The Glittre Activities of Daily Living (Glittre-ADL) test without backpack was recently validated to assess the functional capacity of people with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)

ObjectiveTo understand the perceptions of people with COPD about the Glittre-ADL test with and without backpack and the possible similarities with their activities of daily living (ADLs).

MethodsParticipants performed 2 Glittre-ADL tests with a backpack (visit 1). On visit 2, participants randomly performed the Glittre-ADL test with and without backpack and completed a semi-structured interview with questions about the tests. Interviews were analyzed according to thematic analysis.

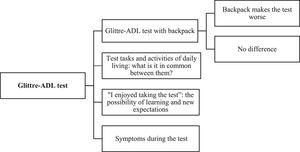

ResultsTwelve participants aged between 57 and 76 years with mild to severe COPD were included. Interviews were grouped into four thematic categories: (1) Glittre-ADL test with a backpack: does the backpack make the test worse, or does it not matter?; (2) test tasks and ADL: what is in common between them?; (3) “I enjoyed taking the test”: the possibility of learning and new expectations; and (4) symptoms during the Glittre-ADL tests.

ConclusionThe following perceptions while performing the Glittre-ADL test with and without the backpack were observed: dyspnea and fatigue sensation, difficulty using the backpack while performing tasks such as squatting, and similarities to ADLs tasks despite different perspectives regarding the degree of ease and expectations on how to perform test tasks at home.

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is the fourth major cause of death worldwide1 and one of the leading causes of functional capacity decline2 [i.e., decreased potential to perform activities of daily living (ADLs)].3 People with COPD usually adopt a sedentary lifestyle that may lead to muscle deconditioning. The association of muscle deconditioning with dyspnea, a common symptom in people with COPD, may increase fatigue in performing ADLs and cause inactivity and reduced functional capacity.4 Therefore, assessing the functional capacity of people with COPD is fundamental because it may indicate the degree of activity limitation or predict exacerbations5 and hospitalizations.6

Functional capacity is usually assessed by field tests or questionnaires.3 The Glittre Activities of Daily Living (Glittre-ADL) test was developed and validated to assess the functional capacity of individuals with COPD.7 The test includes lower and upper limb activities, such as sitting, standing, walking, climbing stairs, and moving objects from shelves of different heights.7 The primary outcome of the Glittre-ADL test is the time spent to complete 5 laps on a 10-meter flat track. The study that established the Glittre-ADL test proposed using a backpack weighing 2.5 kg for females and 5 kg for males.8 The weight of 2.5 kg simulates a supplementary oxygen unit, and the differences between the weight of the backpacks normalize muscle mass discrepancies between sexes.8

Recently, a study by Mendes et al.9 validated the Glittre-ADL test without a backpack. Although the test without backpack was highly correlated with the Glittre-ADL test with backpack, with both eliciting similar physiological responses in people with COPD,9 the patient's perceptions when performing the tests with and without backpack have not been investigated. Understanding the perceptions of people wearing a backpack during the test may contribute to implementing assessment tools that meet needs and expectations. Therefore, this study aimed to comprehend the perception of people with COPD regarding the Glittre-ADL test performed with and without backpack and the applicability of the test to their ADLs.

MethodsThis qualitative study integrates a research project related to the Glittre-ADL test performed at the Laboratory of Assessment and Research in Cardiorespiratory Performance of the Escola de Educação Física, Fisioterapia e Terapia Ocupacional (UFMG) and in an outpatient center of pulmonary rehabilitation located in the metropolitan region of the city. The study was approved by the research ethics committee of the UFMG (no. 2.510.453 CAAE: 82096618.2.0000.5149) and conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki. All participants provided written informed consent.

ParticipantsThis study involved people who participated in the research project related to the Glittre-ADL test. Those diagnosed with COPD (I to IV stage)10 and clinically stable over the past month were included. Exclusion criteria included people with neuromuscular, orthopedic, or neurological conditions limiting exercise performance; major lung disease; body mass index above 35 kg/m²; worsening of symptoms during test days; and inability to understand or perform the study procedures. People who performed exhaustive physical activity in the 48 h prior to the tests were invited to return another day. Of the 28 potential individuals for the research project, 12 participated in this study. The number of participants for this study was defined during interviews according to saturation criteria.11

Data collectionParticipants performed two Glittre-ADL tests with a backpack (visit 1). On visit 2, participants randomly performed the Glittre-ADL test with and without backpack and completed an interview with questions about the tests. Data were collected using a semi-structured interview and a script formulated by the authors; one researcher (author 1) conducted a pilot study with two participants to verify the adequacy of questions. The adjustments performed after this pilot study resulted in a final version of the interview with two open questions. The first question, asked after the tests were completed, addressed the thoughts and perceptions of participants about the Glittre-ADL test with and without backpack. The second question queried how the participants felt after the test and about similarities between the Glittre-ADL and their typical ADLs. One author individually conducted, recorded, and fully transcribed all interviews to ensure data uniformity. Participants confirmed the content of transcripts.12

Data analysisData were analyzed according to the thematic analysis proposed by Braun and Clarke13: (a) familiarization with the data by complete reading and re-reading the material, (b) generating and comparing codes, (c) generating themes, (d) reviewing themes according to objectives of the study, (e) defining and naming themes, and (f) writing and contextualizing the analysis with the literature.

ReflexivityThree authors of this study are physical therapists, and one is an occupational therapist. The second author is a researcher with experience conducting and publishing qualitative research. All authors reviewed and participated in formulating questions for the interview script and participants had no prior relationship with any author, as reinforced by Rose and Jhonson.14 During data analysis, two researchers (authors 1 and 2) discussed and named themes in 3 in-person meetings. After extensive data analysis and final definition of themes, the authors concluded that the study objective was achieved (i.e., no need for more data collection).

ResultsTwelve participants (eight males and four females, aged between 57 and 76) were included in the study. Two participants were classified as GOLD I, four as GOLD II, five as GOLD III, and two as GOLD IV. Table 1 presents the clinical and sociodemographic data of the participants.

Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of participants (n = 12).

GOLD: Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease.

Three participants were employed, and four were retired. All participants lived in their own houses, nine with a family member and three alone. Fig. 1 presents a summary of the thematic categories that emerged from the perceptions of the individuals.

Glittre-ADL test with backpack: does the backpack make the test worse, or does it not matter?Participants reported facing difficulties using the backpack during the Glittre-ADL test. These difficulties were observed in tasks such as squatting, which occurs in the test circuit when moving the weights from the middle shelf to the floor. They also indicated fatigue in the legs and for breathing.

“Performing the test with a backpack was difficult. The test was as hard as carrying heavy shopping bags home” (N3, 67 years old, female, GOLD 4).

"With a backpack, the test becomes heavier during a squat because it overloads legs, especially on the last shelf. I felt I ‘pushed’ my spine more while squatting with a backpack than without one. The test was fine without backpack; although I still had difficulty performing squats, there was no weight” (N11, 63 years old, male, GOLD 2).

“The test was heavier with a backpack. It was more tiring for lungs and legs.” (N6, 76 years old, male, GOLD 3).

The following participant reported more comfort without the backpack, although the presence of fatigue:

"Without a backpack, the test was more comfortable; but I was tired too, mainly breathing, I got really tired.” (N10, 76 years old, male, GOLD 3)

The following participants reported not observing differences between testing with or without the backpack:

“I did not see a difference between performing the test with and without a backpack. I thought that without a backpack would be easier, but it was not. I thought I would have more difficulty with a backpack, but my performance was reasonable. From zero to ten, I would give myself a score of five.” (N9, 68 years old, male, GOLD 3).

“(...) the tests with and without backpack were the same” (N4, 69 years old, male, GOLD 4).

“I did not think that tests were different; I think that tests with and without backpack are the same thing.” (N5, 60 years old, female, GOLD 2).

Test tasks and ADLs: what is in common between them?Participants reported similarities between tasks in the Glittre-ADL test circuit and ADLs, whether at home or work. They highlighted differences in the degree of ease of tasks and the fatigue resulting from the performance rhythm.

“They are similar. The only difference is the weight. However, even at home, we also carry weight, such as full buckets or drag furniture. Without a backpack, I considered tasks normal activities, like things we usually do at home or even in some jobs. For example, I used to do similar activities when I was a physical education teacher.” (N8, 58 years old, female, GOLD 1).

“Placing objects on the shelf is very similar to my routine of grabbing building materials and building floors. I am used to climbing stairs during the whole day, so I found tasks very similar” (N12, 63 years old, male, GOLD 3).

“I think test tasks are easier than activities I usually do at home because I work with many other activities” (N5, 60 years, female, GOLD 2).

“I think test tasks were more tiring than my activities of daily living because, at home, I can stop whenever I want to until I decide to return to my activities” (N3, 67 years old, female, GOLD 4).

“I enjoyed taking the test": the possibility of learning and new expectations

Participants reported enjoying the test and indicated that it enabled learning and generated expectations on performing the proposed circuit tasks at home. They also revealed feeling good and energetic after completing the tests.

“I enjoyed performing tests because it is an expectation of what I can do as an exercise afterward.” (N1, 67 years old, male, GOLD 2).

“I wished to do my best to cross my limits and demonstrate improvement.” (N9, 68 years old, male, GOLD 3).

“I liked to perform the test to improve my breathing. I was having good thoughts, and I was focused on accomplishing the test.” (N3, 67 years old, female, GOLD 4)

“I felt even more energized to perform chores.” (N2, 57 years old, female, GOLD 2).

“Performing the tests brought a lot of learning to me. If needed, I would perform the test by myself to test my endurance.” (N8, 58 years old, female, GOLD 1).

Symptoms during the Glittre-ADL testsParticipants perceived dyspnea and fatigue as the main symptoms during tests:

“I felt really tired. I felt my body and my breathing very tired. The difference is that body recovers faster than breathing.” (N10, 76 years old, male, GOLD 3).

“I felt breathless during tests, which limited myself a little and left me breathless, with a feeling that my lungs were not expanding well in some tasks” (N12, 63 years old, male, GOLD 3).

“I felt more tired, especially while moving objects down and up” (N3, 67 years old, female, GOLD 4).

DiscussionParticipants reported difficulties while performing the Glittre-ADL test with backpack. Both Glittre-ADL tests resembled ADLs for the participants, who also reported feeling more motivated to exercise after completing the tests. Dyspnea and fatigue were the main symptoms experienced during Glittre-ADL tests.

Participants from both sexes reported difficulties during the Glittre-ADL test performed with a backpack, which may be explained by the additional load imposed by the backpack. The tasks may compromise blood flow to postural and gait-related muscles when reaching high respiratory demand,15 resulting in fatigue. Wearing a weighted backpack may induce gait instability; consequently, individuals may walk slower.16 Also, the load carried in the backpack during walking increases muscle activity due to additional muscle effort, generating greater energy expenditure.17

In the present study, participants with different degrees of airflow obstruction reported similarities between the tests with and without backpack. A previous quantitative study demonstrated that disease severity measured using forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1) was weakly associated with low levels of ADLs.18 This indicates that the level of ADLs of people with COPD should be assessed using a specific functional test for the activity domain of the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health rather than a test that assesses only one component of the structure, such as FEV1. COPD is a multisystemic disease, and each component may account for different dimensions of activity limitation.2

Because tests were randomized, some participants performed the Glittre-ADL test without a backpack before the test with a backpack. People with COPD usually do not push themselves to maximal capacity when performing a test for the first time due to fear of dyspnea and fatigue.19 Once they get used to one test, they feel more confident performing the next test faster.19 Therefore, when the Glittre-ADL test with a backpack was performed later in the second visit, the backpack might not have been perceived as a relevant factor. Perceptions of their health conditions vary among individuals with advanced lung disease.20 Similarly, in our study, perceptions of Glittre-ADL tests also differed among participants; however, no one reported that the test with a backpack was easier.

Reports revealed that test tasks were similar to those performed during ADLs regardless of disease severity or employment condition. The participants who performed professional activities identified the test with and without backpack as similar to tasks usually performed in their jobs; those retired also identified similarities between the tasks of the tests and their ADLs. One participant perceived test tasks as more fatiguing than ADLs because the home environment allows interrupting a task and rest whenever feeling tired. Taking periods of rest is a common strategy adopted by people with COPD because ventilatory limitation is one of the main dyspnea mechanisms that causes cessation of activities during ADLs.19 The Glittre-ADL test was developed to resemble real-life situations and improve the functional capacity assessment of people with COPD.7,21 Tasks that compose the test were chosen based on the Modified Pulmonary Functional Status and Dyspnea Questionnaire, developed to assess the influence of fatigue and dyspnea on daily activities and compare changes in daily activities before and after COPD diagnosis.22 For example, climbing stairs was related to different daily life situations, such as climbing stairs on a bus or workplace.

The present study showed that Glittre-ADL tests motivated participants to be more active in daily activities. Performing the Glittre-ADL test may help interrupt the cycle of physical inactivity and sedentary lifestyle, usually observed in people with COPD.4 Participants also attributed the Glittre-ADL test performance to aspects they judged important for maintaining and improving health conditions. The concern about maintaining personal integrity made participants adopt motivational strategies for improving test performance.23 This is another reason for considering the Glittre-ADL test without a backpack to assess functional capacity. Assessing whether participants can perform ADLs indicates autonomy and makes them feel confident.

Participants reported increased dyspnea and fatigue during both tests. People with COPD usually complain of exertional dyspnea during ADLs, which reduces functional capacity and ability to carry out daily routines (e.g., self-care and household chores).24 This was demonstrated in the present study when N12 described that shortness of breath during test tasks simulated those experienced during daily routines. The combination of dyspnea and leg discomfort also limits exercise performance in many individuals.25 In the present study, such symptoms were reported when N10 reported dyspnea, the former being the most difficult to return to baseline levels. Exercise limitation in COPD is multifactorial26 and may lead to increased demand for energy due to high oxygen consumption and increased blood flow demand for locomotor muscles.27

Study strengths and limitationsThis study contributed to understanding different perspectives of people with COPD while performing a multitasking functional test primarily developed to simulate ADLs. The interviews investigated unexplored aspects of the Glittre-ADL test performed without a backpack. As possible limitations of this study, we highlight the small number of females interviewed, consistent with the literature indicating males being more frequently diagnosed with COPD.28 We also underline the difficulty of finding studies addressing the perceptions of individuals with chronic respiratory diseases about the performance of functional tests to compare and discuss the results.

ConclusionThis study provides in-depth information on different perceptions of people with COPD that health professionals may use to select tools for assessing functional capacity. The following perceptions of participants while performing the Glittre-ADL test with and without backpack were reported: dyspnea and fatigue sensation; difficulty using the backpack while performing activities of the test (e.g., squatting); and similarities of test tasks with ADLs despite different perspectives on the degree of ease and expectations on how to perform the test tasks at home. In this sense, listening to the perceptions of individuals after therapeutic interventions may encourage clinicians to improve outcomes by investigating assessment instruments.

The authors thank Provatis Academy Services for providing scientific language revision and editing. This work was supported by FAPEMIG- Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de Minas Gerais and Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior - Brazil (CAPES) Finance Code 001.