Recent evidence recommends Pilates for the treatment of chronic low back pain. However, it is still unknown if different weekly frequencies of Pilates can accelerate the improvement of symptoms in patients with chronic low back pain verified by a daily pain assessment.

ObjectiveTo analyze whether different weekly frequencies of Pilates can accelerate pain reduction by 30%, 50%, and 100% in patients with non-specific chronic low back pain and the necessary number of weeks to reach these improvements.

MethodsTwo hundred and twenty-two patients were randomized into three groups: Pilates group 1 received treatment once a week, Pilates group 2 received treatment twice a week, and Pilates group 3 received treatment three times a week. All groups received Pilates for six weeks. Pain intensity was measured daily before and after each intervention session using the Pain Numerical Rating Scale. The assessor was not blind.

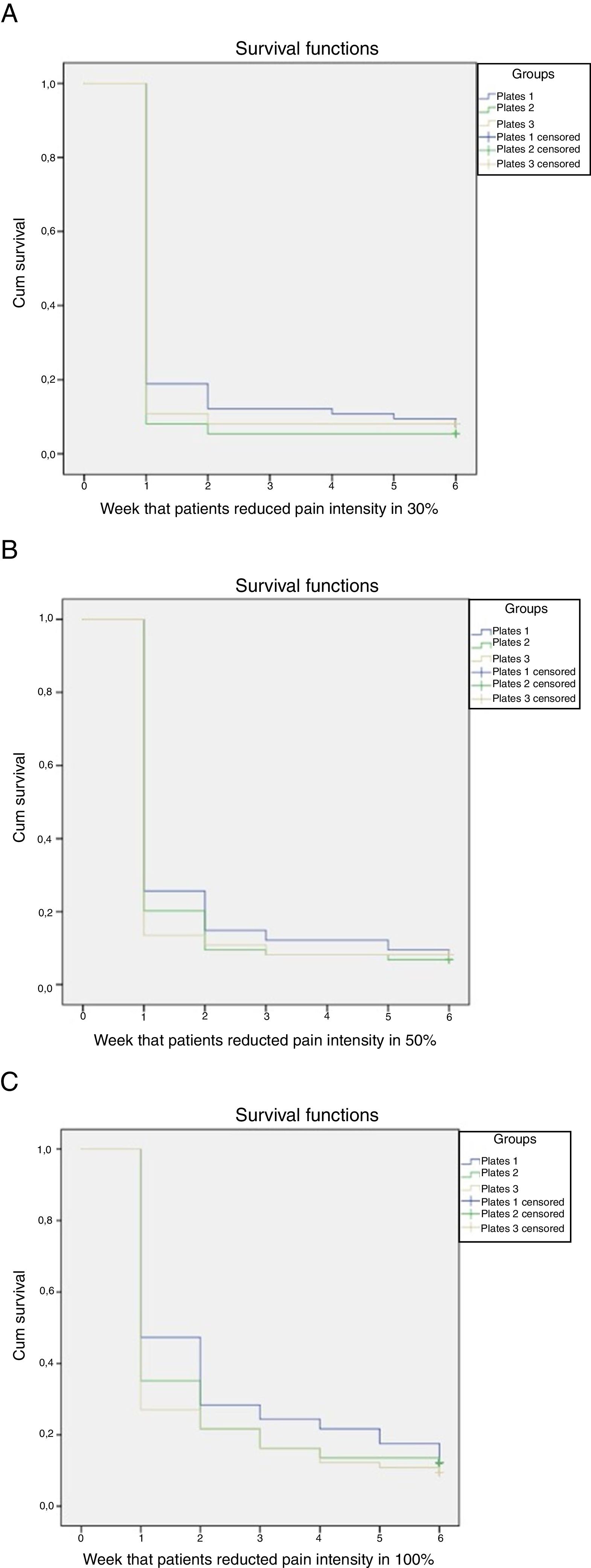

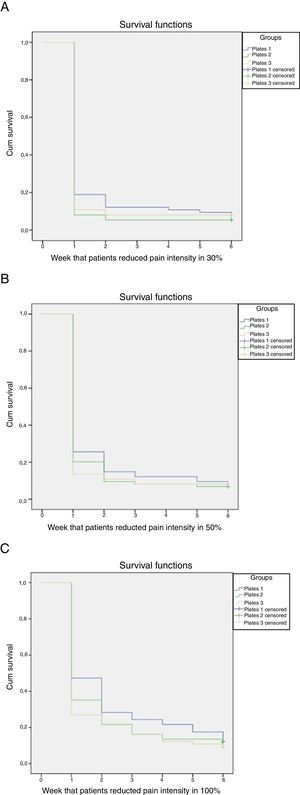

ResultsThe survival analysis showed that all Pilates groups had a pain reduction of 30%, 50%, and 100% at the same speed during treatment. There was no difference between the different weekly frequencies of Pilates for any of the comparisons (p>0.05). After the first week of treatment, 44.6% of the patients in Pilates group 3 showed complete pain improvement, followed by 37.8% of the patients in Pilates group 2 and 29.7% in Pilates group 1. After the last week, 71.6% (Pilates group 1), 77% (Pilates group 2), and 78.4% (Pilates group 3) of the patients reported complete improvement of symptoms.

ConclusionDifferent weekly frequencies of Pilates did not accelerate pain improvement in patients with non-specific chronic low back pain.

Registered in Clinical Trials Registry: NCT02241538 (https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02241538).

Non-specific chronic low back pain (CLBP) is characterized by pain or discomfort in the region between the costal margins and the inferior gluteal fold, with or without referred pain to the lower limbs, without serious spinal pathology or nerve root compromise, lasting more than 12 weeks.1,2 Low back pain is associated with high level of disability and absence from work.1 Estimates show the lifetime prevalence of low back pain to be 39%3 with the highest prevalence among women.4 Furthermore, low back pain is an important health problem with enormous socioeconomic costs. In the United States, $14.5 billion were spent with direct costs related to this condition.5

The non-pharmacologic treatments recommended by the clinical practice guidelines are manual therapy, supervised exercise, educational intervention, and cognitive behavioral therapy to improve symptoms of patients with non-specific CLBP.1,6–9 However, the effect size of these interventions is moderate.6,10 Furthermore, a specific intervention that promotes greater improvements in pain intensity compared to other intervention for these patients is still unknown.1,6,7 Although, the literature shows that exercise therapy may reduce pain by influencing the endogenous inhibitory system and inducing hypoalgesia.11–13

Only one study14 investigated the effects in terms of trajectories of pain, considering time-to-event outcome for patients with CLBP. This study14 evaluated daily pain intensity to identify whether active interferential current before Pilates exercises improved pain faster than placebo interferential current in patients with non-specific CLBP. The results showed that active interferential current presented a pain reduction of 30%, 50% and 100% faster than placebo interferential current.

Pilates is a specific type of exercise that promotes moderate improvements in pain and disability in the short-term and small improvements in the medium-term in patients with non-specific CLBP.15 Despite this evidence, it is still unknown whether different weekly frequencies of treatment (i.e., more or fewer sessions in the same week) based on exercise may accelerate pain reduction in these patients. Furthermore, there is no evidence about the effects in terms of trajectories of pain, considering time-to-event outcome for exercise therapy and different weekly frequencies in the treatment of patients with CLBP. Thus, the objective of this study was to analyze whether different weekly frequencies of Pilates exercises can accelerate pain reduction by 30%, 50%, and 100% in patients with non-specific CLBP and the necessary number of weeks to reach these improvements.

MethodsDesign overviewThis study is a secondary analysis of a published previously randomized controlled trial16 that evaluated the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of the addition of different doses of Pilates to a group receiving advice (a booklet with information on low back pain and anatomy of the pelvis and spine, and recommendations related to posture and movements of activities of daily living) for non-specific CLBP.16 In summary, two hundred and ninety-six patients were randomized to one of four groups (n=74 per group): booklet group with advice, Pilates group 1 (treatment once a week), Pilates group 2 (treatment twice a week), and Pilates group 3 (treatment three times a week). Randomization was generated in Microsoft Excel for Windows (Microsoft, Washington, USA) and treatment allocation was concealed through sealed opaque envelopes sequentially numbered by a blinded researcher. The assessor was blinded for patient allocation, however, due to the nature of the interventions, it was not possible to blind the patients and physical therapists responsible for the intervention. The main results of this randomized controlled trial showed that all Pilates groups were more effective than advice for patients with non-specific CLBP.16 Furthermore, Pilates twice a week was more effective than Pilates once a week,16 while Pilates three times a week was similar to Pilates once and twice a week.16 For cost-utility analysis, Pilates three times a week seemed to be the preferred option compared with other interventions.16 This study was previously approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Universidade Cidade de São Paulo (CAAE: 29303014.7.0000.0064), São Paulo, SP, Brazil. All patients signed an informed consent. This secondary analysis was planned prior to the beginning of the randomized controlled trial (prospectively registered in Clinical Trials Registry NCT02241538).

Setting and participantsThis study was conducted at a physical therapy clinic and a Pilates clinic in São Paulo, Brazil. In this secondary analysis, two hundred and twenty-two patients with non-specific CLBP with duration of at least three months and age between 18 and 80 were included. Only patients who did Pilates exercises were included. The exclusion criteria were serious spinal pathology or nerve root compromise, previous or scheduled spinal decompression surgery1, any contraindication to exercise,17 prior Pilates training in the last three months, and pregnancy.

InterventionsA detailed description of the Pilates exercise program has been given elsewhere.16,18,19 In brief, all patients in the Pilates groups received an individual exercise program including mat exercises (exercises performed on the ground with or without accessories) and apparatus Pilates exercises (exercises performed on the Barrel, Cadillac, Chair, and Reformer – Metalife, Santa Catarina, Brazil) for six weeks. In Pilates group 1, patients received six treatment sessions, in Pilates group 2, 12 treatment sessions, and in Pilates group 3, 18 treatment sessions. Sessions lasted one hour.

Physical therapistsFive physical therapists, certified in providing Pilates, with a mean of 7.5 years of experience in Pilates were responsible for the intervention. The physical therapists were certified in different Pilates schools. Thus, they received specific training on the Pilates-based exercise program for this study.

Outcome measurePain intensity was measured daily before and after each Pilates session using the 11-point Pain Numerical Rating Scale (0–10 points), with 0 being “no pain” and 10 being “pain as bad as could be”. Patients were asked to rate their average pain at the moment of the assessment.20 This assessment was conducted by the physical therapist responsible for the intervention, who was not blind to the intervention.

Statistical analysisA descriptive analysis of the mean values and standard deviation of daily pain intensity, before and after each Pilates session, was performed. A post-hoc survival analysis was performed to evaluate the number of weeks needed until pain was reduced by 30% (minimum clinically significant improvement), 50% (substantial improvement), and 100% (complete recovery) compared to initial pain reported at baseline.10,21 This analysis was performed using the Kaplan–Meier method,22 and the comparison between groups was performed using the log-rank test.23 For the survival analysis, we used the values of pain obtained before and after each session. Due to the heterogeneity of the number of sessions of the Pilates groups, we conducted the analyses per week of treatment since all groups received six weeks of treatment. In the data sheet, columns were created for a pain reduction of 30%, 50%, and 100%, and the week in which the patient reached these values was marked in the respective column. This week could be immediately before or after the Pilates session in any session received in the same week. In addition, columns were created with censored observations for the pain reductions of 30%, 50%, and 100% to mark whether the patients reached the desired values.

All data were entered twice into the data sheet. Data monitoring was performed by one researcher who was not involved with data collection and who was blind to group allocation. Data imputation was not performed. The analysis was performed according to the intention-to-treat principle. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS Version 24 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY, USA), and the level of significance was set at 5%.

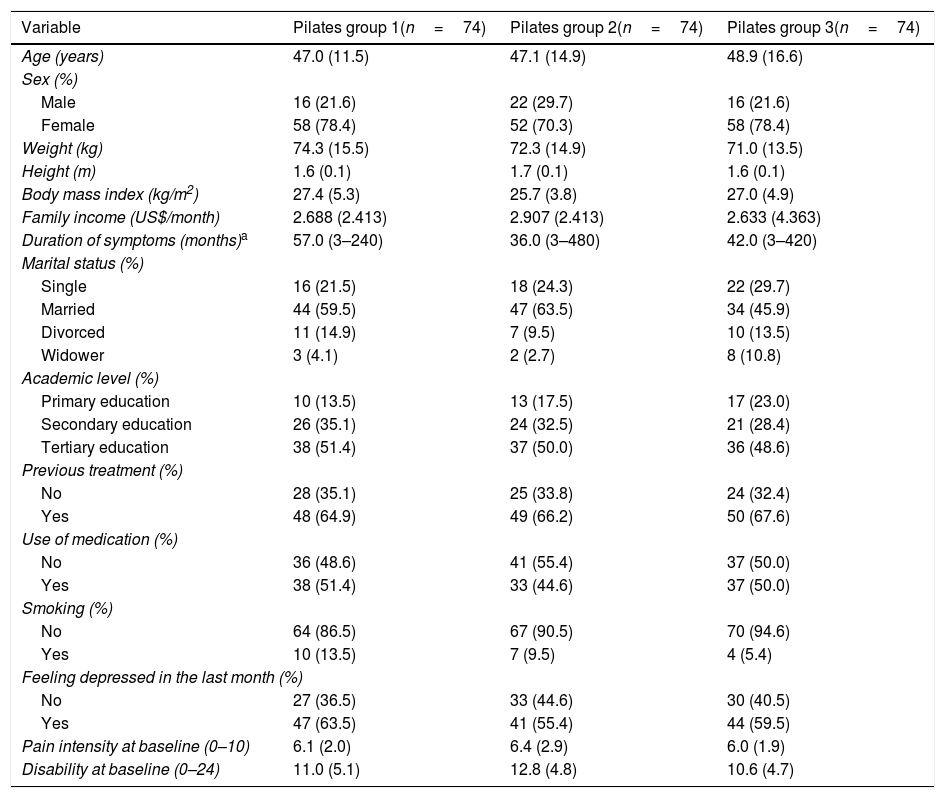

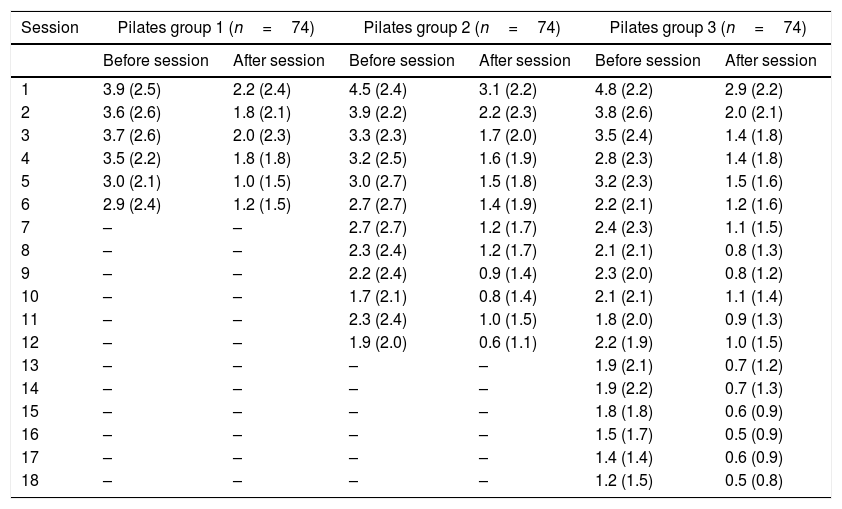

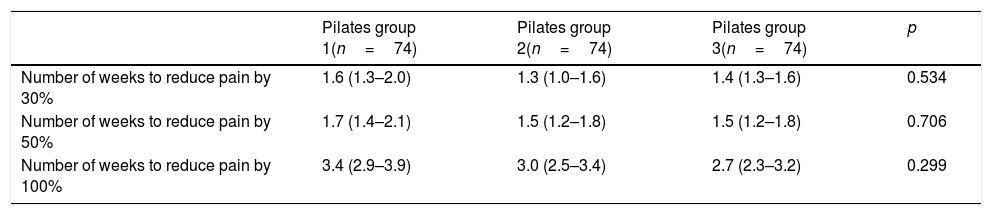

ResultsThe participants’ demographic characteristics are described in Table 1. Most patients were overweight, women, non-smoker, married, with tertiary education. The groups were similar at baseline. Most patients had received previous treatment for CLBP, felt depressed in the last month, and presented with moderate level of pain intensity and disability at baseline. Table 2 shows the mean and standard deviation of pain intensity before and after each session for all groups. It is possible to verify the reduction in pain intensity after each session in all Pilates groups. Patients presented a good adherence to the treatment, attending 85% of sessions for Pilates group 1 and Pilates group 2, and 82% of sessions for Pilates group 3. Table 3 shows the intergroup difference in the survival analysis. The results showed that all Pilates groups showed 30%, 50%, and 100% reduction in pain intensity at the same speed after treatment (Fig. 1). Furthermore, there was no difference between the different weekly frequencies of Pilates for any of the comparisons (p>0.05).

Patient characteristics.b

| Variable | Pilates group 1(n=74) | Pilates group 2(n=74) | Pilates group 3(n=74) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 47.0 (11.5) | 47.1 (14.9) | 48.9 (16.6) |

| Sex (%) | |||

| Male | 16 (21.6) | 22 (29.7) | 16 (21.6) |

| Female | 58 (78.4) | 52 (70.3) | 58 (78.4) |

| Weight (kg) | 74.3 (15.5) | 72.3 (14.9) | 71.0 (13.5) |

| Height (m) | 1.6 (0.1) | 1.7 (0.1) | 1.6 (0.1) |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 27.4 (5.3) | 25.7 (3.8) | 27.0 (4.9) |

| Family income (US$/month) | 2.688 (2.413) | 2.907 (2.413) | 2.633 (4.363) |

| Duration of symptoms (months)a | 57.0 (3–240) | 36.0 (3–480) | 42.0 (3–420) |

| Marital status (%) | |||

| Single | 16 (21.5) | 18 (24.3) | 22 (29.7) |

| Married | 44 (59.5) | 47 (63.5) | 34 (45.9) |

| Divorced | 11 (14.9) | 7 (9.5) | 10 (13.5) |

| Widower | 3 (4.1) | 2 (2.7) | 8 (10.8) |

| Academic level (%) | |||

| Primary education | 10 (13.5) | 13 (17.5) | 17 (23.0) |

| Secondary education | 26 (35.1) | 24 (32.5) | 21 (28.4) |

| Tertiary education | 38 (51.4) | 37 (50.0) | 36 (48.6) |

| Previous treatment (%) | |||

| No | 28 (35.1) | 25 (33.8) | 24 (32.4) |

| Yes | 48 (64.9) | 49 (66.2) | 50 (67.6) |

| Use of medication (%) | |||

| No | 36 (48.6) | 41 (55.4) | 37 (50.0) |

| Yes | 38 (51.4) | 33 (44.6) | 37 (50.0) |

| Smoking (%) | |||

| No | 64 (86.5) | 67 (90.5) | 70 (94.6) |

| Yes | 10 (13.5) | 7 (9.5) | 4 (5.4) |

| Feeling depressed in the last month (%) | |||

| No | 27 (36.5) | 33 (44.6) | 30 (40.5) |

| Yes | 47 (63.5) | 41 (55.4) | 44 (59.5) |

| Pain intensity at baseline (0–10) | 6.1 (2.0) | 6.4 (2.9) | 6.0 (1.9) |

| Disability at baseline (0–24) | 11.0 (5.1) | 12.8 (4.8) | 10.6 (4.7) |

Mean and standard deviation of pain intensity before and after each session for Pilates group 1, Pilates group 2, and Pilates group 3.

| Session | Pilates group 1 (n=74) | Pilates group 2 (n=74) | Pilates group 3 (n=74) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before session | After session | Before session | After session | Before session | After session | |

| 1 | 3.9 (2.5) | 2.2 (2.4) | 4.5 (2.4) | 3.1 (2.2) | 4.8 (2.2) | 2.9 (2.2) |

| 2 | 3.6 (2.6) | 1.8 (2.1) | 3.9 (2.2) | 2.2 (2.3) | 3.8 (2.6) | 2.0 (2.1) |

| 3 | 3.7 (2.6) | 2.0 (2.3) | 3.3 (2.3) | 1.7 (2.0) | 3.5 (2.4) | 1.4 (1.8) |

| 4 | 3.5 (2.2) | 1.8 (1.8) | 3.2 (2.5) | 1.6 (1.9) | 2.8 (2.3) | 1.4 (1.8) |

| 5 | 3.0 (2.1) | 1.0 (1.5) | 3.0 (2.7) | 1.5 (1.8) | 3.2 (2.3) | 1.5 (1.6) |

| 6 | 2.9 (2.4) | 1.2 (1.5) | 2.7 (2.7) | 1.4 (1.9) | 2.2 (2.1) | 1.2 (1.6) |

| 7 | – | – | 2.7 (2.7) | 1.2 (1.7) | 2.4 (2.3) | 1.1 (1.5) |

| 8 | – | – | 2.3 (2.4) | 1.2 (1.7) | 2.1 (2.1) | 0.8 (1.3) |

| 9 | – | – | 2.2 (2.4) | 0.9 (1.4) | 2.3 (2.0) | 0.8 (1.2) |

| 10 | – | – | 1.7 (2.1) | 0.8 (1.4) | 2.1 (2.1) | 1.1 (1.4) |

| 11 | – | – | 2.3 (2.4) | 1.0 (1.5) | 1.8 (2.0) | 0.9 (1.3) |

| 12 | – | – | 1.9 (2.0) | 0.6 (1.1) | 2.2 (1.9) | 1.0 (1.5) |

| 13 | – | – | – | – | 1.9 (2.1) | 0.7 (1.2) |

| 14 | – | – | – | – | 1.9 (2.2) | 0.7 (1.3) |

| 15 | – | – | – | – | 1.8 (1.8) | 0.6 (0.9) |

| 16 | – | – | – | – | 1.5 (1.7) | 0.5 (0.9) |

| 17 | – | – | – | – | 1.4 (1.4) | 0.6 (0.9) |

| 18 | – | – | – | – | 1.2 (1.5) | 0.5 (0.8) |

Estimates of mean and 95% confidence interval of the number of weeks required for a reduction of 30%, 50%, and 100% of the initial pain intensity.

| Pilates group 1(n=74) | Pilates group 2(n=74) | Pilates group 3(n=74) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of weeks to reduce pain by 30% | 1.6 (1.3–2.0) | 1.3 (1.0–1.6) | 1.4 (1.3–1.6) | 0.534 |

| Number of weeks to reduce pain by 50% | 1.7 (1.4–2.1) | 1.5 (1.2–1.8) | 1.5 (1.2–1.8) | 0.706 |

| Number of weeks to reduce pain by 100% | 3.4 (2.9–3.9) | 3.0 (2.5–3.4) | 2.7 (2.3–3.2) | 0.299 |

After the first week of treatment, 91.9% of the patients in Pilates group 2 showed a pain reduction by 30%, followed by 89.2% of the patients in Pilates group 3 and 81.1% of the patients in Pilates group 1 (Fig. 1A). Furthermore, 86.5% of the patients in Pilates group 3 showed pain reduction by 50%, followed by 79.7% of the patients in Pilates group 2 and 74.3% of the patients in Pilates group 1 (Fig. 1B). In addition, 44.6% of the patients in Pilates group 3 showed complete pain improvement (Fig. 1C), followed by 37.8% of the patients in Pilates group 2 and 29.7% in Pilates group 1.

After the last week of treatment, the results showed that 94.6% and 93.2% of the patients in Pilates group 2 improved pain by 30% and 50%, respectively. The results showed that 91.9% of the patients in Pilates group 1 and Pilates group 3 presented a pain reduction of 30% and 50%. Furthermore, 71.6%, 77%, and 78.4% of the patients obtained complete pain improvement in Pilates group 1, Pilates group 2, and Pilates group 3, respectively.

DiscussionThe aim of the present study was to analyze whether different weekly frequencies of Pilates exercises can accelerate pain reduction by 30%, 50%, and 100% in patients with non-specific CLBP and the number of weeks required to reach these improvements. The results showed that all weekly frequencies of Pilates exercises reached reduction in pain intensity of 30%, 50% and 100% at the same speed during treatment. Thus, there were no significant differences between Pilates groups. After the first week of treatment, most of the patients reduced pain intensity by 30% and 50% in all groups. Furthermore, most patients in all groups achieved completely recovery at the last week of treatment.

The strengths of this study are the randomization of patients and the concealed allocation. Furthermore, the study presented a large sample, demographic and clinical characteristics of the patients were homogeneous at baseline, and the analysis was performed according to principles of intention-to-treat. This is the first study that evaluated whether different weekly frequencies of a treatment based on exercise can accelerate the weekly improvement of pain intensity in patients with non-specific CLBP. In addition, this study is the first to quantify the reduction in pain intensity of 30%, 50%, and 100% in each week. This procedure allowed us to determine whether the different weekly frequencies of exercise therapy can accelerate the reduction in pain intensity after sessions of treatment. The limitation of this study was the heterogeneity of the number of sessions offered to patients in the groups (six, 12, and 18 sessions). Thus, it was not possible to perform a survival analysis per session of treatment. To solve this limitation, we decided to conduct the analyses per week of treatment. Another potential limitation was the inability to blind participants and physical therapists to treatment allocation due to the nature of the treatment.

At present, only two studies14,24 evaluated pain intensity before and after each session during the period of intervention of patients with CLBP. In one study,24 TENS, interferential current, and a control group were compared. The results showed no difference between the analgesic currents, but significant differences between both analgesic currents compared to a control group. However, this study24 did not present results about the trajectory of pain. Another study14 compared the effects of the active interferential current with the placebo interferential current before the Pilates exercises program in terms of trajectory of pain. The results showed that patients that received active interferential current reached pain reduction of 30%, 50%, and complete recovery (pain reduction of 100%) one, two and three sessions, respectively, before the placebo interferential current. In the present study, we did not find significant differences between different weekly frequencies of Pilates exercises. Furthermore, most of the patients showed a pain reduction of 30% and 50% after the first week of treatment, regardless of weekly frequency.

In this study, we did not compare the effect size or the number of patients that reached a pain reduction of 30%, 50%, and 100% between groups. We compared the number of weeks needed to reach a pain reduction of 30%, 50%, and 100% between groups. Thus, that comparison allows us to understand how the different weekly frequencies may influence the speed of improvement in pain intensity. Therefore, after the results of this study, we suggest that the decision of weekly frequencies of treatment based on Pilates exercises to accelerate improvement of pain in patients with CLBP be based on the provider's or patient's preferences. Future research can be conducted to evaluate the daily effects for pain intensity after treatment based on exercise therapy and the impact of this evaluation in patients with non-specific CLBP. These studies are needed to confirm the results of this study. Furthermore, new studies may help to estimate the number of sessions that are needed to reduce pain intensity by 30%, 50%, and 100% after treatment based on exercise, as well as the immediate effects of treatment.

ConclusionDifferent weekly frequencies of treatment based on Pilates did not accelerate the improvement of pain intensity in patients with non-specific CLBP.

Conflicts of interestThe second author (GCM) of this study declares conflict of interest because she was an instructor of NeoPilates courses. NeoPilates is a type of exercise that associates the principles of Pilates with the characteristics of functional training and circus. Although NeoPilates has similar name to Pilates method, the exercises are performed with different approach and in different equipment. Other authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Sao Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP process number 2013/26321-8) and National Council for Scientific and Technological Development(CNPq finance code 001).