To examine the interrater reliability and agreement of a pain mechanisms-based classification for patients with nonspecific neck pain (NSNP).

MethodsDesign – Observational, cross-sectional reliability study with a simultaneous examiner design. Setting: University hospital-based outpatient physical therapy clinic. Participants: A random sample of 48 patients, aged between 18 and 75 years old, with a primary complaint of neck pain was included. Interventions: Subjects underwent a standardized subjective and clinical examination, performed by 1 experienced physical therapist. Two assessors independently classified the participants’ NSNP on 3 main outcome measures. Main outcome measures: The Cohen kappa, percent agreement, and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated to determine the interrater reliability for (1) the predominant pain mechanism; (2) the predominant pain pattern; and (3) the predominant dysfunction pattern (DP).

ResultsThere was almost perfect agreement between the 2 physical therapists’ judgements on the predominant pain mechanism, kappa=.84 (95% CI, .65–1.00), p<.001. There was substantial agreement between the raters’ judgements on the predominant pain pattern and predominant DP with respectively kappa=.61 (95% CI, .42–.80); and kappa=.62 (95% CI, .44–.79), p<.001.

Conclusion(s)The proposed classification exhibits substantial to almost perfect interrater reliability. Further validity testing in larger neck pain populations is required before the information is used in clinical settings.

Clinical trial registration numberNCT03147508 (https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03147508).

Neck pain is a common problem and often becomes chronic.1,2 In the Global Burden of Disease 2010 study measured by years lived with disability, neck pain ranked fourth out of all 291 conditions studied.3–5 Among subjects with neck pain, 37% report persistent problems and 23% report a recurrent episode.6 Patients with neck pain account for up to 20% of all patients seen in outpatient physical therapy, which leaves physical therapists with the challenging task to make a reasoned diagnosis and to identify the important issues to be addressed during treatment.7

Neck complaints are usually not due to a serious disease or pathology, and often the exact cause for the pain remains unclear, a condition frequently referred to as ‘nonspecific neck pain’ (NSNP).8,9 In the absence of a precise pathological etiology,10,11 classifications based on pathoanatomy may not be the most effective method to guide treatment. Similar to low back pain (LBP), a classification based on information collected from the subjective and clinical examination may be useful in identifying subgroups and guiding treatment choices in NSNP patients.8,12

Defining the prevailing underlying neurophysiological mechanisms can help physical therapists in diagnosing and directing management goals.13–16 Dewitte et al.8 recently published classification criteria for NSNP, based on underlying pain patterns described by Gifford (i.e. the Mature Organism Model, including input, processing and output).15 In the approach of Dewitte et al.,8 clinicians classify the patients’ NSNP based on subjective and physical examination criteria into 1 of 5 dysfunction patterns (DPs) (i.e. articular DP, myofascial DP, neural DP, central/nociplastic DP, and sensorimotor control DP). The definitions and criteria on which clinicians decide to classify the patients’ NSNP are presented in detail elsewhere.8 These criteria show substantial overlap with the criteria of Smart et al.,17 by which clinicians determine pain mechanisms-based classifications of pain (i.e. nociceptive pain, neuropathic pain, and central pain).17 Both classification strategies can inform us about the neurophysiological mechanisms and are part of the parallel rounds of thought that characterize the essential reasoning process for a sound diagnosis.18 The DP-based classification holds the potential to guide treatment toward distinct clinical DPs with a high degree of face and content validity.19

To date, this classification has not yet been tested on measurement properties. Accepting reliability as a prerequisite for validity,20 the aim of this study was to investigate the interrater reliability and agreement of the clinical judgements associated with: (1) the pain mechanisms; (2) the pain patterns; and (3) the DPs driving the patients’ NSNP. The authors hypothesized that the proposed classification would show acceptable interrater reliability, as a preliminary step toward classification validation.

MethodsParticipants and settingThis cross-sectional reliability study was carried out at an outpatient physical therapy clinic of the Ghent University Hospital (Ghent, Belgium), between September 2017 and February 2018. Ethical approval to conduct this study was granted by the Ethics Committee of the Ghent University Hospital (Ghent, Belgium) in accordance with the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Subjects were referred by general practitioners and physical therapists from local hospitals, general practitioners’ clinics, and outpatient physical therapists’ clinics. The referring practitioners were informed on the inclusion and exclusion criteria, prior to the start of the study. All volunteers of any race or sex, aged between 18 and 75 years old, who experienced acute, subacute or chronic neck pain (±arm pain) were considered eligible for inclusion. Subjects were excluded if they were diagnosed with any serious pathology (i.e. cancer, metastasis, untreated fractures, history of diabetes or pathology of the (central) nervous system, non-musculoskeletal neck pain) that could compromise proper assessment or affect clinical reasoning. After the first screening for eligibility by the referring practitioners, subjects who expressed interest in participating were double-checked for eligibility by the researchers before enrolment in the study.

All participants were informed about the aims and procedure of the study and gave signed informed consent before testing. Forty-eight patients were recruited based on sample size calculations for detecting a kappa coefficient of .5 with a two-tailed test at an alpha level of .05 with 80% power.21 Based on the sample of 48 participants, a lower limit of .351 can be expected for the 95% CI of the .5 kappa coefficient.

The raters were 2 experienced physical therapists (first 2 authors), with both a postgraduate degree in Manual Therapy and respectively 13 and 6 years of clinical experience.

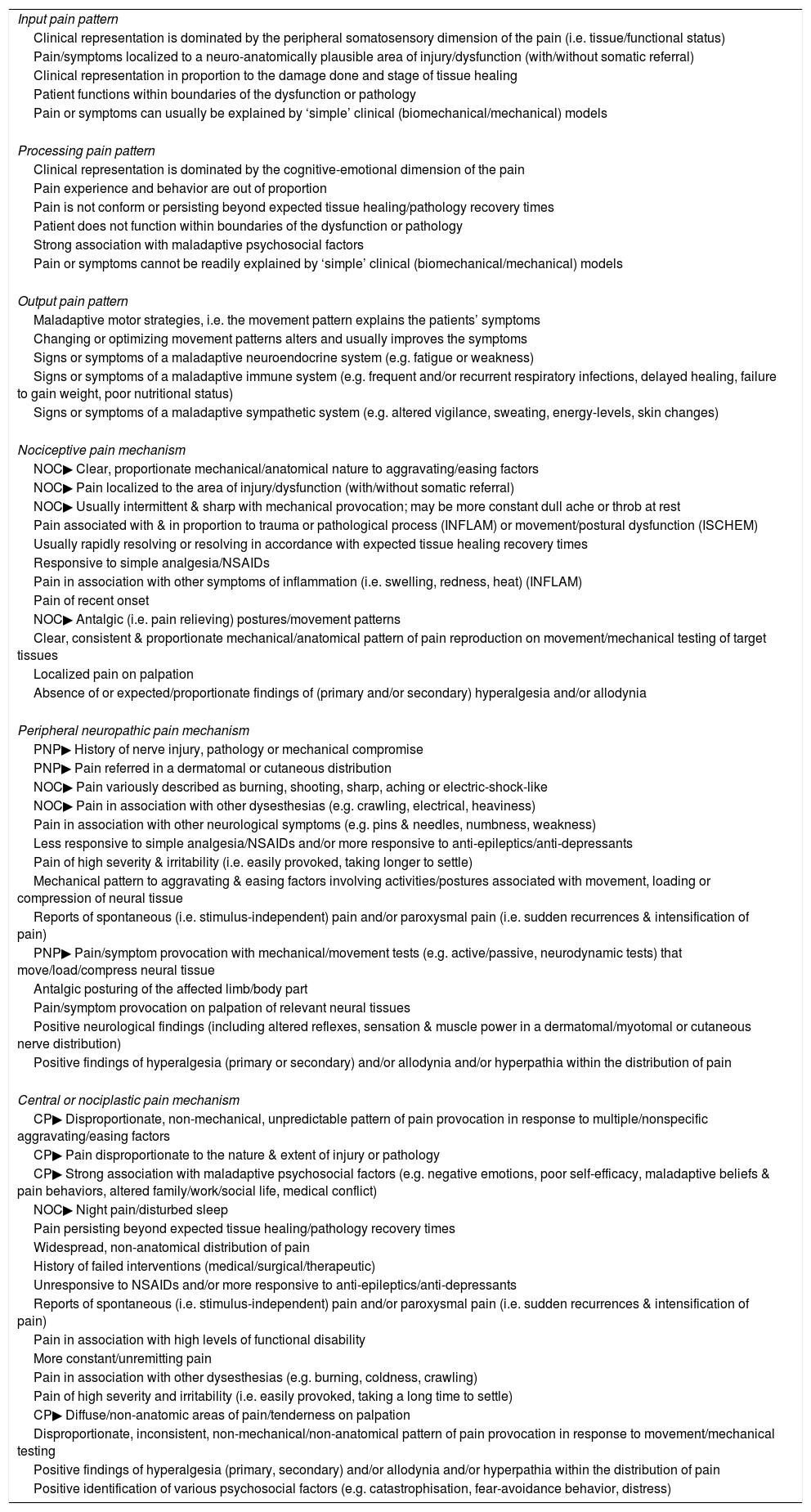

ProcedureA simultaneous examiner design was used to collect the data. Each patient was interviewed and examined by examiner 1, while examiner 2 observed the assessment to assure that both examiners had the same information. Several other reliability studies have used this approach to avoid variable responses or results due to repeated testing.20,22,23 The assessment was performed based on accepted clinical practice.24 The subjective examination consisted of questions related to demographic data; localization, intensity, quality, onset and evolution, circadian rhythm, provocation, and reduction of the pain; associated complaints (movement restrictions, headache, dizziness, nausea, other); medical diagnosis and history; results of technical examinations (medical imagery, blood tests, etc.), and questionnaires (Neck Disability Index and Central Sensitization Inventory); general health; red and yellow flags; restrictions in activities and participation; and medication and/or previous therapy. The physical examination included a postural and movement assessment, and was complemented with additional articular, myofascial, neurological, and/or sensorimotor control assessments. Following the assessment, both raters classified the patient's NSNP description on 3 outcome measures: (1) predominant pain mechanism (i.e. nociceptive, peripheral neuropathic or central/nociplastic pain)14,16,17,25; (2) predominant pain pattern (i.e. input, processing or output)15; and (3) predominant DP (i.e. articular DP, myofascial DP, neural DP, central/nociplastic DP, and sensorimotor control DP).8 The definitions of the DPs and the descriptions of the criteria on which the examiners decided to classify the patients’ NSNP are outlined in Tables 1–3.

| Input pain pattern |

| Clinical representation is dominated by the peripheral somatosensory dimension of the pain (i.e. tissue/functional status) |

| Pain/symptoms localized to a neuro-anatomically plausible area of injury/dysfunction (with/without somatic referral) |

| Clinical representation in proportion to the damage done and stage of tissue healing |

| Patient functions within boundaries of the dysfunction or pathology |

| Pain or symptoms can usually be explained by ‘simple’ clinical (biomechanical/mechanical) models |

| Processing pain pattern |

| Clinical representation is dominated by the cognitive-emotional dimension of the pain |

| Pain experience and behavior are out of proportion |

| Pain is not conform or persisting beyond expected tissue healing/pathology recovery times |

| Patient does not function within boundaries of the dysfunction or pathology |

| Strong association with maladaptive psychosocial factors |

| Pain or symptoms cannot be readily explained by ‘simple’ clinical (biomechanical/mechanical) models |

| Output pain pattern |

| Maladaptive motor strategies, i.e. the movement pattern explains the patients’ symptoms |

| Changing or optimizing movement patterns alters and usually improves the symptoms |

| Signs or symptoms of a maladaptive neuroendocrine system (e.g. fatigue or weakness) |

| Signs or symptoms of a maladaptive immune system (e.g. frequent and/or recurrent respiratory infections, delayed healing, failure to gain weight, poor nutritional status) |

| Signs or symptoms of a maladaptive sympathetic system (e.g. altered vigilance, sweating, energy-levels, skin changes) |

| Nociceptive pain mechanism |

| NOC▶ Clear, proportionate mechanical/anatomical nature to aggravating/easing factors |

| NOC▶ Pain localized to the area of injury/dysfunction (with/without somatic referral) |

| NOC▶ Usually intermittent & sharp with mechanical provocation; may be more constant dull ache or throb at rest |

| Pain associated with & in proportion to trauma or pathological process (INFLAM) or movement/postural dysfunction (ISCHEM) |

| Usually rapidly resolving or resolving in accordance with expected tissue healing recovery times |

| Responsive to simple analgesia/NSAIDs |

| Pain in association with other symptoms of inflammation (i.e. swelling, redness, heat) (INFLAM) |

| Pain of recent onset |

| NOC▶ Antalgic (i.e. pain relieving) postures/movement patterns |

| Clear, consistent & proportionate mechanical/anatomical pattern of pain reproduction on movement/mechanical testing of target tissues |

| Localized pain on palpation |

| Absence of or expected/proportionate findings of (primary and/or secondary) hyperalgesia and/or allodynia |

| Peripheral neuropathic pain mechanism |

| PNP▶ History of nerve injury, pathology or mechanical compromise |

| PNP▶ Pain referred in a dermatomal or cutaneous distribution |

| NOC▶ Pain variously described as burning, shooting, sharp, aching or electric-shock-like |

| NOC▶ Pain in association with other dysesthesias (e.g. crawling, electrical, heaviness) |

| Pain in association with other neurological symptoms (e.g. pins & needles, numbness, weakness) |

| Less responsive to simple analgesia/NSAIDs and/or more responsive to anti-epileptics/anti-depressants |

| Pain of high severity & irritability (i.e. easily provoked, taking longer to settle) |

| Mechanical pattern to aggravating & easing factors involving activities/postures associated with movement, loading or compression of neural tissue |

| Reports of spontaneous (i.e. stimulus-independent) pain and/or paroxysmal pain (i.e. sudden recurrences & intensification of pain) |

| PNP▶ Pain/symptom provocation with mechanical/movement tests (e.g. active/passive, neurodynamic tests) that move/load/compress neural tissue |

| Antalgic posturing of the affected limb/body part |

| Pain/symptom provocation on palpation of relevant neural tissues |

| Positive neurological findings (including altered reflexes, sensation & muscle power in a dermatomal/myotomal or cutaneous nerve distribution) |

| Positive findings of hyperalgesia (primary or secondary) and/or allodynia and/or hyperpathia within the distribution of pain |

| Central or nociplastic pain mechanism |

| CP▶ Disproportionate, non-mechanical, unpredictable pattern of pain provocation in response to multiple/nonspecific aggravating/easing factors |

| CP▶ Pain disproportionate to the nature & extent of injury or pathology |

| CP▶ Strong association with maladaptive psychosocial factors (e.g. negative emotions, poor self-efficacy, maladaptive beliefs & pain behaviors, altered family/work/social life, medical conflict) |

| NOC▶ Night pain/disturbed sleep |

| Pain persisting beyond expected tissue healing/pathology recovery times |

| Widespread, non-anatomical distribution of pain |

| History of failed interventions (medical/surgical/therapeutic) |

| Unresponsive to NSAIDs and/or more responsive to anti-epileptics/anti-depressants |

| Reports of spontaneous (i.e. stimulus-independent) pain and/or paroxysmal pain (i.e. sudden recurrences & intensification of pain) |

| Pain in association with high levels of functional disability |

| More constant/unremitting pain |

| Pain in association with other dysesthesias (e.g. burning, coldness, crawling) |

| Pain of high severity and irritability (i.e. easily provoked, taking a long time to settle) |

| CP▶ Diffuse/non-anatomic areas of pain/tenderness on palpation |

| Disproportionate, inconsistent, non-mechanical/non-anatomical pattern of pain provocation in response to movement/mechanical testing |

| Positive findings of hyperalgesia (primary, secondary) and/or allodynia and/or hyperpathia within the distribution of pain |

| Positive identification of various psychosocial factors (e.g. catastrophisation, fear-avoidance behavior, distress) |

Note: INFLAM, inflammatory nociceptive; ISCHEM, ischemic nociceptive; NSAIDs, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

Amended from Smart et al.17,41,42,57,58 Criteria are displayed per category as identified in the Delphi-study of Smart et al.17

NOC▶ Indicates the 7 criteria that were retained in the final predictive model for nociceptive pain.41,57

PNP▶ Indicates the 3 criteria that were retained in the final predictive model for peripheral neuropathic pain.57,58

CP▶ Indicates the 4 criteria that were retained in the final predictive model for central/nociplastic pain.42,57

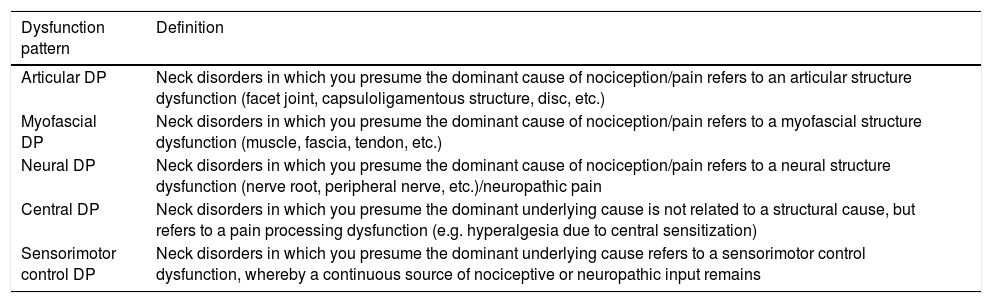

Definitions of the dysfunction patterns.a

| Dysfunction pattern | Definition |

|---|---|

| Articular DP | Neck disorders in which you presume the dominant cause of nociception/pain refers to an articular structure dysfunction (facet joint, capsuloligamentous structure, disc, etc.) |

| Myofascial DP | Neck disorders in which you presume the dominant cause of nociception/pain refers to a myofascial structure dysfunction (muscle, fascia, tendon, etc.) |

| Neural DP | Neck disorders in which you presume the dominant cause of nociception/pain refers to a neural structure dysfunction (nerve root, peripheral nerve, etc.)/neuropathic pain |

| Central DP | Neck disorders in which you presume the dominant underlying cause is not related to a structural cause, but refers to a pain processing dysfunction (e.g. hyperalgesia due to central sensitization) |

| Sensorimotor control DP | Neck disorders in which you presume the dominant underlying cause refers to a sensorimotor control dysfunction, whereby a continuous source of nociceptive or neuropathic input remains |

Note: DP, dysfunction pattern.

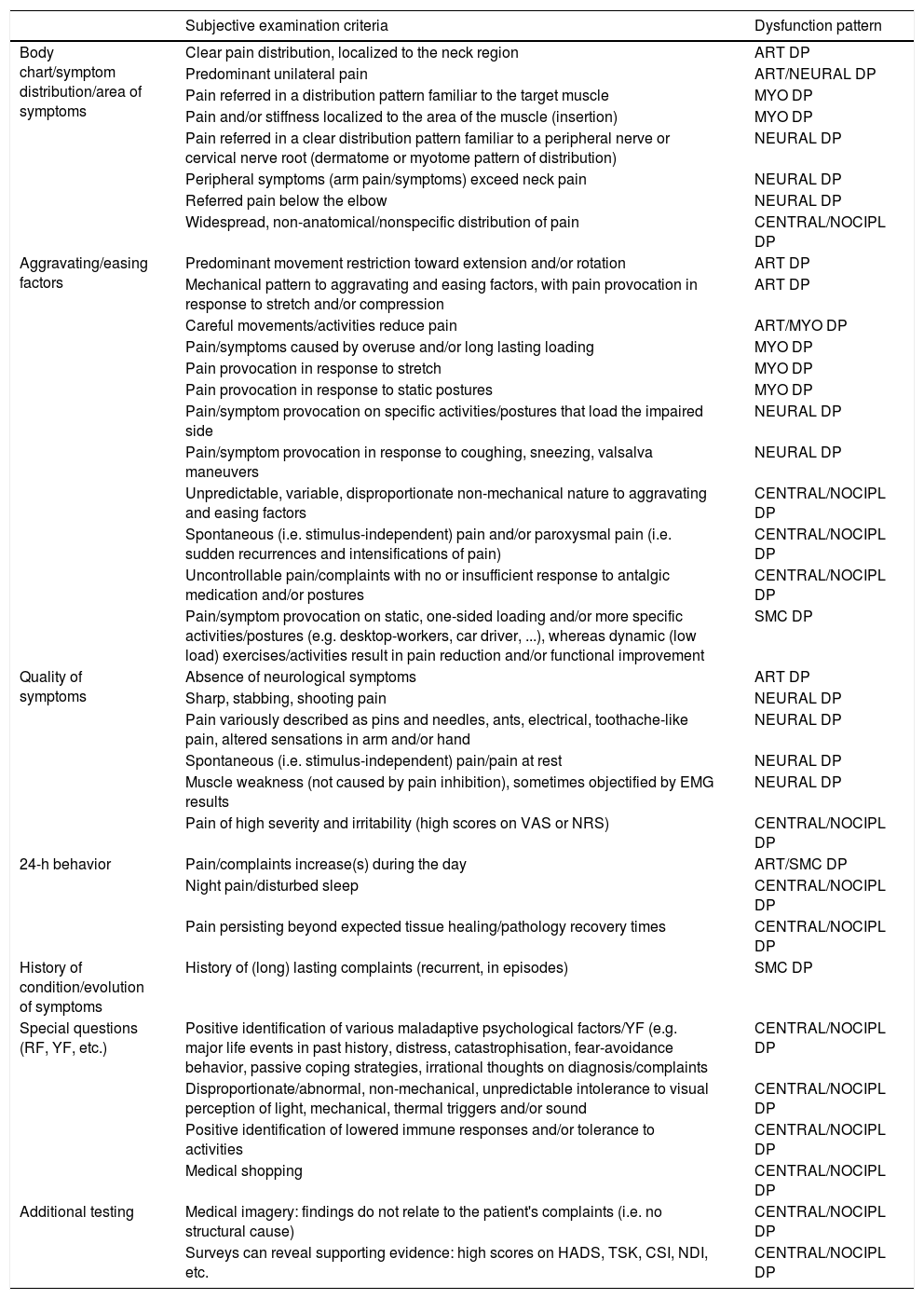

Subjective and physical examination criteria for the respective dysfunction patterns.a

| Subjective examination criteria | Dysfunction pattern | |

|---|---|---|

| Body chart/symptom distribution/area of symptoms | Clear pain distribution, localized to the neck region | ART DP |

| Predominant unilateral pain | ART/NEURAL DP | |

| Pain referred in a distribution pattern familiar to the target muscle | MYO DP | |

| Pain and/or stiffness localized to the area of the muscle (insertion) | MYO DP | |

| Pain referred in a clear distribution pattern familiar to a peripheral nerve or cervical nerve root (dermatome or myotome pattern of distribution) | NEURAL DP | |

| Peripheral symptoms (arm pain/symptoms) exceed neck pain | NEURAL DP | |

| Referred pain below the elbow | NEURAL DP | |

| Widespread, non-anatomical/nonspecific distribution of pain | CENTRAL/NOCIPL DP | |

| Aggravating/easing factors | Predominant movement restriction toward extension and/or rotation | ART DP |

| Mechanical pattern to aggravating and easing factors, with pain provocation in response to stretch and/or compression | ART DP | |

| Careful movements/activities reduce pain | ART/MYO DP | |

| Pain/symptoms caused by overuse and/or long lasting loading | MYO DP | |

| Pain provocation in response to stretch | MYO DP | |

| Pain provocation in response to static postures | MYO DP | |

| Pain/symptom provocation on specific activities/postures that load the impaired side | NEURAL DP | |

| Pain/symptom provocation in response to coughing, sneezing, valsalva maneuvers | NEURAL DP | |

| Unpredictable, variable, disproportionate non-mechanical nature to aggravating and easing factors | CENTRAL/NOCIPL DP | |

| Spontaneous (i.e. stimulus-independent) pain and/or paroxysmal pain (i.e. sudden recurrences and intensifications of pain) | CENTRAL/NOCIPL DP | |

| Uncontrollable pain/complaints with no or insufficient response to antalgic medication and/or postures | CENTRAL/NOCIPL DP | |

| Pain/symptom provocation on static, one-sided loading and/or more specific activities/postures (e.g. desktop-workers, car driver, ...), whereas dynamic (low load) exercises/activities result in pain reduction and/or functional improvement | SMC DP | |

| Quality of symptoms | Absence of neurological symptoms | ART DP |

| Sharp, stabbing, shooting pain | NEURAL DP | |

| Pain variously described as pins and needles, ants, electrical, toothache-like pain, altered sensations in arm and/or hand | NEURAL DP | |

| Spontaneous (i.e. stimulus-independent) pain/pain at rest | NEURAL DP | |

| Muscle weakness (not caused by pain inhibition), sometimes objectified by EMG results | NEURAL DP | |

| Pain of high severity and irritability (high scores on VAS or NRS) | CENTRAL/NOCIPL DP | |

| 24-h behavior | Pain/complaints increase(s) during the day | ART/SMC DP |

| Night pain/disturbed sleep | CENTRAL/NOCIPL DP | |

| Pain persisting beyond expected tissue healing/pathology recovery times | CENTRAL/NOCIPL DP | |

| History of condition/evolution of symptoms | History of (long) lasting complaints (recurrent, in episodes) | SMC DP |

| Special questions (RF, YF, etc.) | Positive identification of various maladaptive psychological factors/YF (e.g. major life events in past history, distress, catastrophisation, fear-avoidance behavior, passive coping strategies, irrational thoughts on diagnosis/complaints | CENTRAL/NOCIPL DP |

| Disproportionate/abnormal, non-mechanical, unpredictable intolerance to visual perception of light, mechanical, thermal triggers and/or sound | CENTRAL/NOCIPL DP | |

| Positive identification of lowered immune responses and/or tolerance to activities | CENTRAL/NOCIPL DP | |

| Medical shopping | CENTRAL/NOCIPL DP | |

| Additional testing | Medical imagery: findings do not relate to the patient's complaints (i.e. no structural cause) | CENTRAL/NOCIPL DP |

| Surveys can reveal supporting evidence: high scores on HADS, TSK, CSI, NDI, etc. | CENTRAL/NOCIPL DP |

| Physical examination criteria | |

|---|---|

| Observation | Antalgic posture |

| Insufficient posture, unable to maintain a corrected posture | |

| Placing the painful arm on top of the head results in pain relief (Bakody's sign) | |

| Palpation | Increased muscle tension |

| Presence of (active) myofascial trigger points/taught bands | |

| Hyperalgesia | |

| Allodynia (painful response to non-painful stimuli) | |

| Active/passive movement testing | Associated with unilateral compression and/or stretch pain |

| Provocation in response to combined movement testing (3D-extension/3D-flexion) | |

| Predominant movement restriction toward extension and/or rotation | |

| Restricted ROM on passive and active movement testing | |

| Relaxation of relevant myofascial structures does not result in an increased passive ROM | |

| Traction reduces pain/symptoms | |

| Active movement testing provokes symptoms and reveals ROM restrictions | |

| Impaired quality of movement | |

| Relaxation of relevant myofascial structures does result in an increased passive ROM | |

| Mechanical pattern to aggravating and easing factors, with pain provocation in response to stretch and/or compression | |

| Provocation of peripheral pain/symptoms in response to ipsilateral rotation, ipsilateral side bending and extension of the neck (positive Spurling's test) | |

| Variable findings in active movement assessment | |

| Muscular imbalance with increased activity of superficial/global neck muscles | |

| Pain/symptom provocation with repeated movement testing | |

| Myofascial assessment | Localized, unilateral increased muscle tension |

| Pain/symptom provocation/local twitch response on palpation of relevant myofascial structures (trigger point(s)) | |

| Pain/symptom provocation in response to stretch of relevant myofascial structures (positive muscle length tests) | |

| Reduced muscle power and/or endurance of impaired muscles | |

| Articular assessment | Intervertebral movement restriction at the impaired segment (aberrant end feel) |

| Pain/symptom provocation/muscle tension on palpation of relevant articular structures (positive UPA) | |

| No clear intervertebral movement restriction(s) | |

| Neurological assessment | Negative findings on neurological function and provocation testing |

| Positive neurological findings (i.e. altered deep-tendon reflexes, sensation and motor strength) | |

| Positive neurodynamic tests | |

| Pain/symptom provocation in response to palpation of the nerve | |

| Positive cluster of Rubinsteinb/Positive cluster of Wainnerc | |

| Positive slump test | |

| Absence of clear neurological findings | |

| Sensorimotor control | Muscular imbalance with impaired cervical and/or scapulothoracic neuromuscular control and/or proprioception |

| Other | Inconsistent and ambiguous findings/diagnostics that vary over sessions |

| Disproportionate/abnormal, reaction during and after the patient's assessment and/or treatment |

Notes: DP, dysfunction pattern; ART, articular; MYO, myofascial DP; NOCIPL, nociplastic; SMC, Sensorimotor control; RF, red flags; YF, yellow flags; EMG, electromyography; VAS, visual analogue scale; NRS, numeric rating scale; HADS, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scales; TSK, Tampa Scale for Kinesiophobia; CSI, Central Sensitization Inventory; NDI, Neck Disability Index; 3D, 3-dimensional; ROM, range of motion; UPA, unilateral posteroanterior provocation test.

Clinical criteria highlighted in bold are unique to the dysfunction pattern.

Positive cluster of Rubinstein (Rubinstein et al.59): positive Spurling's test, traction/neck distraction, and Valsalva maneuver are indicative of a cervical radiculopathy, while a negative upper-limb tension test is used to rule it out.

Positive cluster of Wainner (Wainner et al.33): positive Spurling's test, traction reduces irradiating symptoms, rotation ROM toward the painful side is restricted (less than 60° ROM), positive upper-limb tension test.

Both researchers had 6 years of previous experience with the proposed clinical reasoning model. Before participation, however, the raters studied an assessment manual with definitions and guidelines for the standardized assessment and thoroughly discussed the interpretation of all subjective and physical examination criteria. The assessment protocol was piloted in 2 ‘dummy trials’ to ascertain equal understanding of the diagnostic procedure. To ensure that the raters were blind to each other's judgements, both researchers independently registered the participants’ classification in separate databases, without knowing each other's decision.

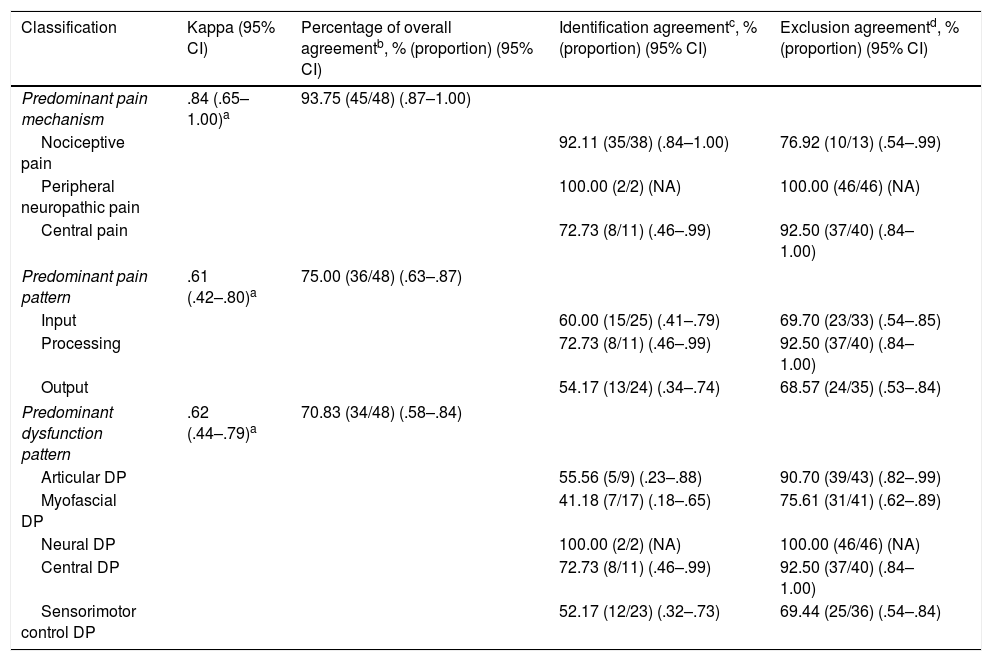

Data analysisThe data analysis was performed using RStudio for Windows version R 3_4_1 (RStudio, Boston, MA, USA). To assess interrater reliability of the classification, Cohen's kappa and percentage of overall agreement with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated. Percentage of overall agreement was defined as the percentage of cases in which both raters agreed on the condition being present in the total study population (n=48). To explore the nature of agreements in the physical therapists’ judgements, identification agreement and exclusion agreement were examined. Identification agreement was defined as the percentage of cases in which both raters agreed on the condition being present, in the subset of cases that were labeled by at least one rater as being present. Finally, exclusion agreement was defined as the percentage of cases in which both raters agreed on the condition being absent, in the subset of cases that were labeled by at least one rater as being absent.

Interpretations of kappa values were based on categories outlined by Landis and Koch.26 For the purpose of this study ‘clinically acceptable’ reliability was defined as kappa >.60 or in the absence of kappa, a percentage agreement of ≥80%.20,27,28

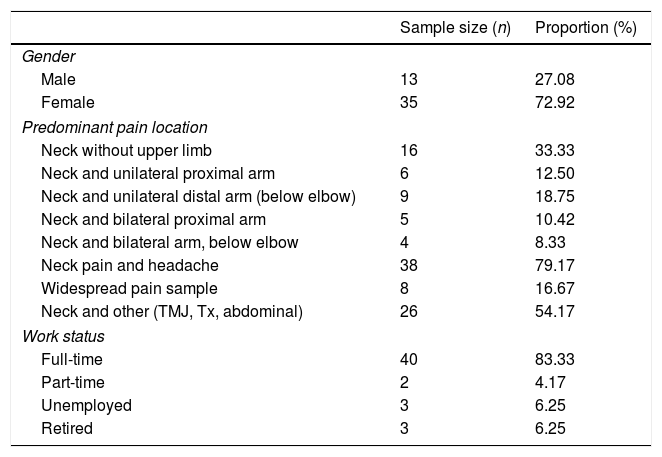

ResultsForty-eight patients with NSNP participated in this study. Patient characteristics are detailed in Table 4. There was almost perfect agreement between the 2 physical therapists’ judgements on the predominant pain mechanisms, kappa=.84 (95% CI, .65–1.00), p<.001. There was substantial agreement between the raters’ judgements on the predominant pain patterns and predominant DPs with respectively kappa=.61 (95% CI, .42 .80); and kappa=.62 (95% CI, .44–.79), p<.001. The percentages, proportions, and 95% CIs of the percentage of overall agreement, identification agreement, and exclusion agreement are displayed in Table 5. For example, in 92.11% (35 out of 38) of the cases both raters agreed on the predominant pain mechanism being nociceptive pain, in the subset of cases that were labeled by at least one rater as being nociceptive pain. Accordingly, in 76.92% (10 out of 13) of the cases both raters agreed on the predominant pain mechanism not being nociceptive pain, in the subset of cases that were labeled by at least one rater as not nociceptive pain.

Characteristics of the included subjects (n=48).

| Sample size (n) | Proportion (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 13 | 27.08 |

| Female | 35 | 72.92 |

| Predominant pain location | ||

| Neck without upper limb | 16 | 33.33 |

| Neck and unilateral proximal arm | 6 | 12.50 |

| Neck and unilateral distal arm (below elbow) | 9 | 18.75 |

| Neck and bilateral proximal arm | 5 | 10.42 |

| Neck and bilateral arm, below elbow | 4 | 8.33 |

| Neck pain and headache | 38 | 79.17 |

| Widespread pain sample | 8 | 16.67 |

| Neck and other (TMJ, Tx, abdominal) | 26 | 54.17 |

| Work status | ||

| Full-time | 40 | 83.33 |

| Part-time | 2 | 4.17 |

| Unemployed | 3 | 6.25 |

| Retired | 3 | 6.25 |

| Mean | Median | Range | IQR | SD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 36.52 | 30.50 | (19.00–65.00) | (24.00–49.00) | 13.90 |

| Height (cm) | 171.27 | 172.00 | (154.00–191.00) | (164.00–178.00) | 8.56 |

| Weight (kg) | 69.71 | 69.00 | (48.00–110.00) | (60.25–77.75) | 12.38 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 23.74 | 22.49 | (18.75–35.38) | (20.40–26.52) | 3.75 |

| Average symptom intensity (NRS) over previous 7 days | 3.92 | 4.00 | (1.00–8.00) | (2.00–5.00) | 1.74 |

| Worst symptom intensity (NRS) over previous 7 days | 6.13 | 7.00 | (1.00–10.00) | (5.00–8.00) | 1.89 |

| NDI score | 10.89 | 9.50 | (2.00–31.00) | (7.00–13.00) | 5.77 |

| CSI score | 34.57 | 34.00 | (8.00–68.00) | (26.00–41.00) | 13.79 |

| Duration of current episode (weeks) | 155.69 | 3.00 | (0.00–1404.00) | (0.29–260.00) | 294.87 |

Note: TMJ, temporomandibular joint complaints; Tx, musculoskeletal thoracic complaints; IQR, interquartile range; BMI, body mass index; NRS, numeric pain rating scale; NDI, Neck Disability Index; CSI, Central Sensitization Inventory.

Interrater reliability of the 3 main outcome measures in patients with nonspecific neck pain (n=48).

| Classification | Kappa (95% CI) | Percentage of overall agreementb, % (proportion) (95% CI) | Identification agreementc, % (proportion) (95% CI) | Exclusion agreementd, % (proportion) (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predominant pain mechanism | .84 (.65–1.00)a | 93.75 (45/48) (.87–1.00) | ||

| Nociceptive pain | 92.11 (35/38) (.84–1.00) | 76.92 (10/13) (.54–.99) | ||

| Peripheral neuropathic pain | 100.00 (2/2) (NA) | 100.00 (46/46) (NA) | ||

| Central pain | 72.73 (8/11) (.46–.99) | 92.50 (37/40) (.84–1.00) | ||

| Predominant pain pattern | .61 (.42–.80)a | 75.00 (36/48) (.63–.87) | ||

| Input | 60.00 (15/25) (.41–.79) | 69.70 (23/33) (.54–.85) | ||

| Processing | 72.73 (8/11) (.46–.99) | 92.50 (37/40) (.84–1.00) | ||

| Output | 54.17 (13/24) (.34–.74) | 68.57 (24/35) (.53–.84) | ||

| Predominant dysfunction pattern | .62 (.44–.79)a | 70.83 (34/48) (.58–.84) | ||

| Articular DP | 55.56 (5/9) (.23–.88) | 90.70 (39/43) (.82–.99) | ||

| Myofascial DP | 41.18 (7/17) (.18–.65) | 75.61 (31/41) (.62–.89) | ||

| Neural DP | 100.00 (2/2) (NA) | 100.00 (46/46) (NA) | ||

| Central DP | 72.73 (8/11) (.46–.99) | 92.50 (37/40) (.84–1.00) | ||

| Sensorimotor control DP | 52.17 (12/23) (.32–.73) | 69.44 (25/36) (.54–.84) | ||

Note: DP, dysfunction pattern; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval; NA, not applicable.

Percentage of overall agreement, percentage of cases in which both raters agreed on the condition being present in the total study population (n=48).

This is the first study to examine the interrater reliability and agreement of the clinical judgements associated with predominant pain mechanisms, pain patterns, and DPs in patients with NSNP. The interrater reliability of the prevailing pain pattern and DP was substantial. The classification into predominant pain mechanism showed almost perfect reliability. These findings provide preliminary evidence that the proposed classification has acceptable clinical reliability, as a step toward classification validation. The standardized assessment protocol, the fixed examiner, and the previous experience with the proposed classification all presumably contributed to the interrater reliability observed in this study.

To our knowledge, there are no previous studies available on interrater reliability of clinical judgements associated with predominant pain patterns, and DPs in patients with NSNP. Therefore, it is difficult to compare our findings to the existing literature. A number of articles have reported the reliability of various components of the subjective or physical examination for patients with neck pain.29–38 Surprisingly, only few studies have reported reliability of components of both the subjective and physical examination.29,33 Yet, obtaining a history can influence reliability of the physical examination.32

Predominant pain mechanismConsistent with a previous study investigating the reliability of clinical judgements associated with the predominant pain mechanisms in LBP patients,20 the current study found clinically acceptable reliability for this outcome measure.

Studying the sub-categories, judgments related to the peripheral neuropathic pain (PNP) category seemed to have perfect agreement. As Cohen stated, differentiating PNP from nociceptive pain is probably the most important clinical distinction to make.39 Yet, this must be interpreted with caution, as there were only 2 out of 48 subjects identified with a dominance of PNP (as mentioned in Table 5). This high degree of clustering patients in non-PNP categories has most likely inflated the kappa value for the PNP category. Other reliability studies exploring the identification of clinical indicators for PNP (in LBP patients) found only fair to moderate levels of interrater reliability.20,40

The examiners in this study seemed to identify patients’ pain states more reliable as predominant nociceptive as compared to the exclusion of predominant nociceptive pain. The opposite was found for the central/nociplastic pain state. This could be supported by the fact that a dominance of nociceptive pain typically has clear criteria on which physical therapists base their judgements (e.g. ‘pain localized to the area of injury/dysfunction’, ‘clear, proportionate mechanical/anatomical nature to aggravating and easing factors’, ‘pain is usually intermittent and sharp with movement/mechanical provocation’, etc.).41 On the other hand, a predominant central/nociplastic pain mechanism is usually characterized by the lack of a consistent clinical pattern (e.g. ‘disproportionate, non-mechanical, unpredictable pattern of pain provocation in response to multiple/nonspecific aggravating/easing factors’).42 Caution is warranted when interpreting these assumptions, since the indicators for pain mechanisms in LBP patients may not generally apply to patients with neck pain. Nevertheless, the ‘central/nociplastic’ features discernible in NSNP patients most commonly agreed upon in the Delphi-survey by Dewitte et al.8 were similar to those identified in LBP patients by Smart et al.42

Predominant pain pattern and dysfunction patternThe pain pattern classification and DP classification show comparable, clinically acceptable kappa values. The agreement levels seem to reveal a trend in that exclusion agreements are higher than identification agreements. From a probability point of view, it seems evident that the exclusion of a condition by 2 raters yields better conformity, compared to the identification of a condition. For the identification of the predominant pain pattern, both raters had to agree on 1 out of 3 categories (i.e. input, processing or output), resulting in a 3/9 chance to agree. On the other hand, for the exclusion agreement they had 4/9 chances to agree on the absence of the prevailing pain pattern. Analogue reflections apply to the predominant DP classification. The 2 physical therapists had only 5/25 chances to agree on the identified DP, in contrast to the 16/25 chances to agree on the absence of the remaining DPs.

It is important that a dominance of central/nociplastic DP/processing mechanism, underlying a patient's NSNP, can be ruled out, since these patients require a different approach.43 Because the processing pain pattern and central/nociplastic DP are defined in a similar way, they both attained identical, clinically acceptable agreement levels.

The input and output pain patterns did not reach the percentage agreement level of ≥80% for clinical acceptance, neither did the myofascial and sensorimotor control DPs. Possibly this could be explained by the interrelationship between input and output patterns, and the considerable overlap in clinical indicators that define the myofascial and sensorimotor control DPs.8 Prolonged sensorimotor control dysfunctions may induce myofascial dysfunctions,44–46 but changes in myofascial structure and function may generate sensorimotor control problems.47 This may render it difficult to clearly distinguish between a dominant myofascial DP or sensorimotor control DP, as both ‘dysfunctions’ appear to merge.

Study limitationsThis study has several limitations. Firstly, the simultaneous examiner design may have caused bias toward overestimated interrater agreement values. Indeed, this design excludes the possible variability in assessments and patient–therapist interactions, that could occur in an independent-examiner design, which might result in lower levels of agreement.20

Secondly, the raters in this study had 6 years of experience with the classification under study. As such, the study results may not generalize to novice therapists or clinicians less familiar with mechanisms-based approaches.

Thirdly, the sample studied in the current study showed a preponderance of female patients (72.92%), and patients with headache (79.17%). A purposive, intentionally diverse sample might have been better to support the robustness of the reliability estimates. However, these patient characteristics appear to be typical for patients presenting with NSNP and correspond with the prevalence reported in the available literature.1,2,39,48–51

Finally, we did not test reliability of unique criteria. Consequently, we cannot comment on the capacity of a stand-alone criterion for a definitive decision regarding the classification. This is, however, beyond the scope of this study. In practice, most clinicians do not make clinical decisions based on a single test finding. Using clusters provide more promising findings and are more closely associated to clinical decision making.52

ConclusionsThe current study investigated the interrater reliability and agreement of a pain mechanism-based classification for patients with NSNP. Present findings suggest that physical therapists, acquainted with the classification strategy, are able to provide reliable ratings of individuals’ predominant pain mechanisms, pain patterns, and DPs underlying their NSNP. These results require careful interpretation. They are to be seen as clinically-oriented indirect classifications, based on a cluster of signs and symptoms, that presumably reflect the underlying pain generating mechanism, rather than a direct classification based on neurophysiology.20 The extent to which physical therapists can validly associate clinical patterns with the underlying pathophysiological mechanisms is still unclear.53 Future studies examining the clinical utility of mechanisms-based classifications of NSNP, by means of clinical trials with larger patient samples and various independent examiners, are the necessary next step to justify this approach for clinical use.

Conflicts of interestThe author declares no conflicts of interest