The Animated Activity Questionnaire (AAQ) was developed in the Netherlands to assess activity limitations in individuals with hip/knee osteoarthritis (HKOA). The AAQ is easy to implement and minimizes the disadvantages of questionnaires and performance-based tests by closely mimicking real-life situations. The AAQ has already been cross-culturally validated in six other countries.

ObjectiveTo assess the cross-cultural validity, the construct validity, the reliability of the AAQ in a Brazilian sample of individuals with HKOA, and the influence of formal education on the construct validity of the AAQ.

MethodsThe Brazilian sample (N = 200), mean age 64.4 years, completed the AAQ and the Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Index (WOMAC). A subgroup of participants performed physical function tests and completed the AAQ twice with a one-week interval. The Dutch sample (N = 279) was included to examine Differential Item Functioning (DIF) between the scores obtained in the Netherlands and Brazil. For this purpose, ordinal regression analyses were used to evaluate whether individuals with the same level of activity limitations from the two countries (the Dutch as the reference group) scored similarly in each AAQ item. To evaluate the construct validity, correlation coefficients were calculated between the AAQ, the WOMAC domains, and the performance-based tests. To evaluate reliability, the Cronbach's alpha coefficient, the intraclass correlation coefficient, and the standard error of measurement (SEM) were calculated.

ResultsThe AAQ showed significant correlations with all the WOMAC domains and performance-based tests (rho=0.46–0.77). The AAQ showed high internal consistency (Cronbach's alpha=0.94), excellent test-retest reliability (ICC2,1 = 0.98), and small SEM (2.25). Comparing to the scores from the Netherlands, the AAQ showed DIF in two items, however, they did not impact on the total AAQ score (rho=0.99).

ConclusionOverall, the AAQ showed adequate cross-cultural validity, construct validity, and reliability, which enables its use in Brazil and international/multicenter studies.

Osteoarthritis is one of the most prevalent musculoskeletal diseases worldwilde1,2 and a leading cause of disability.1 According to a systematic review, the prevalence of hip and knee osteoarthritis (HKOA) in the adult population is 11% and 24%, respectively.3 Its occurrence is expected to increase significantly in the future due to the aging process and the higher prevalence of obesity, two major risk factors of this health condition.4 HKOA imposes a huge burden to the population because pain and stiffness in these large weight-bearing joints often lead to disability by compromising mobility and the execution of activities of daily living.5

The assessment of activity limitations in individuals with HKOA is essential to monitor the clinical course of the disease and to evaluate the effectiveness of therapeutic approaches.6 The Lequesne's Algofunctional Questionnaire and the Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Index (WOMAC) assess symptoms and physical function in individuals with HKOA and are both validated in Portuguese language.7,8 However, they are subjective and highly dependent on the individual's reference frame.9 In contrast, performance-based tests are used to objectively measure the capacity of an individual to perform specific tasks, but they might be considered cumbersome for some individuals, and require the physical presence of the individual.6 Moreover, tests performed in a clinical setting are known not to represent a real-life situation.10

The Animated Activity Questionnaire (AAQ) was developed in the Netherlands (http://www.kmin-vumc.nl/_16_0.html)11 as an innovative method to assess activity limitations in individuals with HKOA.12 It consists of video animations of 17 basic daily activities performed with different levels of difficulty. The individuals choose the animation that best matches their performance. The AAQ combines the advantages of performance-based tests and self-report questionnaires and minimizes their disadvantages by closely mimicking real-life situations.13 Moreover, the AAQ is easy to implement, inexpensive, and the individual's presence in a clinic is not required.6 So far, the AAQ has shown good content and construct validity6,13,14 and excellent test-retest reliability15 and responsiveness at six months follow-up.16

The AAQ has great potential for international use and has been cross-culturally validated in six European countries.6 Cross-cultural validity refers to the extent the performance on a translated or culturally adapted instrument is an adequate reflection of the performance of items in the original version of the instrument.17 Cross-cultural validity may be assessed by Differential Item Functioning (DIF) analyses.18 For adequate cross-cultural validity, individuals from different countries with the same level of activity limitations should have the same score on each AAQ item.17

Therefore, to enable the use of the AAQ for clinical and research purposes in Brazil and multicenter/international studies, this study aimed to assess the cross-cultural validity, the construct validity, and the reliability of the AAQ in Brazilian individuals with HKOA. As a secondary aim, we assessed the influence of formal education on the construct validity of the AAQ. Because the AAQ showed good cross-cultural validity in six other countries when compared to the Netherlands data, and also good construct validity and reliability, we hypothesized that the AAQ would present overall good validity and reliability in the Brazilian individuals. Also, because no comprehensive language understanding is necessary to choose the videos, there would be no influence of formal education in the construct validity of the AAQ.

MethodsStudy design and participantsA cross-sectional study was conducted in the municipality of Diamantina (47 617 inhabitants), Minas Gerais, Brazil. A convenience sample of men and women (≥45 years),19 with a clinical diagnosis of HKOA according to the American College of Rheumatology criteria,20,21 and able to ambulate with or without walking aids, was recruited from an outpatient rheumatology clinic and primary care units. The exclusion criteria were cognitive impairment, severe visual or auditory deficit, or any medical condition other than HKOA that could hamper activity. The goal was to test 200 participants to evaluate cross-cultural validity, as recommended for DIF analyses,22 and at least 50 participants to evaluate construct validity and reliability, as recommended by international guidelines.23 This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Universidade Federal dos Vales do Jequitinhonha e Mucuri (2.451.189). All participants included in the study were informed about the contents of the study and signed a written informed consent before inclusion.

MeasuresThe AAQ contains videos of 17 basic daily activities: ascending and descending stairs; walking outside on a flat surface; walking on uneven terrain; walking inside after at least 15 min of sitting; walking up and down a slope; picking an object from the floor; rising from the floor; rising from and sitting down on a chair, on a sofa, and on a toilet; putting on and taking off shoes. For each activity, three to five videos are shown with an increase of difficulty of performance, resulting in 3–5 response options with scores of 33, 67, and 100; 25, 50, 75, and 100; 20, 40, 60, 80, and 100, respectively. Each activity also offers the response option ‘unable to perform.’ The score for this last option is 0 in all the questions. The total score is the mean from the 17 activities, varying from 0 to 100, with lower scores indicating higher levels of limitation in activities.13

Although the AAQ answers are based on video animations, without language interference, for the purpose of this study, the instructions of the questionnaire were translated to the Portuguese language according to international guidelines,24 which consists of six stages. In stage 1, the instructions were translated into Portuguese by two independent bilingual translators who were native Portuguese speakers. In stage 2, the two translations were synthesized into one consensus version, which was used for backward translation in stage 3. This backward translation was performed by two independent translators who were native English speakers, blinded to the original version, and with no formal training in the health sciences. In stage 4, the final version of the instructions was revised by a panel of experts, who were in charge of consolidating the instructions of the questionnaire and producing a prefinal version. In stage 5, this prefinal version was used with 30 individuals with HKOA, who expressed no questions when completing the AAQ. Therefore, no additional changes had to be made to the translated instructions. Communication with the authors of the original instrument was maintained throughout the entire process of translation. The Portuguese language instructions of the AAQ is available at the site myaaq.com.25

The WOMAC was originally developed to assess symptoms and physical disability in individuals with HKOA.26 It evaluates three dimensions - pain, stiffness, and physical function - with five, two, and seventeen questions, respectively. The Likert version of the WOMAC is rated on an ordinal scale of 0 to 4, with lower scores indicating lower levels of symptoms or physical disability. The version of the WOMAC used in this study has been cross-culturally adapted and validated to the Brazilian population.7

For the Timed Up and Go (TUG) test, the participants were instructed to stand up from a chair, walk a distance of three meters, at a self-selected and comfortable speed, turn around, walk back to the chair and sit down again.27 The test was performed with a walking aid, if necessary. The time to complete this task was measured in seconds. The first test was performed for familiarization and the time from the second test (after one-minute interval) was used for analysis. The TUG is one of the most feasible and reliable functional measures recommended by the Osteoarthritis Research Society International.28

The Short Physical Performance Battery (SPPB) assesses lower-limb function, standing balance, walking speed, and the ability to rise from a chair.29 First, the participants were asked to maintain their feet side-by-side, in semi-tandem, and tandem positions for 10 seconds each. Afterward, a 4-meter walk at the participant's normal pace was timed. Finally, the participants were asked to stand up from a chair and to sit down five times, as fast as possible. The participants were allowed to use their walking aids, if necessary, except in the standing balance test. The total score varied from 0 to 12, with higher scores indicating better lower-limb function. The first trial was performed for familiarization and the total score from the second trial (after three-minute interval) was used for analysis. The SPPB is widely used to assess physical performance in individuals with HKOA.30

ProceduresIn a home visit or an outpatient rheumatology clinic setting, the participants completed a sociodemographic and health history questionnaire. Afterward, they completed the AAQ and the WOMAC. Because many older Brazilians have a lower level of formal education the participant received help from the researcher to manage the computer and to read the instructions of the AAQ, if necessary. The WOMAC was interviewer-administered.7 Two trained physical therapists were responsible to collect the questionnaires’ data. To avoid contamination bias, the order of the questionnaires was changed for the second half of the participants.6 Anthropometrical data such as body mass and height were collected. Performance-based tests, TUG and SPPB, were administered by a single trained physical therapist to a subgroup of 71 participants who agreed in going to the physical therapy clinic of the Universidade Federal dos Vales do Jequitinhonha e Mucuri for testing. To assess test-retest reliability, the first 50 participants completed the AAQ twice with a one-week interval.

Data analysisThe characteristics of the participants were presented as means ± standard deviations (SD), and frequencies (proportions). The normality of numerical data distribution was evaluated using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, and the choice of the statistical test was done accordingly. As a prerequisite to perform the cross-cultural validity analysis, the AAQ was tested for unidimensionality through confirmatory factorial analysis. Model fit was evaluated by estimating the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA), the Tucker-Lewis Fit Index (TLI), and the Comparative Fit Index (CFI). RMSEA close to 0.06 or lower, TLI close to 0.95 or higher, or CFI close to 0.95 or higher indicate good model fit.31

To examine cross-cultural validity, an ordinal regression analysis was used to assess DIF across countries.18 As the AAQ was developed in the Netherlands, the Dutch sample was used for comparison.6 DIF was assessed for each AAQ item, separately. In the ordinal regression analyses, the dependent variable was the AAQ item score, and the independent variables were the group variables (two groups per analysis, with the Dutch as the reference group), the total AAQ score, and the interaction term between the group variables and the total AAQ score. First, the non-uniform DIF was tested. A pseudo R-square change score according to Nagelkerke with a magnitude larger than 0.035 and a significant interaction term (p<0.001) between the total AAQ score and the group variable were considered as non-uniform DIF. If there was no non-uniform DIF, the uniform DIF was tested. Odds ratio (OR) of the group variable with a magnitude outside the interval 0.53–1.89 and a statistical significance with p<0.001 were used as criteria for uniform DIF. OR below 0.53 indicates that the individual from the country under study, with a similar total AAQ score as the Dutch individual, scores lower on the item. Thus, the execution of the activity by the individual from the country at issue seems to be more difficult than for the Dutch individual. Conversely, OR above 1.89 indicates that the individual from the other country scores higher on the item, and execution of the activity is less difficult than for the Dutch individual. Ordinal logistic regression analyses were adjusted for sex, age, height, weight, affected joint, and presence of hip or knee prosthesis.6 The impact of item(s) with DIF on the total score was determined by calculating the Spearman's rho coefficients between the AAQ score with and without the DIF item(s). A significant Spearman's rho coefficient with a magnitude higher than 0.95 was considered as no important impact of the DIF item(s) on the total AAQ score.6

To evaluate the construct validity of the AAQ, Spearman's rho coefficients were calculated between the AAQ score and the score obtained in each domain of the WOMAC, the SPPB score, and the TUG performance. To evaluate the influence of formal education in completing the AAQ, Spearman's rho coefficients were also calculated for estimating the association between the AAQ score and the WOMAC domains dividing the participants into three groups, considering the following: 0–3 years of schooling, 4–7 years of schooling, and ≥8 years of schooling.32 The following guidelines were adopted for interpreting the strength of association for the Spearman's correlation: 0.00–0.25 represented little or no relationship, 0.26–0.50 represented a fair relationship, 0.51–0.75 represented a moderate to good relationship, and higher than 0.75 represented a good to excellent relationship.33

To evaluate internal consistency and test-retest reliability of the AAQ, we calculated the Cronbach's alpha coefficient and the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC2,1), respectively. A Cronbach's alpha coefficient that approaches 0.90 is high and the scale can be considered reliable.23 ICC values higher than 0.90 indicate excellent reliability.33 The standard error of measurement (SEM) was calculated by multiplying the standard deviation of the AAQ score with the square root of 1 minus the ICC.33 Data were analyzed with the SPSS statistical package (version 22, Chicago, Illinois), and Mplus version 6.11.

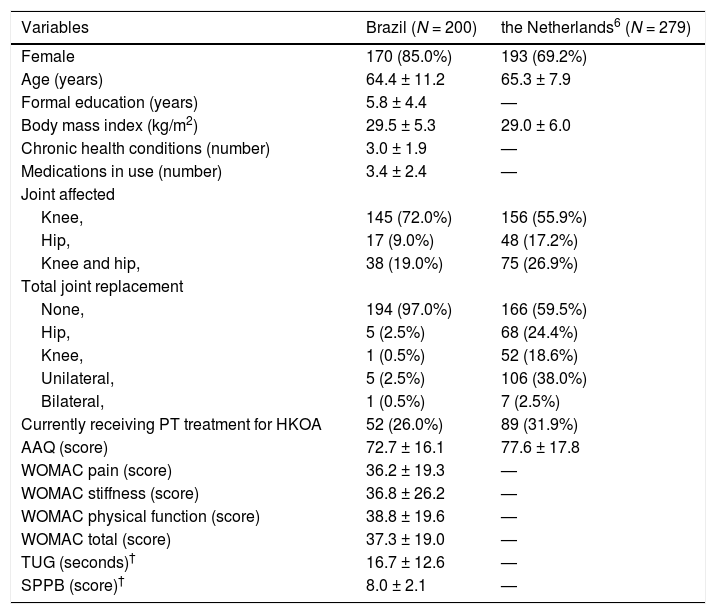

ResultsTwo hundred individuals with a clinical diagnosis of HKOA participated in the study. The majority of participants were female (85%) and had knee OA (72%). Only six participants had hip or knee joint replacement. The mean age of the participants was 64.4 ± 11.2 years, and the mean amount of education was 5.8 ± 4.4 years. The characteristics of the participants are described in Table 1.

Participants characteristics.

| Variables | Brazil (N = 200) | the Netherlands6 (N = 279) |

|---|---|---|

| Female | 170 (85.0%) | 193 (69.2%) |

| Age (years) | 64.4 ± 11.2 | 65.3 ± 7.9 |

| Formal education (years) | 5.8 ± 4.4 | — |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 29.5 ± 5.3 | 29.0 ± 6.0 |

| Chronic health conditions (number) | 3.0 ± 1.9 | — |

| Medications in use (number) | 3.4 ± 2.4 | — |

| Joint affected | ||

| Knee, | 145 (72.0%) | 156 (55.9%) |

| Hip, | 17 (9.0%) | 48 (17.2%) |

| Knee and hip, | 38 (19.0%) | 75 (26.9%) |

| Total joint replacement | ||

| None, | 194 (97.0%) | 166 (59.5%) |

| Hip, | 5 (2.5%) | 68 (24.4%) |

| Knee, | 1 (0.5%) | 52 (18.6%) |

| Unilateral, | 5 (2.5%) | 106 (38.0%) |

| Bilateral, | 1 (0.5%) | 7 (2.5%) |

| Currently receiving PT treatment for HKOA | 52 (26.0%) | 89 (31.9%) |

| AAQ (score) | 72.7 ± 16.1 | 77.6 ± 17.8 |

| WOMAC pain (score) | 36.2 ± 19.3 | — |

| WOMAC stiffness (score) | 36.8 ± 26.2 | — |

| WOMAC physical function (score) | 38.8 ± 19.6 | — |

| WOMAC total (score) | 37.3 ± 19.0 | — |

| TUG (seconds)† | 16.7 ± 12.6 | — |

| SPPB (score)† | 8.0 ± 2.1 | — |

Data are mean ± standard deviation or frequency (proportion).

Abbreviations: AAQ, Animated Activity Questionnaire; HKOA, hip/knee osteoarthritis; PT, physical therapy; SD, standard deviation; SPPB, Short Physical Performance Battery; TUG, Timed Up and Go; WOMAC, Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Index.

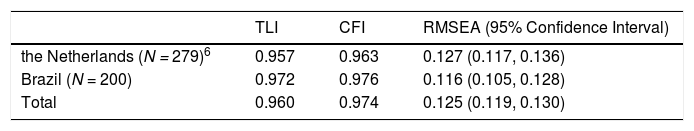

Confirmatory factorial analyses showed a good model fit for the unidimensionality of the AAQ for each country version and the total group of participants considering the TLI and CFI values, except for the RMSEA estimates (Table 2).

Confirmatory factor analyses of the AAQ.

| TLI | CFI | RMSEA (95% Confidence Interval) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| the Netherlands (N = 279)6 | 0.957 | 0.963 | 0.127 (0.117, 0.136) |

| Brazil (N = 200) | 0.972 | 0.976 | 0.116 (0.105, 0.128) |

| Total | 0.960 | 0.974 | 0.125 (0.119, 0.130) |

Abbreviations: AAQ, Animated Activity Questionnaire; CFI, Comparative Fit Index; RMSEA, Root Mean Square Error of Approximation; TLI, Tucker-Lewis Fit Index.

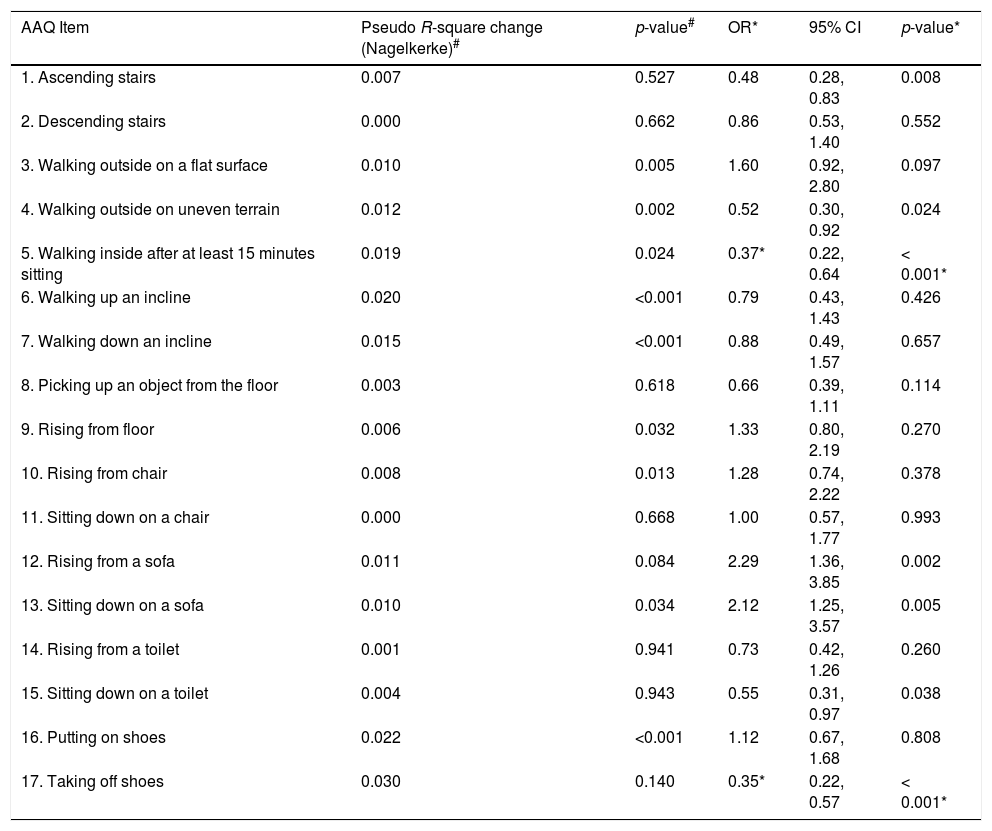

Cross-cultural validation analysis showed that none of the items met the criteria for non-uniform DIF (Table 3). Uniform DIF was found in items 5 and 17, walking inside after at least 15 min of sitting (OR 0.37) and taking off shoes (OR 0.35), respectively, showing that the Brazilian participants had more difficulty in executing these activities than the Dutch participants. Nevertheless, the Spearman's rho coefficient between the total AAQ score with and without the items 5 and 17 was 0.99 (95% CI=0.99 to 0.99).

Pseudo R-square change and Odds Ratio values for Non-uniform Differential Item Functioning (DIF), and Uniform DIF, respectively, in 17 items of the AAQ.

| AAQ Item | Pseudo R-square change (Nagelkerke)# | p-value# | OR* | 95% CI | p-value* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Ascending stairs | 0.007 | 0.527 | 0.48 | 0.28, 0.83 | 0.008 |

| 2. Descending stairs | 0.000 | 0.662 | 0.86 | 0.53, 1.40 | 0.552 |

| 3. Walking outside on a flat surface | 0.010 | 0.005 | 1.60 | 0.92, 2.80 | 0.097 |

| 4. Walking outside on uneven terrain | 0.012 | 0.002 | 0.52 | 0.30, 0.92 | 0.024 |

| 5. Walking inside after at least 15 minutes sitting | 0.019 | 0.024 | 0.37* | 0.22, 0.64 | < 0.001* |

| 6. Walking up an incline | 0.020 | <0.001 | 0.79 | 0.43, 1.43 | 0.426 |

| 7. Walking down an incline | 0.015 | <0.001 | 0.88 | 0.49, 1.57 | 0.657 |

| 8. Picking up an object from the floor | 0.003 | 0.618 | 0.66 | 0.39, 1.11 | 0.114 |

| 9. Rising from floor | 0.006 | 0.032 | 1.33 | 0.80, 2.19 | 0.270 |

| 10. Rising from chair | 0.008 | 0.013 | 1.28 | 0.74, 2.22 | 0.378 |

| 11. Sitting down on a chair | 0.000 | 0.668 | 1.00 | 0.57, 1.77 | 0.993 |

| 12. Rising from a sofa | 0.011 | 0.084 | 2.29 | 1.36, 3.85 | 0.002 |

| 13. Sitting down on a sofa | 0.010 | 0.034 | 2.12 | 1.25, 3.57 | 0.005 |

| 14. Rising from a toilet | 0.001 | 0.941 | 0.73 | 0.42, 1.26 | 0.260 |

| 15. Sitting down on a toilet | 0.004 | 0.943 | 0.55 | 0.31, 0.97 | 0.038 |

| 16. Putting on shoes | 0.022 | <0.001 | 1.12 | 0.67, 1.68 | 0.808 |

| 17. Taking off shoes | 0.030 | 0.140 | 0.35* | 0.22, 0.57 | < 0.001* |

Abbreviations: AAQ, Animated Activity Questionnaire; CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio.

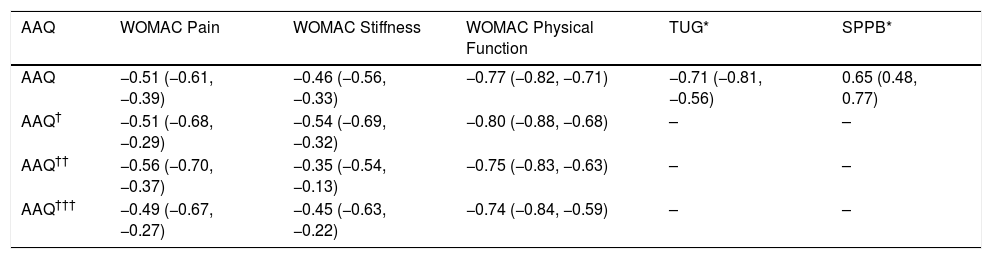

The AAQ showed a fair relationship with WOMAC stiffness, a moderate to good relationship with WOMAC pain, TUG, and SPPB, and a good to excellent relationship with WOMAC physical function. Considering the level of formal education, the correlations between the AAQ score and the three domains of the WOMAC were similar between the participants with 0–3, 4–7, and ≥8 years of schooling. The correlation coefficients are described in Table 4. Regarding reliability, the AAQ showed high internal consistency (Cronbach's alpha =0.94) and excellent test-retest reliability (ICC2,1 = 0.98; 95% CI=0.96 to 0.99).

Spearman rank order correlation coefficients (95% CI) between the total AAQ score, WOMAC domains, and performance-based tests in 200 participants with hip and knee osteoarthritis.

| AAQ | WOMAC Pain | WOMAC Stiffness | WOMAC Physical Function | TUG* | SPPB* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AAQ | −0.51 (−0.61, −0.39) | −0.46 (−0.56, −0.33) | −0.77 (−0.82, −0.71) | −0.71 (−0.81, −0.56) | 0.65 (0.48, 0.77) |

| AAQ† | −0.51 (−0.68, −0.29) | −0.54 (−0.69, −0.32) | −0.80 (−0.88, −0.68) | – | – |

| AAQ†† | −0.56 (−0.70, −0.37) | −0.35 (−0.54, −0.13) | −0.75 (−0.83, −0.63) | – | – |

| AAQ††† | −0.49 (−0.67, −0.27) | −0.45 (−0.63, −0.22) | −0.74 (−0.84, −0.59) | – | – |

Abbreviations: AAQ, Animated Activity Questionnaire; SPPB, Short Physical Performance Battery; TUG, Timed Up and Go; WOMAC, Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Index.

This was the first study to cross-culturally validate the AAQ in a developing country, characterized by lower per capita income, educational level, and life expectancy when compared to the countries in Europe where the AAQ was previously cross-culturally validated. Although assistance with language and/or navigation on the internet was necessary in some cases and the speed of the internet signal was found to be a barrier depending on the location, the AAQ was found to be a practical and inexpensive manner to assess activity limitations and showed good cross-cultural validity, construct validity, and reliability in Brazilian individuals with HKOA. Hence, we strongly recommend its use in research and clinical settings.

The cross-cultural validity presented in this study showed that the total score of the AAQ provided by the Brazilian participants might be comparable to the total score provided by the participants in the Netherlands and in the other six countries that showed a good cross-cultural validity when compared to the Netherlands results.6 However, a comparison of individual items might not be always possible between countries due to DIF in some items. Considering our results, the Brazilian participants showed a worse performance in two items of the AAQ, when comparing with the Dutch participants with similar total AAQ score.

Cross-validation studies are designed to provide comparable samples.22 Nevertheless, each country has its particularities. For example, 41% of the Dutch individuals had hip/knee prosthesis,6 compared to only 3% in the Brazilian sample. Although the DIF analysis was adjusted for sex, age, height, weight, affected joint, and presence of hip or knee prosthesis, factors that might influence the disability level, the higher rate of joint replacement in the Dutch sample might have contributed to their better performance in the items 5 and 17. It is known that the capacity to deliver and pay for these expensive procedures, rather than the severity level of osteoarthritis, is one of the determinants of the cross-country variations in the rate of hip/knee joint replacement.4 In addition, hip and knee joint replacement is considered the most effective intervention for severe osteoarthritis, reducing pain and disability, and restoring normal physical function.4

DIF between countries is usually due to language translation or cultural differences.6 Because the AAQ answers are based on videos, without language interference, it is expected that the DIF observed between countries is mainly due to cultural differences.6 Distinct national standards for sofas might also have contributed to explaining the DIF on item 5. Individuals from Denmark, Spain, and Norway also performed worse than the Dutch individuals in this item.6 However, a qualitative analysis of the AAQ is necessary to evaluate such hypotheses and explain the differences in the level of difficulty presented in items 5 and 17.

Regarding construct validity, the AAQ appeared to be unidimensional considering the TLI and CFI values, except for the RMSEA estimates. Probably, the difference in the number of response options between the items contributed to weakening the unidimensionality of the questionnaire.6 Moreover, the AAQ significantly correlated with the performance-based tests and all the WOMAC domains. The correlation between the AAQ and the physical function domain of the WOMAC was the highest. Other studies have also shown higher correlations of the AAQ with self-reported questionnaires than with performance-based tests.6,12,13 A possible explanation is that almost all the activities assessed by the AAQ, including complex activities such as ascending and descending stairs, picking an object from the floor, rising from and sitting down on a toilet, are assessed by the WOMAC physical function domain, whereas the TUG and the SPPB are limited to walking, rising from and sitting on a chair, and standing balance. In addition, the AAQ is a self-reported measure related to the perception of real-life performance,6 resembling the WOMAC and other self-reported measures, whereas the performance-based tests are capacity measures, performed in a standardized and controlled environment, which can significantly interfere in the person's ability.34 It is important to point out, that the Spearman's rho coefficients between the AAQ, the WOMAC physical function domain, and the performance-based tests varied from 0.65 to 0.77, demonstrating that the AAQ is a new construct placed on the continuum between self-reported measures and performance-based tests, as declared by Peter et al.6

According to the AAQ developers, completing the AAQ requires no comprehensive language understanding, except for directions and internet navigating. This makes the AAQ accessible for individuals with low literacy and non-native speakers.6 In contrast to the validation studies in the European countries, where the participants received an e-mail including an URL to the questionnaire online, in our study, the participants completed the questionnaire in the presence of the researchers and received help to read the instructions and/or to navigate through the questionnaire, if necessary. But participants played the videos as long as they wished and chose the video freely. Our results showed that low schooling did not compromise the validity of the AAQ if assistance is available.

Regarding reliability, a previous study evaluated internal consistency, test-retest reliability, and the SEM of the AAQ in six countries.15 The ICC2,1 for test-retest reliability was 0.93 when assessed for the total group, the Cronbach's alpha was 0.95, and the SEM was 4.9.15 Our study confirmed the excellent reliability of the instrument with an ICC2,1 of 0.98 and a Cronbach's alpha of 0.94 and showed a smaller SEM (2.25). Subgroup analysis from the previous study demonstrated higher SEM values in individuals with hip osteoarthritis and joint replacement when compared to individuals with knee osteoarthritis and without joint replacement,15 which could explain the better response stability observed in our study because of the relative frequency of participants with hip osteoarthritis and a joint replacement was lower in our sample.

A strength of this study is that we enrolled 200 individuals with HKOA, who varied in terms of sex, age, body mass index, joint affected, and exhibited a wide range of the AAQ scores. However, it is important to point out that the study was conducted in a Brazilian region with a low to medium Human Development Index and might not be representative of all Brazilian regions.

ConclusionThe AAQ showed adequate cross-cultural validity, construct validity, and reliability, which enables its use in clinical practice and research in Brazil and international/multicenter studies. Moreover, the level of formal education did not influence the construct validity of the AAQ.

The authors would like to thank the Policlínica Regional Dr. Lomelino Ramos Couto for the recruitment of participants. We also acknowledge the colleagues Cláudio Takashi Ikemura, Sven Peter Eriksson, Scott Alexander Kirkwood, Hellen Veloso Rocha Marinho, Rita de Cássia Corrêa Miguel, and Fabiane Ribeiro Ferreira for helping with the translation of the instructions of the AAQ for the Portuguese language. This study was supported by a grant from the Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico – CNPq (108978/2017-6).