Abdominal strength training before and during pregnancy has been recommended to enhance normal vaginal birth by enabling increased force needed for active pushing. However, to date there is little research addressing this hypothesis.

ObjectiveTo investigate whether nulliparous pregnant women reporting regular abdominal strength training prior to and at two time points during pregnancy have reduced risk of cesarean section, instrumental assisted vaginal delivery and third- and fourth-degree perineal tears.

MethodsAnalysis of 36124 nulliparous pregnant women participating in the Norwegian Mother and Child Cohort Study during the period 1999–2009 who responded to questions regards the main exposure; regular abdominal strength training. Data on delivery outcomes were retrieved from the Medical Birth Registry of Norway. Logistic regression analyses were used to evaluate the association between exposure and outcome before pregnancy and at gestational weeks 17 and 30.

ResultsAmongst participants, 66.9% reported doing abdominal strength training exercises before pregnancy, declining to 31.2% at gestational week 30. The adjusted odds ratios were 0.97 (95% CI 0.79–1.19) for acute cesarean section, among those training with the same frequency before and during pregnancy compared to those that never trained. The results were similar for instrumental assisted vaginal delivery and third- and fourth-degree perineal tear.

ConclusionThere was no association between the report of regular abdominal strength training before and during pregnancy and delivery outcomes in this prospective population-based cohort.

Today, healthy women are encouraged to engage in daily physical activity throughout pregnancy.1–3 Both endurance training and strength training are recommended, and from a health perspective pregnant women are encouraged to engage in 30min of moderate intensity aerobic training every day.1 Davies et al.2 recommend strength training of the major muscle groups 3–4 times per week and suggest that abdominal strength training is important to strengthen “the muscles of labor”.

Several studies have investigated the level of physical activity4–6 and exercise training7 during pregnancy in population-based studies. However, to date, there is scant knowledge to which extent pregnant women perform abdominal exercises. Strong abdominal muscles have been claimed to contribute to a more effective birth in terms of shorter duration of second stage of labor.8–10 Furthermore, Bovbjerg and Siega-Riz11 have postulated that strong abdominal muscles might make the second stage of birth more effective, thereby reducing the risk of failure to progress and cesarean section. The theory is that when the women are asked to actively push during the uterine contractions, strong and well-trained abdominals would improve the effectiveness of the pushing and thereby shorten the duration of the second stage of labor. Despite the Canadian recommendations2 and the aforementioned theories,8–11 there is a paucity of research addressing a possible association between strength training of the abdominal muscles and delivery mode.12 For this reason, the Norwegian Mother and Child Cohort Study (MoBa) included questions on abdominal training. MoBa is linked to the Medical Birth Registry of Norway (MBRN) and therefore allows analysis of exercise exposure and birth outcome.

The aims of the present study were to investigate:

- •

The number of women reporting to engage in strength training of the abdominal muscles before and during pregnancy.

- •

The association between self-reported abdominal strength training before and during pregnancy and acute cesarean section, instrumental assisted vaginal delivery and third- and fourth-degree perineal tear.

This cohort study is based on the data from the MoBa study conducted by the Norwegian Institute of Public Health.13,14

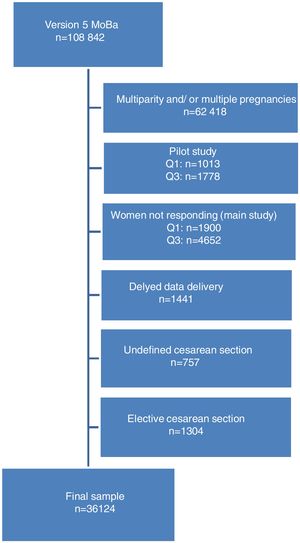

SettingParticipants were recruited from 52 hospitals in the period 1999–2008. The current prospective cohort study is based on version 5 of the quality-assured data file released for research in April/May 2011. Informed consent was obtained from each MoBa participant upon recruitment. The establishment and data collection in MoBa has obtained a license from the Regional Committee for Medical Research Ethics in South-Eastern (S-97045, S-95113) and the Norwegian Data Inspectorate (01/4325).

ParticipantsThe Moba cohort includes a total of 108000 pregnancies: 84200 children, about 90700 mothers and 71500 fathers. The women were recruited through postal invitation prior to the routine ultrasound examination in gestational weeks 17 and 18.13 The inclusion of study participants is shown in Fig. 1. Of the 108842 women included in the data file, approximately 60% were excluded because of multiparity and multiple pregnancies. An additional group was excluded because of participation in a pilot study where other questionnaires were used for our primary exposure variables (Questionnaires Q1 and/or Q3). Women not responding to Q1 and/or Q3 in the main study were also excluded. This left 39626 nulliparous pregnant women for inclusion in the present study. Due to delayed data delivery by MBRN, a group of women were excluded because of missing information on the study outcomes. We also excluded women with cesarean delivery other than acute (elective and undefined cesarean section). Thus the final sample comprises 36124 primiparous women with a singleton pregnancy.

MoBa questionnaires was sent out during and after pregnancy and included items about maternal, paternal, and the child's health and lifestyle. Three of the questionnaires were sent out during pregnancy. The questionnaires distributed at gestational weeks 17–18 and 30 included specific questions on abdominal, back, and pelvic floor muscle training and questions regarding habitual physical activity. The overall response rate for MoBa is 41%. Amongst women participating in MoBa, 94.9% completed the 17–18-week questionnaire and 91.8% the 30-week questionnaire.13

VariablesThe main exposure in the present study was maternal report of strength training of the abdominal muscles 3 months prior to pregnancy and at both time points during pregnancy. The women were asked to report frequency of abdominal strength training with the alternatives “never”, “one to three times per month”, “once a week”, “twice a week”, and “three or more times a week”. In the analyses, the categories “once a week” and “twice a week” were collapsed to one category “one to two times a week”, whereas the rest of the categories remained as original. The question was asked retrospectively at gestational week 17–18 (Q1) for the 3 months prior to pregnancy and cross-sectional for gestational week 17–18 (Q1) and week 30 (Q3).

The main outcomes were acute cesarean section, forceps, and/or vacuum-assisted delivery and third- and fourth-degree perineal tear as registered in MBRN.15 The outcomes were registered by qualified health personnel in a standardized form at the respective birth clinics. Forceps and vacuum-assisted deliveries were collapsed to one variable: instrumental assisted vaginal delivery. Third- and fourth-degree perineal tear were collapsed to one variable: third- and fourth-degree perineal tear.

Potential confounders for acute cesarean section, instrumental assisted vaginal delivery, and third- and fourth-degree perineal tear were selected based on literature review and cross-tabulations. The included confounders in the main analyses were: maternal age (continuous variable in years), pre-pregnancy body mass index (BMI) (kg/m2, continuous variable), highest level of education (categorized in primary school, secondary school, college/university), general physical activity level (defined as the frequency of participation in recreational activity, categories like the main exposure), pelvic floor muscle training (PFMT) (categorized like the main exposure), head circumference (cm), birth weight (defined as less than or more than 4000g), and dystocia (defined as yes or no registered by MBRN (analyzed for instrumental assisted vaginal delivery only)). Smoking and physically demanding work did not influence the estimates in subanalyses using logistic regression models and were consequently not included in the main analyses (in the subanalyses, we included the factors smoking and/or physically demanding work as additional factors to the main analyses to see the potential influence). We included the following covariates in additional subanalyses for each outcome to see whether they influenced the main analyses: (1) acute cesarean section: dystocia, fear of childbirth, induction of labor, and epidural; (2) instrumental assisted vaginal delivery: fear of childbirth, induction of labor, and epidural; and (3) third- and fourth-degree perineal tear: instrumental assisted vaginal delivery, fear of childbirth, and episiotomy.

Statistical methodsDemographical characteristics are presented as means with standard deviations (SD) or frequencies and percentages. Chi-square analysis was used to investigate the change in reported frequency of abdominal strength training during pregnancy. Separate logistic regression models were used to assess the association between the exposure and each of the three outcomes adjusting for potential confounders. Two models were constructed for each outcome. One model included reported abdominal strength training retrospectively for the period 3 months prior to pregnancy and the second model included reported abdominal strength training performed at all three time points (3 months prior to pregnancy, gestational weeks 17 and 30). In the analysis including all three time points, the exposure variable abdominal strength training had the following categories: training with the same frequency at all time points, training with a varied frequency at all time points seen together or no strength training of the abdominal muscles at all timepoints.16 The variable PFMT was categorized like the main exposure and the variable general physical activity level was taken from the time point 3 months prior to pregnancy. All the other variables in the analysis were similar in the two models. The reference group in both analyses was the group reporting no abdominal strength training. Only women with information on all included variables are included in the analyses. In the analysis of perineal tears, only women with vaginal deliveries were included. Thus, the sample sizes included in the different analyses differ between outcomes. The results are presented as crude and adjusted odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Statistical analyses were conducted with PASW Statistics for Windows, version 18 (Chicago, USA).

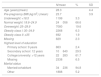

ResultsBackground variables are shown in Tables 1 and 2. The majority of the women had normal pre-pregnancy BMI, had completed higher education (college/university), and was married or cohabitants.

Demographic characteristics of the study participants (n=36124). Data presented as means with standard deviation (SD) or frequency (n) and percentages (%).

| N/mean | % | SD | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years)(mean) | 28.3 | 4.4 | |

| Pre-pregnancy BMI (kg/m2) (mean) | 23.7 | 3.9 | |

| Underweight: <18.5 | 1199 | 3.3 | |

| Normal weight: 18.6–24.9 | 24056 | 66.6 | |

| Overweight: 25–29.9 | 7080 | 19.6 | |

| Obesity class I: 30–34.9 | 2268 | 6.3 | |

| Obesity class II: ≥35 | 692 | 1.9 | |

| Missing | 829 | 2.3 | |

| Highest level of education | |||

| Primary school: 9 years | 863 | 2.4 | |

| Secondary school: 12 years | 10640 | 29.5 | |

| College/university: >12 years | 22283 | 61.7 | |

| Missing | 2338 | 6.5 | |

| Marital status | |||

| Married/cohabitant | 34236 | 94.8 | |

| Other | 1888 | 5.2 | |

BMI=body mass index.

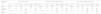

Participation in general physical activity of the study participants (n=36124). Data presented as frequency (n) and percentages (%).

| N | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Three months pre-pregnancy | ||

| Never | 2583 | 7.2 |

| 1–3 times per month | 4169 | 11.5 |

| 1 time per week | 4204 | 11.6 |

| 2 times per week | 4776 | 13.2 |

| ≥3 times per week | 20147 | 55.8 |

| Missing | 245 | 0.7 |

| Gestational week 17 | ||

| Never | 5926 | 16.4 |

| 1–3 times per month | 6238 | 17.3 |

| 1 times per week | 5650 | 15.6 |

| 2 times per week | 5037 | 13.9 |

| ≥3 times per week | 12383 | 34.3 |

| Missing | 890 | 2.5 |

| Gestational week 30 | ||

| Never | 9386 | 26.0 |

| 1–3 times per month | 6441 | 17.8 |

| 1 time per week | 5895 | 16.3 |

| 2 times per week | 4542 | 12.6 |

| ≥3 times per week | 9661 | 26.7 |

| Missing | 199 | 0.6 |

Amongst participants, 3999 (11.1%) underwent acute cesarean section, 6382 (17.7%) instrumental assisted vaginal delivery (forceps and vacuum), and 2051 (5.7%) had third- or fourth-degree perineal tear.

Numbers and percentages of women reporting to perform abdominal strength training before and during pregnancy are reported in Table 3. During pregnancy, there was a significant decline in number of women reporting abdominal strength training (p<0.001). Forty-seven percent of the women reduced their frequency of abdominal strength training from 3 months pre-pregnancy to gestational week 17. There was a further reduction in frequency of abdominal strength training from gestational week 17 to gestational week 30, 27% of the women reported to reduce their activity. At gestational week 30, 31% of the women reported to do abdominal strength training.

Frequency of abdominal strength training during three different time points: 3 months pre-pregnancy, gestational week 17 and 30 (n=36124). Data presented as numbers of women (n) and percentages (%).

| Time period | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency of training | 3 month pre-pregnancy | % | Gestational week 17 | % | Gestational week 30 | % |

| Never | 10964 | 30.4 | 19001 | 52.6 | 23425 | 64.8 |

| 1–3 times per month | 6853 | 19.0 | 6183 | 17.1 | 3887 | 10.8 |

| 1 time per week | 5401 | 15.0 | 4132 | 11.4 | 3538 | 9.8 |

| 2 times per week | 6724 | 18.6 | 2804 | 7.8 | 2320 | 6.4 |

| ≥3 times per week | 5218 | 14.4 | 1449 | 4.0 | 1556 | 4.3 |

| Total | 35160 | 97.3 | 33569 | 92.9 | 34726 | 96.1 |

| Missing | 964 | 2.7 | 2555 | 7.1 | 1398 | 3.9 |

Table 4 shows crude and adjusted odds ratios for report of abdominal strength training 3 months before pregnancy and acute cesarean section, instrumental assisted vaginal delivery, and third- and fourth-degree perineal tear. There was no significant association between abdominal strength training and any of the delivery outcomes. Adjusting for fear of childbirth, dystocia, induction of labor, epidural, episiotomy (for perineal tear only), or instrumental assisted vaginal delivery (for perineal tear only) had no influence on the results.

Logistic regressions for abdominal strength training 3 months pre-pregnancy and acute cesarean section (n=30178), instrumental assisted vaginal delivery (n=30178), and third- and fourth-degree perineal tear (n=26998) for the women in MoBa. Data presented as cOR and aOR with 95% CI.

| Frequency of training | Acute cesarean section | Instrumental assisted vaginal delivery | Third- and fourth-degree perineal tear | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | %so | cOR | 95% CI | aORcs | 95% CI | N | %so | cOR | 95% CI | aORid | 95% CI | N | %so | cOR | 95% CI | aORpt | 95% CI | |

| Never | 9622 | 11.3 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 9622 | 17.5 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 8535 | 7.0 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||

| 1–3 times a month | 5918 | 10.4 | 0.92 | 0.83–1.02 | 1.03 | 0.91–1.16 | 5918 | 17.0 | 0.97 | 0.89–1.05 | 0.98 | 0.89–1.09 | 5300 | 7.1 | 1.01 | 0.88–1.15 | 1.10 | 0.95–1.28 |

| 1–2 times a week | 10286 | 10.2 | 0.89 | 0.82–0.98 | 1.08 | 0.96–1.21 | 10286 | 18.3 | 1.05 | 0.98–1.13 | 1.06 | 0.97–1.17 | 9237 | 6.0 | 0.84 | 0.75–0.95 | 0.99 | 0.86–1.15 |

| ≥3 times a week | 4352 | 9.8 | 0.85 | 0.76–0.96 | 1.05 | 0.90–1.24 | 4352 | 16.9 | 0.96 | 0.87–1.05 | 1.00 | 0.87–1.14 | 3926 | 5.2 | 0.72 | 0.61–0.85 | 0.96 | 0.77–1.19 |

aOR, adjusted odds ratio; cOR, crude odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; N, frequency of participants.

Percentage of study outcome (acute cesarean section, instrumental assisted vaginal delivery, third- and fourth-degree perineal tear).

Adjusted for maternal age, pre-pregnancy body mass index (BMI), highest level of education, general physical activity level, PFMT, head circumference, and birth weight.

Table 5 shows the crude and adjusted odds ratios for report of abdominal strength training before pregnancy and at all time points during pregnancy combined and the delivery outcomes. There was no association between either varied training frequency or training with the same frequency before and during pregnancy with mode of delivery or perineal tears. Adjusting for plausible confounders (fear of childbirth, dystocia, induction or epidural, episiotomy (for perineal tear only), instrumental assisted vaginal delivery (for perineal tear only)) had no influence on the results.

Logistic regressions for abdominal strength training before and during pregnancy (3 months pre-pregnancy, gestational weeks 17 and 30) and acute cesarean section (n=29034), instrumental assisted vaginal delivery (n=29034), and third- and fourth-degree perineal tear (n=25992) for the women in MoBa. Data presented as cOR and aOR with 95% CI.

| Frequency of training | Acute cesarean section | Instrumental assisted vaginal delivery | Third- and fourth-degree perineal tear | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | %so | cOR | 95% CI | aORcs | 95% CI | N | %so | cOR | 95% CI | aORid | 95% CI | N | %so | cOR | 95% CI | aORpt | 95% CI | |

| Never | 6764 | 11.3 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 6764 | 17.4 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 6003 | 6.9 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||

| The same frequency | 2041 | 9.6 | 0.84 | 0.71–0.99 | 0.97 | 0.79–1.19 | 2041 | 17.5 | 1.00 | 0.88–1.14 | 0.99 | 0.83–1.17 | 1845 | 5.7 | 0.82 | 0.66–1.02 | 0.99 | 0.76–1.29 |

| Varied frequency | 20229 | 10.3 | 0.91 | 0.83–0.99 | 1.05 | 0.95–1.17 | 20229 | 17.6 | 1.01 | 0.94–1.08 | 1.04 | 0.96–1.14 | 18144 | 6.4 | 0.92 | 0.82–1.03 | 1.08 | 0.94–1.24 |

aOR, adjusted odds ratio; cOR, crude odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; N, frequency of participants.

Percentage of study outcome (acute cesarean section, instrumental assisted vaginal delivery, and third- and fourth-degree perineal tear).

Adjusted for maternal age, pre-pregnancy body mass index (BMI), highest level of education, general physical activity level (pre-pregnancy), PFMT (categories like the exposure), head circumference, and birth weight.

The main findings of this prospective pregnancy cohort study on abdominal strength training and delivery outcome were that two-thirds of the women reported to engage in strength training of the abdominal muscles before pregnancy. This declined to a third of the participants at gestational week 30. However, there was no association between maternal reports of abdominal strength training before and during pregnancy and acute cesarean section, instrumental assisted vaginal delivery, or third- and fourth-degree perineal tears.

The main strengths of the study are the large sample size and the access to longitudinal data on several exposures and plausible confounders. The MBRN is considered a reliable source of information related to birth,17 and in Norway this registration is mandatory for all women giving birth. The follow-up rate of more than 90% also strengthens the study.13 The study's hypotheses was not known to the women when they answered the questionnaires, which may limit the potential impact of information bias.

The main limitation of the study is the use of questionnaire data to assess frequency of abdominal strength training without any clinical assessment of actual abdominal muscle strength. Self-report may overestimate all training estimates and recall bias is a possible threat to the accuracy of self-report, in general. In the present study, retrospective maternal report of training 3 months before conception may be a special weakness.18 In addition, we have no information of the type of abdominal exercises (e.g. sit up or core stability training). Even with reliable self-reporting, there is no guarantee that the conducted abdominal strength training resulted in stronger abdominal muscles. Nevertheless, to date, there is scant knowledge about the effect of abdominal strength training in general during pregnancy, and as far as we have ascertained there are no studies evaluating the validity of report of abdominal strength training and actual increase in muscle strength. Combining the answers from three exposure points into one variable may improve the validity of the report as it indicates that the responders are “true” exercisers. Low response rate is one of the main challenges of conducting population-based studies. Nilsen et al.14 evaluated the differences between the participants in MoBa and the population in general to see whether there was a case of selection bias in MoBa. They found that younger and single women were underrepresented in MoBa, as also smokers. There were also a lower rate of preterm deliveries, lower gestational age, and babies with higher Apgar score and larger head circumference in the MoBa group. This can indicate a socioeconomic difference between MoBa participants and the population, in general.13 Such differences might affect the associations between the exposures during pregnancy and different outcomes.14 Thus, we cannot exclude that selection bias might have influenced our results. The gold standard design to rule out causality for abdominal strength training to influence delivery outcome would be a randomized controlled trial (RCT). However, given the low incidence of the main outcomes, a randomized controlled trial with these as main outcome variables would require a huge sample size and may not be feasible.

A few RCTs have reported the effect of strength training in relation to pregnancy and delivery.19–23 None of these studies found differences between the group that performed strength training and the group that did not train on delivery outcomes (acute cesarean section, instrumental assisted vaginal delivery). However, none of these RCTs had a primary aim to investigate the effect of abdominal strength training alone on acute cesarean section rate, instrumental assisted vaginal delivery, and third- and fourth-degree perineal tear. In addition, none measured abdominal strength before and after the intervention and none reported on which abdominal exercises that had been performed. Hence, to date, the evidence for the effect of abdominal strength training on delivery outcome is not clear.

To date, there is also scant knowledge about normal activity of the abdominal muscles during pregnancy and labor. Early studies from the 1950s and 1960s found that the electrical activity of the abdominal muscles decline as the pregnancy progresses.24,25 More recently, Oliveira et al.26 confirmed that there is activity in the abdominals during labor. They also found a negative correlation between the diastasis recti abdominis and electrical activity in m. rectus abdominis, but no correlation between the activity in m. rectus abdominis and m. obliquus externus and duration of second stage of labor. Buhimschi et al.27 investigated the change in intra-uterine pressure during contractions in the second stage of labor and found an increase of 62% when the mother performed the Valsava maneuver. To the best of our knowledge, there are no published studies on the effect of strength training on the abdominal muscles and the ability to increase intra-abdominal pressure in pregnant women. There is also uncertainty to the effect of different pushing techniques during delivery (open or closed glottal slit) and delivery mode.28,29 Women's health physical therapists are in close contact with pregnant women and are often asked questions about exercise during pregnancy. It is important that the advices and recommendations given by health personnel are evidence-based. Current recommendations for abdominal strength training during pregnancy are limited to advice against doing exercises in the supine position after the fourth month of pregnancy.30 To date, there is sparse knowledge on which abdominal exercises are safe for pregnant women both before and during pregnancy and especially the effect of abdominal training on birth outcome. The results of the present study indicate that abdominal training may not influence birth outcomes. However, there is an urgent need for further clinical studies to elaborate on this issue, both the role of the abdominal muscles during delivery and the effect of abdominal training during pregnancy on abdominal strength and how it may affect other outcomes. Hopefully our results will stimulate to more research.

ConclusionsA third of the participating women engaged in strength training of the abdominal muscles before and during all time points of their pregnancy. However, there was no association between self-reported abdominal strength training and delivery outcomes in this large population-based pregnancy cohort study. To be able to give pregnant women advice regarding abdominal strength training there is an urgent need for further research.

FundingThis research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sector. The Norwegian Mother and Child Cohort Study is however supported by the Norwegian Ministry of Health and Care Services and the Ministry of Education and Research, NIH/NINDS (grant no.1 UO1 NS 047537-01 and grant no. 2 UO1 NS 047537-06A1).

We are grateful to all the participating families in Norway who take part in this on-going cohort study. We also thank Professor Ingar Morten K. Holme for statistical advice, Maria Kristine Magnus for assistance with the MoBa data and Ingrid Nygaard for assistance with English revision.

This paper is part of a Special Issue on Women's Health Physical Therapy.