Understanding how physical therapists (PTs) approach fall prevention in older adults and factors that may influence their clinical practices is essential for designing knowledge translation strategies.

ObjectivesTo describe PTs’ clinical practices and barriers to implementing fall prevention best practices in older adults and to identify professional characteristics associated with implementation of fall prevention best practices.

MethodsA cross-sectional online survey was conducted. Registered PTs providing care to older adults were recruited through social media platforms. A pre-tested questionnaire assessed clinical practice patterns, sociodemographic and professional characteristics, and behavioral factors influencing the implementation of fall prevention best practices. Data were analyzed descriptively, and multinomial regression identified associations between PTs’ characteristics and practice frequency. The Theoretical Domains Framework and the Capability, Opportunity, Motivation-Behaviour model guided questionnaire design and interpretation of findings.

ResultsAmong 454 PTs surveyed, over 65 % reported frequently (often or always) asking patients about falls, identifying and documenting fall risk factors, and implementing fall prevention interventions. Recommended practices such as balance and strength training were commonly implemented. Barriers to fall prevention best practices included patient denial of risk, reluctance to report falls, and adherence challenges. PTs not practicing in geriatrics or those lacking up-to-date fall prevention knowledge were less likely to report consistent use of best practices.

ConclusionBrazilian PTs frequently integrate fall prevention into older adult care but face patient-related barriers. Addressing the identified barriers through behavior change strategies could enhance the implementation of fall prevention best practices.

Falls occur in 30 % of adults aged 65 years or over annually, representing a significant public health concern, contributing to morbidity, mortality, and reduced quality of life.1 Currently, strong evidence supports the effectiveness of fall prevention strategies.2 Early identification of fall risk factors is an essential step for providing adequate care,3 and a variety of assessment tools that evaluate single or multiple risk factors are available.4–6 Based on a thorough assessment, healthcare professionals may design preventive strategies as a single or multifactorial intervention.2,7 Among preventive interventions, physical exercise is the most commonly studied.2,8 Exercise programs, primarily including balance training and functional exercises, reduce the rate of falls by 24 %.9

Despite the growth of scientific evidence on fall prevention strategies,9 a gap in the evidence-to-practice translation exists. Barriers to implementing fall prevention best practices into routine clinical practice may be at the individual, organization, or policy level.10–12 On the individual level, barriers include healthcare professionals not perceiving falls as a clinical priority, lack of confidence and limited time to perform fall risk screening during routine consultations, and skepticism about fall prevention initiatives, particularly exercise interventions.12 However, the experiences and perceptions of key healthcare professionals involved in fall prevention practices, including physical therapists (PTs), podiatrists, and occupational therapists remain understudied.12

The involvement of PTs in fall prevention is essential, as PTs have the expertise to identify risk factors and implement interventions that enhance mobility and balance in older adults.13 Previous studies with small sample sizes have reported knowledge, frequency of practice, and common interventions implemented by PTs to prevent falls.14,15 These studies mainly focused on PTs’ knowledge about risk factors, or PTs’ knowledge and use of the STEADI (Stopping Elderly Accidents, Deaths & Injuries) developed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.16 According to knowledge translation frameworks,17–21 knowledge is only one domain influencing the adoption of evidence-based practices. Furthermore, implementation science researchers recognize that the lack of a theory-based approach to interpreting barriers and enablers limits the design of context-specific knowledge translation strategies.22 To optimize fall prevention best practices, a comprehensive understanding of PTs' clinical practices and the factors influencing their implementation, is essential. While existing research has provided valuable insights into fall prevention best practices, a comprehensive examination of how PTs address fall prevention in clinical settings remains limited. Understanding the factors and barriers influencing PTs' practice patterns on fall prevention is crucial for designing targeted interventions that align with their needs, challenges, and goals, and promote successful behavior change. Thus, we aimed to describe PTs’ clinical practices and barriers to implementing fall prevention best practices in older adults, and identify professional characteristics associated with implementation of fall prevention best practices.

MethodsStudy designWe conducted a cross-sectional online survey through SurveyMonkey®. The study received ethical approval from the Universidade Cidade de São Paulo (number: 4.931.994). We used the Checklist for Reporting Results of Internet E-Surveys (CHERRIES)23 and the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational studies in Epidemiology (STROBE)24 for designing and reporting the study.

ParticipantsWe targeted Brazilian PTs registered with the Regional Council of Physical Therapy and Occupational Therapy, practicing in any area of physical therapy, and providing care to adults aged 60 or older in any practice setting.

RecruitmentWe used a convenience and snowball sampling.25 Advertising material was created and disseminated through social media (i.e., Facebook, LinkedIn, Instagram, Twitter) between August 2021 and May 2022. To reduce selection bias, we advertised that PTs from all practice areas were eligible.26 We also promoted the study through physical therapy organizations and special interest groups. The survey was accessible via hyperlink, with consent given by selecting an on-screen button. No incentives were offered.

Data collectionDevelopment and testing of the questionnaireWe developed the survey questionnaire using prior questionnaires14,15,27 and a review on health practitioners’ fall prevention perceptions.12 The Theoretical Domains Framework (TDF)21 guided the section on practice behaviour. Through an iterative process, we drafted and refined the questionnaire to cover all 14 TDF domains, focus on best practices (e.g., identifying fall risk factors, providing interventions or recommendations to address these factors, and referral), reduce respondent burden, improve clarity, and align wording with study objectives.

We evaluated content and face validity with a panel of seven experts in fall prevention and survey design.28 After three consultation rounds, we revised the questionnaire wording and response options. We then pre-tested, experience, settings, and regions, assessing comprehensiveness, clarity, and face validity.28 Based on their feedback, we reduced and reordered questions to improve respondent experience. Lastly, we pilot-tested the questionnaire with nine PTs from diverse specialties, experience levels, settings, and regions to assess flow, acceptability, administrative ease, and completion time. Only minor adjustments were made. The final questionnaire (Supplementary material) included three sections:

Section 1: clinical practice informationSection 1 asked PTs about assessing fall history, identifying and recording risk factors, implementing interventions, and making referrals. It also covered the average number of older patients seen weekly, session length, risk factors assessed, tools used, interventions applied, and knowledge of fall prevention guidelines. Responses included 5-point Likert scales and a mix of open- and close-ended formats. To explore barriers to best practices, we included an open-ended question and a close-ended list of barriers from prior studies.10,29 PTs also ranked nine information sources (e.g., databases, colleagues, courses) by usage (1 = most used, 9 = least used).

Section 2: sociodemographic, education, and professional informationSection 2 collected data on age, gender, race/skin color according to the Brazilian classification,30years of practice, highest qualification, physical therapy area, and practice setting (e.g., hospital, home care, outpatient).

Section 3: influences on behavior (awareness, assessment of risk, and implementation of evidence-based interventions)Using a 5-point scale, PTs rated their agreement with 37 statements across TDF domains (e.g., knowledge, skills, beliefs, goals, context, social influences).31 The questionnaire included 66 questions across seven screens, and participants could select “not applicable” or “other” responses.

Before Section 3, participants were asked if they wanted to continue and were shown the estimated time, addressing concerns about length. Due to internet issues reported in testing, multiple entries from the same IP were allowed, but only the last response (based on IP, birthdate, and city) was analyzed. The completion rate is reported as the ratio of participants who completed section 2 by the number of participants completing the first screen.

Sample sizeIt is estimated that approximately 206,170 PTs are registered in Brazil.32 The proportion of PTs working with older adults is unknown, making it to define an optimum sample size. Thus, we used convenience sampling and set a target sample size based on the estimated population of 206,170 PTs. Assuming an expected proportion of 0.50 and a total confidence interval (CI) width of 0.10 at the 95 % confidence level, we estimated a minimum sample size of 384 PTs. This target size is consistent with previous virtual surveys of Brazilian PTs.33–36

Statistical methodsWe exported data from SurveyMonkey to screen for missing data and duplicate entries from the same IP address, which were excluded. Continuous data were tested for normality and summarized using median and 25th and 75th percentiles (P25, P75). Categorical data were summarized using frequencies and percentages.

To identify professional characteristics associated with the frequency of implementing fall prevention best practices, we conducted a backward stepwise multinomial logistic regression. The dependent variable, i.e., frequency of a specific fall prevention practice, was categorized into three groups: "never/rarely/sometimes," "often," and "always." We combined the "never," "rarely," and "sometimes" categories to address low cell counts. "Always" served as the reference category, reflecting consistent adherence to best practices.

The independent variables, selected based on theoretical relevance and prior literature, included years of practice (≤5 years vs ≥6 years [reference]),16 physical therapy qualification (bachelor’s/specialist vs postgraduate [reference]),16 time spent per patient (<45 min, 45–60 min vs >1 hour [reference]),16 area of clinical practice (e.g., not practicing in geriatrics, orthopedics, neurology, or intensive care vs practicing in these areas [reference]), awareness and use of clinical practice guidelines (unaware, aware vs using [reference]), and perceived currency with research evidence (up to date [reference] vs not up to date). All statistical analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics version 23. Results are presented as odds ratios (ORs) with 95 % confidence intervals (CIs) and Nagelkerke pseudo R² values to indicate model fit.

In our study, ORs indicate how likely PTs are (i.e., odds) to report “never/rarely/sometimes” or “often” relative to the reference category “always” (dependent variable), based on their professional characteristics (i.e., each level of the independent variables compared to the reference group) described earlier. An OR >1 indicates higher odds of reporting a frequency of behavior in the comparison category (e.g., “never/rarely/sometimes” or “often”) relative to “always,” meaning the behavior is more likely than in the reference group. An OR <1 indicates lower odds of reporting a frequency of behavior in the comparison category relative to “always,” meaning the behavior is less likely compared to the reference group. Lastly, we used the TDF to interpret and map the findings onto the COM-B (Capability, Opportunity, Motivation–Behaviour) model.31

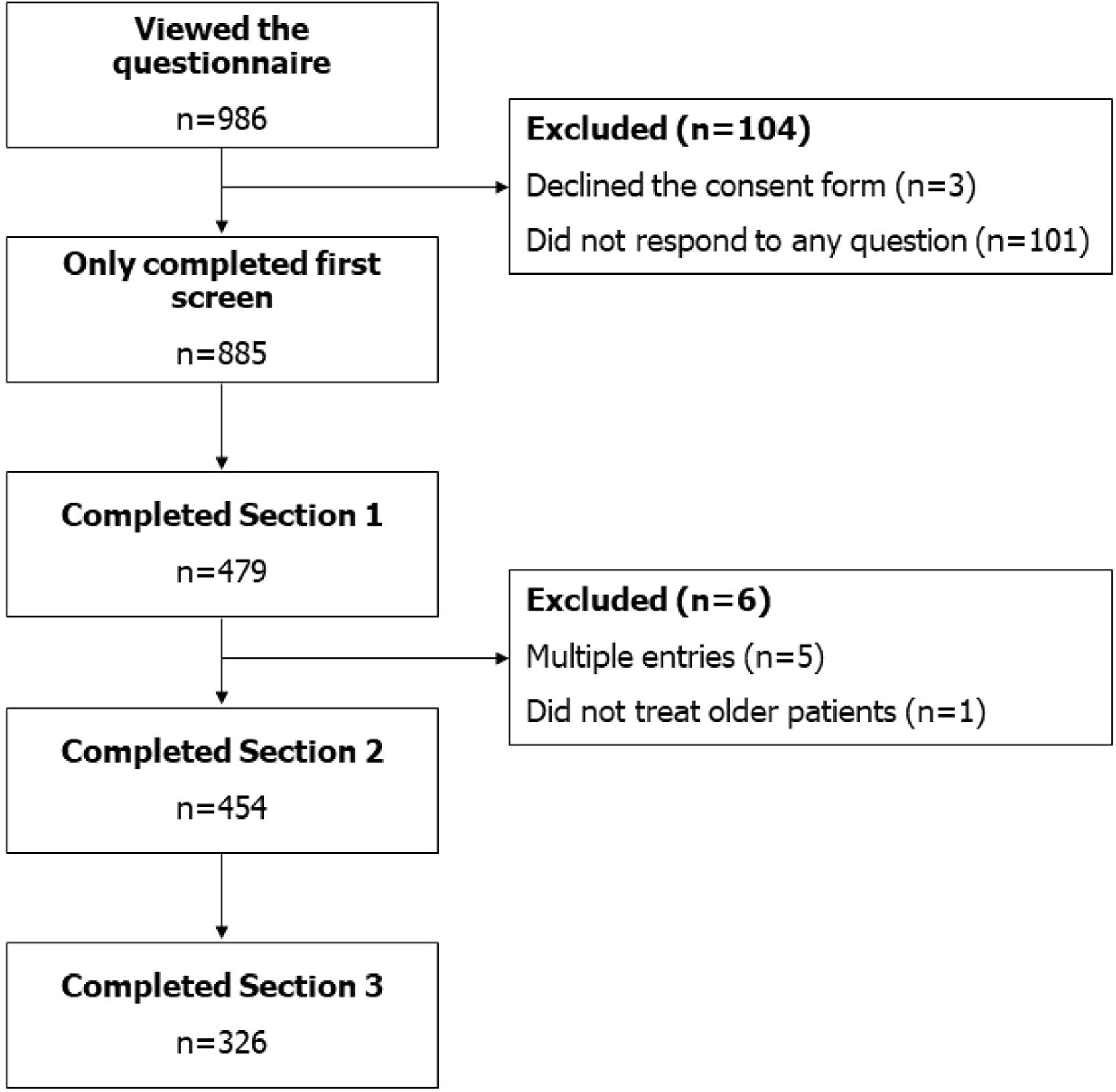

ResultsParticipantsFig. 1 illustrates the flow of participants through the study. Between August 2021 and May 2022, the survey received 986 accesses. We excluded 104 (11 %) entries for declining consent or not answering any question. The recruitment rate was 90 %, and the completion rate was 51 %.

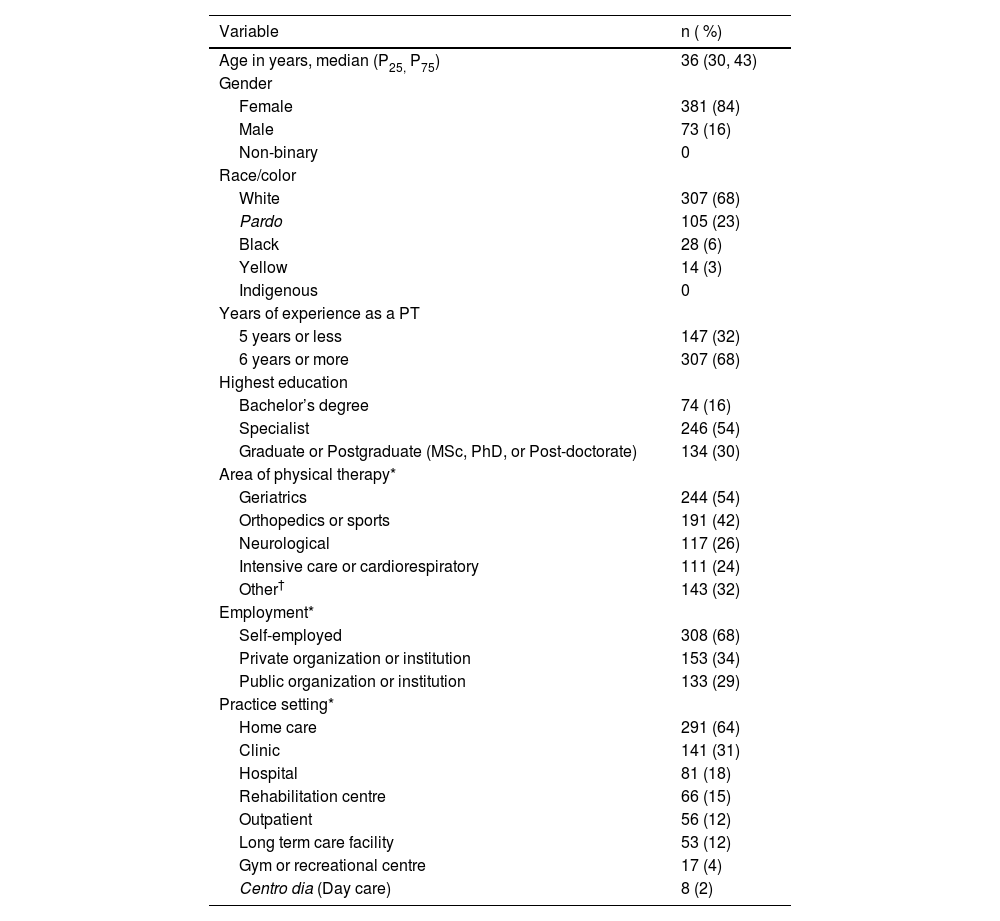

Table 1 provides participant demographics and professional characteristics. Most PTs were female (84 %), median age 36 years (P25–P75: 30–43), and 68 % had ≥6 years of experience. Over half had a specialist degree, 68 % were self-employed, and 64 % worked in home care. PTs reported practicing in over 15 specialties, mainly geriatrics (54 %), followed by orthopedics/sports (42 %).

Demographic and professional characteristics of PTs (n = 454).

| Variable | n ( %) |

|---|---|

| Age in years, median (P25, P75) | 36 (30, 43) |

| Gender | |

| Female | 381 (84) |

| Male | 73 (16) |

| Non-binary | 0 |

| Race/color | |

| White | 307 (68) |

| Pardo | 105 (23) |

| Black | 28 (6) |

| Yellow | 14 (3) |

| Indigenous | 0 |

| Years of experience as a PT | |

| 5 years or less | 147 (32) |

| 6 years or more | 307 (68) |

| Highest education | |

| Bachelor’s degree | 74 (16) |

| Specialist | 246 (54) |

| Graduate or Postgraduate (MSc, PhD, or Post-doctorate) | 134 (30) |

| Area of physical therapy* | |

| Geriatrics | 244 (54) |

| Orthopedics or sports | 191 (42) |

| Neurological | 117 (26) |

| Intensive care or cardiorespiratory | 111 (24) |

| Other† | 143 (32) |

| Employment* | |

| Self-employed | 308 (68) |

| Private organization or institution | 153 (34) |

| Public organization or institution | 133 (29) |

| Practice setting* | |

| Home care | 291 (64) |

| Clinic | 141 (31) |

| Hospital | 81 (18) |

| Rehabilitation centre | 66 (15) |

| Outpatient | 56 (12) |

| Long term care facility | 53 (12) |

| Gym or recreational centre | 17 (4) |

| Centro dia (Day care) | 8 (2) |

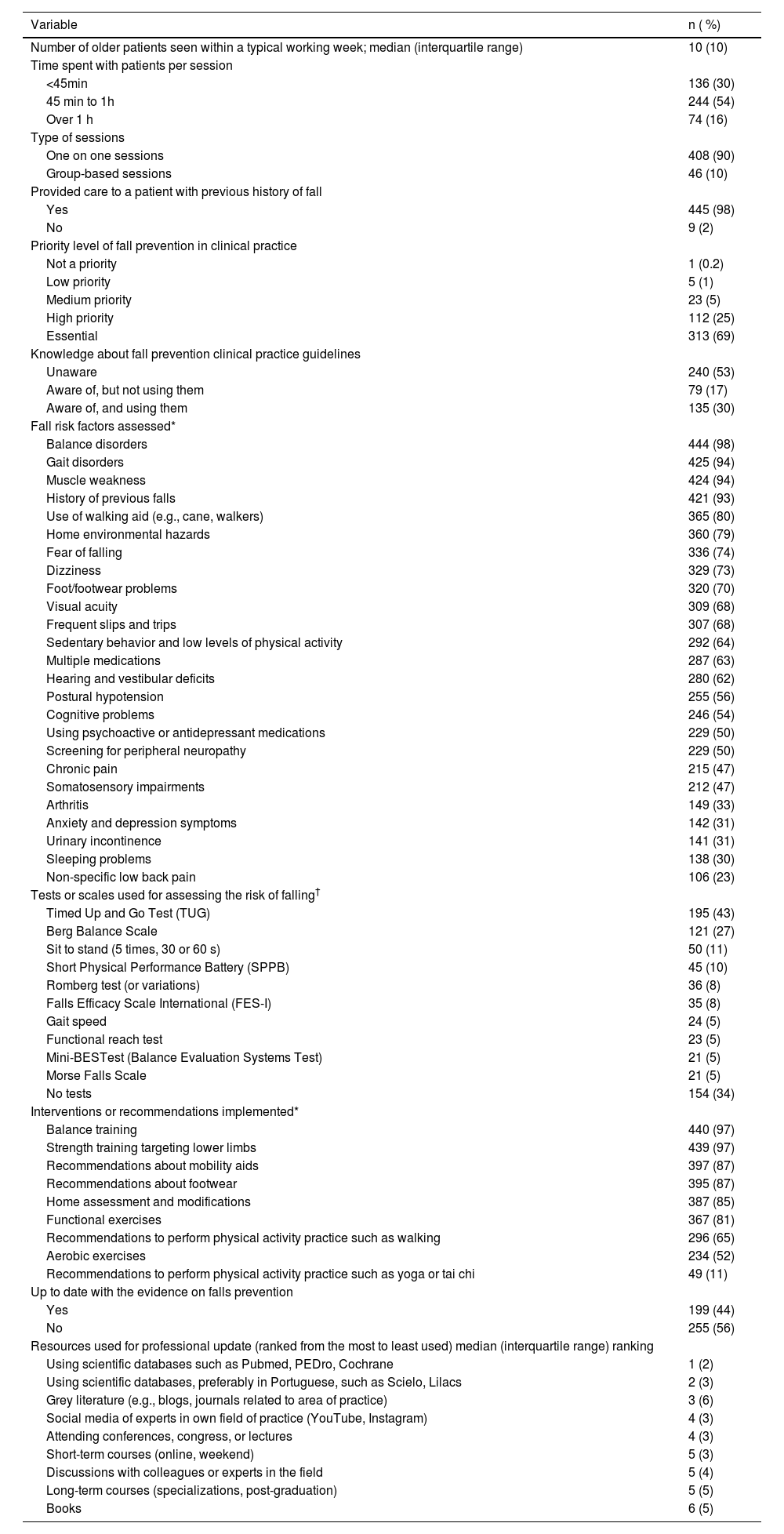

Table 2 details practice patterns. PTs reported caring for an average of 10 older patients per week, with 54 % spending 45–60 min per session. Of 454 PTs, 445 (98 %) had treated a patient with a prior fall, and 313 (69 %) viewed fall prevention as a clinical priority.

Responses to practice pattern (n = 454).

| Variable | n ( %) |

|---|---|

| Number of older patients seen within a typical working week; median (interquartile range) | 10 (10) |

| Time spent with patients per session | |

| <45min | 136 (30) |

| 45 min to 1h | 244 (54) |

| Over 1 h | 74 (16) |

| Type of sessions | |

| One on one sessions | 408 (90) |

| Group-based sessions | 46 (10) |

| Provided care to a patient with previous history of fall | |

| Yes | 445 (98) |

| No | 9 (2) |

| Priority level of fall prevention in clinical practice | |

| Not a priority | 1 (0.2) |

| Low priority | 5 (1) |

| Medium priority | 23 (5) |

| High priority | 112 (25) |

| Essential | 313 (69) |

| Knowledge about fall prevention clinical practice guidelines | |

| Unaware | 240 (53) |

| Aware of, but not using them | 79 (17) |

| Aware of, and using them | 135 (30) |

| Fall risk factors assessed* | |

| Balance disorders | 444 (98) |

| Gait disorders | 425 (94) |

| Muscle weakness | 424 (94) |

| History of previous falls | 421 (93) |

| Use of walking aid (e.g., cane, walkers) | 365 (80) |

| Home environmental hazards | 360 (79) |

| Fear of falling | 336 (74) |

| Dizziness | 329 (73) |

| Foot/footwear problems | 320 (70) |

| Visual acuity | 309 (68) |

| Frequent slips and trips | 307 (68) |

| Sedentary behavior and low levels of physical activity | 292 (64) |

| Multiple medications | 287 (63) |

| Hearing and vestibular deficits | 280 (62) |

| Postural hypotension | 255 (56) |

| Cognitive problems | 246 (54) |

| Using psychoactive or antidepressant medications | 229 (50) |

| Screening for peripheral neuropathy | 229 (50) |

| Chronic pain | 215 (47) |

| Somatosensory impairments | 212 (47) |

| Arthritis | 149 (33) |

| Anxiety and depression symptoms | 142 (31) |

| Urinary incontinence | 141 (31) |

| Sleeping problems | 138 (30) |

| Non-specific low back pain | 106 (23) |

| Tests or scales used for assessing the risk of falling† | |

| Timed Up and Go Test (TUG) | 195 (43) |

| Berg Balance Scale | 121 (27) |

| Sit to stand (5 times, 30 or 60 s) | 50 (11) |

| Short Physical Performance Battery (SPPB) | 45 (10) |

| Romberg test (or variations) | 36 (8) |

| Falls Efficacy Scale International (FES-I) | 35 (8) |

| Gait speed | 24 (5) |

| Functional reach test | 23 (5) |

| Mini-BESTest (Balance Evaluation Systems Test) | 21 (5) |

| Morse Falls Scale | 21 (5) |

| No tests | 154 (34) |

| Interventions or recommendations implemented* | |

| Balance training | 440 (97) |

| Strength training targeting lower limbs | 439 (97) |

| Recommendations about mobility aids | 397 (87) |

| Recommendations about footwear | 395 (87) |

| Home assessment and modifications | 387 (85) |

| Functional exercises | 367 (81) |

| Recommendations to perform physical activity practice such as walking | 296 (65) |

| Aerobic exercises | 234 (52) |

| Recommendations to perform physical activity practice such as yoga or tai chi | 49 (11) |

| Up to date with the evidence on falls prevention | |

| Yes | 199 (44) |

| No | 255 (56) |

| Resources used for professional update (ranked from the most to least used) median (interquartile range) ranking | |

| Using scientific databases such as Pubmed, PEDro, Cochrane | 1 (2) |

| Using scientific databases, preferably in Portuguese, such as Scielo, Lilacs | 2 (3) |

| Grey literature (e.g., blogs, journals related to area of practice) | 3 (6) |

| Social media of experts in own field of practice (YouTube, Instagram) | 4 (3) |

| Attending conferences, congress, or lectures | 4 (3) |

| Short-term courses (online, weekend) | 5 (3) |

| Discussions with colleagues or experts in the field | 5 (4) |

| Long-term courses (specializations, post-graduation) | 5 (5) |

| Books | 6 (5) |

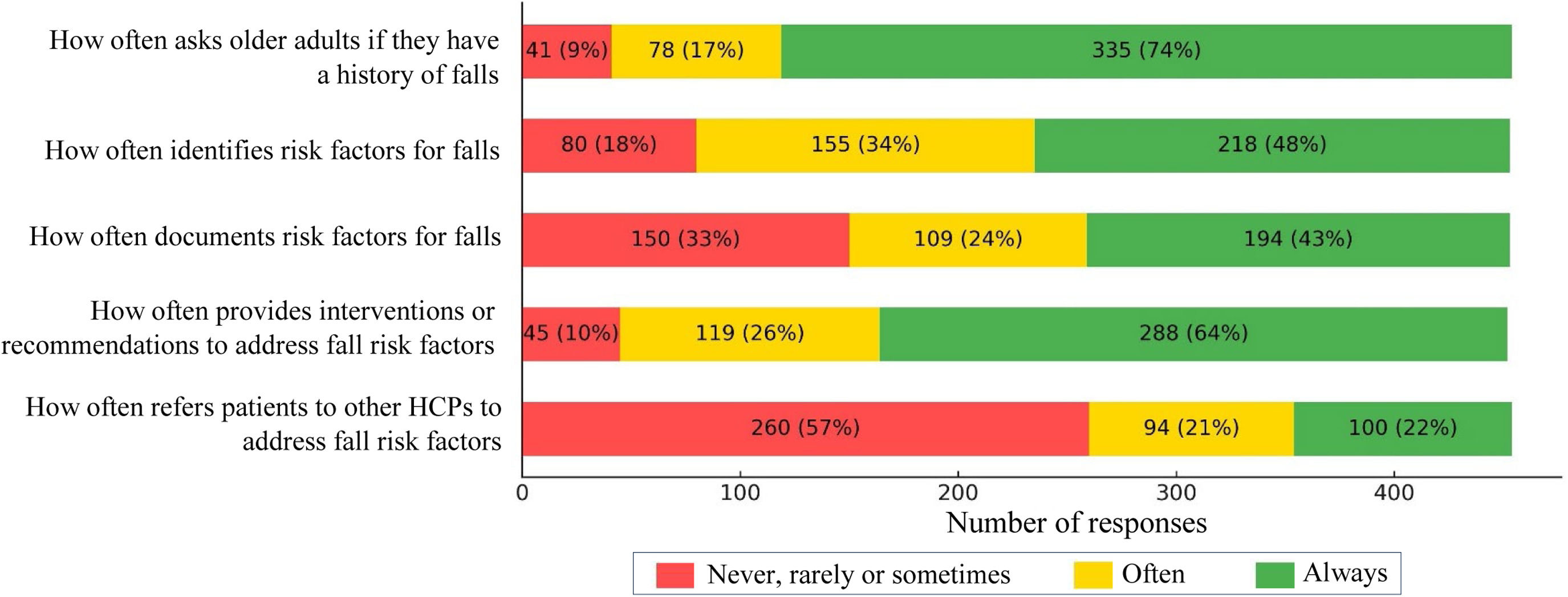

Fig. 2 shows the frequencies of best practice implementation. Over 73 % of PTs reported always asking about fall history; 48 % and 43 % reported identifying and documenting risk factors, respectively. About 63 % reported always providing interventions or recommendations. Referrals to other healthcare professionals were less common, with 57 % reporting never, rarely, or sometimes making referrals.

Common assessment tools included the Timed Up and Go Test (43 %), Berg Balance Scale (27 %), and Sit-to-Stand (11 %), though 34 % did not mention using any test. The main risk factors identified were balance issues (98 %), gait disorders (94 %), and muscle weakness (93 %). Common interventions were balance training (97 %), lower limb strengthening (97 %), and mobility aid recommendations (87 %) (Table 2).

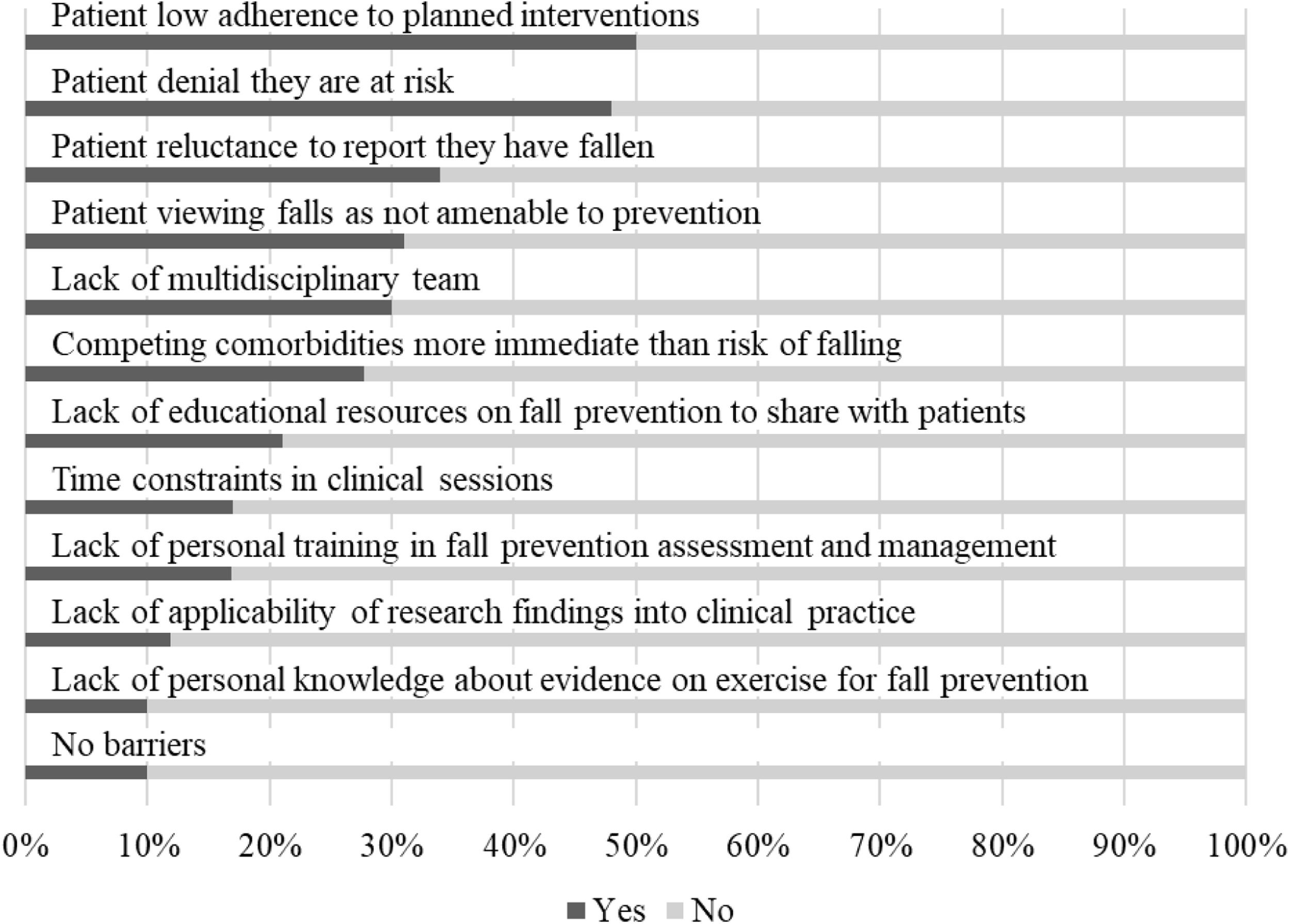

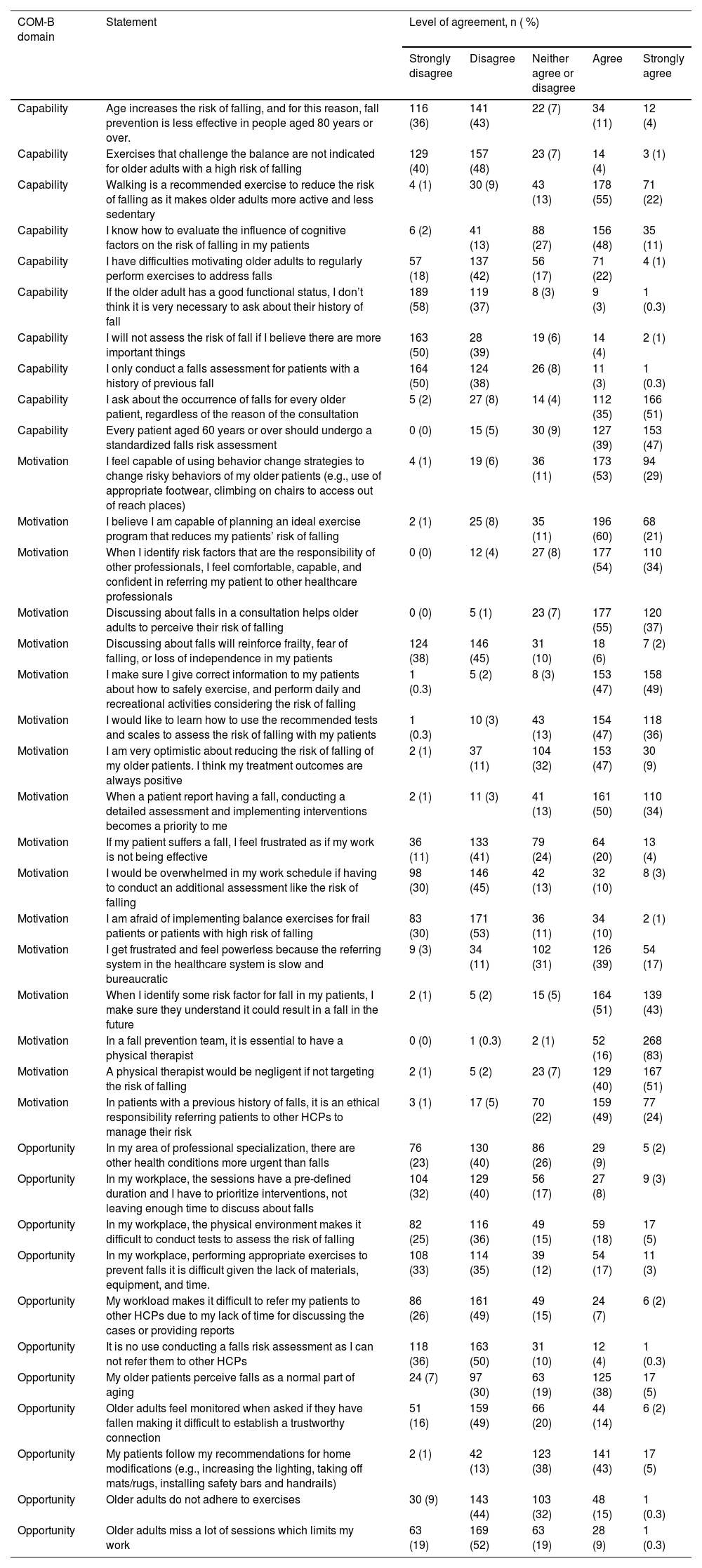

Fig. 3 and Appendix 1 summarize barriers and behavioral influences mapped to the COM-B model.

Capability domain (Knowledge, skills, behavior regulation, memory attention and decision processes)Over half of PTs (53 %) were unaware of clinical practice guidelines for falls prevention, and 56 % did not consider themselves up to date with the evidence on falls prevention. Of the resources used to keep up to date, PTs reported using primarily scientific databases such as Pubmed, PEDro, and Cochrane.

Opportunity domain (Social influences, environment context and resources)PTs identified key barriers to implementing best practices, primarily patient-related: low adherence to interventions (50 %), denial of fall risk (48 %), reluctance to report falls (34 %), and perceiving falls as unavoidable (31 %) (Fig 3). Nearly 72 % of PTs do not view time constraints as a barrier to discussing fall prevention. Similarly, over 61 % and 68 % disagreed that environmental limitations (e.g., lack of space) or insufficient equipment affect their ability to deliver fall-prevention exercises. About 76 % also disagreed that their workload limits referrals to other healthcare professionals (Appendix 1). Approximately 86 % of PTs disagreed that older adults view falls as a normal part of aging. Over 64 % disagreed that asking about falls undermines trust, 53 % disagreed that older adults have poor adherence to exercise, and 71 % disagreed that missed sessions frequently disrupt treatment plans.

Motivation domain (Social/professional role and identity, beliefs about consequences, beliefs about capability, optimism, intentions, reinforcement, goals; emotions)PTs generally agreed on the importance of assessing fall risk and using balance training, regardless of age, function, or risk level. They strongly disagreed that it’s unnecessary to ask high-functioning older adults about falls or to assess only those with a fall history. About 83 % agreed that all patients ≥60 years should be screened, and 88 % rejected the idea that balance exercises are unsuitable for high-risk older adults. Most (53 %) disagreed that fall prevention is less effective in adults ≥80, and 60 % disagreed that they struggle to motivate older adults to exercise (Appendix 1).

PTs generally expressed confidence in their fall management skills, optimism about intervention outcomes, and a strong belief in the PT’s role on fall prevention teams. Most (92 %) agreed that discussing falls increases patients’ risk awareness, while 83 % disagreed it fosters frailty, fear, or loss of independence. About 75 % disagreed that assessing fall risk is overwhelming. Over 81 % felt capable of using behavior change strategies, and 78 % were not afraid to implement balance exercises for frail or high-risk patients. Half disagreed that they felt frustrated if a patient experiences a fall despite treatment. Nearly all (99 %) viewed PTs as essential on fall prevention teams, 90 % believed failing to address fall risk was negligent, 72 % viewed referrals as an ethical duty, and 56 % reported feeling powerless within a slow, bureaucratic referral system.

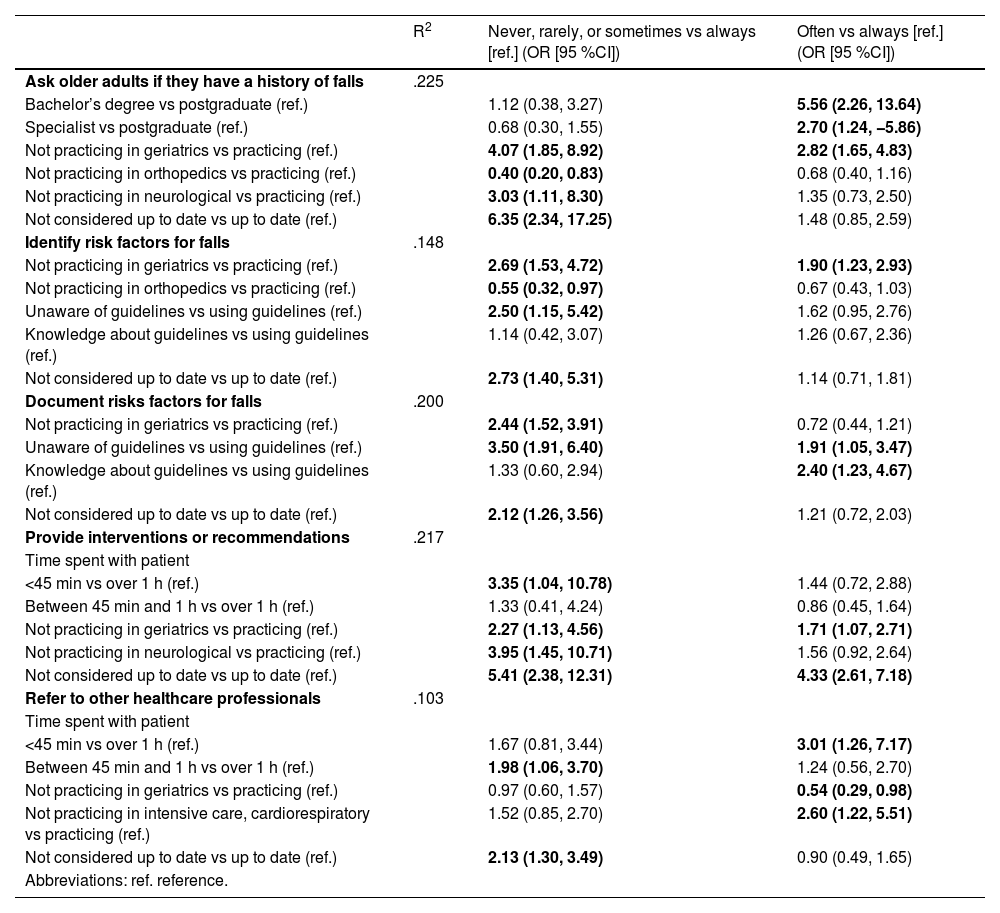

PTs’ professional characteristics associated with the implementation of fall prevention best practicesAppendix 2 presents the results of the multinomial logistic regression examining factors associated with the frequency of implementing fall prevention best practices. Two factors, area of physical therapy practice and self-perceived currency with the literature, consistently distinguished between higher and lower frequencies of fall prevention best practices across all five behaviors. PTs not practicing in geriatrics had higher odds of reporting “never/rarely/sometimes” or “often” relative to “always” when asking about falls (OR: 4.07; 95 % CI: 1.85, 8.92), identifying (OR: 2.69; 95 % CI: 1.53, 4.72), documenting fall risk factors (OR: 2.44; 95 % CI: 1.52, 3.91), and providing interventions or recommendations (OR: 2.27; 95 % CI: 1.13, 4.56). Similarly, PTs who did not perceive themselves as up to date with the literature had higher odds of reporting “never/rarely/sometimes” or “often” relative to “always” when asking about falls (OR: 6.35; 95 % CI: 2.34, 17.25), identifying (OR: 2.73; 95 % CI: 1.40, 5.31), documenting fall risk factors (OR: 2.12; 95 % CI: 1.26, 3.56), providing interventions (OR: 5.41; 95 % CI: 2.38, 12.31), and referring to other healthcare professionals (OR: 2.13; 95 % CI: 1.30, 3.49). Time spent with patients also influenced practices: PTs spending <45 min had higher odds of reporting “never/rarely/sometimes” or “often” relative to “always” in providing interventions (OR: 3.35; 95 % CI: 1.04, 10.78) and referring patients (OR: 1.98; 95 % CI: 1.06, 3.70). Notably, PTs not practicing in orthopedics had lower odds of reporting “never/rarely/sometimes” or “often” relative to “always” when asking about falls (OR: 0.40; 95 % CI: 0.20, 0.83) and identifying fall risk factors (OR: 0.55; 95 % CI: 0.32, 0.97), suggesting that PTs in orthopedics are more likely to report suboptimal fall prevention practices.

DiscussionWe described the clinical practices and barriers to implementing fall prevention best practices among 454 PTs in Brazil and identified professional characteristics influencing their use. Most PTs reported routinely asking patients about prior falls, identifying and documenting risk factors, and implementing targeted interventions. PTs commonly used recommended tools like the Timed Up and Go Test and Berg Balance Scale, along with evidence-supported interventions such as balance and strength training, consistent with prior studies.14,15,37 PTs working in geriatrics with older people were more likely to frequently apply best practices, while those outside geriatrics had higher odds of infrequent implementation across several practices, including asking about falls, identifying risk factors, and providing interventions. PTs who did not feel up to date with fall prevention research were also more likely to report lower engagement in best practices. Additionally, PTs in orthopedics were more likely to report suboptimal practices for screening and identifying fall risk factors. Spending under 45 min with patients was linked to lower implementation of interventions and referrals. These findings highlight the importance of geriatricspecialization in geriatrics and gerontology, ongoing professional development, and sufficient time for effective fall prevention.

Overall, PTs in our study align with best practices in managing patients’ fall risk.38 However, some findings are worth noting. Although anxiety, depression, and urinary incontinence are linked to increased fall risk,39,40 they are not commonly assessed by PTs. Similarly, less than half reported assessing chronic pain. In our prior study,41 older adults identified pain as a key barrier to participating in fall prevention programs. Routinely assessing and managing pain may help PTs address both fall risk and treatment adherence. Over 68 % reported assessing home hazards and visual acuity, though it was unclear how they do so in practice. Lastly, there appears to be a misunderstanding of walking as a fall prevention strategy. About 65 % recommended walking to prevent falls, and over 76 % agreed it helps reduce fall risk by keeping older adults active. However, current evidence raises uncertainty about the effectiveness of walking programs as a standalone intervention for reducing falls.9

Compared with previous studies of PTs in Nigeria14 and in the USA,15 Brazilian PTs more often report asking patients about falls, identifying risk factors, and implementing interventions to address fall risk. However, USA PTs document fall risk factors more frequently than Brazilian PTs. In all three countries, referring patients to other HCPs remains the least performed strategy, with 43 % in Brazil, 20 % in Nigeria, and only 6 % in the USA reporting always or often doing so. In contrast to a previous study,12 PTs in our study did not view time constraints or lack of environmental resources as barriers to managing falls. Interestingly, we found conflicting responses regarding older adults’ behavior and its influence on PT practice. Although PTs cited patient adherence and perceptions about falls as key barriers, they largely disagreed that older patients fail to adhere to exercise or that missed sessions limit their work.

Our findings highlight that the role of PTs requires a wide range of competences and skills. Consistent with a previous qualitative study,42 PTs recognize the need for skills in motivation and behavior change support, alongside their expertise in balance training. PTs also emphasized the importance of being active listeners and communicators, building trust and strong relationships with older patients to achieve success.42 However, a previous systematic review43 showed that PTs often apply only a limited number of behavior change techniques when promoting physical activity. One such technique is health coaching, shown to effectively increase physical activity in older adults.44 Health coaching involves providers (i.e., PTs) applying knowledge and skills (including physical therapy, gerontology, and coaching expertise; interpersonal skills; patient-directed goals; and engagement strategies) to help individuals change lifestyle-related behaviors, mobilizing internal strengths and external resources for sustainable improvements in health and quality of life.45 Although evidence on health coaching effects delivered by PTs is still unclear,46 older adults have reported positive experiences with health coaching for promoting physical activity and preventing falls,47 suggesting it may strengthen the PT–patient relationship and serve as both an engagement and maintenance strategy.47

Strength and limitationsThe main strength of this study lies in the use of recommended online survey procedures and strong theory-based development. To our knowledge, this is the first rigorous, theory-informed survey investigating clinical practices and factors influencing the implementation of fall prevention best practices by PTs in Brazil. Additionally, our study achieved a relatively large sample compared to similar previous research. However, some limitations should be noted. As with virtual survey-based studies using convenience sampling, there is a risk of selection and response biases, potentially overrepresenting PTs more engaged or interested in fall prevention. Although we aimed to mitigate this by recruiting from various professional backgrounds, our sample was primarily composed of PTs working in geriatrics and home care settings. Therefore, the findings may reflect the practices of this specialist subpopulation and may not fully generalize to the broader population of PTs working with older adults in other settings.

ConclusionsOverall, PTs in Brazil report practices aligned with fall prevention best practices in older adults. PTs who do not practice in geriatrics or who do not perceive themselves as up to date with the evidence were less likely to consistently ask about falls, identify and document risk factors, or implement interventions. Barriers to implementation were often related to older adults' reluctance to report falls or adhere to interventions. Using the TDF, our study lays a foundation for addressing evidence-to-practice gaps among PTs. To strengthen fall prevention strategies, future efforts should focus on improving access to continuing education, integrating behavioral strategies like health coaching, and developing system-level supports to enhance adherence to evidence-based care. Future research should assess whether these strategies effectively help PTs implement fall prevention practices more consistently across settings.

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.