Overall satisfaction with physical therapy care can improve patient adherence and active involvement in their management. However, which individual factors most influence satisfaction with private practice physical therapy care is not well established.

ObjectiveTo identify which aspects of the private practice musculoskeletal physical therapy experience best delineated “completely satisfied” and “dissatisfied patients”.

MethodsThe MedRisk Instrument for Measuring Patient Satisfaction with Physical Therapy Care (MRPS) was used in a cross-sectional design within 18 Australian private musculoskeletal physical therapy practices. The area under the curve (AUC) of receiver operator characteristic curves (ROC) was used to quantify the ability of the individual patient experience questions to classify the global impressions of satisfaction and likelihood to recommend to others.

Results1712 patients completed the survey (out of 7320 survey recipients - response rate 23%). High scores were identified for overall satisfaction (4.8/5 ± 0.61) and likelihood to recommend (4.78/5 ± 0.67). Individual items relating to education (AUC = 0.839 and 0.838) and shared decision making (AUC = 0.832 and 0.811) were the most accurate indicators of satisfaction and likelihood to recommend to others, respectively.

ConclusionIndividual questionnaire items relating to education and shared decision making were the most accurate indicators of satisfaction and likelihood to recommend in patients attending private practice musculoskeletal physical therapy in Australia. Clinicians and educators should focus on developing these skills to encourage an effective therapeutic alliance and promote greater levels of patient satisfaction.

Patient satisfaction is a critical consideration of patient-centred care1 in physical therapy as satisfied patients are more likely to be active participants in their care and adhere to treatment recommendations.2 Increasing patient involvement in their care is particularly important for individuals with musculoskeletal disorders as the burden of musculoskeletal disorders such as low back and neck pain is increasing, and is now the leading cause of years lived with disability in high income countries such as Australia, the United Kingdom, and France.3 Patients with musculoskeletal pain or disorders typically attend musculoskeletal physical therapy services delivered in private physical therapy clinics, or in emergency and outpatient departments within hospitals.4 In a fee for service setting, such as private musculoskeletal physical therapy clinics, ensuring patients are satisfied with the quality of their care has implications for business sustainability as satisfied patients are more likely to recommend the clinic or service to another individual.5 As has been shown in other industries,6 a high percentage of customers who actively “recommend” a product or service is strongly correlated with business growth which may be an important consideration for private physical therapy practice.

An important consideration with studies of patient satisfaction is determining how satisfaction is defined and measured - 'patient satisfaction with physical therapy experience/care' or 'patient satisfaction with treatment outcome'.7 Many of the parameters linked to 'patient satisfaction with physical therapy experience/care' can be directly modified, while ‘satisfaction with treatment outcome’ is typically related to resolution of pain or improvements in identified impairments8 which may be influenced by factors that are not easily modifiable such as (but not limited to) the type of condition/injury or the chronicity of the condition or responses to previous treatment.9 A recent systematic review identified that five out of six themes that contributed to patient satisfaction with musculoskeletal physical therapy related to the physical therapy experience/care rather than treatment outcome.10

While higher levels of patient satisfaction are associated with patients being more actively involved in their management, adhering to recommendations, and recommending the service to others, the individual factors that best delineate between satisfied and dissatisfied patients in private practice physical therapy are not clearly established. Most studies of patient satisfaction with musculoskeletal physical therapy have been conducted in outpatient settings9,11-13 or those that have been conducted in private practice settings were published at least 10 years ago with small (n<300) sample sizes.14,15 Consequently, key contributors to patient satisfaction in private practice (fee for service) settings requires further investigation. Understanding which factors most influence patient satisfaction in private practice can help clinicians and managers to identify which areas of the physical therapy experience should be prioritised or improved.

Therefore, the primary aim of this study was to identify which aspects of the private practice musculoskeletal physical therapy experience best delineated “completely satisfied” and “dissatisfied patients,” and those who were likely to or unlikely to recommend the service to others.

MethodsDesignA cross-sectional study of patients attending private physical therapy clinics in Australia for treatment of a musculoskeletal condition (e.g., back pain, knee pain, sporting injury).

Participants and clinicsParticipants were eligible for inclusion if they had attended at least two sessions for management of a musculoskeletal condition within a 12-month period (September 2020-September 2021), were aged over 18 years, and had sufficient English to read and understand the questionnaires. The minimum attendance at two or more therapy sessions was decided upon as it was thought that participants may not have been able to accurately answer each of the survey questions after attending a single session. Participants were recruited from 18 clinics in two states of Australia (Queensland and Victoria). Thirteen of the clinics were based in major cities and all clinics were part of one national allied health organisation.

Patient questionnairePatient satisfaction with physical therapy care was measured using the MedRisk Instrument for Measuring Patient Satisfaction with Physical Therapy Care (MRPS).12,16 The questionnaire contains 18 items about specific aspects of physical therapy care and two items about overall satisfaction. The MRPS is a reliable and valid tool to assess patient satisfaction in musculoskeletal settings.12,16,17 We used the original 20 item MRPS but modified question 20 from “I would return to this clinic for future services or care” to “How likely are you to recommend this service to a friend or family member?” as most individuals require a higher level of satisfaction and certainty in the quality of the health care services before recommending to others18 and this single question has been increasingly used to assess patient experience and health service evaluation across various health settings.19,20 In addition to the MRPS, four questions proposed by clinic directors were also included in the survey (Q21–24) to gain additional information about patient decision making (Q21) and patients’ perceptions of their physical therapist (Q22–24). Each item was scored on a five-point Likert scale of 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree) for all questions except question 20 which used different anchors on the five-point scale (1 = very unlikely, 5 = very likely). Further questions relating to sex, age, area of body treated, and the number of therapy sessions attended were included to identify whether patient satisfaction was influenced by such factors. A free-form question “Is there anything we can do to improve your experience at this clinic?” was included to provide respondents an opportunity for specific feedback.

ProcedurePatients presenting for physical therapy care were given the opportunity to complete the survey online via a specific link or a hard copy (informed consent was provided by participants electronically on the first page of the survey or via hand-written consent for those using hard copies). An email communication with a link to the survey was also sent out to patients who had opted into campaign marketing across the organisation and had attended at least two appointments in the previous 12 months. A follow up SMS reminder was sent out six weeks later. This project was approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee of the Australian Catholic University (2019–173E) and adhered to the STROBE statement.21

Statistical analysisFrequencies were calculated for the categorical variables (e.g., sex, age group, condition/area treated). Descriptive statistics were calculated for patient experiences items (MRPS Q1–18 and additional questions Q21–24), overall satisfaction (question 19), and likely to recommend (modified question 20). Although Likert scales are technically ordinal, they can be appropriately analysed using parametric statistics.22 Multivariate ANOVAs with the categorical variables as fixed factors were used to determine whether there were differences in the patient experience and global variables by sex, age group, or area/condition. Bivariate correlation coefficients between individual items (Q1–18 and Q21–24) and global ratings (Q19 and Q20) were identified. The following was applied to interpret the strength of correlations: 0–0.3 (negligible), 0.3–0.5 (low), 0.5–0.7 (moderate), 0.7–0.9 (high).23

The area under the curve (AUC) and their confidence intervals of receiver operator characteristic curves (ROC) were calculated to quantify the ability of the individual patient experience questions to classify patients as “completely satisfied” (Q19) or “likely to recommend” (Q20). While ROCs are traditionally used to assess diagnostic test accuracy, the AUC of ROCs and thresholds within ROCs have more recently been used to predict patient satisfaction following orthopaedic surgery24,25 and to establish cross-sectional relationships between different health outcomes.26,27 ROCs were used to identify which individual scores more accurately classified patients as “completely satisfied” or “not satisfied”, and “likely to recommend” or “unlikely to recommend.” A score of 5 (maximum score) on question 19 and 20 was used to indicate “completely satisfied” and “likely to recommend,” respectively. Consequently, scores of 4 and below were regarded as “not satisfied” and “unlikely to recommend,” respectively. The following thresholds were used to gauge ROC accuracy: ≥0.9 = excellent, ≥0.80 = good, ≥0.70 = fair, and <0.70 = poor.28

Free-form answers relating to things that could be improved were coded as: 0=nothing, 1=reception related, 2=price, 3=privacy, 4=clinic setting/organisation (eg. parking, waiting rooms), 5=clinician issues (eg. skill issues, communication).

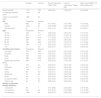

ResultsA total of 1712 responses were received out of 7320 survey recipients for a response rate of 23%. Most (86%) of the responses were completed online. 86% of respondents were classified as “completely satisfied” and 87% were “likely to recommend” (Table 1).

Summary of satisfaction, likely to recommend, and total MRPS scores amongst patient subgroups.

| Number | Percent | Overall satisfaction aMean (SD) | Likely to recommend a Mean (SD) | Mean score (MRPS 18-items) Mean (SD) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall sample | 1712 | 100 | 4.80 (0.61) | 4.78 (0.67) | 4.74 (0.40) |

| “Completely satisfied” (Q19) | 1479 | 86 | |||

| “Likely to recommend” (Q20) | 1488 | 87 | |||

| Sex | Frequency | Percent | |||

| Male | 588 | 35 | 4.77 (0.46) | 4.73 (0.64) | 4.73 (0.40) |

| Female | 1043 | 63 | 4.83 (0.56)b | 4.83 (0.59)b | 4.76 (0.37)b |

| Not disclosed | 81 | 2 | 4.00 (1.15) | 3.95 (1.36) | 4.21(0.67) |

| Age | Frequency | Percent | |||

| 18–24 | 128 | 7.5 | 4.89 (0.36) | 4.87 (0.51) | 4.77 (0.37) |

| 25–34 | 201 | 11.7 | 4.82 (0.60) | 4.79 (0.70) | 4.78 (0.36) |

| 35–44 | 255 | 14.9 | 4.77 (0.69) | 4.75 (0.77) | 4.74 (0.42) |

| 45–54 | 429 | 25.1 | 4.79 (0.59) | 4.80 (0.60) | 4.73 (0.37) |

| 55–64 | 449 | 26.2 | 4.75 (0.70) | 4.73 (0.75) | 4.71 (0.45) |

| 65–74 | 189 | 11.0 | 4.87 (0.45) | 4.87 (0.51) | 4.76 (0.36) |

| >75 | 11 | 0.6 | 4.82 (0.41) | 4.82 (0.41) | 4.84 (0.24) |

| Condition/area treated | Frequency | Percent | |||

| Low back | 557 | 32.5 | 4.82 (0.56) | 4.80 (0.63) | 4.76 (0.38) |

| Shoulder | 467 | 27.3 | 4.84 (0.51) | 4.83 (0.55) | 4.77 (0.35) |

| Neck | 399 | 23.3 | 4.80 (0.63) | 4.79 (0.68) | 4.75 (0.39) |

| Knee | 358 | 20.9 | 4.84 (0.51) | 4.80 (0.59) | 4.78 (0.35) |

| Middle back (thoracic spine) | 280 | 16.4 | 4.83 (0.56) | 4.79 (0.65) | 4.77 (0.37) |

| Hips | 274 | 16 | 4.83 (0.61) | 4.81 (0.63) | 4.76 (0.40) |

| Ankle/foot | 241 | 14.1 | 4.80 (0.61) | 4.82 (0.62) | 4.72 (0.39) |

| Other | 154 | 9 | 4.80 (0.61) | 4.78 (0.67) | 4.75 (0.38) |

| Elbow | 89 | 5.2 | 4.92 (0.31) | 4.89 (0.44) | 4.80 (0.30) |

| Wrist/hand | 79 | 4.6 | 4.89 (0.42) | 4.84 (0.63) | 4.79 (0.27) |

| Pelvis | 69 | 4 | 4.84 (0.50) | 4.86 (0.58) | 4.77 (0.32) |

| No specific region | 54 | 3.2 | 4.61 (0.94) | 4.59 (1.02) | 4.65 (0.50) |

| Head or jaw | 44 | 2.6 | 4.89 (0.44) | 4.89 (0.44) | 4.75 (0.32) |

| Number of physical therapy sessions | |||||

| <3 sessions | 90 | 5 | 4.61 (0.88) | 4.63 (0.85) | 4.57 (0.59) |

| 3–5 sessions | 607 | 36 | 4.72 (0.75) | 4.76 (0.63)c | 4.71 (0.39)c |

| >10 sessions | 1002 | 59 | 4.83 (0.57)c | 4.83 (0.56)c | 4.78 (0.39)c,d |

MRPS - MedRisk Instrument for Measuring Patient Satisfaction with Physical Therapy Care.

Table 1 shows that 63% of respondents identified as female and the most common decades for the age of participants were between 55 and 64 years and 45–54 years. Table 1 also shows the distribution of areas of symptoms and the number of sessions attended by respondents. Mean values for individual questionnaire items are presented in Table 2.

Overall satisfaction, likely to recommend, and total MRPS score were higher for females than males (p<0.001). There were no differences in the mean score of overall satisfaction, likely to recommend, or total MRPS score by age group. Higher scores were reported by respondents who attended a greater number of sessions for overall satisfaction, likely to recommend, and total MRPS score (p<0.05). Satisfaction or likely to recommend scores were not different for area/condition treated (Table 1).

All individual items were significantly correlated with each of the two global items (Table 2). Most correlations were low to moderate, with the highest correlation (0.59) identified for “My therapist listened to my concerns” and “My therapist answered all my questions.”

Individual item scores, and correlation with global satisfaction and likely to recommend scores.

| Questionnaire item | Mean (SD) | Correlation with Q19a | Correlation with Q20a |

|---|---|---|---|

| Q1 The office receptionist was courteous | 4.73 (0.61) | 0.45 | 0.44 |

| Q2 My therapist treated me respectfully | 4.91 (0.39) | 0.50 | 0.51 |

| Q3 The office staff were respectful | 4.79 (0.53) | 0.43 | 0.42 |

| Q4 My therapist listened to my concerns | 4.89 (0.44) | 0.59 | 0.57 |

| Q5 My therapist thoroughly explained my treatment | 4.85 (0.50) | 0.58 | 0.57 |

| Q6 My therapist answered all my questions | 4.87 (0.48) | 0.59 | 0.56 |

| Q7 The registration process was appropriate | 4.71 (0.64) | 0.46 | 0.47 |

| Q8 The therapist's assistant was respectful | 4.41 (0.91) | 0.35 | 0.34 |

| Q9 My therapist gave me detailed home program instructions | 4.75 (0.63) | 0.48 | 0.48 |

| Q10 The office hours were convenient for me | 4.80 (0.53) | 0.45 | 0.44 |

| Q11 My therapist advised me on how to avoid future problems | 4.61 (0.79) | 0.54 | 0.53 |

| Q12 The office and its facilities were clean | 4.87 (0.41) | 0.51 | 0.48 |

| Q13 My therapist spent enough time with me | 4.76 (0.67) | 0.58 | 0.54 |

| Q14 The office location was convenient | 4.78 (0.56) | 0.39 | 0.39 |

| Q15 I didn't wait too long to see my therapist | 4.78 (0.52) | 0.45 | 0.38 |

| Q16 The office used up-to-date equipment | 4.66 (0.69) | 0.48 | 0.43 |

| Q17 The waiting area was comfortable | 4.62 (0.68) | 0.44 | 0.40 |

| Q18 This office provided convenient parking | 4.54 (0.83) | 0.30 | 0.28 |

| Mean score (MRPS 18 items) | 4.74 (0.40) | 0.53 | 0.50 |

| Q19 Overall how satisfied were you with your experience | 4.80 (0.61) | 0.80 | |

| Q20 How likely are you to recommend service to friends or family | 4.78 (0.67) | 0.80 | |

| Q21 I feel I am involved in the decisions related to my care | 4.73 (0.62) | 0.58 | 0.53 |

| Q22 My therapist seems to have a genuine interest in me as a person | 4.80 (0.57) | 0.59 | 0.56 |

| Q23 My physical therapist considered my privacy and confidentiality | 4.81 (0.56) | 0.51 | 0.49 |

| Q24 My physical therapist seems to enjoy their work | 4.87 (0.44) | 0.57 | 0.61 |

The AUC for ROC analyses are shown in Tables 3 and 4. For satisfaction, all individual items except two (“My therapist treated me respectfully” and “This office provided convenient parking”) scored above 0.7, indicating at least “fair” classification ability. Three individual items scored above 0.8, indicating “good” classification ability. Only the total score of 18 items, scored above 0.9, indicating “excellent” classification ability. For likely to recommend, all individual items except two (“My therapist treated me respectfully” and “This office provided convenient parking”) scored above 0.7, indicating at least “fair” classification ability. Two individual items scored above 0.8, indicating “good” classification ability, and the total score of 18 items scored above 0.9, indicating “excellent” classification ability.

Area under the curve (AUC) of receiver operator characteristic curves for individual items relating to Q19 “Overall, I am completely satisfied with the services I received”.

| Questionnaire item | Area | Std. Errora |

|---|---|---|

| Q1 The office receptionist was courteous | .768 | .019 |

| Q2 My therapist treated me respectfully | .669 | .022 |

| Q3 The office staff were respectful | .724 | .021 |

| Q4 My therapist listened to my concerns | .723 | .022 |

| Q5 My therapist thoroughly explained my treatment | .753 | .021 |

| Q6 My therapist answered all my questions | .737 | .021 |

| Q7 The registration process was appropriate | .771 | .019 |

| Q8 The therapist's assistant was respectful | .740 | .018 |

| Q9 My therapist gave me detailed home program instructions | .761 | .020 |

| Q10 The office hours were convenient for me | .738 | .021 |

| Q11 My therapist advised me on how to avoid future problems | .839 | .016 |

| Q12 The office and its facilities were clean | .731 | .021 |

| Q13 My therapist spent enough time with me | .801 | .019 |

| Q14 The office location was convenient | .705 | .021 |

| Q15 I didn't wait too long to see my therapist | .746 | .020 |

| Q16 The office used up-to-date equipment | .796 | .018 |

| Q17 The waiting area was comfortable | .794 | .018 |

| Q18 This office provided convenient parking | .698 | .019 |

| Mean score (MRPS 18 items) | .930 | .010 |

| Q21 I feel I am involved in the decisions related to my care | .832 | .017 |

| Q22 My therapist seems to have a genuine interest in me as a person | .795 | .020 |

| Q23 My physical therapist considered my privacy and confidentiality | .754 | .021 |

| Q24 My physical therapist seems to enjoy their work | .741 | .021 |

Area under the curve (AUC) of receiver operator characteristic curves for individual items relating to Q20 “How likely are you to recommend this service to family or friends”?.

| Questionnaire item | Area | Std. Errora |

|---|---|---|

| Q1 The office receptionist was courteous | .768 | .020 |

| Q2 My therapist treated me respectfully | .679 | .023 |

| Q3 The office staff were respectful | .727 | .021 |

| Q4 My therapist listened to my concerns | .720 | .022 |

| Q5 My therapist thoroughly explained my treatment | .757 | .021 |

| Q6 My therapist answered all my questions | .729 | .022 |

| Q7 The registration process was appropriate | .783 | .019 |

| Q8 The therapist's assistant was respectful | .733 | .018 |

| Q9 My therapist gave me detailed home program instructions | .766 | .020 |

| Q10 The office hours were convenient for me | .734 | .021 |

| Q11 My therapist advised me on how to avoid future problems | .838 | .017 |

| Q12 The office and its facilities were clean | .723 | .022 |

| Q13 My therapist spent enough time with me | .784 | .020 |

| Q14 The office location was convenient | .713 | .021 |

| Q15 I didn't wait too long to see my therapist | .712 | .021 |

| Q16 The office used up-to-date equipment | .769 | .019 |

| Q17 The waiting area was comfortable | .771 | .019 |

| Q18 This office provided convenient parking | .691 | .020 |

| Mean score (MRPS 18 items) | .913 | .012 |

| Q21 I feel I am involved in the decisions related to my care | .811 | .019 |

| Q22 My therapist seems to have a genuine interest in me as a person | .783 | .020 |

| Q23 My physical therapist considered my privacy and confidentiality | .748 | .021 |

| Q24 My physical therapist seems to enjoy their work | .767 | .021 |

For the free-form question “Is there anything we can do to improve your experience at this clinic?”, most respondents (n = 1384) listed no/nothing. The most common feedback related to clinic setting/organisation (n = 128) such as parking and uncomfortable seating in reception areas, and therapist specific concerns (n = 105) such as poor communication, lack of skill or time spent with the therapist. Price (n = 49), privacy (n = 23) and reception staff concerns (n = 19) were less commonly reported.

DiscussionPatients attending Australian private practice physical therapy clinics were highly satisfied and were likely to recommend the service to their friends or family. The mean overall patient satisfaction score of 4.8 is higher than previously reported in private practice settings in Australia and the United States,14,29 and similar to findings from Brazil.17 These findings are based on more than 1700 responses, to our knowledge making our study the largest conducted exclusively within private musculoskeletal physical therapy settings. Satisfaction levels were higher for females than males which aligns with previous studies14 and may relate partly to males having higher expectations of care.9

The findings from this study indicate that together with the overall 18-item score, the individual items that most accurately classified patient satisfaction and likelihood to recommend were “My therapist advised me on how to avoid future problems” and “I feel I am involved in the decisions related to my care.” Our results align with previous findings from Australian and American outpatient settings that found items relating to patient-therapist interactions most strongly contributed to overall satisfaction,12,14 but these contributing factors appear to differ slightly between countries and settings. For example, while patient-therapist interactions and patient education were most strongly associated with overall satisfaction in Brazilian musculoskeletal settings17 and in Spanish-speaking American patients,30 extrinsic factors such as respectful office staff and office cleanliness were also strongly correlated with overall satisfaction. Extrinsic factors such as convenient location, parking availability, and courteous reception staff were only fair or poor predictors of patient satisfaction and likelihood to recommend in our study, further highlighting the importance of interpersonal attributes of therapists in contributing to patient satisfaction in an Australian private practice context.

In their systematic qualitative meta-summary, Rossettini et al.10 reported that therapist-patient relationship features such as tailored communication, and treatment features such as shared decision making and patient education, were some of the best strategies to increase patient satisfaction in musculoskeletal physical therapy. Our results affirm the findings from Rossettini et al.,10 and suggest that musculoskeletal physical therapists should focus on developing effective patient-centred communication and education skills to enhance the therapeutic alliance with their patients.31 A therapeutic alliance emphasizes building rapport to enhance patient motivation and a sense of ownership over the treatment plan.32 Of course, developing this therapeutic alliance requires adequate time spent with a patient and specific interpersonal communication skills such as empathy, confidence, and encouragement.10,33 As the item “My therapist spent enough time with me” was one of the items associated with satisfaction (AUC 0.801), ensuring that therapists spend enough time with patients to allow them to be listened to, promote shared decision making and, to provide education/advice33 is important for satisfaction. This is often perceived to be difficult in a fee-for-service setting where the number of patients seen is directly linked to revenue and is particularly challenging for inexperienced therapists,34 who are still in the early phases of developing their clinical reasoning, communication skills, and independence.35 Therefore, physical therapy programs, clinical placement opportunities, and senior clinicians should focus on developing students’/graduates’ ability to form strong therapeutic alliances and to facilitate shared decision making with their patients.36 To better understand how patients were involved in shared-decision making, future satisfaction studies should include a validated shared-decision making questionnaire such as collaboRATE.37

This study had some limitations including a low response rate (23%) which may have contributed to a positive response (1712 responses were received out of 7320 survey recipients). Most participants had attended at least 10 sessions of physical therapy and although other research has suggested patient satisfaction is high in Australian musculoskeletal physical therapy settings and compares favourably to international data,14 it is likely those patients who were dissatisfied would cease care and would be less likely to complete the survey. Therefore, the data from this study capture information on largely satisfied patients and does not encapsulate factors that led to dissatisfaction in musculoskeletal physical therapy. Additionally, we modified the wording of question 20 to better capture “promoters” without validating the modified question, which may impact the validity of the relationships identified for question 20. Another limitation of this study is that participants were all at different timepoints of care. Given the large sample size it would not have been pragmatic to administer region specific patient reported outcome measures, however a global rating of change scale could be included in future studies. Satisfaction of treatment outcomes was also not explored in this study, and while treatment outcomes are infrequently and inconsistently associated with patient satisfaction across musculoskeletal settings,17,29 identifying the association between 'patient satisfaction with physical therapy experience/care' and 'patient satisfaction with treatment outcome' may have provided additional insights. Finally, while the data were collected from 18 clinics, all the clinics were from one private musculoskeletal physical therapy group in Australia, predominantly in metropolitan areas. Therefore, these results may only be generalizable to Australian private practice musculoskeletal physical therapy settings.

ConclusionMost patients who completed the survey were highly satisfied with their physical therapy experience. The factors that most contributed to being satisfied and likely to recommend the service to others related to appropriate education/advice and shared decision making. Whilst often perceived to be difficult to implement in fee-for-service settings, the findings support previous studies that have highlighted the importance of adopting strategies that promote patient-centred care and therapeutic alliance. Clinicians and clinic owners can use these results to target professional development at improving these aspects of the physical therapy experience within the context of a private practice setting. Additionally, physical therapy educators should ensure that physical therapy programs and clinical placement opportunities adequately prepare graduates to facilitate shared decision making with their patients and deliver patient specific advice and education.

This study was supported by in kind administrative support from Healthia Ltd.

Vaughan Nicholson, Amy Papinniemi and Kerrie Evans are members of the Physiotherapy Clinical Advisory Board of Healthia Ltd.

Amy Papinniemi and Kerrie Evans are employees of Healthia Ltd.

The authors report no conflict of interest.

This study was approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee of Australian Catholic University (2019–173E).