Efficacious injury prevention programs exist, yet translation to practice in real-world settings is poor. Little is known about how women playing elite team ball-sports perceive and experience injury prevention programs in practice. Understanding the end-user's (athlete's) perspective is essential to improve program uptake and adherence.

ObjectiveTo explore the perspectives and experiences of injury prevention practices in athletes from the elite Australian Football League for Women (AFLW).

MethodsConvenience sample of 13 athletes from three AFLW clubs. Semi-structured interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim, analysed with a thematic analysis approach, and classified within the Socio-Ecological Model (SEM).

ResultsWomen playing elite Australian Football: (1) believe injury prevention programs have multiple aims and benefits, (2) perceive varying injury prevention practices between and within AFLW clubs, (3) believe injury prevention program adoption and implementation is complex and multi-factorial, and (4) think implementing injury prevention programs in the AFLW could be enhanced through education and resources. Mapping our results onto the SEM highlighted that athletes perceive multiple ecological levels (i.e. individual, interpersonal, community, and organizational) are involved in sports injury prevention.

ConclusionsMulti-level engagement strategies are required to enhance injury prevention program adoption and implementation and to maximise athlete adherence.

A national elite Australian Football League for Women (AFLW) was introduced in 2017. Women playing in this novel competition have a 6 times greater risk of serious knee injury compared to their male counterparts.42 Injury prevention exercise programs are efficacious in reducing knee injury risk in other team ball-sports.1–4 A recent meta-analysis of meta-analyses found women participating in these programs can reduce their risk of non-contact anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injury by 67%.1,5 Furthermore, risk of injury reduces with greater athlete program adherance.6–8 However, there is currently no knee-specific injury prevention program optimised for women playing elite Australian Football available.

Widespread adoption and implementation of efficacious injury prevention programs with high fidelity is challenging in real-world sporting settings.9,10 Varying intervention strategies are described in the literature as injury prevention such as: exercise programs, nutrition, protective equipment, load management, and screening.11 For clarity, in this manuscript these strategies are referred to as the encompassing term of injury prevention practices (IPP). To improve program adoption, implementation, and adherence, an understanding of end-user perceptions and behaviour using qualitative research methods is required.12 The importance of engaging end-users (i.e. athletes) in IPPs is recognised in frameworks to evaluate implementation success.13 However, the perspectives and experiences of IPPs amongst women playing elite team ball-sports has rarely been investigated.14 Giving athletes a voice to share their experiences, perceptions, and recommendations on IPPs is critical to improve the translation of sports injury prevention research into real-world settings.15

Sports injury prevention research is complex16 and there are many individual, sociocultural, and environmental factors, including individual behaviour, which affect program implementation.17,18 The Socio-Ecological Model (SEM) provides a framework to understand the interaction and influence of the factors (i.e. individual, socio-cultural, environmental) that impact human behaviour.19 The SEM has been applied in injury prevention research20–22 and is recommended as an approach to understand facilitators and barriers to injury prevention program implementation in sports medicine.21

The athlete's perspectives and experiences are crucial to ensuring contextually relevant, feasible IPPs are developed, adopted, implemented, and adhered to in the AFLW. Therefore, the aim of this study was to explore the perspectives and experiences of IPPs amongst women playing elite Australian Football to: (1) gain an understanding of current female athlete knowledge and experiences of IPPs in Australian Football, (2) explore the perceived barriers and facilitators to implementing IPPs in women's Australian Football, and (3) inform the development and implementation of future ACL IPPs in the AFLW.

MethodsThe La Trobe University Human Research and Ethics Committee approved this study [S17–217]. The Australian Football League (AFL) supported this study, and we have applied the consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ) checklist.23

Research designIndividual semi-structured interviews were conducted at the end of the 2018 AFLW season to explore the perspectives and experiences of IPPs amongst women playing elite Australian Football. Interviews were audio-recorded, transcribed verbatim, and analysed using a thematic analysis approach.24

ParticipantsA sample of convenience of female athletes were recruited from three Melbourne-based AFLW clubs (eight clubs were involved in the first two seasons of the national AFLW). The three recruited clubs had developed and embedded their own IPP informed by evidence-based programs25,26 into their pre-season and in-season training and match day preparation. To ensure maximum sample variation27 physical therapists identified potential interviewees based on: (1) one versus two years AFLW experience, (2) total years of Australian Football experience at any level categorised into <3 years, 3–5, >5 years, (3) other sporting experience at different competition levels. They were not directed to identify athlete's based on previous injury history. All potential participants provided written, informed consent before being interviewed.

Data collectionThirteen athletes were interviewed by a female academic and physical therapist (AB) who had previous experience in conducting semi-structured interviews and had no prior relationship with the participants. Interviewees provided sociodemographic information including their age, number of years playing elite Australian Football and other sporting experience, including level of attainment. The interview guide was developed by the study authors (AB, AM, KC), who have clinical and research experience in sports injury prevention. The interview guide was broad and flexible to probe athletes about their perceptions, experiences, and recommendations for IPPs. Where participants expanded on responses that covered multiple questions, the interviewer omitted some questions from the interview guide. Prompts or re-wording of questions were used if a participant had difficulty generating a response. Interviews were conducted around end of season musculoskeletal screening and exit interviews, five to 10 days after the final competitive game of the 2018 AFLW season. The interviews averaged 15 min (range, 9–26 min) and no new interviews were conducted when data saturation (i.e. no new ideas generated) was reached.

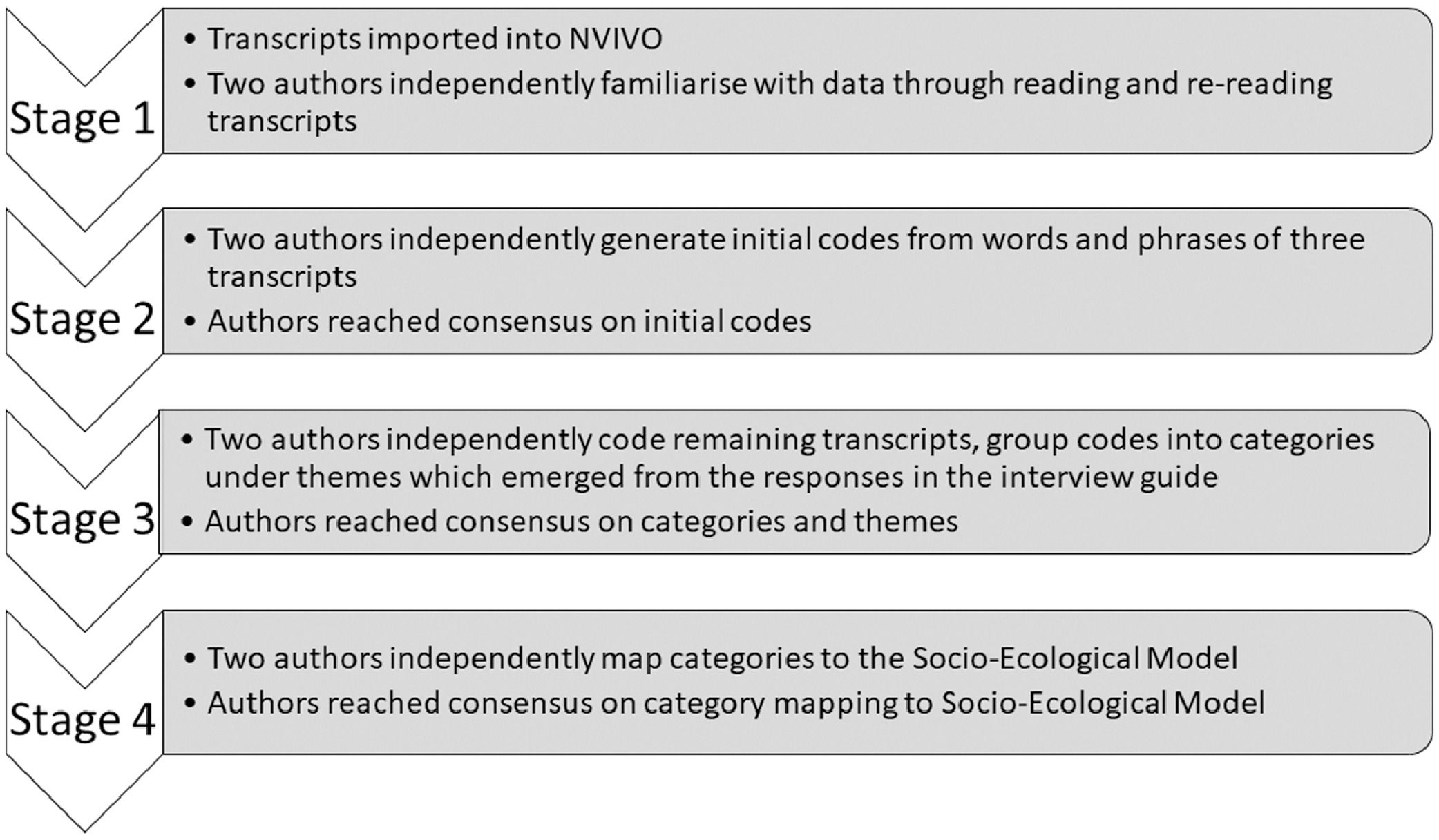

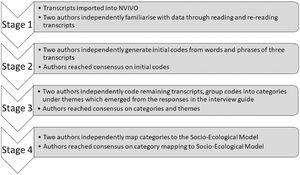

Data analysisAudio-recorded interviews were transcribed verbatim by an independent professional transcription service. Transcripts were imported into NVivo qualitative data analysis software (QSR International Pty Ltd, Victoria, Australia, Version 12.6 2019).

Qualitative thematic analysis using an inductive approach was undertaken to address the limited and fragmented knowledge in this area.24,28 Two researchers (AB, AM) read and re-read each transcript to immerse themselves in, and make sense of the data (Fig. 1). Codes were generated from words and phrases spoken by the participants. Both researchers independently organised the data of three transcripts through open coding and creating categories. Rich, thick descriptions were extracted to substantiate the degree of fit with the categories and to facilitate transferability to other contexts.29 Differences in coding and categories were discussed and the original data were re-read until consensus was reached. The authors independently coded and categorised the remaining transcripts before grouping under themes that emerged from the player's responses to the interview guide (e.g. purpose, barriers, facilitators, improvements). New categories emerged as the researchers moved back and forth between transcripts and analysis. Once themes and categories were finalised, two researchers (AB, AM) independently mapped each category to the relevant level of the SEM and consensus was reached.

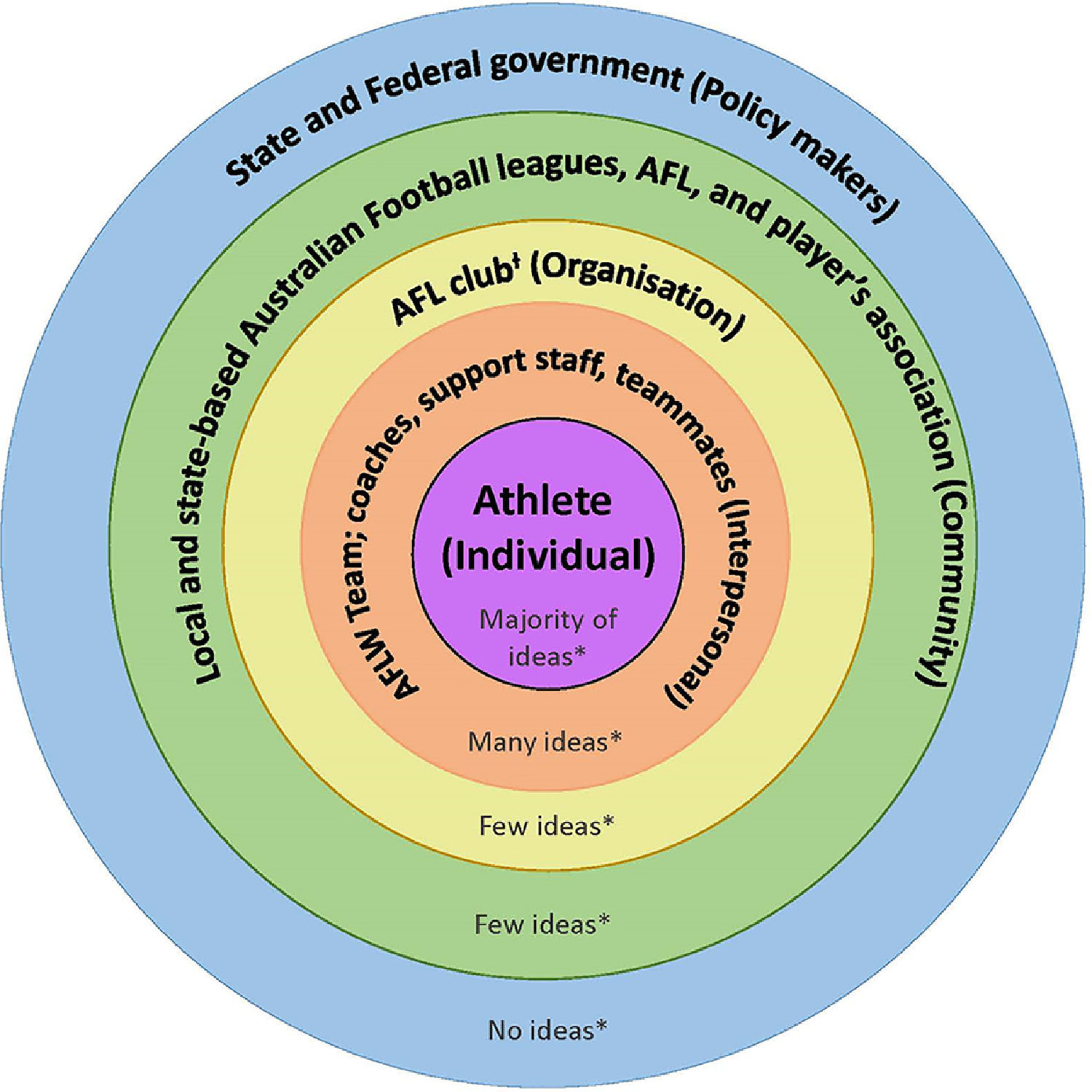

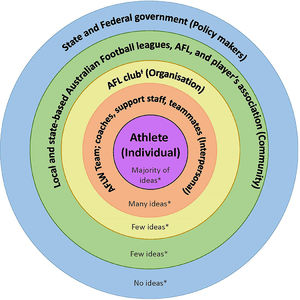

ResultsAthletes were on average 25 years of age (range 19–31), played an average of 1.7 AFLW seasons (range 1–2), with 2 to 15 years of AF experience (mean 8.2). All athletes had played a sport other than Australian Football. Three played in another sport at an elite level (two team-sport, one individual sport), and five athletes played team-sport at any other level. Two athletes reported a history of lower limb injury in the previous 12 months, which resulted in missing two games. One athlete reported previous ACL reconstruction. Perceived time dedicated to IPPs per training session ranged from 10 to 135 min (Club 1 30–80 mins, Club 2 15–50 mins, Club 3, 10–130 mins). This section describes each of the four key themes that emerged from the 13 interviews conducted using quotes from the interviews to illustrate that theme and the relationship of each theme to the SEM (Fig. 2).

The Socio-Ecological Model (SEM) applicable to elite female Australian Football (AF) players (adapted from Bogardus et al., 2019) *specific ideas generated for each level of the SEM can be found in Tables 1–4. ¿ Each Australian Football League club includes professional men's and women's Australian Football League teams, and men's and women's state league teams.

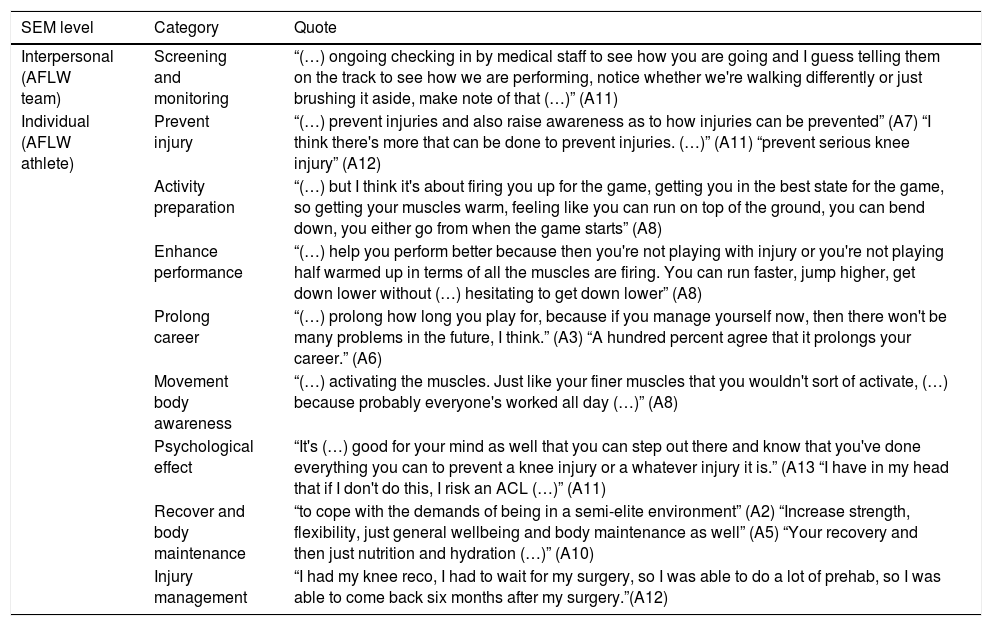

All athletes believed IPPs could minimise injury risk (Table 1). Specifically, they were aware that women playing Australian Football had a greater risk of knee injury and a lower risk of soft tissue injuries such as hamstring and groin injuries, compared to men. IPPs were perceived to have immediate benefits (e.g. enhance performance, activity preparation), but could also prolong their elite sporting career. Athletes believed their coaches and medical team played an important role in the successful implementation of IPPs.

Theme 1: IPPs minimise injury risk and enhance athletic performance and longevity.

In the quotes, (…) is used when the quotes have been shortened. SEM = Socio-Ecological Model.AFLW = Australian Football League for Women

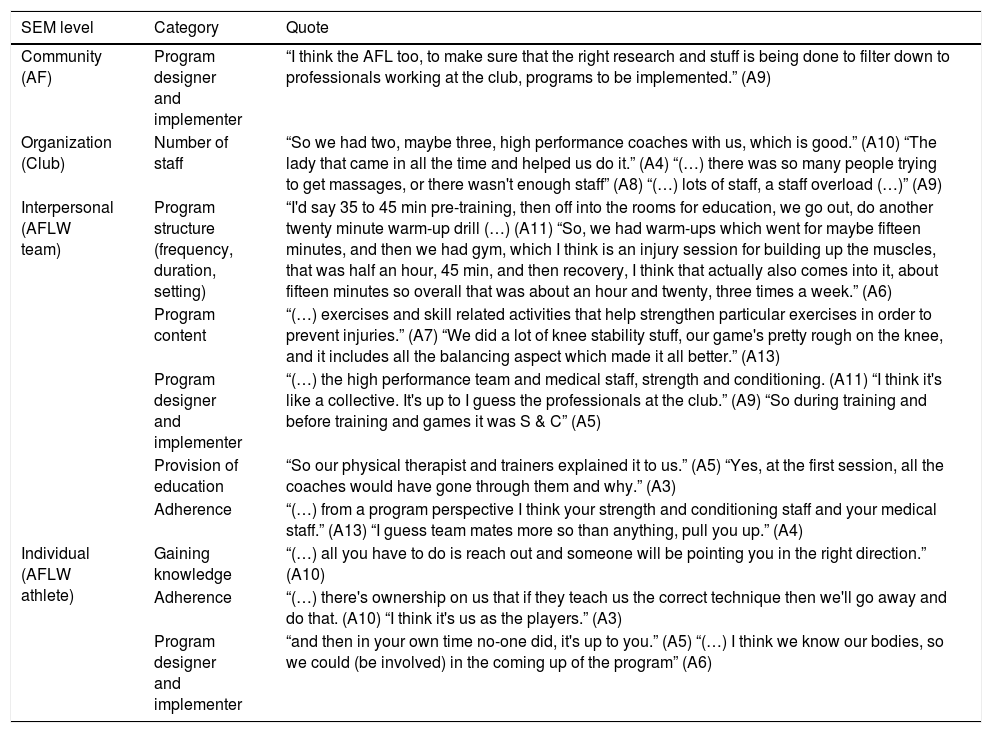

All athletes stated that they participated in IPPs during most training sessions and games (Table 2). Injury prevention activities were scheduled at the start of group training, but also included individual pre-training preparation time. IPPs that were described included: sport- and/or individual-specific exercises to: improve strength, muscle activation, muscle length, range of motion, movement awareness, activity preparation, and recovery techniques. Exercises were performed in the club rooms and/or on-field. Athletes who perceived resistance training and/or recovery strategies were components of IPPs also reported the gym and ice baths as locations for delivery. Athletes stated that they received education, however perceptions varied within clubs.

Theme 2. Perceptions of injury prevention practices vary.

In the quotes, (…) is used when the quotes have been shortened. SEM = Socio-Ecological Model.AFLW = Australian Football League for Women

“Yeah, definitely.” (A8) “So our physical therapist and trainers explained it to us.” (A5) “It was probably pretty brief, at the start, before we did the program, before the season. We were just made aware that we'd all be doing it.” (A7) “No.” (A6)

Club 2“Obviously it was delivered” (A2) “Yes, at the first session, all the coaches would have gone through them and why.” (A3) “Not too much. It was just I guess a brief rundown of the potential injuries and these are some ways to manage it. There was no sort of specific details.” (A1) “I can't even remember (…) Somebody talked about something.” (A4)

Club 3“(…) yes, constantly.” (A9) “(…) had a sort of a meeting with us but I feel like that's something they can improve” (A10) “Not too much” (A11), “ (…) I don't think we've gotten any, like I can't remember a presentation or anything explaining everything (…)” (A13) “None” (A12)

All athletes believed the design and delivery of IPPs was a group effort that included the physical therapist, strength and conditioning and high-performance coaches, and medical staff. Although athletes were not involved in designing current IPPs, they felt they could play a part, “(…) I think we know our bodies, so we could (be involved) in the coming up of the program” (A6). Athletes believed that IPP adherence was the responsibility of themselves, coaches, and teammates.

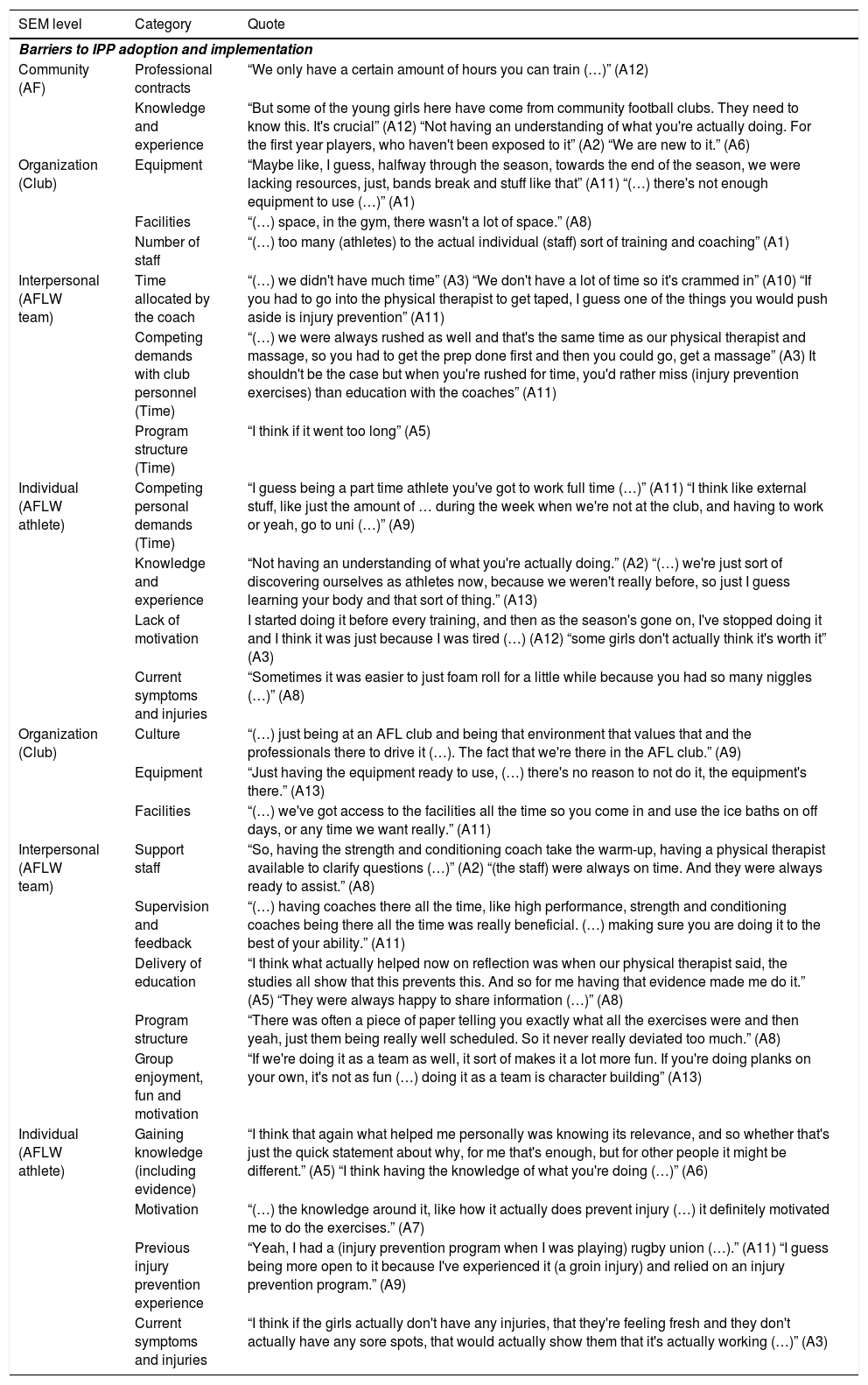

Theme 3. IPP adoption and implementation is complex and multi-factorialAthletes recognised many barriers and facilitators to IPP adoption and implementation across multiple SEM levels (individual, interpersonal, organization, community). Some categories were evident as both facilitators and barriers. For example, lack of athlete injury prevention knowledge was recognised as a barrier and acquiring knowledge was a facilitator that could have motivated athletes to adhere to IPPs (Table 3). Knowledge was recognised as a barrier to the individual, likely to be influenced by competing demands and a lack of time at the individual, interpersonal, and organizational level. Ultimately, knowledge (or lack thereof) was impacted by professional contracts that limited the time athletes could train and the financial reimbursement they would receive. This meant that athletes often worked full-time jobs, and/or studied, minimising the time and energy they could devote to their AFLW careers. It was clear that although athletes had good intentions to adhere to IPPs, the program structure, and a lack of previous football experience amongst some athletes meant that football-specific skills and meetings with coaches to improve their football performance were prioritized over IPPs. Supervision and individualised feedback on technique facilitated adherence, as did allocating training time to IPPs in a motivating and supported team environment.

Theme 3: IPP adoption and implementation is complex and multifactorial.

In the quotes, (…) is used when the quotes have been shortened. SEM, Socio-ecological model.AFLW = Australian Football League for WomenIPP = Injury Prevention ProgramAF = Australian Football

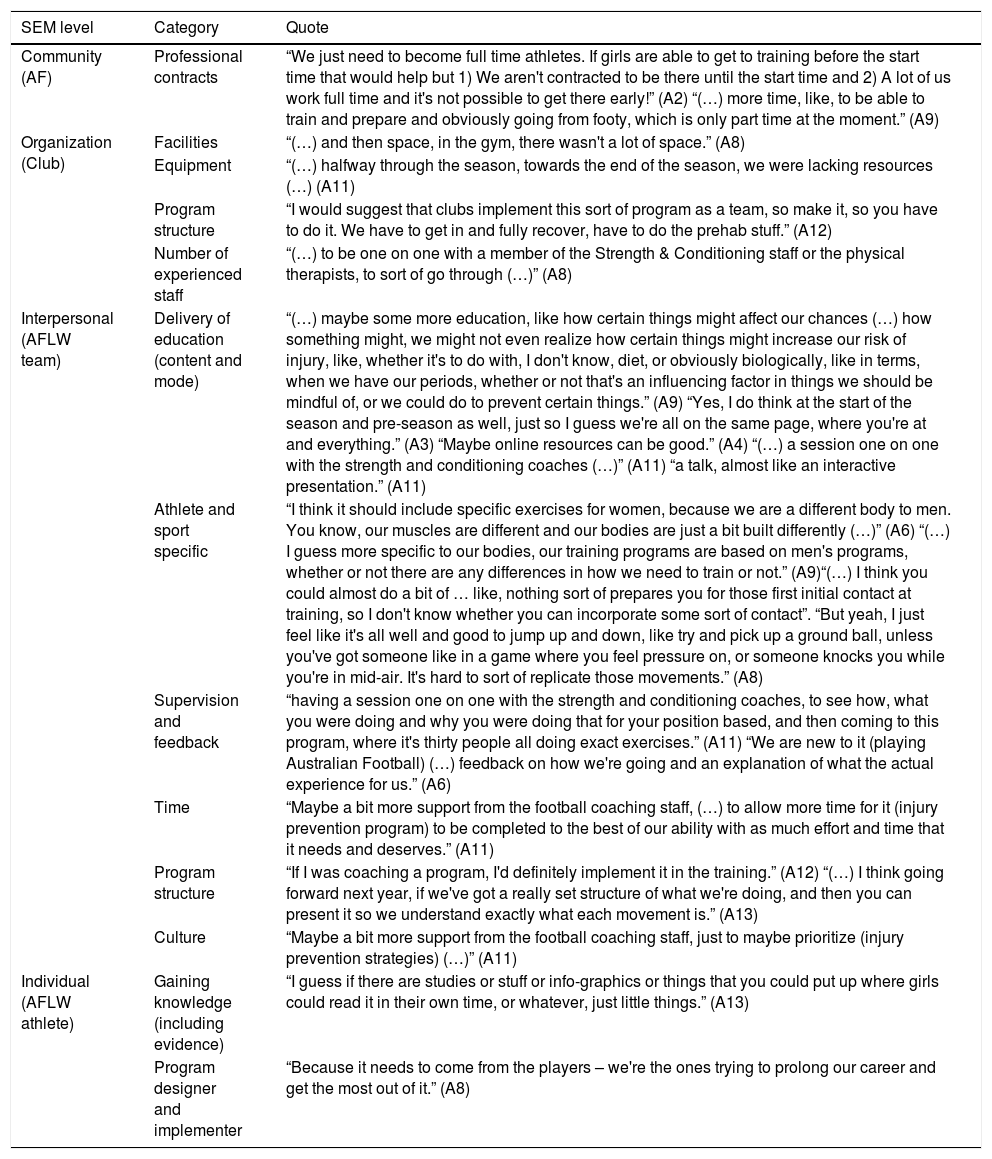

Athletes suggested IPP implementation strategies across all SEM levels except policy-makers (Table 4,Fig. 2), with some strategies relevant across multiple levels. For example, athletes identified a need to gain knowledge about injury prevention (individual) that could be provided by their coaches and medical team (interpersonal). Athletes wanted to know more about why injury prevention is important, what they can do to reduce their injury risk and individualised supervision and feedback around body movement awareness during exercise. Assuming a holistic approach to injury prevention, athletes suggested topics such as nutrition and menstrual cycles could also be relevant to reduce injury risk. Practical suggestions such as access to more equipment and space within facilities were identified as ways to improve IPP implementation.

Theme 4: Implementation could be enhanced through education and resources, including support staff.

In the quotes, (…) is used when the quotes have been shortened. SEM = Socio-Ecological Model.AFLW = Australian Football League for Women

Adult women playing elite Australian Football: (1) believe IPPs have multiple aims and benefits, (2) perceive varying IPPs between and within AFLW clubs, (3) believe IPP adoption and implementation is complex and multi-factorial, and (4) think implementing IPPs could be enhanced through education and resources, including support staff. Mapping our findings to the SEM highlighted the multiple levels that athletes perceive they are involved in sports injury prevention (Fig. 2). This suggests the need to develop multi-level targeted engagement strategies to support IPP implementation and athlete adherence emphasising the perspectives of the end-users and benefiters of these practices.

Women playing elite Australian Football value IPPs. Consistent with female Olympic athletes, professional male soccer players, and their physical therapists and coaches,30,31 AFLW athletes believe IPPs can reduce injury risk. They also perceive additional program benefits including physical and mental preparation for activity, performance enhancement, career longevity, recovery, and body awareness.

Coaches of female soccer players perceive IPPs enhance performance,32 and coach adoption and athlete adherence could be improved by changing how these programs are ‘sold’.33 Our findings highlight the need to ‘sell’ IPPs differently to different intended users (e.g. coaches versus players) and at different levels of the SEM (i.e. individual versus organisation). Despite preliminary evidence that sport-specific IPPs may improve athletic performance,33,354 the benefits in the AFLW are unknown. Interestingly, no athletes reported interpersonal or organisational level benefits of IPPs such as improved team success with less injuries.35 This may reflect that athletes perceive different IPP barriers and facilitators than staff members.31 Therefore, integrating all stakeholders’ perspectives when planning and implementing sports IPPs is required to increase adoption of these practices.

Elite AFLW players’ injury prevention experiences vary between and within clubs. They believed a collective group of professionals was responsible for IPP design and that athletes could contribute, yet none reported involvement in current program design (Table 3). Varying perspectives of experiences with program content were reported. We expected variation in program duration between teams but not the considerable variation in athlete perception of program duration within teams. This may be explained by the variation in players’ perceived knowledge, confidence, and understanding of what constituted injury prevention. Clearly, an opportunity exists for IPP education at the club and athlete level, and to engage athletes in co-creating programs.43 Giving athletes a voice in practices they are asked to adhere to may increase ownership and motivation, ultimately leading to greater adherence and injury risk reduction benefits.

Knowledge, or the lack thereof, was identified as both a facilitator and barrier to IPP adoption and implementation. The varied interpretation of injury prevention education experiences suggests that using different presentation methods tailored to the individual athlete's needs may be more effective. Interviewees wanted to know what, why and how IPPs are important. They also suggested developing organisation and community level resources including: infographics, videos, and mandatory education presentations like those they receive on other topics. Athletes suggested players could take greater personal responsibility for adopting IPPs. Education on the value of IPPs and providing support to individual players to own them could facilitate IPP adherence. However, increasing injury prevention knowledge will not automatically translate to changed behaviour,36 and success will depend on applying a complex-systems approach with strategies at multiple levels (individual, socio-cultural, environmental).37

Sex-, sport-, and athlete-specific IPPs are desired; but the adoption and implementation of these are complex and multifactorial. There is little evidence that the perspectives and experiences of IPPs in female, elite athletes have been explored and addressed when designing and implementing IPPs. This may contribute to the low program adherence in the real-world.14 Our findings suggest that AFLW athletes face many psychological, social, and contextual challenges in adopting IPPs which may contribute to increasing their injury risk. This supports previous research, where athletes perceive multi-level interactional factors that influence IPP implementation.30 Specifically, athletes identified challenges of playing in a semi-professional environment requiring juggling competing demands of work, football training, skill development, and commuting. To be successful elite Australian Football athletes, changes are required at many levels. Athletes need the opportunity to focus on developing their sport-specific skills, strength and conditioning, and mental well-being with additional resources required to succeed in an elite environment and reduced injury risk.38

Athlete-generated ideas concentrated around the individual and interpersonal level of the SEM with few suggestions mapped to the organization and community levels (Fig. 1). This may reflect that athletes perceive a narrow sphere of influence and they acknowledge the importance of the team environment on individual athlete behaviour. Nonetheless, athletes perceive the football governing body could play an important role in adopting and implementing IPPs developed specifically for them as end-users. The professional contracts currently offered to women playing elite Australian Football limit their capacity to be full-time athletes. The AFL Players’ Association is critical to advocating for enterprise bargaining agreements which allow female athletes the time, support, and opportunity to develop their football skills while still adhering to IPPs. Organization level changes to resources and culture were suggested by the athletes to facilitate IPP implementation. While not specifically identified by the players, the impact of existing imbalances in resource allocation between men and women on the implementation of IPPs requires further exploration. The athletes generally felt well supported at the club level. This may reflect the stark contrast from playing in sub-elite and community teams and clubs that often-lacked equipment and relied on volunteer staff. As previously identified, a system wide ecological approach to IPP implementation is required to create the change that the athletes have suggested.32,39

Methodological strengths and limitationsMember checking (interviewee verification of transcribed interviewees) was used to enhance data reliability.40 All interviewees had 14 days to verify that the data accurately reflected their interview. One athlete expanded on their responses. To ensure trustworthiness and rigour, two investigators (AB, AM) independently coded the data that were previously checked by interviewees for errors before consensus was reached. One researcher had met the participants and conducted the interviews (AB), and one had not (AM), providing different perspectives and building confidence in the study findings.41 Although we interviewed 13 AFLW athletes with a range of Australian Football (at any level) and AFLW experience, the concepts that have emerged from these data could be relevant to injury prevention efforts in similar settings e.g. women playing sub-elite or elite team ball-sports. To maximise convenience for the athletes, interviews were conducted around end-of-season musculoskeletal screening and club exit interviews. Therefore, some athletes may have been focused on other tasks and unable to provide detailed or well considered responses. However, athletes reviewed and revised their responses, thereby minimising this limitation and enhancing credibility of the findings.

ConclusionWomen playing elite Australian Football have perspectives and experiences that add considerable value to the development of IPPs. Their beliefs provide insight into strategies that might enhance player program adherence. Varied experiences and knowledge reveal the need to customise program content and education for different skill and literacy levels. Our findings support athletes as critical stakeholders who are well-positioned to inform IPP development. By doing so, they can identify meaningful and relevant opportunities at multiple ecological levels to enhance IPP implementation and effectiveness.

The authors would like to thank all participating athletes for their valuable participation in this study. This work was supported by the Australian Football League Research Board [2017]; La Trobe University Social Research Assistance Platform [2018]; and Andrea Mosler is supported by an NHMRC Early Career Fellowship (ECF 1156674). The funding bodies did not have any role in the design of the study or in collection, analysis, and interpretation of data, or in writing the manuscript.