Physical therapists’ familiarity, perceptions, and beliefs about health services utilization and health seeking behaviour have not been previously assessed.

ObjectivesThe purposes of this study were to identify physical therapists’ characteristics related to familiarity of health services utilization and health seeking behaviour, and to assess what health seeking behaviour factors providers felt were related to health services utilization.

MethodsWe administered a survey based on the Andersen behavioural model of health services utilization to physical therapists using social media campaigns and email between March and June of 2017. In addition to descriptive statistics, we performed binomial logistic regression analysis. We asked respondents to rate familiarity with health services utilization and health seeking behaviour and collected additional characteristic variables.

ResultsPhysical therapists are more familiar with health services utilization than health seeking behaviour. Those who are familiar with either construct tend to be those who assess for health services utilization, use health services utilization for a prognosis, and believe that health seeking behaviour is measurable. Physical therapists rated need and enabling factors as having more influence on health services utilization than predisposing and health belief factors.

ConclusionPhysical therapists are generally familiar with health services utilization and health seeking behaviour; however, there appears to be a disconnect between what is familiar, what is perceived to be important, and what can be assessed for both health services utilization and health seeking behaviour.

Despite efforts to the contrary, healthcare costs in all nations continue to rise.1 In 2016, healthcare costs outpaced inflation rates by nearly twofold with the highest increases in Latin America, the Middle East and Africa, and Asia.1 In the United States, the growth rate of healthcare costs exceed that of annual income.2 Cost increases have been associated with several complex factors. One factor, known as “medicalization”, has received increased attention by public policy makers.3,4 Medicalization is the supposition that human conditions and problems can be defined and treated as medical conditions. This supposition has led to excessive use of diagnostic, preventative, and treatment options for a plethora of biological and behavioural disorders, many of which are not self-evidently medical.5 The process of providing potentially too much medical attention to those who do not need it is called over-medicalization.3

Only recently has the patient been identified as a potential collaborator in the complex problem of over-medicalization.6 Patients may demand services for unnecessary care, which leads to increases in health services utilization (HSU). HSU is defined as the quantity of health care services used (often measured by costs and visits).7 HSU rates are mediated by a number of factors, including patients’ health seeking behaviours (HSB). HSB is the individual's behaviour pattern that helps to explain HSU. Two ends of the spectrum exist for HSB: (1) those that need more care than they receive and (2) those that receive more care than they need. The former has been studied extensively focusing on those that need care, but do not receive it.8–11 This is especially true in countries where access to care is limited. The latter end of the HSB spectrum are those that frequent the health system despite a relatively lower actual need for the provided health service. HSB is a complex phenomenon that has been studied extensively by Andersen.12,13 HSBs are thought to be mediated by predisposing factors (e.g., age, sex, cultural, ethnic, and social factors), enabling factors (e.g., financial, organizational, and access to care), and need factors (e.g., one's views and experiences).

Healthcare providers that manage nonspecific conditions (e.g., low back and neck pain) with psychosocial influences are faced with higher risks of over-medicalizing patients because of uncertainty in diagnosis leading to extensive use of imaging and treatment strategies.14 In physical rehabilitation settings, the episode of total care or HSU (number of visits or length of service) is frequently determined by mutual provider/patient/payer decisions, and is rarely based on evidence or objective findings. Whereas HSU has been studied extensively in physical rehabilitation management of chronic musculoskeletal conditions,15–20 the behavioural component, i.e. HSB, has received much less attention, including assessment of healthcare provider familiarity, beliefs, and perceptions of the constructs. While the reasons for limited research on the emerging construct are unknown, it has been studied extensively in other conditions, especially mental health.13 We targeted physical therapists because they commonly care for patients as elective healthcare practitioners; and practitioners in elective settings more often deal with non-specific biomedical and behavioural musculoskeletal conditions, facing higher risks of over-medicalizing patients. Increasingly, physical therapists are responsible for managing patients through the evolving healthcare systems, which requires an understanding of the factors that influence HSU.21 We hypothesize that the majority of these providers are unfamiliar with both concepts. Therefore, the purposes of this study were threefold: (1) to survey autonomous physical rehabilitation providers’ familiarity and beliefs about HSU and HSB, (2) to identify provider characteristics related to familiarity of HSU and HSB, and (3) to assess what predisposing, enabling, and need factors these providers felt were related to HSU.

MethodsParticipantsThis study was a cross sectional survey design and was granted approval by the Rocky Mountain University (170311-05, Provo, UT, USA) and Duke University (Pro00081564, Durham, NC, USA) Institutional Review Boards. The survey was offered only in English. Participants were physical therapists recruited through social media and email between March through May of 2017. The use of social media for the recruitment of subjects has been shown to be an effective strategy.22–24 For social media, clinicians with large Twitter® or Facebook® connections were requested, twice, to post a link to the survey using a standardized statement about the study purpose. Physical therapists from all countries were eligible to respond. For the email solicitation, two listserv outlets were targeted: the Orthopaedic Section of the American Physical Therapy Association (APTA), and the American Academy of Manual Physical Therapy (AAOMPT). The listserv email was delivered one time each. Consent was embedded in the electronic survey.

Questionnaire development and structureQualtrics Software (Provo, UT) was used to develop the survey that was based on concepts used for surveying familiarity, beliefs, and perceptions.25 No previously validated surveys were available that measured familiarity, beliefs, and perceptions about HSU and HSB. Therefore, the survey used in this study was reviewed by practicing US Physical Therapists board certified in orthopaedics, along with researchers with expertise in survey development. The survey was piloted among clinicians of varying backgrounds to assess readability, clarity, and time to complete, and modified based on these assessments. Modifications made were primarily grammatical and user interface based.

The three purposes of the study were framed around the behavioural model proposed by Andersen and served as the foundational constructs for survey.13,26 Andersen has proposed that HSU is influenced by predisposing, enabling, and need factors as well as health beliefs.12 Predisposing factors include demographic and social factors. Political and cultural influences are accounted for in the predisposing category. The enabling category includes factors associated with access or barriers to care. Some examples of access to care factors are ability to pay for services and proximity to providers. Need factors are influenced by both the individual (perceived health status) and the provider (assessed health status). Finally, health beliefs include the attitudes, values, and knowledge an individual has about healthcare (e.g., exercise, nutrition, tobacco, and alcohol use).

Survey items were separated into four sections: (1) familiarity and utilization of HSU, (2) predisposing, need, and enabling factors, (3) familiarity and measurement of HSB, and (4) healthcare provider characteristics. The survey design included a maximum of 27 questions, in which respondents were guided to selected items based on the responses of filter questions. For example, when individuals indicated they were unfamiliar with HSU or HSB, additional detailed questions were skipped. In all cases, Qualtrics collected the IP address and controlled against multiple survey entries.

Provider demographic characteristicsThe demographics section consisted of eight questions, which included sex, age, and years and type of practice environment.

Familiarity with HSU and HSBFamiliarity with HSU and HSB were assessed using four-point Likert style questions ranging from none through high. For HSU, if the respondent was familiar with HSU, they were asked if they obtained HSU as part of the patient history, and if this information was used to make a prognostic decision.

Potential predictors of HSU and HSB familiarityThe following questions were asked to gain further insight into the factors that are associated with familiarity of HSU and HSB:

- -

Assess for HSU: Do you assess a patient's health-services utilization as part of your intake/history? (yes or no)

- -

HSU used for prognosis: Please rate your level of agreement with the following statement. History of health-services utilization is factored into the prognosis I provide my patient (strongly agree, somewhat agree, somewhat disagree, strongly disagree).

- -

Believe HSB is measurable: Please rate your perception that health-seeking behaviours are measurable for musculoskeletal disorders (not at all, slightly, moderately, highly measurable).

- -

Believe HSB influences outcomes: Please rate your level of agreement with the statement. Health-seeking behaviour has NO influence on outcomes for musculoskeletal disorders (strongly agree, somewhat agree, somewhat disagree, strongly disagree).

The respondent was asked to rate on a five-point Likert scale ranging from none-at-all to a-great-deal, how much they believed each possible need, enabling, and predisposing category influenced the prognosis of musculoskeletal disorders. Need factors (i.e., health status) included: (1) comorbidity, (2) disease severity, (3) disease duration, (4) depression, (5) medical complications, (6) pain intensity, (7) perceived health, (8) psychological distress, (9) quality of life, and (10) symptom severity. Enabling factors (i.e., access or barriers to care) included: (1) clinician characteristics, (2) geographic variables, (3) income, (4) insurance, (5) social support. Predisposing factors (i.e., demographic and social) included: (1) gender, (2) age, (3) marital status, (4) education, (5) socio-economic status, and (6) employment. In addition to these three primary categories, health beliefs were also addressed and included: (1) exercise and physical activity level, (2) tobacco use, (3) alcohol use, and (4) diet and nutrition. To make the results from these ratings clearer and to better encourage directionality, we dichotomized the findings, so that those factors rated as a lot or a-great-deal were collapsed together, and those that were rated as moderate or less were collapsed together.

Statistical analysisAll data was analyzed using IBM SPSS version 24.0 (IBM Corp, Armonk New York). Frequencies were evaluated to identify trends within each item. To gain further insight into the factors that are associated with familiarity of HSU and HSB, logistic regression was conducted and odds ratios (OR) were calculated using physical therapists’ characteristics variables as exposures (i.e., gender, age, years of practice, method of receiving survey). Statistical significance was set at p-value less than 0.05. We opted to dichotomize the independent predictors to better identify a direction within the decision-making structure. For each analysis, we dichotomized the Likert selections into high and low categories for each of the exposure variables, as follows:

- -

Assess for HSU: Responses were dichotomized so that those who rated this item as half of the time, most of the time, or always were in the high category, and those who rated it as sometimes or never were dichotomized into the low category.

- -

HSU used for prognosis: Responses were dichotomized so that those who rated it as strongly or somewhat agree were in the high category and those who rated it as somewhat or strongly disagree were in the low category.

- -

Believe HSB is measurable: Responses were dichotomized so that those who rated this item as moderate or highly measurable were in the high category and those that rated it as slightly or not at all measurable were in the low category.

- -

Believe HSB does not influence outcomes: Those that rated it as strongly disagree or somewhat disagree were dichotomized into the high category, and those that rated it as somewhat agree or strongly agree were categorized into the low category.

Familiarity with HSU and familiarity with HSB were used as both exposure and outcome variables. These were dichotomized so that those who rated their familiarity with each construct as moderate or higher were in the high category and those that rated it as less than moderate were in the low category.

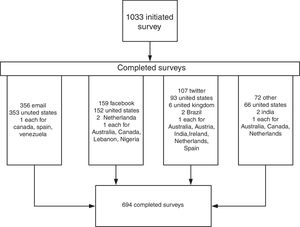

ResultsCharacteristics of participantsFig. 1 demonstrates the study flow. One-thousand and thirty physical therapists initiated the survey. Six-hundred and ninety-four physical therapists completed the survey in its entirety (338 female and 356 male). Physical Therapists from the United States made up 95.7% of the sample (n=664). Twelve other countries were represented in the survey (n=30), with the United Kingdom having the largest at seven.

Roughly half of the respondents (n=349) had 10 years or less of professional practice with 33.4% having five or less years (n=232). The majority of the respondents were under the age of 40 (58.6%, n=407) with 22.2% between the ages of 20 and 29 (n=154) and 36.5% between the ages of 30 and 39 (n=253). The percent of physical therapists that managed patients with a musculoskeletal condition was 89.3% (SD=13.6). The percent of time that the physical therapists were in clinical practice was 74.7% (SD=27.2). The method of receiving the survey was accounted for by email with 51.3% of the respondents (n=356). Social media accounted for 38.3% of the respondents (n=159 for Facebook, n=107 for Twitter), with the remaining coming from other sources.

Familiarity and beliefs about HSU and HSBThe majority of the respondents (60.5%, n=420) reported having at least moderate level of familiarity with HSU. However, a significant proportion had minimal (31.6%, n=219) or no (7.9%, n=55) familiarity with HSU. HSU information was obtained from patients as a part of the history most of the time or always in 45.4% of the respondents (n=290). The majority (86.1%) of the respondents agreed that HSU should be used for prognosis (strongly agree 34.3%, somewhat agree 51.8%).

Familiarity with HSB was rated slightly lower than HSU with 57.6% (n=400) of the respondents reported having at least moderate levels of familiarity. When asked about the influence that HSB has on musculoskeletal outcomes, the overwhelming majority (91.8%) rated it to have at least some level of influence. More than half of the respondents (51.7%) believed that HSB was measurable to some extent.

Physical therapist characteristics and familiarity with HSU and HSBBinomial logistic regression analysis identified male gender (OR 1.69, 95% CI 1.23, 2.27), HSU assessed in the history (OR 1.36, 95% CI 1.20, 1.54), HSU used for prognosis (OR 1.88, 95% CI 1.20, 2.96), familiarity with HSB (OR 3.81, 95% CI 2.99, 4.85), and belief that HSB has some level of measurability (OR 1.62, 95% CI 1.26, 2.08) as factors that predicted familiarity with HSU. A belief that HSB has some influence on outcomes (OR 1.40, 95% CI 0.79, 2.49) did not predict familiarity with HSU. These results are shown in Table 1.

Bivariate relationship for familiarity with HSU.

| Variable | Odds ratio (95% CI) | p value | Nagelkerke |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | 0.59 (0.44, 0.81) | <0.01 | 2.2% |

| Age | 0.99 (0.88, 1.14) | 0.98 | 0.0% |

| Years of practice | 1.02 (0.95, 1.10) | 0.59 | 0.0% |

| Method of receiving survey | 1.06 (0.92, 1.22) | 0.45 | 0.0% |

| Assess for HSU | 1.36 (1.20, 1.54) | <0.01 | 4.9% |

| HSU used for prognosis | 1.88 (1.20, 2.96) | <0.01 | 1.6% |

| Familiar with health seeking behaviour | 3.81 (2.99, 4.85) | <0.01 | 29.7% |

| Believe HSB influences outcomes | 1.40 (0.79, 2.49) | 0.25 | 0.3% |

| Believe HSB is measurable | 1.62 (1.26, 2.08) | <0.01 | 3.0% |

HSU, health services utilization; HSB, health seeking behaviour; CI, confidence interval.

Values in bold are statistically significant p<0.05.

Binomial logistic regression analysis identified male gender (OR 1.42, 95% CI 1.05, 1.92), HSU assessed in the history (OR 1.45, 95% CI 1.28, 1.64), HSU used for prognosis (OR 1.64, 95% CI 1.04, 2.57), familiar with HSU (OR 4.83, 95% CI 3.67, 6.36), and belief that HSB has some level of measurability (OR 1.78, 95% CI 1.39, 2.29) as factors that predicted familiarity with HSB. A belief that HSB has some influence on outcomes (OR 1.48, 95% CI 0.83, 2.61) did not predict familiarity with HSB. These results are shown in Table 2.

Bivariate relationship for familiarity with HSB.

| Variable | Odds ratio (95% CI) | p value | Nagelkerke |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | 0.70 (0.52, 0.95) | 0.02 | 1.0% |

| Age | 1.03 (0.91, 1.17) | 0.66 | 0.0% |

| Years of practice | 1.02 (0.95, 1.10) | 0.55 | 0.0% |

| Method of receiving survey | 1.11 (0.96, 1.28) | 0.14 | 0.0% |

| Assess for HSU | 1.45 (1.28, 1.64) | <0.01 | 7.2% |

| HSU used for prognosis | 1.64 (1.04, 2.57) | 0.03 | 1.0% |

| Familiar with health services utilization | 4.83 (3.67, 6.36) | <0.01 | 29.8% |

| Believe HSB influences outcomes | 1.50 (1.25, 1.80) | <0.01 | 4.3% |

| Believe HSB is measurable | 1.48 (0.83, 2.61) | 0.18 | 0.4% |

HSU, health services utilization; HSB, health seeking behaviour; CI, confidence interval.

Values in bold are statistically significant p<0.05.

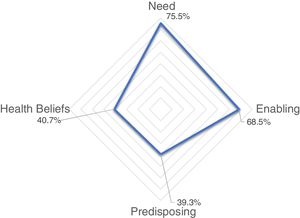

The results from the items that addressed need, enabling, predisposing, and health beliefs influences on prognosis are presented in Table 3. The factor that was most often believed to influence HSU was insurance (81.4%), an enabling category. The item that was least often believed to be a factor that influenced HSU was marital status (6.3%), a predisposing category. The overall category with the highest rating of influence on HSU was need, with a mean rating of 75.5%. This was followed by 68.5% for the enabling category, and 39.3% for the predisposing category. Mean rating for health beliefs was 40.7%. Fig. 2 demonstrates how much physical therapists believe each category influences HSU, with the lines in the radar plot represent percentage values in increments of ten.

Factors that physical therapists believed influence HSU.

| Factor that influences HSU | % of PTs rating it as a lot or great deal | % of PTs rating it as none, a little, or none |

|---|---|---|

| Need | ||

| Disease severity | 79.50 | 20.5 |

| Symptom severity | 78.80 | 21.2 |

| Psychological distress | 78.20 | 21.8 |

| Disease duration | 77.80 | 22.2 |

| Pain intensity | 77.00 | 23.0 |

| Depression | 76.60 | 23.4 |

| Medical complications | 74.70 | 25.3 |

| Quality of life | 72.30 | 27.7 |

| Comorbidity | 72.00 | 28.0 |

| Perceived health | 67.80 | 32.2 |

| Enabling | ||

| Insurance | 81.40 | 18.6 |

| Income | 69.60 | 30.4 |

| Geography | 65.10 | 34.9 |

| Clinician characteristics | 64.30 | 35.7 |

| Social support | 62.30 | 37.7 |

| Predisposing | ||

| Socio-economic status | 65.10 | 34.9 |

| Employment | 59.90 | 40.1 |

| Education | 52.90 | 47.1 |

| Age | 31.60 | 68.4 |

| Gender | 20.20 | 79.8 |

| Marital status | 6.30 | 93.7 |

| Health beliefs | ||

| Exercise/physical activity | 63.40 | 36.6 |

| Diet/nutrition | 38.50 | 61.5 |

| Tobacco use | 35.80 | 64.2 |

| Alcohol use | 25.20 | 74.8 |

HSU, health services utilization; PTs, physical therapists.

The purposes of this study were: (1) to survey physical therapists’ familiarity and beliefs about HSU and HSB, (2) to identify physical therapists’ characteristics that were related to familiarity of HSU and HSB, and (3) to rate the predisposing, enabling, need, and health status factors physical therapists felt were related to HSU. Several physical therapist's characteristics were significantly related to familiarity and knowledge of HSB and HSU and we feel this demands further discussion.

Familiarity with HSU and HSBThe results of this study suggest that the majority (60.5%) of physical therapists have at least moderate levels of familiarity with HSU. Likewise, the majority of physical therapists rated their familiarity with HSB as at least moderate (57.6%). Physical therapists were more likely to be familiar with HSU and HSB if they incorporated aspects of HSU into clinical decisions (i.e., assessed for it, used it for prognostic decisions, and believed that HSB was measurable). Most physical therapists reported that they used components of HSU, especially as a determinant for prognosis. Nevertheless, the majority (54.6%) reported that they do not obtain HSU information during the patient history. Over 90% of the respondents felt that HSB can influence musculoskeletal outcomes; however, roughly only half of the respondents felt that HSB was measurable. Moreover, the perception that HSB influences outcomes did not predict whether someone was familiar with the constructs of HSU or HSB. This result is consistent with a lack of research performed on HSB as a predictor of future outcomes, and suggests the need for further research to determine if HSB influences outcomes.

The predisposing, enabling, and need factors physical therapists felt were related to HSUChronic, and multiple chronic conditions are large determinants of future healthcare spending and utilization.27–32 However, to claim that HSU is only predicted by these factors would be short sighted, and thus a more complex approach to explaining utilization of healthcare is necessary. The behaviour model of HSU accomplishes this by incorporating need, enabling, and predisposing factors along with health beliefs. The items in this survey directly assessed the clinician's belief about each of these factors and its influence on prognosis. Need factors, such as condition severity, intensity, comorbidities, perceived health, and mental health status, were considered by physical therapists to have the most influence on a patient's prognosis. Fascinatingly, perceived health was rated to have the least influence on prognosis, though evidence suggests that perceived health does influence outcomes.33–38

The enabling category was not seen to be as influential on prognosis as the need category, with one exception, insurance. That insurance was frequently considered an indicator of prognosis, is somewhat expected, because most of the physical therapists surveyed in this study were from the United States, where insurance may be perceived as a barrier to care.

Physical therapists did not believe that the predisposing category influences prognosis as much as the need or enabling categories. As a matter of fact, gender, age, and marital status were among the factors rated as having the lowest influence on prognosis, even though research suggests these are physician and patient-expected predictors of outcomes.39 By nature of this being a self-report of clinicians, and not researchers, this finding might be partially explained by the experiences that physical therapists have in the clinic. It might also be explained by a potential lack of emphasis placed on these factors because they are deemed to be relatively non-modifiable. The only health status factor that physical therapists deemed important for prognosis was baseline exercise and physical activity levels.

Clinical implicationsPhysical therapists are responsible for managing the patient appropriately through the healthcare system. This includes recognizing patterns of healthcare utilization as part of the clinical reasoning. It is encouraging that physical therapists have some level of familiarity and utility with HSU and HSB. As a matter of fact, most of the factors in each of the categories of the HSB model were frequently considered to be important for influencing a prognosis. However, there is a gap between what is considered important to assess and what is actually assessed, possibly explained by a lack of literature on which HSB factors are important to address.

LimitationsIn an effort to include a highly variable sample of physical therapists, a social media campaign was developed with a focus on leveraging high impact social media resources including Twitter®, Facebook®, and LinkedIn®. One of the benefits of using social media for survey delivery is the ability to capture an international audience. Unfortunately, 92% of the respondents were from the United States. Furthermore, while the campaign was an initial success in achieving the sample size, it only accounted for half of the desired sample size. Therefore, email was needed to obtain the appropriate sample size. Because of how we obtained our sample, one of the greatest limitations in this study is that the findings are primarily from United States Physical Therapists, and that these results should only be interpreted in the context of the United States Health system.

Future directionsThe behavioural model of HSU has only recently been introduced in healthcare, with much of the literature pertaining to utilization of emergency room services.40–43 As demonstrated by the findings in this survey, there appears to be a recognition of the importance of HSU and HSB. However, what appears to be missing is an understanding of what factors are important to address with a patient, and how to assimilate this information. Future research should investigate the interaction of specific HSU and HSB factors and their relationship to outcomes of care, including future downstream consumption of health services.

ConclusionThe results of this cross-sectional study suggest that physical therapists have at least moderate levels of familiarity with HSU and HSB. Characteristics of clinicians who are familiar with these constructs tend to be those that integrate HSU and HSB as a part of clinical practice. Physical therapists rated need factors as prognostic determinants more than any other category; whereas, predisposing and health status factors were rated least often as prognostic determinants. These findings are important to consider because physical therapists are becoming more responsible for managing patients through the healthcare system.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.