Infertility is a rising global issue and when compared to men, women face greater stigma and consequences of infertility in developing countries. Women are prescribed exercises as a part of lifestyle intervention programs prior to artificial reproductive techniques (ART) to lose weight, to improve their chances of conception. However, adherence to exercise programs has been observed to be poor and the reasons for this remain less explored.

ObjectiveTo explore the perceptions and practices about performing exercises among women with infertility.

MethodsA qualitative explorative study was conducted based on the interpretive framework. Face-to-face semi-structured in-depth interviews were conducted with 20 women diagnosed with primary or secondary infertility. Data were analyzed using thematic analysis.

ResultsA total of 20 women, mean age 30.9 ± 4.8 years, body mass index 22.4 ± 1.9 kg/m2, participated in the study. Four main themes were constructed: (1) knowledge about the causes of infertility - obesity and lifestyle changes; (2) modifications made in physical activity for conception - performing household chores, not exercising during menstruation, and reducing physical activity during or before Assisted Reproductive Techniques (ART); (3) perceptions towards health and fitness - lack of health problems, being strong and happy; (4) exercise and conception - perceived benefits of exercises, source of knowledge about exercises, preferred type of exercises, willingness to exercise, facilitators and barriers to exercise.

ConclusionKnowledge about the causes of infertility, individual perception of health and fitness, the preferred mode of exercise, and barriers and facilitators to perform exercise are key aspects to be considered before planning an exercise intervention for women with infertility.

Infertility is a rising global issue as it leads to a reduced level of personal well-being and acts as a significant life challenge to those who desire to have children.1,2 In comparison to men, women face greater stigma and consequences of infertility in developing countries.3

Major factors associated with infertility among women are increasing marital age, obesity, polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS), endometrial tuberculosis, and sedentary behaviour.4–8 A previous study has reported that each unit increase in body mass index (BMI) predicted a 3% increase in the risk of infertility when BMI was >19.5 kg/m2.9 Previous studies have reported that a 5–8% reduction in BMI can be associated with a positive impact on reproductive hormones resulting in increased ovulation, pregnancy rate, and live birth rates.10,11

Physical activity is defined as any bodily movement produced by skeletal muscles which results in energy expenditure whereas exercise is a subset of physical activity that is planned, structured, and repetitive for improving or maintenance of fitness.12 As per the recommended physical activity guidelines, an adult must do moderate-intensity aerobic exercise for 150 to 300 min, or 75 to 150 min of vigorous-intensity aerobic exercise, or an equivalent combination of moderate to vigorous physical activity weekly.13 A recent systematic review has reported that the reproductive functions of women with PCOS can be improved with physical activity and can also reduce infertility among these women.14 However, no clear consensus has been reached on the type and duration of exercises to improve fertility outcomes.15

Although the desire to conceive and the stigma of childlessness are strong motivators to exercise in women with infertility,16 a median dropout of 24% in lifestyle intervention has been reported.17 Hence, we aimed to explore the perceptions towards exercise behaviour in women with infertility. Identifying these factors may enable the development of strategies to improve exercise adherence and structured lifestyle intervention programs in this population.

MethodsDesign and settingA qualitative study, applying a face-to-face semi-structured in-depth interview technique, was conducted at an assisted reproduction centre in a tertiary care hospital in South India. A qualitative exploratory study was conducted based on an interpretive framework18 and the reporting is done based on the Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research (SRQR)19 and Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research.20 The study obtained ethical clearance from the Institutional Ethics Committee of Kasturba Hospital, Manipal (IEC-51/2019). Written informed consent and consent for audiotaping the interview was obtained from the participants. The study trial was registered under Clinical Trial Registry-India (CTRI/2019/06/019486). The current paper reports on Phase I of the study. Phase II was a cross-sectional survey conducted using a questionnaire which was based on the themes developed in Phase I and is published elsewhere.21

ParticipantsTwenty women with infertility (either primary or secondary infertility) between 18 and 45 years of age, who were yet to undergo any type of assisted reproductive technique, were enrolled in the study. The exclusion criteria included women with unstable health conditions who had contraindications to exercise and who had been diagnosed with psychiatric conditions.

Reflexivity and researcher characteristicsThe primary investigator GS who conducted the interview was pursuing her Master's degree in Physical Therapy during the study period. PR, BKR, AB, and PK are researchers with more than 25 years of experience who were familiar with the beliefs, practices, and vernacular language of the participants. Participants were encouraged to share their experiences with the least possible impact from the interviewers’ pre-understanding.

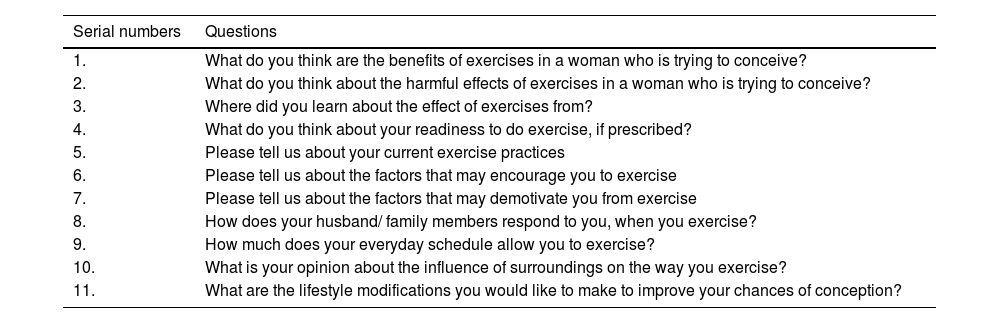

Data collectionThe interview guide (Table 1) was developed based on the literature review, the theory of planned behaviour,22 and the expert opinions of the investigators. After collecting the demographic details, the primary investigator who conducted the interview discussed the health concerns of the participant. After building the rapport, the interview was audio recorded. Based on the participants’ preference, they were interviewed in English or Kannada language, in a well-ventilated room in the assisted reproduction centre located within a tertiary hospital. Each interview lasted for an average duration of 45 min and probes were used to obtain additional information. Field notes were taken during the interviews. Data collection continued until no new information emerged and thematic data saturation was attained. The interviews conducted in the Kannada language were translated into English. All the audio recordings were transcribed into English by the primary investigator.

Interview guide.

Interviews were analysed using seven stages of the framework approach.23 Two researchers (GS and PR) did independent coding of the first 10 transcripts, to understand any alternative viewpoints. Coding was achieved using the Atlas Ti software for storing and systematizing the data for the analysis process. We identified 424 codes during the process. The investigating team met to finalize the Priori and Posteriori Codes which collapsed into 26 code families and then into sub-themes. Important quotes were reviewed from each transcript and were used to support the description of each category and theme.

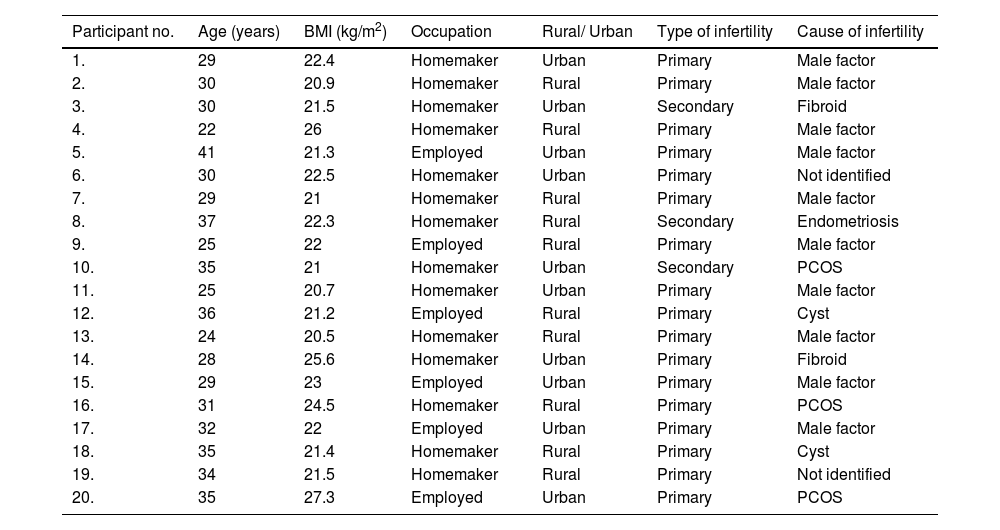

ResultsA total of 36 women were screened, out of which 16 were excluded: seven did not want to discuss their personal views and nine due to lack of time. The demographic details of the participants are described in Table 2. A total of 20 women with a mean age of 30.9 ± 4.8 years and a BMI of 22.4 ± 1.9 kg/m2 from mixed rural and urban settings were included in the study. Most of our participants belonged to the normal BMI category.

Demographic details of the participants (n = 20).

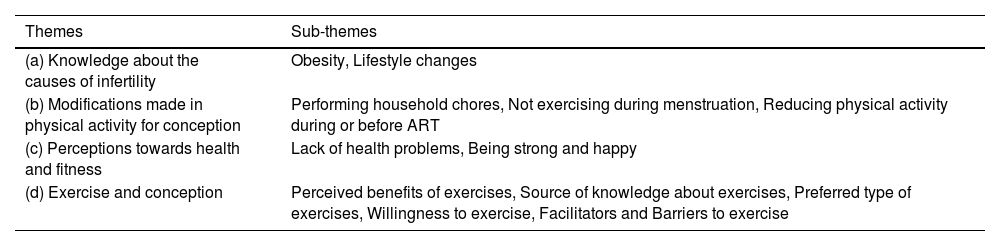

The list of themes and sub-themes that emerged are represented in Table 3. Four main themes were constructed based on participants’ perceptions. Few quotations are mentioned in the description. Each participant is assigned a number to ensure anonymity.

- (a)

Knowledge about the causes of infertility

- (i)

Obesity

- (i)

List of themes and sub-themes.

The most often reported causes of infertility by our participants were being obese or overweight. They believed that weight gain harms their overall health and conception. Obese or overweight women were often advised by doctors to exercise and follow a healthy diet.

“I think because I am overweight, there is hormonal disturbance, so that is why maybe I am not able to conceive.” (P04)

Our participants reported the causes of infertility as being overweight or obese, which may lead to hormonal imbalance thus causing infertility and irregular menstrual cycles.

- (ii)

Lifestyle changes

- (ii)

Most women reported that lifestyle changes between generations is a major factor leading to infertility. Women perceived that following the traditional lifestyle that is, following indigenous and ancient cultural practices in terms of nutrition and physical activity is good for their general health. “I have mechanical home appliances that have reduced my level of physical activity, unlike my mother or grandmother who used to be physically more active because they had to depend on grinding stones, washing clothes using hand, drawing water from well etc for doing their daily household chores. (P13)

Our participants from rural backgrounds believed that changes adopted in their methods of performing household chores and the availability of mechanical appliances reduced their physical activity level, negatively influencing their health and chances of natural conception.

- (b)

Modifications made in the level of physical activity to facilitate conception

Participants made modifications in daily physical activities as advised by colleagues, friends, family members, and other women who conceived with difficulty.

- (i)

Performing household chores

Employed participants reported difficulty in dedicating specific time for exercises and hence they tried to do the household chores thus increasing their level of physical activity. ” My colleagues told me that being obese reduces the chances of becoming pregnant. So I decided to lose weight and I believed that the easiest way would be by doing all household chores by myself.” (P20)

- (ii)

Not exercising during menstruation

Elders at home advised women to remain less physically active and exercise cautiously during their menstruation. They were strictly instructed to avoid strenuous work, lift heavy weights, and were encouraged to rest during their menstruation. “So, I decided to exercise …but during periods; I do not do heavy work …I rest completely.” (P14) “When we have periods…if we exercise, it stresses us more and can affect our bleeding. After exercising, I would not be able to stand and walk for a long time, as I will be tired. So, I do not think we should exercise during periods.” (P01)

Few participants believed that women must not exercise during menstruation as it may affect their overall health and affect the chances of conception.

- (iii)

Reducing physical activity during or before Assisted Reproductive Techniques (ART)

Irrespective of their educational background, most of our participants believed that they must not be involved in physical activity before and during the ART as it may affect the success of the treatment procedure.

“I am not aware of the recommended level of physical activity as per guidelines. I believe that we should do little physical activity before and during the treatment (IVF) and not strain the body to an extent, that it affects the results of the procedure.”(P13)

- (c)

Perceptions towards health and fitness

Most participants perceived fitness as a “lack of health problems”. They also associated it with “being strong and happy”. Perceptions and behaviours towards fitness varied based on the setting and occupation.

Women from rural areas, who lead an active lifestyle, have defined fitness in terms of their physical health. Being involved in household activities that require manual effort has been associated with fitness.

“We have so much work in villages that we are all so active…we don't gain weight, we don't get health problems, I think it is enough to keep me fit…” (P12)

Few participants, especially from urban areas, performed exercises such as walking, yoga, and strengthening exercises, as they felt household activities would not suffice. “I do very little work…so, I do not think it will be enough to keep me fit. Hence, I go for walks” “I do not think that I am fit…I am stressed, I cannot sleep properly”. (P14)

Participants expressed that they are “stressed”,” tired”, “worried”, and “restless” most of the time.

- (d)

Exercise and conception

- (i)

Perceived benefits of exercises

- (i)

Participants opinioned that exercising improves the strength of muscles, promotes relaxation, reduces body pain, reduces stress, and promotes psychological well-being. They reported that exercise before conception prepares a woman's body for pregnancy. ” Exercise has multiple benefits…It helps me to maintain my body, strengthen it, and make me physically and mentally healthy…It keeps me fit.” (P16)

- (ii)

Source of knowledge about exercises

- (ii)

Participants gained knowledge from social media, doctors, and relatives.

“I follow Facebook or Instagram pages related to exercise and know about its importance. If I don't understand, I google to know more. I am so desperate to conceive.” (P17)

- (iii)

Preferred type of exercises

- (iii)

The preferred types of exercises by the participants were walking and yoga. Walking was the most preferred as they believed that it did not require supervision, due to ease of performance and lack of complexity. They followed a light to moderate intensity (based on Borg rating of perceived exertion scale),24 for a duration of 20 to 30 min a day for approximately 4 to 5 days a week. ” I would prefer mainly walking …outside the house. I feel energetic and more refreshing due to change of environment” (P14) ” It is more comfortable and better to exercise within home…I can decide what I want to do and where and when I want to exercise… Every day, I will not get time to exercise at the gym” (P05)

The preference for indoor or outdoor exercise depended on how comfortable the participants felt. Many preferred exercising indoors following YouTube videos or reference materials. They believed that the ability to perform the exercises themselves gave them more privacy and a feeling of empowerment.

- (iv)

Willingness to exercise

- (iv)

Participants had a mixed response when they were enquired about their willingness to exercise. ” Because I have a busy schedule, I do not have time for exercise. I believe that the amount of work I do is already more than required, hence I do not need to exercise...”(P16)

Most women were willing to exercise if that could help them to conceive or if doctors advised them to exercise. Few women did not want to exercise as they perceived themselves to be fit enough to conceive without exercising.

- (v)

Facilitators to exercise

- (v)

Availability of space and strong family support were reported as major facilitators of exercise. They expressed gratitude for any contribution or support provided by their husband and other family members towards their well-being. “My husband shares the work and lends me help to do household chores so that I get enough time to exercise. I am ever grateful to him.” (P10)

- (vi)

Barriers to exercise

- (vi)

The reported barriers were lack of family support and time, lack of motivation, and inquisitive neighbours. “Curious neighbours”, “taunts from family members”, and resultant discussions contributed to the feelings of “guilt” and “shame” among the participants. “I am often ridiculed for not having conceived by my relatives at family gatherings. Whenever people blame me for being “barren”, I get depressed and feel guilty.” (P13)

Few women reported that they do not get free time to exercise due to heavy household chores and have the obligation of taking care of the elderly at home. Participants who were employed felt exercise was “exhaustive” as they had to manage both job and household chores by themselves.

DiscussionThis study provides key insights into the context and challenges that determine exercise behaviour among women with infertility. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study from South Asia to explore the perception of health and exercises among women with infertility.

Participants in our research reported obesity and altered lifestyle as major factors for infertility. It was believed to cause irregularity of menstruation and affect fertility. A previous survey conducted among women with infertility reported that 82.7% of the participants considered obesity to increase the chances of infertility.25 Obesity alters the hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian axis causing ovulatory dysfunctions and oocyte impairments, thus affecting reproduction.26

Participants in this study reported that their current physical activity levels are lower, compared to previous generations, and this could be a major reason for infertility. They believed that mechanization has reduced manual efforts resulting in obesity and in turn, increased the rate of infertility among women. Participants in a previous study on their perceived barriers and facilitators to physical activity have reported similar findings.27 However there was a lack of awareness among our participants about the recommended level of physical activity as per the guidelines.13 Reasons for infertility in women may be due to ovarian, tubal, or uterine causes, but sometimes, the cause remains unknown.28 However, our participants were not aware of the other causes of female infertility. The primary causes of infertility among 10 of our participants were male-related causes such as reduced sperm count, poor quality of sperm etc. However, the women blamed themselves for infertility. It has been reported that in Indian society, childbearing is considered necessary,29 and infertility is considered a woman's problem, thus she is blamed for not being able to procreate.30 This implies the necessity to spread awareness about the causes of infertility among the general population so that necessary measures can be taken based on the root causes rather than only “blaming” the women for the primary reason for infertility.

Only a few participants in our study believed that they must remain physically active before or while undergoing the procedures to conceive. Our findings contradict the results of a previous study which reported that the majority of participants preferred to exercise during IVF.31 Most of our participants believed that exercise during the procedure would impair fertilization and prevent pregnancy. Similar to our findings, participants from a previous study believed that there would be a negative effect on the outcome of their treatment if they did not limit their physical activity.32 A previous study has reported that there is no positive or negative association of physical activity with pregnancy outcomes in fresh embryo transfers, including during the critical period of embryo implantation.33

Our participants had a misconception that they must not do exercise and must rest during menstruation to maintain good health and prevent dysmenorrhea as advised by elders in the family. A previous study has reported the benefits of exercise during menstruation on physical and mental health.34 However, previous literature has reported that intense exercises can result in low energy availability which leads to reduced luteinizing hormone, which diminishes ovarian stimulation and estradiol production leading to menstrual disorders. Hence avoiding high-intensity exercises during menstruation may be beneficial.35

In our study, we found that social media, doctors, and family members were the sources of information for knowledge about the effects of exercise. A UK-based study has reported that information obtained from the health care providers was insufficient and hence, additional information was sought by the participants from the internet and other consultants.36 Another study reported that people preferred to collect information from reliable hospital sites on the internet as they found it embarrassing to indulge in a face-to-face discussion about fertility-related issues with doctors.37 However, participants sought information from the internet about infertility, its causes, and treatment methods but not regarding physical activity or exercise recommendations. This brings out an important lacuna in the dispersion of knowledge about the role of physical activity and exercises in this population by physical therapists. Spreading awareness about the role of physical therapy and appropriate physical therapist referrals of these women by practicing gynecologists may result in better patient outcomes.

Our participants who exercised followed low to moderate-intensity exercises. However, the overweight participants in our study did not follow the recommended guidelines for weight loss which include 250 min of moderate-intensity walking or activity for weight loss.38 Despite being in the normal BMI category, most of our participants were motivated to exercise as they were aware of other health benefits of exercise including psychological well-being. The benefits of exercise on mental health have been reported in previous literature.39

The preferred types of exercise by participants in the current study were brisk walking and yoga. To the best of our knowledge, no previous studies have reported exercise behaviours and preferences in women with infertility. Previous systematic reviews have reported the benefits of yoga in reducing BMI in overweight, obese, or individuals with metabolic syndrome.40,41 An Indian study has reported that both walking and yoga were preferred exercises by their participants.36 Similar activity preferences were reported by studies done in other populations.42–45

Our study participants reported support and help from family, availability of open spaces and knowledge about the health benefits of exercise as facilitators to exercise. They also reported that their families would help and encourage them to make decisions on their own. Previous literature about physical activity perceptions of women in Ghana also reported knowledge about health benefits as a facilitator to exercise.46

In our study, lack of family support, time, motivation to exercise, and inquisitive behaviour of neighbours/relatives were reported as barriers to exercise by the participants. Some participants mentioned laziness and lack of interest as reasons for not exercising. Previous literature has reported a lack of willpower, lack of money, lack of social acceptance of walking and feeling shy/embarrassed, and unavailability of facilities as barriers to exercise, in addition to those identified in our research.36,46

Implications to education and clinical practiceThis study warrants the necessity to implement health education and awareness programs regarding the importance and benefits of exercise in this population especially about the physical activity guidelines. This will help to counteract the prevailing myths regarding exercise prescription, the relationship between menstruation and exercise, and the general benefits of exercise, and thus improve the adherence to exercise among women with infertility. The study findings also signify the importance of physical therapy and the role of physical therapists in the prescription of exercises in women with infertility.

Strengths and limitationsThe design of the current study facilitated obtaining sensitive and commonly unexpressed thoughts. However, as all the participants were natives of South India, our results cannot be generalised due to varying cultural contexts. In our study, very few participants were overweight or obese, and hence the perception of exercise practices among overweight/obese women with infertility remains understudied. Future research could focus on obese or overweight women with infertility at the community level (both in rural and urban settings) as it would provide unique perspectives about their perception of exercise.

ConclusionThe results indicate that obesity and altered lifestyle are perceived as major causes of infertility. Women often sought information about exercises from social media, doctors, and family members. Most women were willing to exercise if advised by doctors and the preferred types of exercises were brisk walking and yoga. Supportive families and the availability of facilities were the main facilitators for exercise practice. Common barriers to exercise were lack of awareness, lack of time and motivation, and lack of family support.

The authors thank all the participants of this study. We would like to thank the Transdisciplinary Center for Qualitative Methods, Manipal Academy of Higher Education, Manipal for permitting us to use the ATLAS ti software for data management.

Institutional Ethics Committee: Kasturba Hospital, Manipal (IEC-51/2019)

Trial registry number: Clinical Trial Registry-India (CTRI/2019/06/019486) https://ctri.nic.in/Clinicaltrials/login.php