For evidence-based practice, clinicians and researchers can rely on well-conducted randomized clinical trials that exhibit good methodological quality, provide adequate intervention descriptions, and implementation fidelity.

ObjectiveTo assess the description and implementation fidelity of exercise-based interventions in clinical trials for individuals with rotator cuff tears.

MethodsA systematic search was conducted in PubMed, Embase, CINAHL, LILACS, Cochrane Library, Web of Science, SCOPUS and SciELO. Randomized clinical trials that assessed individuals with rotator cuff tears confirmed by imaging exam were included. All individuals must have received an exercise-based treatment. The methodological quality was scored with the Physiotherapy Evidence Database (PEDro) scale. The Template for Intervention Description and Replication (TIDieR) checklist and the National Institutes of Health Behaviour Change Consortium (NIHBCC) were used to assess intervention description and implementation fidelity, respectively.

ResultsA total of 13 studies were included. Despite their adequate methodological quality, the description of the intervention was poor with TIDieR scores ranging from 6 to 15 out of 24 total points. The TIDieR highest-scoring item was item 1 (brief name) that was reported in all studies. Considering fidelity, only one of the five domains of NIHBCC (i.e., treatment design) reached just over 50%.

ConclusionExercise-based interventions used in studies for individuals with rotator cuff tears are poorly reported. The description and fidelity of the intervention need to be better reported to assist clinical decision-making and support evidence-based practice.

Shoulder pain is a very common condition in the general population and may affect up to 66.7% of the population over a lifetime.1 Rotator cuff related shoulder pain, which includes rotator cuff tears, is one of the most frequent diagnoses.2–4 Current evidence shows that surgical approaches are not superior to conservative approaches, and that exercise-based treatment should be considered as a first-line option.5,6

The effectiveness of exercise-based interventions in individuals with rotator cuff tears has been previously reported.5–7 It is therefore timely to assess the description and implementation fidelity of clinical trials investigating exercise-based interventions for rotator cuff tears. Incomplete reporting of interventions may prevent clinicians and researchers to promptly replicate these interventions in clinical practice and future trials.

The Template for Intervention Description and Replication (TIDieR) can be used to improve the description of interventions and their implementation. The TIDieR checklist was created in 2014 to improve reporting of interventions in clinical trials.8,9 This checklist contains 12 items that cover information about how a treatment is delivered, the equipment and the level of training needed, and the dose and intensity used in the program, among others.10 In addition to providing a detailed description of an intervention, implementation fidelity of the intervention is another aspect that may improve reliability and internal validity of the study, as it involves the knowledge of the fidelity between what was prescribed compared to what was performed as an intervention in the trial.11 If studies do not provide enough and adequate details about the intervention, the findings may be under or overestimated, resulting in misleading interpretations and hindering reproducibility for researchers and clinicians.12 The National Institutes of Health Behaviour Change Consortium (NIHBCC)13 was created to assess the implementation fidelity and improve the clarity and quality of reporting interventions. This tool evaluates the full treatment implementation model that consists of treatment delivery, receipt, and enactment.14,15 Ideally, clinicians and researchers should be able to replicate evidence-based exercises to treat individuals with shoulder pain and rotator cuff tear. Therefore, it is important that studies not only have low risk of bias, but also provide information about materials, infrastructure, dosage, possible modifications made in the treatment, and appropriate implementation fidelity.

The objective of this study was to assess the description and implementation fidelity of exercise-based interventions in clinical trials for individuals with rotator cuff tears. We expected to highlight possible gaps for clinicians and researchers.

MethodsRegistration and research questionThis scoping review was previously registered in Open Science Framework on March 31, 2022 (https://osf.io/xv3cq). The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses Extension for Scoping Review (PRISMA-ScR) guideline was followed.16

Data sources and searchA systematic search was conducted in 8 electronic databases (PubMed, Embase, CINAHL, LILACS, Cochrane Library, Web of Science, SCOPUS and SciELO) from their inception to June 2023. These databases, including regional ones, were searched in an attempt to conduct a comprehensive search and identify as much relevant evidence as possible. A search strategy was developed by combining relevant keywords. All keywords were searched independently and then combined using relevant Boolean terms. Randomized clinical trials were selected and no other limits were used (Supplementary material).

Study eligibilityIn this review, inclusion criteria were determined based on the “PCC” mnemonic which stands for Population, Concept, and Context.17 Population: Individuals with a partial or full-thickness rotator cuff tear confirmed by imaging exam. The tear size was not taken into consideration as long as the articles did not exclusively include a population with massive and irreparable rotator cuff tears. Concept: The target population included individuals who received an exercise-based treatment in any study arm. Exercise-based interventions were considered when any type of exercise was applied alone or as a component of a rehabilitation program, which could also include other therapeutic modalities such as electrotherapy, medication, pain education, injection, and other interventions combined with exercise. Context: This scoping review focused on randomized clinical trials (RCT).

Studies that involved participants with shoulder pain and other diagnoses, for example an isolated tendinopathy in rotator cuff muscles or bursitis (mixed population), shoulder instability, and/or frozen shoulder were excluded. Retrospective studies, cohort studies, case studies, clinical commentaries, recommendation papers, and consensus statements were also excluded.

Data extractionTwo independent reviewers (LPR and FCM) performed the selection process and a third reviewer (FAS) was consulted for consensus in case of any disagreement. Articles were analyzed with the assistance of the StArt program (copyright_version) designed by the Universidade Federal de São Carlos (Brazil). The titles were initially screened and those that clearly did not fit the eligibility criteria were excluded. The abstracts of the selected titles were analyzed for inclusion according to the study design, participants, and interventions. Finally, the full texts of potentially relevant articles were analyzed for inclusion. Reference lists from included full-text articles and retrieved systematic reviews were also screened for additional relevant publications.

Data itemsTo characterize the articles, information about the year of publication, number of participants, diagnosis, type of injury, and outcomes evaluated in each article was collected. Furthermore, all articles were assessed according to the scale and checklists below.

Methodological quality assessmentAll studies were scored with the Physiotherapy Evidence Database (PEDro) scale, which is a tool that evaluates the risk of bias and completeness of statistical reporting of trial reports for interventional studies in physical therapy.18 PEDro is a reliable tool and the items are scored as yes (1) or no (0). It consists of 11 items, but it is important to note that item 1 is not scored.19 Thus, the possible maximum score is 10 points. If an item was not clearly described or unclear, no points were awarded. The scoring can be classified as "poor" (less than 4 points), "fair" (4–5 points), "good" (6–8 points), and "excellent" (9–10 points).20 The scores of the studies already indexed and scored in the PEDro database were used. Methodological quality assessment of studies not indexed in PEDro was performed by two independent reviewers (LPR and FCM). Any inconsistency in the rating was solved by a third reviewer (FAS).

TIDieR checklistThe TIDieR checklist consists of 12 items: (1) brief name, (2) why, (3) what materials, (4) what procedures, (5) who provided, (6) how, (7) where, (8) when and how much, (9) tailoring, (10) modifications, (11) how well (planned), and (12) how well (actual).8 Each item was scored using the following criteria: reported (2), partially reported (1), not reported (0). The range of score varies from 0 to 24 points. This tool is valid and used to improve description of interventions in clinical trials.12,21–23 The TIDier assessment was performed by two independent reviewers (LPR and FCM) and inconsistencies in rating were solved by a third reviewer (FAS).

NIHBCC checklistThe NIHBCC checklist has five domains: (1) treatment design, (2) training of providers, (3) treatment delivery, (4) treatment receipt and (5) treatment enactment.24 In general, the checklist helps to understand how the intervention was designed, as well as if and how healthcare professionals were trained, how the treatment was delivered to the patient, how the patient received it, and the execution of what was proposed. The NIHBCC assessment was performed by the same researchers (LPR and FCM). Each item was scored using the following criteria: reported (2), partially reported (1), not reported (0) and NA, when “not applicable”. In the treatment design domain, there is a total of six questions. The maximum and minimum scores depend on the number of intervention groups. Specifically, when the study includes more than two treatment groups, the score can reach higher values because it requires evaluating the information from each group. The maximum score in the training of providers domain was 14 points with seven questions, treatment delivery was 18 points with nine questions, treatment receipt was 10 points with five questions, and treatment enactment was 4 points with only two questions.24 This checklist was previously used in other studies involving exercise intervention.12,25

Synthesis of resultsExtracted data were organized in Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA) where scores and percentages were calculated. The scale and checklist's items were classified in a consensus forum between LPR and FMC.

ResultsOur database search identified 4400 articles. Thirteen studies fulfilled the criteria for inclusion with a total of 900 participants. A flow chart with the selection process is shown in Fig. 1. The characteristics of the included studies are provided in Table 1. Two follow-up studies reporting secondary analyses for different time points from the same trial in separate publications,26–29 were merged and presented in this review as a single study.30,31

Characteristics of the included studies.

| Article | Year of Publication | Population | Diagnosis | Atraumatic, Traumatic or Both | Intervention | Outcomes | PEDro Scale |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hajivandi et al32 | 2021 | n = 96 | Full-thickness rotator cuff degenerative tear | Atraumatic | EBT + CSI x EBT x CSI | VAS, ROM, DASH | 4/10 |

| Sadikoglu et al33 | 2021 | n = 46 | Partial-thickness rotator cuff tears | – | Ischemic compression + EBT x IASTM + EBT | DASH, ASES, VAS, ROM, PPT, HADS and Global Rating of Change scale | 7/10 |

| Centeno et al34 | 2020 | n = 25 | Partial or full-thickness rotator cuff tear | – | EBT x Injection | DASH, NPS, SANE | 6/10 |

| Ranebo et al35 | 2020 | n = 58 | Full-thickness rotator cuff tear | Traumatic | Surgery x EBT | CSM, strength, WORC, NRS, MRI | 8/10 |

| Türkmen et al36 | 2020 | n = 33 | Partial-thickness rotator cuff tear | – | EBT (video) x EBT-(supervised) | ROM, VAS, DASH, ASES, PCS-12, MCS-12, Global Rating of Change scale | 7/10 |

| Akbaba et al37 | 2019 | n = 53 | Partial-thickness rotator cuff tears | – | Myofascial trigger points + EBT x EBT | VAS, ROM, DASH, ASES, and HAD | 8/10 |

| Vrouva et al38 | 2019 | n = 42 | Partial-thickness rotator cuff tear | – | TENS + EBT x MENS + EBT | SPADI, NRS, EQ-5D | 6/10 |

| Kim et al39 | 2018 | n = 78 | Partial-thickness rotator cuff tears | Atraumatic | Immediate repair x delayed repair after EBT | ASES, CSM, ROM, VAS, repair integrity | 4/10 |

| Heerspink et al40 | 2015 | n = 56 | Full-thickness rotator cuff tear | Atraumatic | Surgery x EBT | CMS, DSST, VAS Radiologic Outcome | 6/10 |

| Ilhanli et al41 | 2015 | n = 70 | Partial-thickness supraspinatus tear | – | Platelet-rich plasma x EBT | ROM, VAS, DASH | 5/10 |

| Kukkonen et al28,29,31 | 2014, 2015 and 2021 | n = 180 | Symptomatic supraspinatus tendon tear comprising < 75% of the tendon | Atraumatic | EBT x Acromioplasty + EBT x Repair + acromioplasty + EBT | CSM | 7/10 |

| Gialanella et al42 | 2011 | n = 60 | Full-thickness rotator cuff tear | – | Single injection x Two injections x EBT | VAS, CMS | 5/10 |

| Moonsmayer et al26,27,30 | 2010, 2014 and 2019 | n = 103 | Symptomatic small or medium-sized partial-thickness tears of the rotator cuff | Both | Surgery x EBT | CMS, ASES score, SF-36 | 8/10 |

ASES, American Society of Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons; CMS, Constant-Murley Score; CSI, corticosteroid injections; DASH, Disabilities of Arm, Shoulder and Hand; DSST, Dutch Simple Shoulder Test; EBT, exercise-based treatment; EQ-5D, EuroQoL Questionnaire; IASTM, instrument-assisted soft tissue mobilization; NPS, numerical pain scale; NRS, numerical rating scale; ROM, range of Motion; SANE, Single Assessment Numeric Evaluation; SF-12, Short Form 12; SPADI, Shoulder Pain and Disability Index; VAS, visual analogic scale.

Among the included studies, the oldest article was published in 2010, and the most recent ones were published in 2021. Most studies included individuals with partial-thickness tears rather than full-thickness rotator cuff tears, and the mechanism of injury varied but was mostly not reported. Several approaches were used in the management of individuals with rotator cuff tears. In addition to exercises, the treatment also involved injection therapy, manual therapy, electrotherapy, and shoulder surgical procedures. The outcome measures used to assess effectiveness were highly variable. Shoulder function and pain were evaluated in all studies (n = 13), but using different tools. Muscle strength (n = 6),30,31,35,39,40,42 range of motion (n = 8),30–32,35,37,39,40,42 radiological outcomes (n = 3),29,35,40 pressure pain threshold (n = 1),33 and satisfaction (n = 2)33,36 were also evaluated in some studies. Psychosocial (n = 3)30,35,38 and psychological (n = 2)33,37 factors were assessed in a few studies. The mean PEDro score was, on average, 6.2/10 (standard deviation [SD]: 1.3) indicating a good methodological quality of the articles included (Table 1).

The TIDieR scores are provided in Table 2. The average score across all studies on the TIDieR was 10.4/24 (SD: 2.6) points, ranging from 6 to 15 points. The percentage regarding each TIDieR item checklist varied from 7.6% (lowest value achieved) to 100% (highest value achieved) and are presented in Table 3. All studies (n = 13) provided information about the first item (brief name that provided the name or a phrase that described the intervention). Few studies reported possible adaptations in the management (n = 4)26,27,30,40 and adherence (n = 2)32,35 to the program (Table 3).

Template for Intervention Description and Replication (TIDieR) score, score of each item and total score, for the included studies.

Score for item 1 to 12 and overall TIDieR score. Green, item was reported (2 points); yellow, item was partially reported (1 point); red, item was not reported (0 point).

Overall score and percentage of studies reporting items from Template for Intervention Description and Replication (TIDieR) checklist (n = 13).

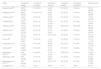

Regarding implementation fidelity across the NIHBCC scale, the overall fidelity score across all the studies (n = 13) of each domain ranged from 0.5 to 51.2%. The highest score was for treatment design domain that reached 51.2%, and the lowest scores were in the domains of training of providers and treatment enactment, which scored 0.5% and 3.8%, respectively. The treatment delivery and treatment enactment also achieved low final scores, 20.8% and 3.8%, respectively. The overall score of all studies with the five domains taken together was 27.4%. All information about NIHBCC score is presented in Table 4 with the score of each article.

The National Institutes of Health Behaviour Change Consortium (NIHBCC) score.

| Article | Treatment design | Training of providers | Treatment delivery | Treatment receipt | Treatment enactment | Overall score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hajivandi et al32 | 65.0% (26/40) | 0% (0/14) | 16.6% (3/18) | 0% (0/10) | 0% (0/4) | 33.7% (29/86) |

| Sadikoglu et al33 | 68.8% (22/32) | 7.4% (1/14) | 16.6% (3/18) | 0% (0/10) | 0% (0/4) | 33.3% (26/78) |

| Centeno et al34 | 34.3% (11/32) | 0% (0/14) | 16.6% (3/18) | 0% (0/10) | 0% (0/4) | 17.9% (14/78) |

| Ranebo et al35 | 59.3% (19/32) | 0% (0/14) | 55.5% (10/18) | 0% (0/10) | 0% (0/4) | 37.1% (29/78) |

| Türkmen et al36 | 71.8% (23/32) | 0% (0/14) | 38.8% (7/18) | 60% (6/10) | 50% (2/4) | 48.7% (38/78) |

| Akbaba et al37 | 59.4% (19/32) | 0% (0/14) | 27.7% (5/18) | 0% (0/10) | 0% (0/4) | 30.8% (24/78) |

| Vrouva et al38 | 53.1% (17/32) | 0% (0/14) | 5.5% (1/18) | 0% (0/10) | 0% (0/4) | 23.1% (18/78) |

| Kim et al39 | 28.1% (9/32) | 0% (0/14) | 11.1% (2/18) | 0% (0/10) | 0% (0/4) | 14.1% (11/78) |

| Heerspink et al40 | 53.1% (17/32) | 0% (0/14) | 22.2% (4/18) | 0% (0/10) | 0% (0/4) | 26.9% (21/78) |

| Ilhanli et al41 | 46.8% (15/32) | 0% (0/14) | 11.1% (2/18) | 0% (0/10) | 0% (0/4) | 21.8% (17/78) |

| Kukkonen et al28,29,31 | 30% (12/40) | 0% (0/14) | 11.1% (2/18) | 20% (2/10) | 0% (0/4) | 18.6% (16/86) |

| Gialanella et al42 | 45% (18/40) | 0% (0/14) | 33.3% (6/18) | 0% (0/10) | 0% (0/4) | 27.9% (24/86) |

| Moonsmayer et al26,27,30 | 50% (16/32) | 0% (0/14) | 5.5% (1/18) | 0% (0/10) | 0% (0/4) | 21.8% (17/78) |

| Average score | 51.2% | 0.5% | 20.8% | 6.1% | 3.8% | 27.4% |

This review evaluated the description and implementation fidelity of exercise-based interventions included in clinical trials for individuals with rotator cuff tears. Our findings show these clinical trials showed good methodological quality, but the description and fidelity of the intervention were poorly reported. Clinicians and researchers may face challenges when attempting to replicate and implement the interventions due to insufficient available information.

Most of the included clinical trials were published in 2018 or after. Even after the publication of the TIDieR checklist in 2014, few items were properly reported in more recent studies, making it difficult to replicate the intervention. Interventions performed in individuals with rotator cuff tear were highly variable. Studies compared exercises versus surgery,30,31,35,39,40 different exercises modalities36 or exercises associated with manual therapy33,37 or electrotherapy38 and also injectable therapies.32,34,41,42

The average quality of the included studies was considered “good” based on an overall mean score greater than 6 points on the PEDro scale.43 While the PEDro scale is a valid tool to assess the methodological quality of clinical trials,44 and the studies are of good quality, the lack of information hinders the implementation of the intervention. Full treatment description would allow replication of the intervention,8 while incomplete information creates a barrier in the implementation of potential effective treatments.10 The results of this study show a lack of information about interventions because the low total TIDieR scores indicate a lack of information even in those studies recently published.32–39,45 Missing information included treatment duration, dose, intensity, intervention planning, and modifications, as well as patient adherence to the program.

Clinicians treating individuals with shoulder pain and rotator cuff tears, researchers conducting trials with this population and also for policymakers interested in implementing evidence-based interventions may face challenges when trying to use interventions included in this review. Patients may not adhere to exercise interventions or opt for other approaches such as surgical procedure, medications, or injectable therapies due to a lack of clarity about, for instance, exercise progression or adaptations. Our findings are in agreement with other studies involving physical therapy treatment in patients with hip osteoarthritis,22 femoroacetabular impingement syndrome,46 subacromial pain syndrome,12 hamstring strain,21 Achilles tendon rupture,47 and preoperative patient program for orthopaedic surgery48 where researchers also need to improve the quality of reporting interventions.

In general, the evaluation of fidelity of studies involving individuals with rotator cuff tear was low. As in previous studies,12,25 the lowest scored domain was training of providers, meaning that no detailed information about how the training was conducted, the assessment of skill acquisition, and whether any specific characteristics were encouraged or avoided during the sessions. Non-significant results of a treatment can potentially be attributed to ineffectiveness of an intervention or also by providers with inadequate training and monitoring.24 In addition, the patient's skills during the exercises should be assessed and informed. It is also important to minimize the chances of the patient not performing or performing the exercise incorrectly when not supervised.

A clinical trial is often considered a high-impact publication. However, detailing the implementation process is essential to understand possible barriers and facilitators of an intervention program. Over the years, authors have been striving to minimize bias and improve the methodological quality of clinical trials.49 However, improving the quality of information is also important, and can impact the ability to replicate the intervention, especially in clinical practice. Although it is easier to think about the importance of designing and delivering the treatment, it is also necessary to train professionals, and to understand how the patient receives and executes the intervention. Therefore, future studies need to improve the quality of reporting interventions, and scientific journals should request authors to report each step of the intervention more clearly, facilitating its replication and implementation. It is possible that improving the understanding and execution of the exercise program leads to greater adherence to treatment. Through good fidelity delivery, it is possible to improve evidence-based practice and assist the clinicians in decision making.50

LimitationsThis study has some limitations. Some of the items of the NIHBCC may have influenced the final score. For instance, the item regarding the method to ensure dose equivalence between intervention groups was rated as "not applicable" in all articles, which removes this item from the final score in the treatment design domain. In contrast, for studies comparing similar exercises without the addition of other modalities or treatments this item was relevant and included in the final score. In addition, it is possible that the authors may have provided an item, as for example, advice or education, but did not mention that in the manuscript. There are no methods to weight or infer if it was done unless it was explicitly mentioned, resulting in a reduction of the total score.

ConclusionExercise-based treatment in individuals with rotator cuff tears presents poor description and fidelity of the interventions. More information about the infrastructure, adaptations during the treatment and adherence are needed to improve the description of the treatment. In addition, information about provider training is essential. Future studies should improve the treatment description and fidelity in attempt to facilitate implementation by clinicians, researchers, and policymakers and replication of the study.

Data sharingAll data relevant to the study are included in the article or are available as supplementary material.

This project was funded by Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES), Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq) (144436/2019-1) and Erasmus+ (63350-MOB-00143). The funders had no role in study design, data analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.