel exercises. | – | BT: not reported.CT: Propiverine 20 mg daily. | 3 months. |

| Lauti 200844 (New Zeland) | Total: 57BT: 21DT: 16C (BT + DT): 19 | BT: 53.8 (SD 14.8)yDT: 63.9 (SD 17.2)yCT (BT + DT): 47.6(SD 16.3)y. | Women | 3-day bladder diary: urinary urgency, frequency, nocturia and UI.OAB-q total HRQL score.SF-12.ICIQ-SF.AE. | To assess the clinical effectiveness of BT, DT, and CT in treating OAB in women. | Arms: 3.Interventions: BT vs DT vs CT (BT + DT).BT protocol: Physical therapy is performed for each participant in an individualized manner, using a bladder diary. Participants receive orientation on the anatomy and function of a "normal" bladder, as well as lifestyle habits that impact continence. Urinary urgency strategies include voluntary contraction of PFM to delay urgency. | – | BT: not reported.DT: Oxybutynin was initiated at a starting dosage of 2.5 mg per day.Subsequently, the dosage was gradually increased by 2.5 mg every 5 days. | 12 months. |

| Mattiasson 200939(United Kingdom) | 643DT: 323CT (BT + DT): 320 | DT: 58.2 (range 20–87)yCT (BT + DT): 58.6 (range 18–85)y. | Men and Women | 3-day bladder diary: urgency and frequency.Number of pads used.Percentage of participants requiring an increase in dose at 8 weeks.Perception of Bladder condition.Treatment Satisfaction (VAS)I-QoL total score.AE. | To compare the effectiveness of DT with and without simplified BT in participants diagnosed with OAB. | Arms: 2.Interventions: CT (BT + DT) vs DT.CT (BT + DT) protocol: Participants wrote in their diaries where they record their bathroom visits and episodes of incontinence. PFM requires contraction to prevent the sensation and alleviate episodes of UI. They can gradually increase the time between visits to the bathroom in order to pass urine while gradually extending this time to between voiding.PFM requires contraction of the rectal muscles for men, and the vaginal muscles for women, to prevent the sensation and alleviate episodes of UI. The participant should attempt to exercise mental control over their bladder and disregard the urgency to urinate. | – | CT and DT: 1X per day (Solifenacin 5 mg) or (Solifenacin 5/10 mg). | 16 weeks. |

| Kafri 201445 (Israel) | Total: 164DT: 42BT: 41CT (BT + PFMT + behavior therapy): 41PFMT: 40 | BT: 57.2 (SD 8.2)yCT (BT + PFMT + behavior therapy): 56.2 (SD 7.8)yDT: 57.1 (SD 9)yPFMT: 56.4 (SD 7.1)y | Women | 24-h Bladder diary: frequency and UI.I-QOL.VAS.ISI.Number of pads/weekSelf-reported Late-Life Function and Disability Instrument (LLFDI).AE. | To compare the long-term effectiveness of BT, PFMT, DT and DT in participants with UI. | Arms: 4.Interventions: BT vs DT (tolterodine) vs PFMT vs CT (BT + PFMT + behavior therapy).BT and CT protocol: Increasing the duration between voiding can be achieved by the participant. BT comprises of three components: (i) educating patients about bladder function and continence; (ii) directing patients to schedule voiding using a pre-set or flexible plan to extend the duration between voiding - aiming for a 3–4 h interval; and (iii) providing psychological support and encouragement as positive reinforcement. | – | BT, CT, PFMT: not reported.DT: tolterodine SR 4 mg but not reported frequency. | 12 months. |

| Azuri 201746 (Israel) | Total: 120BT: 41DT: 42PFMT: 40CT (BT + PFMT + behavior therapy): 41 | BT: 63 (iqr 52–68)yDT: 58 (iqr 51–68)yPFMT: 59 (iqr 54.5–64.5)yCT (BT + PFMT + behavior therapy): 58 (iqr 54–67)y | Women | Bladder diary: frequency and UI.Number of voids/24 h, number of UI/week.Dry rate at 4 years.AE. | Evaluate the four-year outcomes of three distinct protocols for pelvic floor physical therapy and DT in individuals with UI and OAB. | Arms: 3Interventions:BT vs DT (Tolterodine) vs PFMT vs CT (BT + PFMT + behavior therapy).BT protocol: The program aims to improve continence through three interventions: (i) educating participants on bladder function and usual continence maintenance practices, (ii) gradually increasing the intervals between voidings, and (iii) providing psychological support and encouragement for positive reinforcement.. | – | 4 sessions, occurring once every three weeks. | 4 years. |

| Hulbaek 201651 (Denmark) | Total: 91Individual BT: 43Group BT: 48 | Individual BT: 57.4 (SD 13.8)yGroup BT: 57.7 (SD 15.1)y. | Women | Bladder diary:Urinary urgency episodes/day,UI/ day,Voidings/day.VAS score bother, voiding;VAS score bother, nocturia.VAS score bother, urinary urgency;VAS score bother, UI.PGI-I.AE. | To compare the effectiveness of an individual BT program vs a group BTy program for participants with OAB. | Arms: 2.Interventions: individual BT vs group BT.BT protocol: Daily for two months, including patient education, coaching of the participant's scheduled voiding pattern through the bladder diary, and motivation for behavioral changes. | – | Daily. | 2 months. |

| Rivzi 201849(Pakistan) | Total: 147BT: 47PFMT: 50PFMT + BF: 50 | BT: 55.7 (SD 14.7)yPFMT: 49.1 (SD 14.9)yPFMT + BF: 49.3 (SD 14.7)y | Women | Bladder diary: urinary urgency, frequency and UI.UDI-SF6.IIQ-SF7.AE. | To compare the effectiveness of BT, PFMT, and PFMT + BF in treating OAB. | Arms: 3.Interventions: BT vs PFMT vs PFMT+ BF.BT Protocol: Techniques used to suppress urinary urgency include self-monitoring through the use of bladder or voiding diaries, lifestyle modifications, such as eliminating bladder irritants from the diet, managing fluid intake, weight control, bowel regulation, and smoking cessation, as well as time voiding. Fluid intake was evaluated using a bladder diary. The BT session lasted approximately 20 min during the initial visit and was reinforced in subsequent visits. Participants were instructed to postpone voiding until they achieved a specific goal, typically around 1–2 h initially. Once the required interval was reached without causing discomfort, they were advised to increase the interval by approximately 30 min over a 2-week period. | BT: 20 min.PFMT: not reported.PFMT + BF: not reported. | BT: increasing by 30 min within 2 weeks,PFMT: 3X per day.PFMT + BF: 2X per week. | 12 weeks. |

| Firinci 202047 (Turkey) | Total: 70BT: 18CT (BT + BF): 17CT (BT + IVES):18CT (BT + BF + IVES): 17 | BT: 54.88 (SD 11.01)CT (BT + BF): 52.62 (SD 11.83)yCT (BT + IVES): 58.52 (SD 10.24)yCT (BT + BF + IVES): 57.06 (SD 11.54) | Women | 3‐day-bladder-diary:frequency, nocturia and UI.24‐h pad test.IIQ-7.AE. | To assess the effectiveness of BT vs CT (BT + BF) vs CT(BT + IVES) vs CT (BT + BF + IVES) and the clinical parameters in OAB. | Arms: 4.Interventions: BT vs CT (BT + BF) vs CT (BT + IVES) vs CT (BT + BF + IVES).BT Protocol: The protocol consists of four stages: (1) Women were introduced to the location of the PFM, pelvic anatomy, and pathophysiology, all of which were explained by their physician during their visit. (2) They learned about urinary urgency suppression strategies. (3) A timed voiding program was initiated. (4) Continued BT was implemented. | BT: 20 min.IVES: 20 min. | 3 days for week (24 sessions). | 8 weeks. |

| Yildiz 202148(Turkey) | Total: 62BT: 31CT (BT + IVES): 31 | BT: 56.44 (SD 11.62)yCT (BT + IVES): 55.24 (SD 10.57)y. | Women | 3-day bladder diary: frequency, nocturia and UI.24-h pad test.Number of pads.OAB-V8.IIQ-7.Treatment success (positive response rate).AE. | To assess the effectiveness of adding IVES to BT in improving clinical parameters and QoL in patients with OAB. | Arms: 2Intervention: BT vs CT (BT + IVES)BT Protocol: Participants were informed about BT, which consists of four stages lasting 30 min each. They were then provided with a written brochure to complete the program at home. In the second stage, strategies to suppress urinary urgency were included, with the goal of delaying voiding, inhibiting detrusor contraction, and preventing urinary urgency. During the final stage, participants were encouraged to continue using the BT techniques. | BT: 20 min.IVES: 20 min. | 3 days for week (24 sessions). | 8 weeks. |

| Sonmez 202150(Turkey) | Total: 60BT: 19CT (BT + PTNS): 19CT (BT + TTNS): 20 | BT: 54.63 (SD 11.77)yCT (BT + PTNS): 57.31 (SD 14.80)yCT (BT + TTNS): 62.15 (SD 10.94)y. | Women | 24-h pad test.3-day bladder diary:frequency, nocturia and UI.Number of pads.OAB-V8.IIQ-7.Treatment success.Treatment satisfaction.Level of discomfort of application (VAS).AE. | To compare the effectiveness of PTNS and TTNS when added to BT in treating OAB. | Arms: 3.Interventions: BT vs CT (BT + PTNS) vs CT (BT + TTNS)BT protocol: Participants were introduced to the location of the pelvic floor muscles and the anatomy and pathophysiology of the pelvic region. In the second phase, strategies for suppressing urinary urgency were implemented with the goal of delaying voiding, inhibiting detrusor contraction, and preventing urinary urgency. | BT: 30 min.PTNS and TTNS: 30 min. | 2 days per week (12 sessions). | 6 weeks. |

Short-term follow-up = up to 3 months; medium-term follow-up = from 3 months to 12 months; long-term follow-up= over 12 months. Abbreviations: AE: Adverse event; 24 h pad test; 3-day bladder diary or 3-day-voiding-diary: 3 day voiding diary; BF: Biofeedback; BT: Bladder training; CG: Control Group; CT: Combination Therapy; DI: Detrusor instability; DT: Drug Treatment; h: hour; ICIQ-SF: International Consultation on Incontinence Questionnaire - Short Form; IIQ-SF7 or IIQ-7: Incontinence Impact Questionnaire Short-form 7; I-QoL: Incontinence Quality of Life Questionnaire; iqr: interquartile range; ISI: Incontinence Severity Index; IVES: Intravaginal electrical stimulation; mg: milligrams; ml: millilitres; OAB: Overactive bladder; OAB-q total HRQL score: International Consultation on Incontinence Questionnaire Overactive Bladder Quality of Life Module; OAB-V8: Overactive Bladder Questionnaire; PFM: Pelvic Floor Muscle; PFMT: Pelvic Floor Muscle Training; PTNS: Percutaneous tibial nerve stimulation; QoL: Quality of life; SD: Standard Deviation; SF-12 Questionnaire: SF-12 Generic Questionnaire of Quality of life; SI: Sphincter incompetence; TTNS: Transcutaneous tibial nerve stimulation; UDI-SF6: Urogenital Distress Inventory Short-form 6; UI: Urinary Incontinence; VAS: Visual Analog Scale; y: year.

The interventions applied in the RCTs involved comparing a variety of therapeutic approaches to BT. One study established a control group (CG),40 while eight integrated DT into the interventions.38,39,41–46 Two RCTs used IVES,47,48 and two studies mentioned biofeedback as part of the intervention.47,49 One RCT included both TTNS and PTNS.50 Three RCTs integrated PFMT.45,46,49 Two studies recommended behavioral therapy.46,47 One study compared two different ways of offering BT: in a group and individually.51

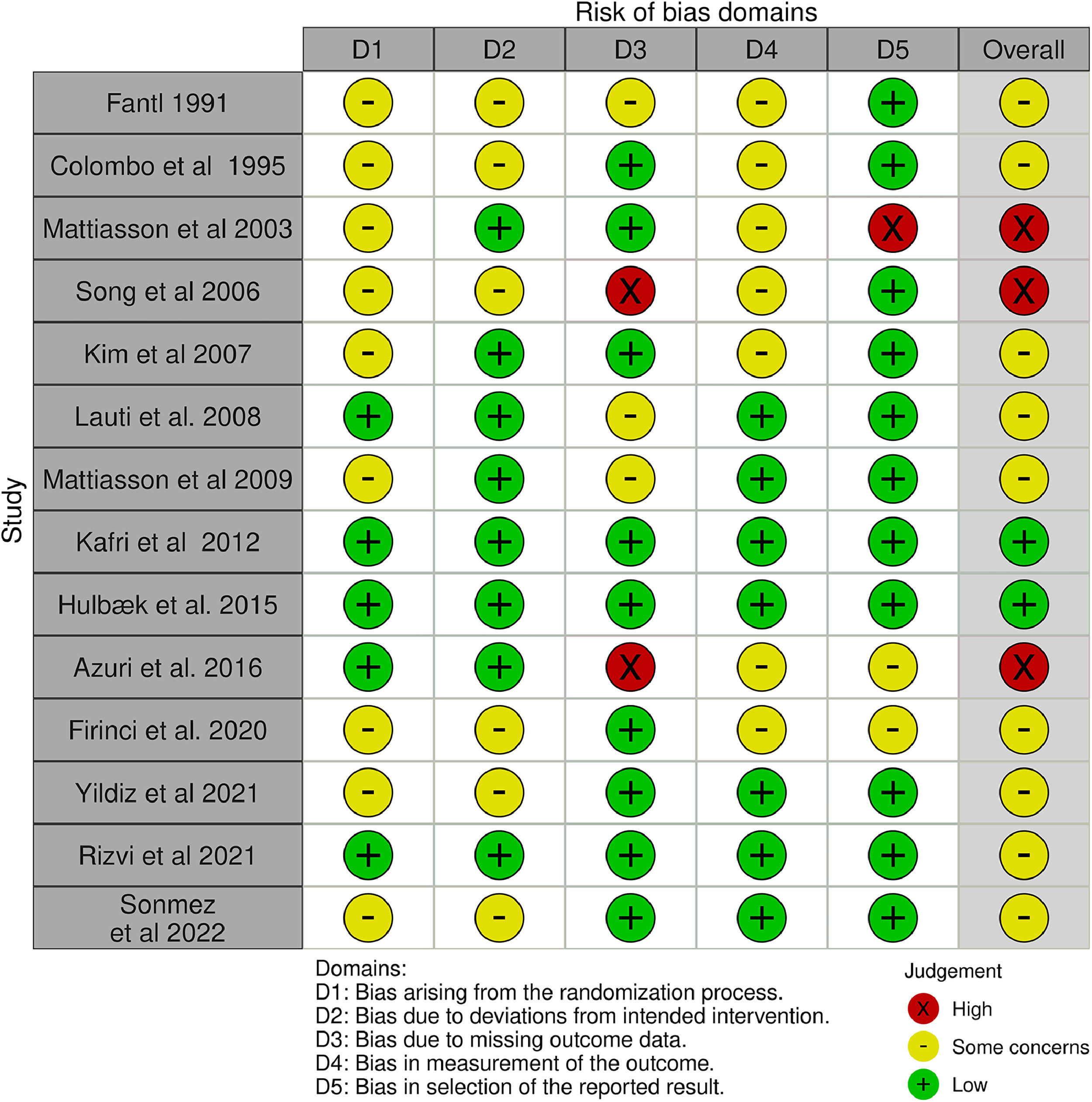

Risk of biasSome studies did not provide detailed information on how the participants were assigned to different groups.40-42,48,50 Other RCTs randomized subjects using sealed envelopes while maintaining a 1:1 ratio.39,43,47,49,51 Computer-generated randomization lists were used in some studies, and randomization was performed in blocks of four (Fig. 2)38,44-46 (Also see Supplementary material online 2).

Of the RCTs, 9 assessed nocturia, 13 assessed symptom frequency, 6 assessed urinary urgency, and 11 assessed UI as primary outcomes. A bladder diary was the most common method of assessing OAB symptoms. QoL was evaluated in seven RCTs using different measures, including the Incontinence Impact Questionnaire Short Form and Long Form (IIQ-SF7, IIQ-7), the Incontinence Quality of Life Questionnaire (I-QoL), and the total health-related quality of life (HRQL) score from the International Consultation on Incontinence Questionnaire Overactive Bladder Quality of Life Module (OAB-q). AE were observed in 12 RCTs, including dry mouth, constipation, nausea, dizziness, reduced visual acuity, tachycardia, headache, reduced appetite, low back pain, pain in the extremities, vaginal irritation, and fatigue (Table 1)38–51 (Also see Supplementary material online 3).

The duration of treatment in the reviewed studies varied from 6 to 48 weeks presented with a mean duration of 20.85 (SD, 15.61). This created heterogeneity in the comparative studies examining BT alongside other therapies.38–51

The duration for which BT was studied and monitored varied across the studies. Most studies had a short-term follow-up, and total durations ranged from six weeks to four years.38–51 Participants’ tolerance determined a gradual increase of 15 to 30 min each week in the intervals. The programs aimed to achieve a voiding interval of 2.5 to 4 h while implementing strategies to suppress urinary urgency.38-51 The participants were provided with education and orientation on the anatomy of the pelvic floor and bladder function, which enabled them to effectively manage their OAB symptoms using the bladder diary.43–51

Bladder training (BT) versus drug treatment (DT)Eight RCTs used DT,38,39,41–46 two used anticholinergic drugs,41,44 and six compared BT with other drugs (nonanticholinergic and nonadrenergic agonists).38,39,42,43,45,46

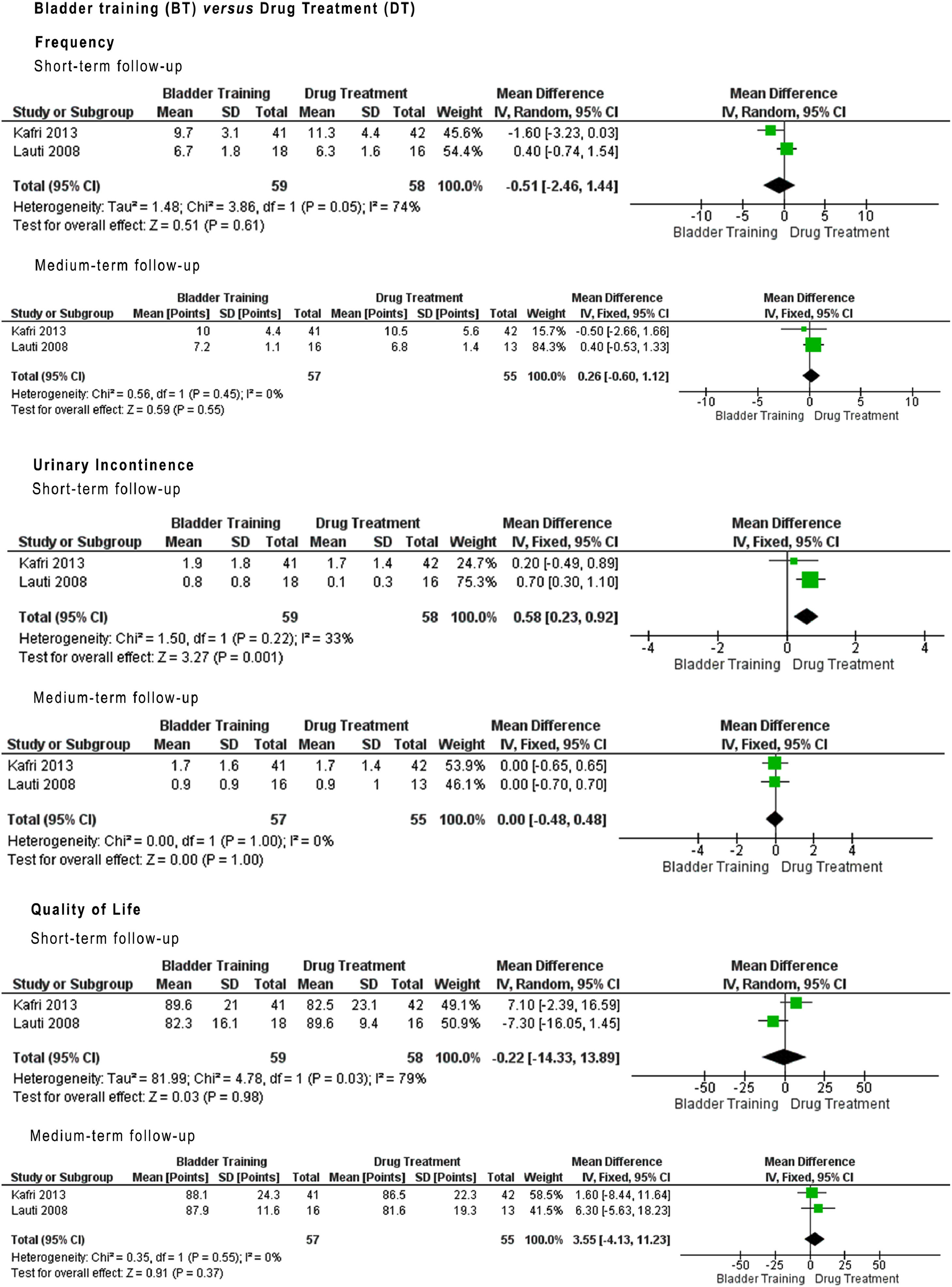

Comparing frequency in relation to isolated BT versus DT, at short- and medium-term follow-up, none of the evaluated groups showed difference in results. The certainty according to the GRADE approach was determined as “very low” and “critical” owing to inconsistency, imprecision, heterogeneity, and the overall effect differences not being significant. For UI, at short-term follow-up, the results favored BT over DT (MD: 0.58, 95% CI: 0.23, 0.92). However, at medium-term follow-up, the results were not significant, and the GRADE scores assigned were “very low” and “important” (Fig. 3) (Also see Supplementary material online 4).

Meta-analysis bladder training (BT) vs drug treatment (DT).

In the studies reviewed, BT in combination with other therapies (CT) yielded very diverse results. Specifically, 11 studies administered only BT, while 10 incorporated BT in a combination with other thepaties.38,39,42–48,50 BT was combined with DT in five studies.38,39,42–44 BT, PFMT, and behavior therapy were combined in two RCTs.45,46 Two studies employed BT and IVES,47,48 and one RCT used BT with either PTNS or TTNS.50

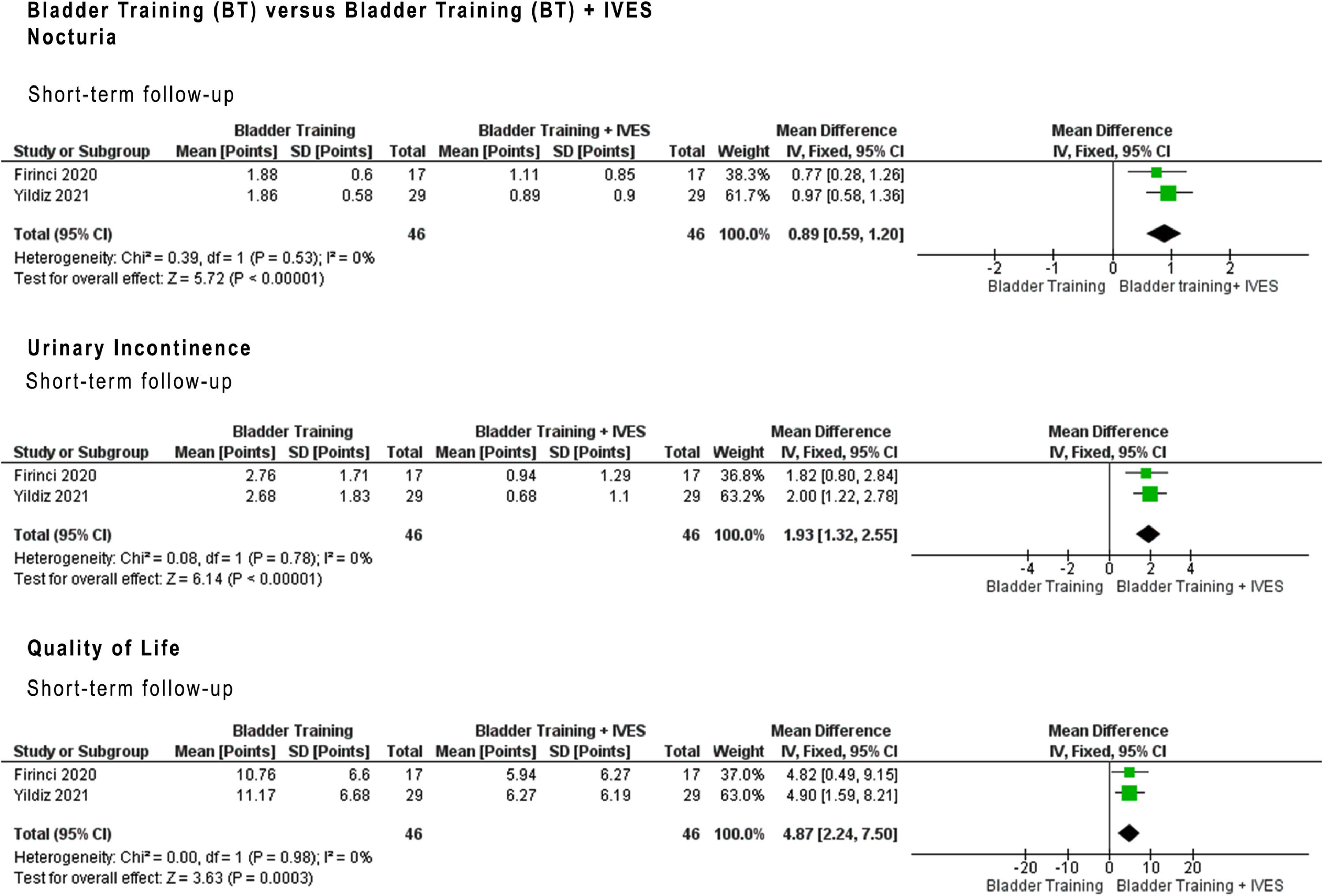

BT versus BT plus intravaginal electrical stimulation (BT + IVES)Two RCTs used IVES to manage OAB symptoms among participants.47,48 BT+IVES yielded better outcomes for nocturia compared to isolated BT, but there was no report on UI for this comparison. For UI, the BT+IVES group showed significantly better results than isolated BT.

In the BT+IVES group, 13 participants showed improvements in OAB symptoms (44.8%).48 However, 15 participants perceived no change after the BT intervention (51.7%).48 Two studies demonstrated notable improvements in QoL.47,48 The group treated with BT+IVES had significantly better QoL scores, as assessed by total HRQL scores on the OABq, which were greater than the improvements seen in the isolated BT group.47 Moreover, a significant improvement in QoL was observed in the BT+IVES group, as assessed by the IIQ-7, compared to the isolated BT group.48

For isolated BT versus BT+IVES, nocturia, UI, and QoL at short-term follow-up were better in the BT+IVES group, but the likelihood of recommending this intervention based on the quality of the evidence is “low” owing to the risk of bias, which was determined as “important” for the importance of the recommendation, as dictated by the GRADE approach. Nocturia at short-term follow-up showed significant values (MD: 0.89, 95% CI: 0.59, 1.13), as did outcomes for UI (MD: 1.93, 95% CI: 1.32, 2.55), and QoL (MD: 4.87, 95% CI: 2.24, 7.50), as shown in Fig. 4 (Also see Supplementary material online 5).

Meta-analysis bladder training (BT) vs bladder training plus intravaginal electrical stimulation IVES (BT + IVES).

BT plus ES yielded significant improvements in nocturia, UI, and QoL. However, AE were reported due to discomfort resulting from electrode placement techniques or electrical currents, as they also were in the RCTs that used ES+BT.47,48,50 The parameters for the two types of ES varied among the three RCTs. Two RCTs used 10 Hz, a 5–10-s work–rest cycle, and 100-ms pulse width IVES.47,48 A symmetrical biphasic pulse wave was administered at an intensity range of 0–100 mA for a duration of 20 min 3 times weekly for 8 weeks, comprising a total of 24 therapy sessions.47,48 The intensity was based on participant-reported discomfort levels,47,48 with some ES recipients reporting discomfort caused by electrode placements or electrical currents.47 Three participants reported vaginal irritation, including one in the ES group and two in the CT group.47

BT versus BT plus drug treatment (BT + DT)The BT+DT studies improved OAB symptoms, particularly UI.42 Five RCTs decreased frequency.38,39,41,42,43 CT with DT was more effective than isolated BT in terms of decreasing frequency.38,42,43 Conversely, no significant difference was seen in UI when comparing BT and DT or comparing isolated BT with BT+DT. Some RCTs that included DT groups reported some AE in these groups (specifically, dry mouth in six RCTs).38,39,41,42,44,45

BT isolated and with other interventionsOne study assessed nocturia, frequency, and UI, reporting a substantial increase in frequency compared to the baseline and other groups.40 The use of PFMT and biofeedback seems to have had a beneficial effect in combination with BT, notably improving most OAB symptoms, except for UI.49 Two RCTs studied the use of biofeedback, showing positive results in OAB symptoms and QoL.47,49 One RCT compared different ways of offering treatment, using BT without improving OAB symptoms.51 Fourteen AE were reported in the sample, with only one event possibly related to BT. This event involved increased voiding frequency and was treated with antibiotics by a general practitioner.51 One RCT presented data on sample loss, with approximately 29% of the participants leaving the study (n = 14); the authors noted a potential for demotivation both when BT was isolated and in terms of motivation.51

Publication biasFunnel plots showed no clear asymmetry in any of the comparisons. However, it is important to interpret these findings with caution, as there were limited studies suitable for this type of analysis. The limited number of RCTs impedes the assessment of potential publication bias (Also see Supplementary material 6).

DiscussionBT has been used for decades in clinical practice to treat OAB symptoms.22,23 We found that BT+IVES had a more significant impact at short-term follow-up for nocturia, UI, and QoL than isolated BT. Additionally, we determined that DT was more effective in improving UI than isolated BT. However, according to the GRADE approach, the RCTs assessed relied on low-quality evidence.

The International Continence Society and AUA/SUFU endorse BT as a primary approach for addressing OAB symptoms.1,2,21 There are theories that BT may be beneficial for OAB symptoms.1,2,21–24,26,52 These advantages include enhanced inhibition of detrusor contractions in the cortical area during the filling phase, enhanced urethral occlusion during bladder filling caused by cortical facilitation, and central modulation of afferent sensory impulses.21–24,26,52 Thus, individuals who undergo behavioral therapy become more cognizant of their health status and better understand the factors that can lead to OAB symptoms.21–23,26

According to Wallace et al.,26 BT may be useful in the treatment of OAB symptoms, but there was insufficient evidence to determine whether BT is useful in combination with another therapy. In the present review, BT+IVES yielded improvement in OAB symptoms at short-term follow-up. Participants in BT+IVES groups may have increased their awareness of or gained additional experience with PFM functions.22,53 Another factor to consider when using BT+IVES is the additional time spent with healthcare professionals.47,48

The literature indicates that ES is effective and safe for managing OAB symptoms and improving long-term QoL. These therapeutic benefits are supported by multiple sources.17,52,53,54 ES can stimulate the perineodetrusor inhibition reflex via vaginal electrodes. This stimulation activates the efferent motor fibers of the pudendal nerve, causing PFM contractions that help to inhibit detrusor contractions. This review observed and analyzed IVES protocol use but could not compare BT with other peripheral ES modalities, unlike the study by Zomkowski et al.47,48,54

Although there has been a recent increase in the number of relevant RCTs, several limitations were identified in the studies. These include the use of various instruments, differences in sample profiles, a lack of follow-up information, and limited eligibility for meta-analysis due to a lack of information on statistical methods (intention-to-treat). Additionally, a variety of protocols and differences in symptom severity and sample characteristics were observed. Two RCTs had comparable samples and follow-up. Both groups were included to enable a comparison of follow-up at different times. A meta-analysis conducted by Kafri et al.45 compared another RCT during the medium-term follow-up period.44–46 Additionally, it is possible that some studies that met the review's eligibility criteria were not included because they were not published in the journals in the databases searched.

A comprehensive search of several databases was performed to maximize the inclusion of RCTs, and English was chosen as the eligibility criteria. Yet some ongoing or unpublished RCTs may not have been included. In addition, it is difficult to understand the impact of BT on OAB symptoms due to its subjective and complex characteristics.

BT yielded fewer AE than other treatments. This indicates that combining BT with other therapies may be a safer and less costly solution for treating OAB symptoms.2,21,22,26 However, the findings of the review are limited to the RCTs analyzed, and further research is necessary to confirm the results and compare the safety profile of BT with those of other interventions.

Although the analyses indicate that BT+IVES is more effective for OAB symptoms and QoL, and that DT is more effective for UI than isolated BT, the RCTs do not provide sufficient evidence to support the recommendation of this therapy in clinical practice.

ConclusionBased on the studies reviewed, compared to isolated BT, BT+IVES yields improvements in nocturia, UI, and QoL in individuals with OAB symptoms, with short-term benefits. There are few RCTs on the effect of BT on OAB, especially on urinary urgency, making its effect inconclusive.