This masterclass introduces the topic of core outcome sets, describing rationale and methods for developing them, and providing some examples that are relevant for clinical research and practice.

MethodA core outcome set is a minimum consensus-based set of outcomes that should be measured and reported in all clinical trials for a specific health condition and/or intervention. Issues surrounding outcome assessment, such as selective reporting and inconsistency across studies, can be addressed by the development of a core set. As suggested by key initiatives in this field (i.e. OMERACT and COMET), the development requires achieving consensus on: (1) core outcome domains and (2) core outcome measurement instruments. Different methods can be used to reach consensus, including: literature systematic reviews to inform the process, qualitative research with clinicians and patients, group discussions (e.g. nominal group technique), and structured surveys (e.g. Delphi technique). Various stakeholders should be involved in the process, with particular attention to patients.

Results and conclusionsSeveral COSs have been developed for musculoskeletal conditions including a longstanding one for low back pain, IMMPACT recommendations on outcomes for chronic pain, and OMERACT COSs for hip, knee and hand osteoarthritis. There is a lack of COSs for neurological, geriatric, cardio-respiratory and pediatric conditions, therefore, future research could determine the value of developing COSs for these conditions.

The efficacy or effectiveness of health interventions is ordinarily assessed in randomized clinical trials which compare the outcome of the health intervention under study with a control group such as placebo treatment (for efficacy trials), or alternatives such as usual care or no treatment (for effectiveness trials).1 Since outcomes are supposed to reflect beneficial and adverse effects of the interventions, they need to be appropriate and assessed with validated instruments to make the comparison meaningful (i.e., clinical trials are only as credible as the precision of their methodology, including the appropriateness and quality of their endpoints).2 Notwithstanding these considerations, there are numerous issues surrounding experimental design, data analyses, and interpretation of results as well as the adequacy of outcomes assessment in clinical trials. There has been a long history of publications regarding the methodology of clinical trials and data analytic strategies and interpretation. Recently greater attention has been given to the composition of the end-points that should be considered as outcomes in clinical trials, ensuring that they are of importance to patients, and encouraging use of the same measures across studies.

Currently, outcomes are often not measured and reported consistently across clinical trials for the same health condition and/or intervention.3 This hampers the ability to compare and pool results from different trials, and reduces the statistical power and precision of meta-analyses.4 As an example, a systematic review including 171 clinical trials investigating physical therapy interventions for shoulder pain found that overall there was a large diversity of outcomes assessed across trials, and that only three were assessed by a large majority of trials.5 An additional problem is selective outcome reporting bias where authors report only outcomes for which there are favorable results.6 This may bias the interpretation of the results of clinical trials and systematic reviews.7 For instance, two large Cochrane reviews on the effectiveness of rehabilitation interventions for low back pain (LBP) found that the large majority of trials presented an unclear or high risk of outcome selective reporting.8,9 Outcomes of trials also need to be relevant to patients, whose views should be incorporated when considering outcome choices.10,11

The development of a core outcome set (COS) has been suggested as a way of addressing these issues and aim to reduce outcome irrelevance, inconsistency and selective reporting.12

What is a core outcome set?A COS is an agreed, standardized and minimum set of outcomes that should be measured and reported in all clinical trials for a specific health condition.13 This core set should be consensually agreed to by all the relevant stakeholders (e.g., health care professionals, researchers, policy makers, people who fund health services and research, industry representatives, patients, and the public).14 A COS does not mandate which outcome(s) should be designated as primary outcome(s) in a trial, and does not preclude measurement of additional outcomes if relevant to a specific trial. Decisions about primary and secondary outcomes should be specific to the research question of interest and possibly the treatment being evaluated. For example, the most relevant primary outcome for a trial evaluating an analgesic would be a measure of pain, whereas for a rehabilitation trial it might be physical functioning. In general, the primary outcome of a trial will often coincide with one of the COS outcomes as these putatively represent the most relevant outcomes.13

Evidence-based synthesis and meta-analyses could be substantially improved if there was greater outcomes consistency, as more trial results could be included in pooled analyses and this would result in more precise estimates of the effectiveness of interventions.4 The uptake of COSs in systematic reviews is gradually increasing,15 and a survey of Cochrane editors showed strong support for use of COSs in Cochrane reviews and agreement that reliability of the reviews could benefit.16 One way to implement COSs in Cochrane reviews is to include their outcomes in Summary of Findings tables which were developed by the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) initiative to provide a summary of the overall quality of the evidence, an estimate of the treatment effects and the uncertainty around those estimates.17 These tables were developed to provide an abbreviated overview of the reviews’ results for clinicians, consumers and others.18

Visionary work in this research field has been conducted by the Outcome Measures in Rheumatology (OMERACT) initiative which has been developing COS for rheumatologic conditions for 25 years.2,14 In more recent times, the Core Outcome Measures in Effectiveness Trials (COMET) initiative was created, with the goals of raising awareness around COSs and of supporting methodological research around this topic.19 OMERACT and the COMET initiatives both agree that the development of a COS requires consensus to be reached through a stepwise approach, firstly on ‘what’ to measure (i.e. the core outcome domains that should be measured), and, secondly on ‘how’ to measure (i.e. the core outcome measurement instruments that should be used to measure the core domains).13,20

How to develop a core outcome set?The first step in the development of a COS is to establish its scope, i.e. to determine which population, interventions, study design and/or settings, the COS should apply to.13,20 Regarding the scope, there are COSs that have been developed to apply to the effectiveness of all interventions for a quite generic health condition, such as the Initiative on Methods, Measurement, and Pain Assessment in Clinical Trials (IMMPACT) which focuses on all interventions for all chronic pain conditions.21 Other COSs have been developed for one specific intervention, e.g. the VAPAIN initiative that focuses on the effectiveness of only multidisciplinary interventions for chronic pain conditions.22 Researchers who intend to develop a new COS should determine whether similar initiatives already exist and how much overlap there might be.13 Ideally, the development of a COS should include appropriate stakeholders including relevant patient target groups.13 The involvement of patients has been suggested by the OMERACT initiative as essential for every COS effort,11,14 because studies involving patients frequently identify key outcomes that had not been otherwise considered.23–25

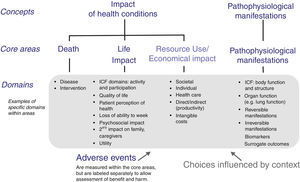

Reaching consensus on the core outcome domains can be a multi-stage process. Various COS protocols for this step have been published, but they all adopt methodologies that vary at least in part.22,26–30 As the first step in development of a COS, a list of potential core outcome domains (health constructs to be measured) is identified from literature review, clinicians and researchers who treat patients with the condition and intervention under study, and patient experience. The OMERACT framework was developed to ensure content validity of every COS and it encompasses important health aspects that should be considered (Fig. 1).20 It includes four core areas, three of which are recommended to be included in every COS (‘death’, ‘life impact’, and ‘pathophysiological manifestations’), and one strongly suggested to be included (‘resource use’).20 In this framework, the domain of ‘Death’ might refer to death causes and time-frame of mortality, or to numbers of deaths in trials in which mortality is very rare.20 ‘Life impact’ includes symptom and functional status domains, and could correspond to the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) areas of activity limitations and participation restrictions.20 ‘Pathophysiological manifestations’ could correspond to the ICF body function and structure core area, and could include biological and physiological variables that can be measured; ‘Resource use’ refers mainly to societal costs.20

OMERACT conceptual framework of core areas for outcome measurement in the setting of clinical trials. The choice of specific domains within a core area depends on the context for which the core outcome set is developed, e.g. domains can be generic- or disease-specific, or time-specific.

Outcome domain labels and definitions could be taken from other existing health frameworks (e.g. the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF),31 the Wilson–Cleary model of health-related quality of life,32 or the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) health framework).33 A systematic literature review can be conducted to identify all the domains routinely reported in clinical trials to draft an initial list of potential core outcome domains, and there are examples for rehabilitation interventions of such reviews.5,34 At the same time, focus groups or cognitive interviews with clinicians and patients can be conducted to ensure that the most relevant domains from their perspective are included in the list. A good example of qualitative research with patients is provided by Hush et al. who attempted to determine which domains characterize ‘recovery’ in patients with LBP.35

Following the development of a list of potential core outcome domains, agreement on a set of core outcome domains should be achieved among various stakeholders. Different methods for reaching consensus exist including unstructured group discussions (e.g., task forces, work groups, expert panels), semi-structured group discussions (e.g., nominal group technique), or structured surveys (e.g., Delphi technique).36 A recent systematic review found that the Delphi survey is the most frequently used method in COS development, often preceded by a literature review or combined with a nominal group technique.36,37 The Delphi technique consists of sequential questionnaires that constitute consecutive rounds in which anonymous respondents take part; after each round, the group responses are fed back to the respondents who can reconsider their views based on the report of the group views.38 Recent methodological work highlighted that receiving feedback from different groups of stakeholders is essential as it influences the level of consensus and the final COS.39 Overall, there is no agreed standard methodology for the development of a core set (e.g. as there is for clinical trials or systematic reviews) and it is unknown whether an optimal methodology exists. Nevertheless, a clear and transparent reporting of a COS development study is fundamental and the Core Outcome Set-Standards for Reporting (COS-STAR) statement has recently been published to facilitate reporting of these studies.40

After reaching consensus on a core set of outcome domains the next step in COS development is to identify and select instruments that represent and assess those domains.13,20 In 1998, the OMERACT filter was proposed as a procedure to use for the selection of instruments.41 It summarizes the measurement properties that are needed in a measurement tool in terms of their “truth, discrimination, and feasibility”. “Truth” refers to the ability of an instrument to measure what is intended to measure, and it captures aspects of face, content, and construct validity (and criterion validity, when applicable)42; “discrimination” refers to aspects of reliability and responsiveness, and therefore to the capability of an instrument to discriminate individuals and groups at one or different time points43; “feasibility” considers if an instrument is easily applicable in a given setting, taking into account mode of administration, time, costs, interpretability, respondent burden, and other aspects.43 According to OMERACT, an instrument should only be considered to measure a domain in a COS if it meets all three requirements of the filter. More detailed instructions on how to apply this filter is presented in the OMERACT handbook.44

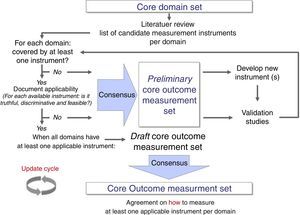

Some literature on how to select core outcome measurement instruments has been lately published.45,46 Recently, OMERACT, COMET, and the Consensus-based Standards for the selection of health Measurement Instruments (COSMIN)47 worked together to produce structured guidance on the selection of measurement instruments.46 This guidance emphasizes that, after having defined all, or as a minimum, the most promising potential core outcome measurement instruments, researchers should perform a thorough review of their measurement properties (i.e., validity, reliability, and responsiveness) and feasibility.46 Methodologically sound systematic reviews are the best procedures to synthesize evidence on measurement properties of an instrument.47 There are various examples of well-performed reviews, and these can focus on one specific instrument only,48,49 on the direct head-to-head comparison of multiple instruments,50 on a range of instruments measuring the same health construct,51 or on all generic- or disease-specific instruments for a given health condition.52,53 It has been suggested that only one instrument per core outcome domain should be selected, and that an instrument should have at least high quality evidence for good content validity and good internal consistency (when applicable), and be feasible to be included in a COS.46 Finally, a consensus procedure should be adopted for having different stakeholders reach agreement on which core outcome measurement instruments to include in a COS (Fig. 2).20,46

Development process of a core outcome set from a set of core outcome domains to reach consensus on core outcome measurement instruments (i.e. core outcome measurement set). As depicted, this process allows core set developers to establish a preliminary core outcome measurement set when not all domains are covered by at least one applicable measurement instrument.

Another crucial aspect in the development of a COS is to reach consensus on the interpretation of scores of the core outcome measurement instruments. Although methodology for how to reach this consensus is scant, examples, published by the IMMPACT initiative for chronic pain54 and from the LBP scientific community,55 provide recommendations on how to interpret change scores of core outcome instruments.

Core outcome sets for musculoskeletal conditionsMusculoskeletal disorders are among the most burdensome health conditions, with LBP recognized to be the highest ranked cause of disability worldwide.56 Various health care professionals are routinely involved in managing patients with musculoskeletal conditions and, for example, this is the area in which there are more publications on physical therapy interventions.57 An early COS in this field was proposed by Deyo et al.58 for LBP and included the following five health domains: ‘pain symptoms’, ‘back-related function’, ‘generic well-being’, ‘work-related disability’, and ‘satisfaction with care’, with accompanying measurement instruments.58 An initiative to update this COS was recently undertaken to assess if advancements in COS development methodology and new evidence on domains and instruments would lead to similar recommendations.26 The first phase of this update has been already completed and, through a modified Delphi survey, consensus was reached on the measurement of three core outcome domains: ‘physical functioning’, ‘pain intensity’, and ‘health-related quality of life’.59 The same steering group is currently working around the selection of measurement instruments and recommendations on these will be soon available in the literature. Other initiatives with a different scope and methodology, but always focusing on outcome standardization for LBP, have also reached consensus on the same three core outcome domains to be measured in research and clinical practice.60,61

The IMMPACT initiative has recommended six core outcome domains for clinical trials for chronic pain: ‘pain’, ‘physical functioning’, ‘emotional functioning’, ‘participant ratings of improvement and satisfaction with treatment’, ‘symptoms and adverse events’, and ‘participant disposition’.21 IMMPACT suggested various instruments to measure these domains,62 and specific recommendations for core domains and instruments were also formulated for clinical trials in children with chronic pain.63 A COS for pain following knee replacement was developed by another working group that achieved consensus on eight domains: ‘pain intensity’, ‘pain interference with daily living’, ‘pain and physical functioning’, ‘temporal aspects of pain’, ‘pain description’, ‘use of pain medications’, and ‘improvement and satisfaction with pain relief’.64 Two COSs, one for multidisciplinary rehabilitation22 and one for shoulder disorders65 are currently under development and should be published in the near future. COSs for clinical trials in other pain conditions (e.g. complex regional pain syndrome, neck pain, and post-operative pain management in pediatric patients) are also under development.

Another burdensome and routinely treated musculoskeletal disorder is osteoarthritis (OA),56 for which the OMERACT initiative developed a COS for hip, knee and hand OA clinical trials.66 This COS included three core outcome domains (i.e., ‘pain’, ‘physical function’, ‘patient global assessment’) and an additional one for studies with follow-up longer than one year (i.e. ‘joint imaging’).66 A specific COS for hand OA has been recently developed, with consensus on the first three core domains of the original core set with the addition of ‘joint activity’ and ‘hand strength’.67 The OMERACT recommendation to measure ‘pain’, ‘physical function’, ‘patient global assessment’ has also been taken up by the Osteoarthritis Research Society International (OARSI) guidelines on how to run clinical trials in OA.68,69 These recommendations also added the outcome domain ‘general health status’ and a minimum set of three performance-based tests to assess ‘physical function’ besides patient-reported instruments, as previously agreed in a previous OARSI consensus study.70 For more information on the most suitable instruments for all these domains, readers can refer to read the original manuscripts.

The fact that different working groups have developed COS recommendations in the musculoskeletal pain field led to some overlap regarding the health conditions and interventions covered by the recommendations. For this reason, an attempt to harmonize all these recommendations is needed, first, by establishing the common ground and, second, by clarifying the specialization of each initiative. OMERACT has recently moved toward this direction by creating a pain working group that will attempt to reach consensus on pain domains and measurement instruments.71,72 Additionally, OMERACT and IMMPACT have recently collaborated providing an overview of instruments that can be used to measure ‘physical functioning’ (including aspects of social participation) in chronic pain clinical trials.73 These initiatives are just a starting point to create a broader, international, multidisciplinary group that will work to make consistent and solid minimum COS recommendations for all pain conditions.

Core outcome sets for other conditions and directions for future researchWhile the majority of initiatives around outcomes standardization relevant for rehabilitation is in the musculoskeletal health area, there are also initial attempts to develop COSs in other areas. For example, in the stroke rehabilitation field, while there is already a COS for acute stroke management,74 an international collaboration named as the Stroke Recovery and Rehabilitation Roundtable was recently formed with the goal of standardizing of research and, specifically, also outcomes measurement in clinical trials.75 Researchers or clinicians interested to adopt a COS in their study or clinical practice could further consult the COMET database to evaluate if any COS exists in their area of interest; this database is constantly updated and should include all published COSs for all health conditions and interventions.76 Nevertheless, COSs for rehabilitation interventions targeting disorders other than musculoskeletal are rare. To date, it is unclear if this lack is due to no issues around outcome standardization in clinical trials, or to the limited awareness about the importance and potential of COSs. Hence, researchers working in every health area (e.g., neurology, geriatrics, cardio-respiratory, pediatrics) are encouraged to explore if issues surrounding outcome measurement are present in their field, and to consider if the development of a COS could be useful to improve outcome standardization.

The major challenge in the development of a COS regards its implementation, i.e. how to facilitate the uptake among potential users. Different strategies can be adopted, such as multiple publication, presentations at various international conferences, endorsement by scientific journals and scientific and professional organizations, Cochrane groups, and trial funding agencies, but there is not a standard recipe on how to facilitate a COS acceptance and uptake. There is some evidence to indicate the existence of a COS can improve outcome reporting in clinical trials of rheumatologic conditions,77,78 but there is also some evidence suggesting that COSs have not made an impact.79,80 Research in this area is lacking and it should be put soon in the research agenda of COS methodologists.

ConclusionA COS can facilitate outcomes consistency across studies and consistent reporting in clinical research. Evidence synthesis on the effectiveness of various health interventions could benefit from a wide and structured implementation of COSs in clinical trials. A COS is represented by a set of recommendations regarding core outcome domains and measurement instruments to be measured and reported, thereby not mandating which outcome(s) should be designated as primary outcome in a clinical trial. Consensus on both domains and instruments should optimally be achieved by interdisciplinary groups of different relevant stakeholders, including patients. COS are available in the literature for various musculoskeletal disorders, including LBP, OA and chronic pain, in general. These can be easily implemented by researchers and clinicians to standardize outcome assessment in their research, and may also be relevant for clinical practice. Fewer COSs are available for neurologic, geriatric, cardio-respiratory and pediatric conditions, hence, future research efforts should be directed to identify potential issues around outcome reporting and, if necessary, to develop new COSs.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.