The Comprehensive Pain Management Editorial Series aim to contribute to the global implementation of pain science in clinical practice and facilitate clinicians providing individually-tailored multimodal lifestyle interventions for patients with chronic pain.1,2 Current treatment options, including pain science education and exercise therapy, for patients with persistent pain, often do not address the sleep disturbances so many patients with chronic pain experience. Therefore, this sixth paper in the Comprehensive Pain Management Editorial Series addresses this gap by discussing the importance of, and how clinicians can account for sleep disturbances as part of an individually-tailored multimodal lifestyle intervention for people with chronic pain. By doing so, sleep training contributes to a paradigm shift from a tissue- and disease-based approach towards individually-tailored multimodal lifestyle interventions for patients with chronic pain.1

Why sleep is important to consider in patients with chronic pain?Approximately one in every two patients with chronic pain have a severe sleep disturbance, most often insomnia.3-6 In cases when sleep disturbance is not better explained by other intrinsic sleep disorders (e.g., obstructive sleep apnea syndrome, restless legs syndrome) and inadequate opportunity or circumstances for sleep (e.g., shift work), insomnia in adults is defined as difficulties initiating and/or maintaining sleep for >3 days/week for >3 months with apparent daytime symptoms (e.g., fatigue, mood disturbances, cognitive impairment,…).7 Sleep disturbances have allegedly a bidirectional relation with chronic pain,4 act as a perpetuating factor for chronic pain,8 and if left untreated, represent a barrier for effective chronic pain management.9 Importantly, following a better night of sleep, patients with chronic pain spontaneously engage in more physical activity,10 underscoring the potential of interventions incorporating sleep training for patients with chronic pain and sleep disturbances. In addition, sleep is cardinal to the body's homeostasis, important for the regulation of a range of systems, such as the cardiovascular system, endocrine system, metabolism, body temperature, cell expression, and the immune system. Given its cardinal role in human health, the next section will focus on the role of sleep on the immune system.

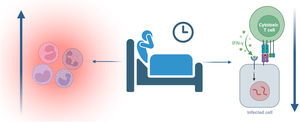

Sleep and the immune systemSleep has important restorative effects on the immune system: sleep results in a redistribution of immunocompetent cells from peripheral blood to secondary lymphoid organs where dendritic cells ‘train’ naive T-helper cells; sleep improves natural killer cell, monocyte, and lymphocyte activity; and shuts down the inflammatory system.11 Indeed, a good night of sleep has profound anti-inflammatory effects, while a lack of sleep or interrupted sleep triggers an inflammatory response (Fig. 1).12 The close link between sleep and inflammation should also motivate clinicians working with patients having inflammatory rheumatic diseases (e.g., osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis) to screen for sleep disturbances in this population.13 In addition, insomnia is associated with accelerated aging of the immune system (i.e., more senescent T-cells, decreased leukocyte telomere length, and epigenetic age acceleration in immune cells) and increased susceptibility to infections (Fig. 1).14 These are remarkable findings underscoring the key role of sleep in maintaining immune health in all patients with chronic pain, with particular relevance for patients with cancer and cancer survivors where insomnia and chronic pain are also highly prevalent.15

The interplay between sleep and stress in chronic painIn addition to sleep disturbances, stress (intolerance) also serves as an important perpetuating factor to many, if not all, patients with chronic pain, and has similar effects on immune health. Sleep and stress are closely related in patients with chronic pain,5 as supported by findings from numerous studies reporting strong associations between anxiety levels and insomnia severity.16,17 Worries about the next morning's workload can negatively impact sleep,18 while major stressful life events (e.g., wedding, divorce, becoming a parent) and/or traumatic events (e.g., natural disaster, combat, traffic accident) can result in alterations in the patient's sleep architecture, increased night-time arousal, and decreased sleep efficiency.18 The close stress-sleep interplay in patients with chronic pain is also illustrated by the findings from a successful trial of cognitive behavioural therapy for insomnia in patients with chronic pain, where responders not only showed a significant increase in perceived sleep efficiency but also a decrease in self-reported levels of distress.19 This comes as no surprise, given the inclusion of stress management as an integral part of cognitive behavioural therapy for insomnia (Table 1). The next episode of the Comprehensive Pain Management Editorial Series will tackle the emerging role of stress (intolerance) and its management in patients with chronic pain.

Main treatment components of cognitive behavioural therapy for insomnia.

| Component | Description |

|---|---|

| General sleep education | Explaining the importance of sleep and the behavioural neuroscience behind sleep, including the sleep regulatory principles, inter and intra-individual differences, and the predisposing, precipitating, and perpetuating factors of insomnia. |

| Sleep hygiene instructions | Promotion of sleep-stimulating behaviours (e.g., regular sleeping pattern) and reduction of sleep-interfering behaviours (e.g., late caffeine intake or smartphone use) via education and behavioural change counselling. |

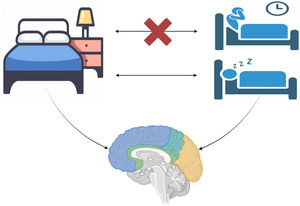

| Bedtime restriction therapy | Aims to increase homeostatic sleep drive by limiting time in bed to the average duration of sleep as recorded in a sleep diary, effectively re-establishing the association between being in bed and sleeping (Fig. 2). |

| Cognitive therapy (sleep-specific) | Focuses on identifying, challenging, and modifying negative or unhelpful beliefs and thoughts about sleep (e.g., misconceptions like sleep will only improve after pain resolution or beliefs of lifelong insomnia). |

| Stimulus control instruction | Using operant and classical conditioning principles to recreate the link between bed (-room) and sleep (Fig. 2). This may involve recommendations such as restricting bedroom activities to sleep and intimate activities, and leaving the bed and bedroom if unable to sleep. |

| Self-monitoring of daily sleeping pattern | Using a sleep-diary, asking patients to monitor their total sleep time, time in bed, sleep onset latency, and time awake after initial sleep onset. |

| Relaxation / Stress management | Teaches and practices stress management and relaxation techniques, such as mindfulness-based meditation, breathing exercises, or Jacobson's muscle relaxation. |

Many pain treatment programs today provide little other than the prescription of sedative pain/sleep medications to ‘manage’ insomnia (e.g., gabapentin, amitriptyline).5 However, pharmacological management of chronic insomnia should only be considered as second-line treatment (i.e., when cognitive-behavioural therapy for insomnia is not sufficiently effective), and only for short-term use and after careful consideration of the many potential negative side-effects and the addiction-risk.20 Indeed, cognitive behavioural therapy for insomnia is recommended as the first-line treatment for insomnia in adults of any age (including patients with comorbidities such as those having chronic pain or with a history of cancer (survivors), either applied in-person or a digital interface.21 Meta-analyses revealed that cognitive behavioural therapy for insomnia (which can be labeled in a non-stigmatizing manner to patients as ‘sleep training’) results in clinically significant immediate improvements in sleep quality, relatively small improvements in pain and fatigue, and moderate decreases of depressive symptoms in patients with cancer and non-cancer related chronic pain conditions, with improvements in sleep quality and fatigue maintained at 1-year follow-up.22-24 The main treatment components of cognitive behavioural therapy for insomnia are presented in Table 1, and include targeting the disrupted association between being in the bedroom and sleeping, with associated learning being used to restore this connection in the patient's insomniac brain (illustrated in Fig. 2).

Shortage of sleep therapists: opportunity for allied health professionals such as physical therapists?Despite its proven effectiveness, cognitive behavioural therapy for insomnia remains underused, especially in pain treatment programs, and is not readily available in clinical settings.25 Implementation barriers for cognitive behavioural therapy for insomnia include a shortage of trained therapists and lack of physicians trained in sleep problems which hamper its accurate diagnosis (including exclusion of sleep apnea).26,27 This creates opportunities for other (allied) healthcare practitioners such as occupational therapists, physical therapists, and nurses to fill this implementation gap. Indeed, exercise interventions may be useful as adjunct therapies to cognitive-behavioural therapy for insomnia,21 whether presented full-fledged or in its reduced form (Brief Behavioural Therapy for Insomnia28). Treatment protocols for integrating cognitive behavioural therapy for insomnia in current best-evidence treatment programs for patients with osteoarthritis and chronic neck and low back pain have been developed29,30 and are currently under examination in randomized clinical trials.