Sarcopenia, characterized by the progressive loss of muscle mass and function, is exacerbated in older adults with cardiovascular diseases. In hospitalized older adults, quick and practical questionnaires such as the SARC-F and SARCCalF are important for early risk screening and help guide effective interventions.

ObjectiveTo identify the prevalence of sarcopenia and sarcopenia risk, and to assess the diagnostic accuracy of the SARC-F and SARCCalF questionnaires in screening for probable and confirmed sarcopenia.

MethodsCross-sectional study with older adults admitted to the emergency department of a public hospital for cardiovascular diseases between January and September 2023. Sarcopenia was assessed based on muscle strength (handgrip dynamometry), muscle mass (calf circumference), and physical performance (gait speed). The risk of sarcopenia was estimated using the SARC-F and SARCCalF questionnaires. Statistical analyses included Mann-Whitney U tests and ROC curves.

ResultsIn a sample of 160 participants, the prevalence of sarcopenia was 21.3%. The SARCCalF identified 42.5 % of older adults at risk and the SARC-F 32.5 %. The SARCCalF demonstrated greater accuracy in identifying confirmed sarcopenia (AUC=0.85 [95%CI: 0.79, 0.91]) and low muscle strength (AUC=0.71 [95%CI: 0.62, 0.79]) when compared to the SARC-F.

ConclusionThe prevalence of sarcopenia was lower than expected in the study population. The SARCCalF was better able to identify older adults at risk of sarcopenia and demonstrated greater diagnostic accuracy than the SARC-F in detecting probable and confirmed sarcopenia, standing out as a more effective screening tool for this population.

Sarcopenia is characterized by a progressive and generalized loss of muscle mass and function, typically associated with ageing, and an increased risk of adverse events such as falls, fractures, cognitive impairment, disability, and mortality.1,2 In addition to affecting metabolism, sarcopenia negatively influences the body’s immunological and inflammatory responses.

In people with chronic disorders such as cardiovascular diseases (CVDs), it can exacerbate catabolic factors associated with these comorbidities, intensifying skeletal muscle dysfunction, thereby making the condition more severe.3,4 Factors such as malnutrition, inflammation, oxidative stress, sedentarism and insulin resistance are common to both sarcopenia and cardiac disorders and contribute to their development and progression.4

The prevalence of sarcopenia ranges from 10 to 16 % in older adults,2 35 % in older adults with CVDs,5 and 44 % in those hospitalized for cardiovascular disorders.6 It is initially diagnosed based on poor muscle strength (probable sarcopenia) and confirmed by concomitant low muscle mass. Sarcopenia is classified as severe when poor muscle strength, low muscle mass, and impaired physical performance are present.1 According to the European Working Group on Sarcopenia in Older People 2 (EWGSOP2), muscle strength can be assessed using the chair stand (CST) and handgrip strength (HGS) tests. Muscle mass can be evaluated using a variety of methods, the most widely recommended being dual energy X-ray absorptiometry (DEXA) and bioelectrical impedance analysis (BIA). Physical performance is measured by tests such as gait speed, the Short Physical Performance Battery (SPPB), timed up and go (TUG), and 400-meter walk test, the last used to determine sarcopenia severity.1

Despite the high prevalence of sarcopenia among older adults hospitalized for CVDs, functional assessment in this setting is challenging due to physical limitations such as swelling, chest pain, and breathing difficulties. Moreover, handgrip dynamometers are often unavailable in most hospital admission settings, further limiting the feasibility of muscle strength assessment. These barriers hinder the routine application of physical tests for sarcopenia diagnosis in hospitals.7,8 Screening for the risk of sarcopenia (particularly probable and confirmed sarcopenia) is clinically relevant because older adults with CVDs frequently present with reduced muscle strength, making them more susceptible to developing severe weakness and cardiac cachexia, which are associated with worse outcomes such as hospital readmission and mortality. Therefore, early identification and active intervention are vital to improve prognosis in this population.8

The self-report SARC-F and SARCCalF questionnaires stand out as alternative screening tools for sarcopenia risk to overcome the difficulties of assessing hospitalized older adults. The SARC-F contains five questions that assess older adults’ perceptions of their limitations in terms of strength, walking ability, rising from a chair, climbing stairs, and history of falls.1 The SARCCalF was developed to complement the SARC-F and includes calf circumference, an easily obtained and low-cost anthropometric measurement.9 Recent studies indicate moderate to high specificity for both questionnaires, with the SARCCalF exhibiting greater sensitivity than the SARC-F.10–19

However, the diagnostic accuracy of these questionnaires has yet to be compared in older adults hospitalized with cardiac diseases. There is a need to investigate the efficacy of these tools in this specific population, given the particularities of cardiovascular comorbidities, such as swelling of the lower limbs frequently observed in older adults with chronic heart failure (CHF).8 The present study aimed to identify the prevalence of sarcopenia and sarcopenia risk, and to assess the diagnostic accuracy of the SARC-F and SARCCalF questionnaires in screening for probable and confirmed sarcopenia in older adults hospitalized with cardiovascular diseases.

MethodsStudy designThis is a secondary analysis using information from the database compiled by the study entitled “Association between SARC-F and clinical outcomes in older adults admitted to the emergency room with cardiovascular diseases”.20 The present study is an observational cross-sectional investigation conducted at the Hospital de Base do Distrito Federal, with older adults treated in the neurology and cardiology emergency room of the Neurocardiovascular Center (CNCV), including only those admitted to the Cardiology Department with acute heart failure. Data were collected between January and September 2023. The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committees of the University of Brasilia’s Faculty of Health Sciences and Technologies (UnB) and the Institute of Strategic Health Management of the Federal District (IGESDF) (protocol number 5.863.099). All participants gave written informed consent.

ParticipantsThe study included older adults (aged ≥ 60 years) of both sexes, with CVDs such as heart failure, systemic hypertension, heart valve disorders, coronary artery disease, and arrhythmias, admitted to the emergency room of Hospital de Base do Distrito Federal. Participants were selected based on their ability to cooperate with the assessment, measured by the Standardized Five Questions (S5Q) score,21 which requires older adults to be able to comply with at least three of the five S5Q commands: open and close your eyes, look at me, open your mouth and stick out your tongue, nod your head, and raise your eyebrows after I have counted to five.

Older adults were excluded if they had contraindications to performing two or more tests due to the severity of their underlying condition, were using vasoactive or inotropic drugs, or presented with chest pain, hemodynamic instability (defined as systolic blood pressure [SBP] > 160 or 〈 80 mmHg and heart rate [HR] < 50 or 〉 120 bpm), hemiparesis/hemiplegia, paraparesis/paraplegia, or had limb amputations.

Sample sizeThis study involved a secondary analysis of data from a main study, in which sample size was estimated using GPower 3.1.5 software. The estimate was based on the odds ratio (OR) reported by Xu et al. (OR= 2.61 [95 %CI: 1.71, 3.98]) for the association between sarcopenia and in-hospital mortality.22 Considering logistic regression with an OR of 2.61, statistical power of 95 % and alpha error of 0.05, the required sample size was 101 older adults. The final sample size was increased to avoid issues relating to underpowering.

Characterization variablesStudy participants were characterized based on demographic variables including sex (male or female), age (full years), and education level (years of schooling).

The clinical variables evaluated were continuous use of medication (amount), body mass index (BMI), clinical diagnosis (heart failure - HF, arrhythmias, heart valve disorders, coronary artery disease – CAD, aortic diseases, pericardial effusion), comorbidities (metabolic, kidney, respiratory and oncological disorders and other CVDs), and smoking history (current smoker, ex-smoker or nonsmoker).

Risk of sarcopeniaRisk of sarcopenia was the independent variable in this study, evaluated by the SARC-F and SARCCalF questionnaires.9

The SARC-F contains five questions that address muscle strength, the need for assistance when walking, ability to rise from a chair, climbing stairs, and frequency of falls, each scored from 0 to 2, with a maximum total score of 10 points. Older adults who scored ≥4 were classified as at risk of sarcopenia.9

The SARCCalF contains six items, namely the five SARC-F questions and calf circumference measurement, with 10 points allocated for a circumference ≤ 33 cm in women and ≤ 34 cm in men. Participants were classified as at risk of sarcopenia when their total score was ≥ 11.9

Muscle strengthMuscle strength was determined based on handgrip strength (HGS), assessed by handgrip dynamometry (HGD) using a Saehan® dynamometer (Saehan Corporation, 973, Yangdeok-Dong, Masan, South Korea). Participants were lying in bed in a semi-recumbent position (head raised between 45 and 60°), elbow flexed at 90°, forearm in a neutral position and wrists extended.23,24 Three measurements were taken on the dominant arm, with older adults verbally encouraged to squeeze as hard as possible for 6 s, with a 1-minute interval between attempts. The average of the three attempts was recorded. Values below 16 kgf in women and 27 kgf in men were classified as low HGS, which is considered indicative of probable sarcopenia according to the European consensus.1

Muscle massMuscle mass was established via calf circumference (CC), in accordance with Cruz-Jentoft et al.1 Measurement was on the non-dominant lower limb, with participants lying in bed in dorsal decubitus, their foot resting on the bed and knee flexed, forming a right angle with their thigh. A plastic measuring tape was used, at the widest point of the calf,25 with values ≤ 33 cm classified as low muscle mass in women and ≤ 34 cm in men, according to cutoff points established for older adults in Brazil.26

Physical performancePhysical performance was evaluated by the 4-meter walk test (4MWT), performed on a flat surface, with the beginning and end of the 4-meter course marked by tape. Participants were instructed to walk at their “normal speed” as soon as they heard the word “go”, with walking speed calculated by dividing the 4-meter distance by the time in seconds. For analyses, gait speed was considered a continuous numerical variable and participants with speeds ≤ 0.8 m/s were classified as exhibiting poor physical performance.1

Confirmed sarcopenia diagnosisIn accordance with the guidelines of the European Working Group on Sarcopenia in Older People 2 (EWGSOP2), participants were classified as follows: probable sarcopenia, in the event of low muscle strength; confirmed sarcopenia, for low muscle strength and mass; and severe sarcopenia when low muscle strength, low muscle mass, and poor physical performance were present.1 After diagnosis, they were divided into two subgroups: nonsarcopenic, for those with probable or no sarcopenia, and sarcopenic, for participants with confirmed or severe sarcopenia.

Data analysisSARC-F and SARCCalF scores were compared between nonsarcopenic and sarcopenic subgroups using the Mann-Whitney U test. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were constructed to evaluate the ability of the SARC-F and SARCCalF questionnaires to discriminate between older adults with and without confirmed sarcopenia, as well as those with and without low muscle strength (probable sarcopenia). The area under the ROC curves (AUC), with 95 % confidence intervals, was calculated for each curve. AUCs between 0.51 and 0.69 indicated poor discrimination and values greater than 0.70 satisfactory discrimination.27 Data normality was assessed by the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Significance was set at 5 %. All the statistical analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 29.0.

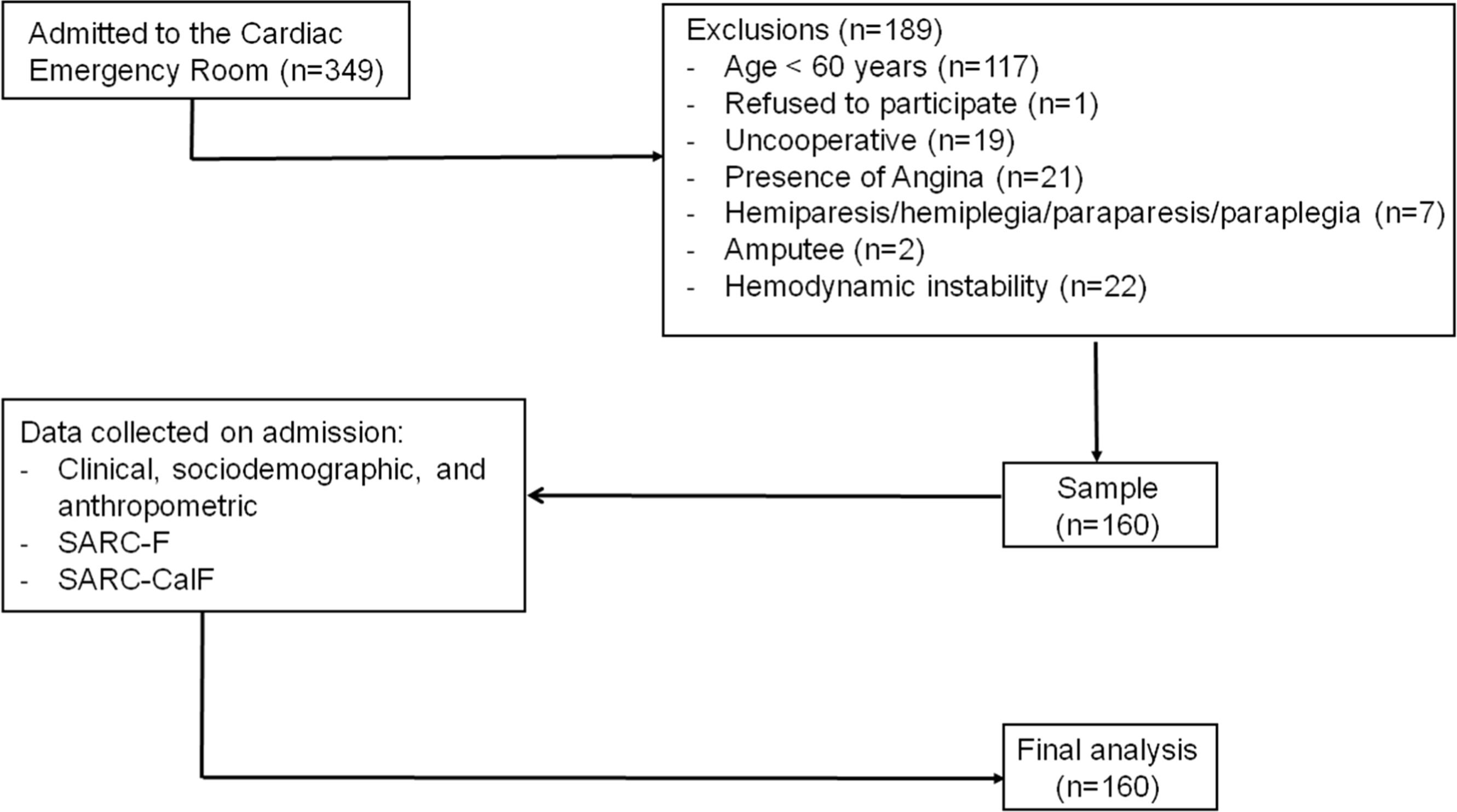

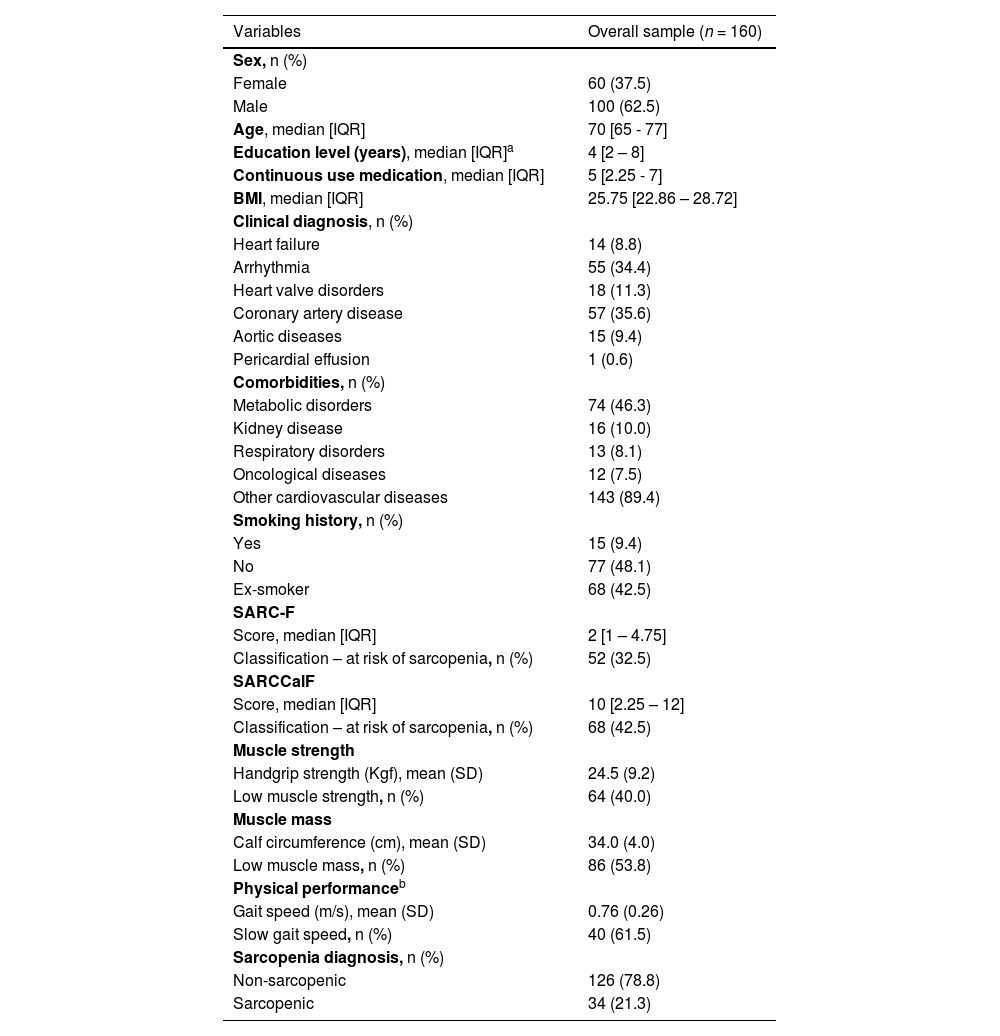

ResultsDuring the data collection period, 349 patients with cardiac conditions were admitted and assessed for eligibility. Of these, 189 were excluded for not meeting the inclusion criteria or refusing to take part. Thus, analyses were carried with 160 participants (Fig. 1). All participants completed the questionnaires and underwent HGS and CC assessments. Gait speed testing was conducted in 65 participants; the remaining participants were temporarily unable to perform the test due to a medical prescription of absolute rest at hospital admission. Most of the participants were men (62.5 %), with a median age of 70 years [IQR: 65 - 77] and median of 4 years of schooling [IQR: 2 - 8] (Table 1).

Participant characteristics on admission.

BMI: body mass index (kg/m2.

On admission to the hospital, the prevalence of sarcopenia risk was 32.5 and 42.5 % according to the SARC-F and SARCCalF, respectively. In relation to the specific sarcopenia parameters, 40 % of participants exhibited low muscle strength (probable sarcopenia), 53.8 % low muscle mass, and 61.5 % poor physical performance. Based on these criteria, 21.3 % were classified as confirmed sarcopenic (confirmed or severe sarcopenia) (Table 1).

In relation to the SARC-F components (Fig. 2), most participants experienced no difficulty with the activities evaluated. Among the risks identified, the most prevalent was difficulty and/or inability to climb stairs (58.1 %), followed by smaller calf circumference (53.7 %), difficulty lifting and carrying a weight of 5 kg (48.8 %), history of falls (36.9 %), rising from a bed or chair (36.3 %), and walking across a room (32.5 %).

A comparison of SARC-F and SARCCalF scores between the subgroups is presented in Fig. 3. There were no significant differences in SARC-F scores between older adults with normal and low muscle strength (probable sarcopenia), nor between those with and without confirmed sarcopenia. However, SARCCalF scores were significantly higher (indicating greater risk of sarcopenia) among older adults with low muscle strength (probable sarcopenia) compared to those with normal strength, and also among those with confirmed sarcopenia compared to older adults without confirmed sarcopenia.

In analyses of the ROC curves (Fig. 4), AUCs of SARC-F scores were not significant in identifying low muscle strength (probable sarcopenia) and confirmed sarcopenia (p > 0.05). By contrast, AUCs of SARCCalF scores were significant in detecting low muscle strength (AUC = 0.71 [95 %CI: 0.62, 0.79; p < 0.001 and confirmed sarcopenia (AUC = 0.854 [95 %CI: 0.79, 0.91; p < 0.001].

DiscussionIdentifying sarcopenia in hospital settings is an important step in guiding rehabilitation and counter-referral interventions. This study aimed to identify the prevalence and risk of sarcopenia in older adults hospitalized with CVDs, and to assess the accuracy of the SARC-F and SARCCalF questionnaires in detecting probable and confirmed sarcopenia. The results indicated that these older adults already exhibit impaired muscle strength and physical function on admission, with 58.1 % experiencing difficulty climbing stairs, 53.7 % low muscle mass, 48.8 % unable to lift a weight of 5 kg, 36.9 % a history of falls, 36.3 % difficulty rising from a bed or chair, 32.5 % problems walking across a room unaided, and 21.3 % diagnosed with sarcopenia. The SARCCalF questionnaire was better able to identify older adults at risk of sarcopenia with greater prevalence and accuracy than the SARC-F and proved to be better suited to screening these older adults.

The prevalence of sarcopenia risk was 42.5 % on the SARCCalF and 32.5 % according to the SARC-F, corroborating previous studies in which SARCCalF consistently identified a higher proportion of older adults at risk compared to the SARC-F.10–12,14–19,28 Regarding the prevalence of confirmed sarcopenia, the 21.3 % found in our study was lower than expected. Although this value is higher than the prevalence reported for the general older population (10 %−16 %),2 it remains below estimates found in older adults with CVDs (35 %)5 and those hospitalized with cardiovascular conditions (44 %).6 However, the systematic review6 reporting this 44 % prevalence described a wide range of values (11.9 % to 68 %), reflecting heterogeneity in study populations, the types and severity of CVDs, and differences in diagnostic methods6 and criteria used across studies. Notably, our assessments were conducted upon hospital admission in an emergency department setting, whereas some studies perform assessments at discharge, a time when patients may already exhibit muscle loss related to hospitalization. These methodological and clinical differences may explain the lower prevalence observed in our sample and should be considered when comparing findings across studies.

The present study demonstrated that the SARCCalF exhibited good diagnostic accuracy for screening sarcopenia in older adults hospitalized with CVDs. Comparative analyses indicated that older adults with low muscle strength and those with confirmed sarcopenia obtained significantly higher SARCCalF scores than those without sarcopenia. The SARCCalF correctly identified 71 % of cases with low muscle strength (probable sarcopenia) and 85 % with confirmed sarcopenia, while the SARC-F was unable to satisfactorily differentiate sarcopenia. These results are in line with previous investigations that demonstrate the superiority of the SARCCalF in different populations, including a study to validate the questionnaire,9 research with community-dwelling older adults10,15 and people with diabetes.19

These findings are particularly relevant for older adults hospitalized with CVDs, because confirmed sarcopenia is associated with severe complications, such as higher mortality and prolonged hospital stays, which may exacerbate the clinical picture of CVDs and result in worse health outcomes.2,6 A strong point of the present study is the fact that it was conducted in an emergency room, where older adults admitted for CVD exacerbation have difficulty performing physical tests. This complex clinical scenario reinforces the relevance of the findings, because older adults in critical condition are challenged to undergo sarcopenia assessment. Moreover, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to compare the diagnostic accuracy of the SARC-F and SARCCalF questionnaires in older adults hospitalized with CVDs. Early screening for muscle weakness and sarcopenia at hospital admission enables more targeted interventions during hospitalization and improve the clinical prognosis.6 Additionally, in-hospital sarcopenia screening facilitates counter-referral to primary care, ensuring the continuity and comprehensiveness of care.29

Despite the relevant findings, this study also has some limitations. The main limitation concerns the methodological overlap between the sarcopenia diagnostic reference and the SARCCalF questionnaire, as both rely on calf circumference to estimate muscle mass. This overlap may have introduced measurement bias, potentially overestimating the diagnostic performance of the tool. Nevertheless, in our study, the SARCCalf demonstrated good discriminatory ability not only for confirmed sarcopenia (which includes calf circumference in its definition), but also for probable sarcopenia, which is based solely on muscle strength. Additionally, calf circumference may have limited accuracy in certain clinical conditions. In obese older adults, excess adipose tissue can lead to overestimation of muscle mass, hindering the identification of sarcopenic obesity.9 Similarly, in older adults with edema, such as those with heart failure, fluid retention may reduce the reliability of this measure.8 Although the overall sample size was relatively large, it was not sufficient to allow for adequately powered stratified analyses by specific cardiovascular diagnoses. Nevertheless, in hospital emergency settings, particularly in low-resource environments, calf circumference remains a widely accepted and often the only feasible proxy for estimating muscle mass in older populations.9

ConclusionThe prevalence of sarcopenia was 21.3 %, with 42.5 % of older adults classified as at risk by the SARCCalf and 32.5 % by the SARC-F. The SARCCalf exhibited better diagnostic performance than the SARC-F, proving accurate in identifying probable and confirmed sarcopenia. Our findings complement existing research on using the SARCCalf and SARC-F questionnaires to screen for sarcopenia, providing new information specifically on their application in hospital settings for older adults with cardiovascular diseases.

CRediT authorship contribution statementLuciana de Lima Sousa: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Data curation, Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Project administration. Paloma Boni de Lima: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Visualization, Project administration. Thais Ribas Konrad Ribeiro: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Mariana de Grande dos Santos: Investigation. Patrícia Azevedo Garcia: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Resources, Data curation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Visualization, Supervision, Project administration, Funding acquisition.

None to declare.

This study received funding from the Research Support Foundation of the Federal District (FAP-DF), under edict 09/2022. The funding agency played no role in the study design, data collection or analysis, or compiling the manuscript.