Dermatology is a relatively new subdiscipline of physical therapy with growth potential. Therefore, it is important to identify whether professionals from this area have the knowledge and skills required to offer the best available service based on evidence-based practice.

ObjectivesTo describe the self-reported behavior, knowledge, skills, opinion, and barriers related to the evidence-based practice of Brazilian physical therapists from the dermatology subdiscipline.

MethodsAn adapted electronic questionnaire was sent by the Brazilian Association of Dermatology Physical Therapy via email to all registered members. The data were analyzed descriptively.

ResultsThe response rate was 40.4% (101/250). Brazilian physical therapists from the dermatology subdiscipline reported that they update themselves equally through scientific papers and courses, and access preferentially databases that offer scientific papers in the Portuguese language. Respondents believe they have sufficient knowledge to use evidence-based practice, inform patients about treatment options and consider their choices in the decision-making process. However, there were inconsistencies in responses regarding the experience with evidence-based practice during undergraduate or postgraduate degree, as well as having discussions about evidence-based practice in the workplace. The barriers most frequently reported were difficulty to obtain full-text papers, lack of quality of the scientific papers, applicability of the findings into clinical practice, lack of evidence-based practice training and difficulty to understand the statistics.

ConclusionBrazilian physical therapists from the dermatology subdiscipline have positive perceived behavior, believe that they have sufficient knowledge and skills, and have favorable opinion related to evidence-based practice. However, there are inconsistencies related to some aspects of knowledge and skills set.

The term ‘evidence-based practice’ (EBP) is defined as the use of high quality clinical research to inform decisions in clinical practice with regard to the care of individual patients.1 According to the EBP principles, the decision-making process need also to consider the physical therapist's experience and the patient's preferences.1,2 The EBP can be used according to the following steps: (1) formulation of a clinical question, (2) review of the literature, (3) critical appraisal of the evidence, (4) application of the evidence in clinical practice, and (5) appraisal of the implementation of evidence in clinical practice.3,4 While the definition and process in the use of EBP are very well defined, professionals may face different challenges in effectively use it.

Some of the challenges related to the process of using EBP can be associated with physical therapy practice. For example, the use of the best diagnosis or intervention pointed by the literature may require more time, skills and expertise from the physical therapist; it may be more expensive; or, it may not be available in the physical therapist setting.1 Additionally, cultural influences may affect the expectations of patients and professionals or provide contexts less favorable to the use of EBP.1,5 More importantly, a lack of specific knowledge and skills in EBP may make it difficult to use EBP effectively.

Previous studies have described characteristics related to EBP through the perspectives of physical therapists’. A previous systematic review identified the knowledge, skills, behavior, opinions and barriers faced by physical therapists in relation to EBP.6 The review summarized the results of 12 studies (with a total of 6411 participants) from nine countries. The results showed that from three studies reporting knowledge, between 21 and 82% of respondents had received prior information on EBP. From two studies reporting on skills and behavior, nearly half of the sample had used databases to support clinical decision-making. From six studies reporting opinions, most of the participants considered EBP important. The barriers reported most frequently were lack of time, difficulty to understand statistical analysis, lack of support from the employer, lack of resources, lack of interest and a lack of generalization of the results of studies for clinical practice.6 These difficulties were found by professionals from different specialization areas.

Previous studies have investigated perspectives of physical therapists in general, without considering different physical therapy subdisciplines. Dermatology is a recent physical therapy subdiscipline created in 2009 and recognized by the Brazilian physical therapy registration board (Conselho Federal de Fisioterapia e Terapia Ocupacional – COFFITO) in 2010.7 Dermatology assists patients with kinesiological and functional disorders of the skin and related structures, and also preoperative and postoperative conditions.8 Considering it is a subdiscipline that has recently been recognized in physical therapy with significant growth potential, there is a need for a specific investigation into the characteristics of physical therapists in this area with regard to EBP. To date, there has been no study conducted to investigate such characteristics in this subdiscipline. Therefore, this study aims to describe the self-reported behavior, knowledge, opinion and barriers related to EBP experienced by Brazilian physical therapists in the dermatology subdiscipline.

MethodsStudy designThe present study is a cross-sectional descriptive study. The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Instituto Brasileiro de Terapias e Ensino (IBRATE), Curitiba, Parana, Brasil on 12 December 2016 (CAAE: 59741316.9.0000.5229). Participants read and accepted (electronically) the information participant consent form before answering the questionnaire.

ParticipantsThe inclusion criteria were physical therapists, members of the Brazilian Association of Dermatology Physical Therapy up to December 2016, residents in Brazil, with valid certification by the physical therapy registration board of their region. This study received institutional support by the Brazilian Association of Dermatology Physical Therapy that helped in contacting all members and in advertising the study.

Data collection toolThe questionnaire was tested previously in a pilot study9 to guarantee better quality and understanding of the questions. The questionnaire was developed and used in Portuguese language, and divided into the following domains: (1) consent form (1 item); (2) demographic details and educational and professional experience (7 items); (3) area from dermatology (1 item); (4) skills in reading English texts (1 item); and (5) characteristics related to EBP – behavior (5 items), knowledge (9 items), skills and resources (9 items), opinion (5 items), and barriers (15 items). The questionnaire was developed with response options in a five Likert scale between one and five (1=strongly disagree, 2=partially disagree, 3=neutral, 4=partially agree, and 5=strongly agree).9 The full questionnaire is described in Appendix 1.

Data collection proceduresThe Brazilian Association of Dermatology Physical Therapy sent an electronic questionnaire to all members via e-mail (professional and/or personal). The association also advertised the study via their website. The advertisement offered a link to the questionnaire page. The data collection was held from January 2017 to June 2017. The electronic questionnaire was created on the Jot Form of Google Chrome that works in Web Navigator. It is a free service tool for the creation of online forms. The participant started to answer the questionnaire after reading and accepting the participant information consent form. The responses were anonymous. The participant could not progress through the survey without answering all the questions of each page. No reminders were sent. However, we extended the data collection time to optimize the response rate.

Data analysisThe data were analyzed using descriptive statistics, and reported through absolute values, percentages and frequencies. We only considered complete questionnaires in the analysis. The analysis was conducted using the IBM SPSS software (version 22.0 for Windows).

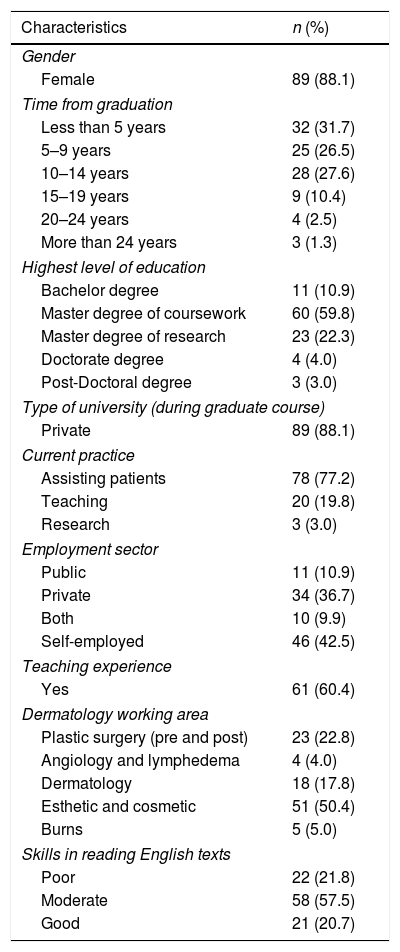

ResultsThe cumulative response rate was 40.4% (101/250). Table 1 describes the demographic characteristics of participants. The majority of participants were women (88.1%), had graduated within the last five years (31.7%) and nine years (26.5%), and held a master of coursework (59.8%). Approximately 77% worked assisting patients, and 50% worked in the esthetic and cosmetic area.

Demographic characteristics of respondents (n=101).

| Characteristics | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Female | 89 (88.1) |

| Time from graduation | |

| Less than 5 years | 32 (31.7) |

| 5–9 years | 25 (26.5) |

| 10–14 years | 28 (27.6) |

| 15–19 years | 9 (10.4) |

| 20–24 years | 4 (2.5) |

| More than 24 years | 3 (1.3) |

| Highest level of education | |

| Bachelor degree | 11 (10.9) |

| Master degree of coursework | 60 (59.8) |

| Master degree of research | 23 (22.3) |

| Doctorate degree | 4 (4.0) |

| Post-Doctoral degree | 3 (3.0) |

| Type of university (during graduate course) | |

| Private | 89 (88.1) |

| Current practice | |

| Assisting patients | 78 (77.2) |

| Teaching | 20 (19.8) |

| Research | 3 (3.0) |

| Employment sector | |

| Public | 11 (10.9) |

| Private | 34 (36.7) |

| Both | 10 (9.9) |

| Self-employed | 46 (42.5) |

| Teaching experience | |

| Yes | 61 (60.4) |

| Dermatology working area | |

| Plastic surgery (pre and post) | 23 (22.8) |

| Angiology and lymphedema | 4 (4.0) |

| Dermatology | 18 (17.8) |

| Esthetic and cosmetic | 51 (50.4) |

| Burns | 5 (5.0) |

| Skills in reading English texts | |

| Poor | 22 (21.8) |

| Moderate | 58 (57.5) |

| Good | 21 (20.7) |

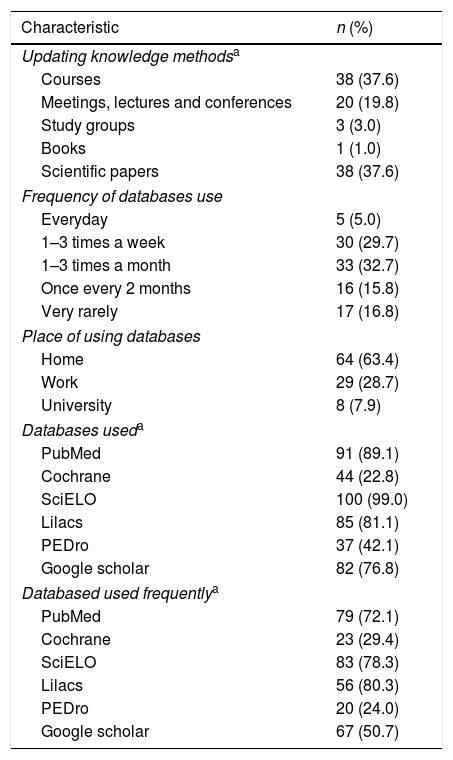

Table 2 describes the behavior of the physical therapists in relation to EBP. Approximately 38% of the respondents update themselves through scientific papers, and the same percentage through courses. According to the use of databases, most of the respondents access databases in the Portuguese language (80.3% use the Lilacs database frequently and 78.3% use the SciELO database frequently); however, 72.1% report using PubMed frequently.

Self-reported behavior related to EBP (n=101).

| Characteristic | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Updating knowledge methodsa | |

| Courses | 38 (37.6) |

| Meetings, lectures and conferences | 20 (19.8) |

| Study groups | 3 (3.0) |

| Books | 1 (1.0) |

| Scientific papers | 38 (37.6) |

| Frequency of databases use | |

| Everyday | 5 (5.0) |

| 1–3 times a week | 30 (29.7) |

| 1–3 times a month | 33 (32.7) |

| Once every 2 months | 16 (15.8) |

| Very rarely | 17 (16.8) |

| Place of using databases | |

| Home | 64 (63.4) |

| Work | 29 (28.7) |

| University | 8 (7.9) |

| Databases useda | |

| PubMed | 91 (89.1) |

| Cochrane | 44 (22.8) |

| SciELO | 100 (99.0) |

| Lilacs | 85 (81.1) |

| PEDro | 37 (42.1) |

| Google scholar | 82 (76.8) |

| Databased used frequentlya | |

| PubMed | 79 (72.1) |

| Cochrane | 23 (29.4) |

| SciELO | 83 (78.3) |

| Lilacs | 56 (80.3) |

| PEDro | 20 (24.0) |

| Google scholar | 67 (50.7) |

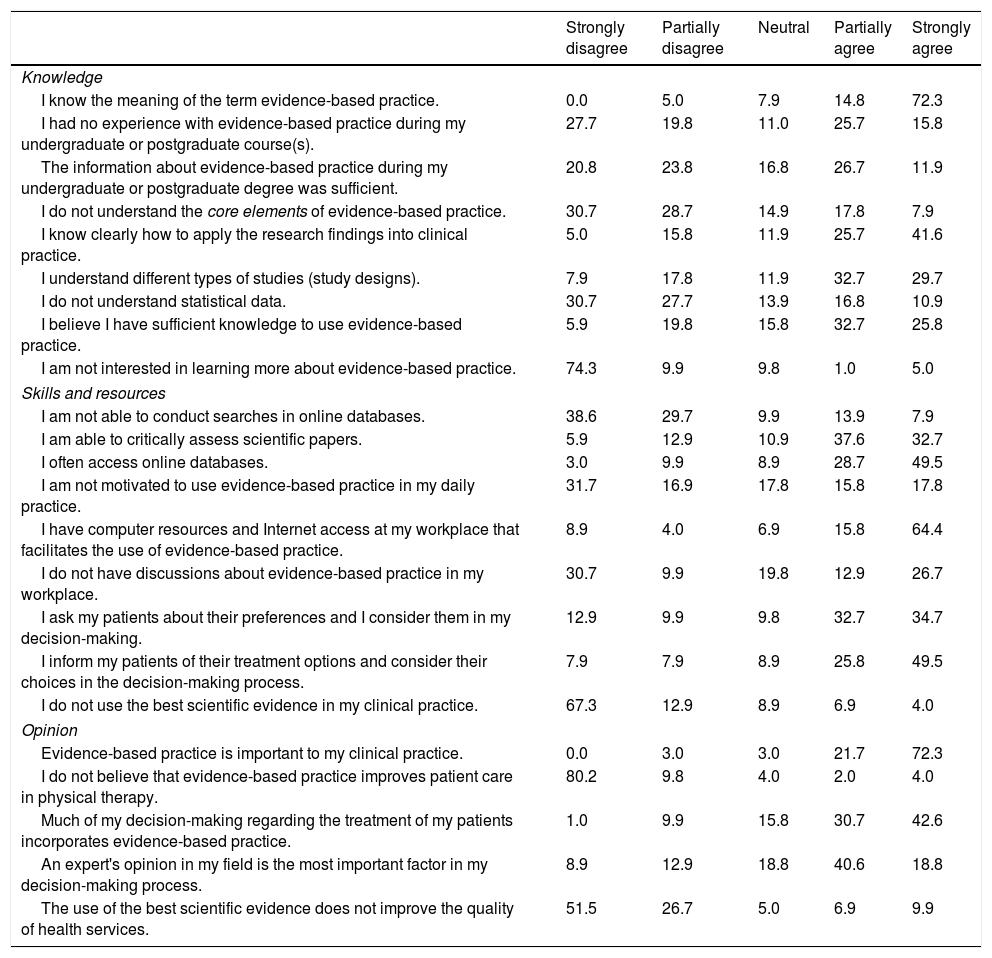

Table 3 describes the self-reported knowledge, skills and resources, and opinions about EBP. The majority of respondents reported that they know the meaning of the term ‘evidence-based practice’ (72.3% strongly agree), clearly understand the use of research findings into clinical practice (67.3% strongly or partially agree), understand different study designs (62.4% strongly or partially agree), and believe they have sufficient knowledge to use EBP (58.4% strongly or partially agree). However, there was inconsistency in the responses regarding experience in EBP during undergraduate or postgraduate degree, and about the information about EBP during the undergraduate or postgraduate degree being sufficient.

Self-reported knowledge, skills and resources, and opinion related to EBP.

| Strongly disagree | Partially disagree | Neutral | Partially agree | Strongly agree | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Knowledge | |||||

| I know the meaning of the term evidence-based practice. | 0.0 | 5.0 | 7.9 | 14.8 | 72.3 |

| I had no experience with evidence-based practice during my undergraduate or postgraduate course(s). | 27.7 | 19.8 | 11.0 | 25.7 | 15.8 |

| The information about evidence-based practice during my undergraduate or postgraduate degree was sufficient. | 20.8 | 23.8 | 16.8 | 26.7 | 11.9 |

| I do not understand the core elements of evidence-based practice. | 30.7 | 28.7 | 14.9 | 17.8 | 7.9 |

| I know clearly how to apply the research findings into clinical practice. | 5.0 | 15.8 | 11.9 | 25.7 | 41.6 |

| I understand different types of studies (study designs). | 7.9 | 17.8 | 11.9 | 32.7 | 29.7 |

| I do not understand statistical data. | 30.7 | 27.7 | 13.9 | 16.8 | 10.9 |

| I believe I have sufficient knowledge to use evidence-based practice. | 5.9 | 19.8 | 15.8 | 32.7 | 25.8 |

| I am not interested in learning more about evidence-based practice. | 74.3 | 9.9 | 9.8 | 1.0 | 5.0 |

| Skills and resources | |||||

| I am not able to conduct searches in online databases. | 38.6 | 29.7 | 9.9 | 13.9 | 7.9 |

| I am able to critically assess scientific papers. | 5.9 | 12.9 | 10.9 | 37.6 | 32.7 |

| I often access online databases. | 3.0 | 9.9 | 8.9 | 28.7 | 49.5 |

| I am not motivated to use evidence-based practice in my daily practice. | 31.7 | 16.9 | 17.8 | 15.8 | 17.8 |

| I have computer resources and Internet access at my workplace that facilitates the use of evidence-based practice. | 8.9 | 4.0 | 6.9 | 15.8 | 64.4 |

| I do not have discussions about evidence-based practice in my workplace. | 30.7 | 9.9 | 19.8 | 12.9 | 26.7 |

| I ask my patients about their preferences and I consider them in my decision-making. | 12.9 | 9.9 | 9.8 | 32.7 | 34.7 |

| I inform my patients of their treatment options and consider their choices in the decision-making process. | 7.9 | 7.9 | 8.9 | 25.8 | 49.5 |

| I do not use the best scientific evidence in my clinical practice. | 67.3 | 12.9 | 8.9 | 6.9 | 4.0 |

| Opinion | |||||

| Evidence-based practice is important to my clinical practice. | 0.0 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 21.7 | 72.3 |

| I do not believe that evidence-based practice improves patient care in physical therapy. | 80.2 | 9.8 | 4.0 | 2.0 | 4.0 |

| Much of my decision-making regarding the treatment of my patients incorporates evidence-based practice. | 1.0 | 9.9 | 15.8 | 30.7 | 42.6 |

| An expert's opinion in my field is the most important factor in my decision-making process. | 8.9 | 12.9 | 18.8 | 40.6 | 18.8 |

| The use of the best scientific evidence does not improve the quality of health services. | 51.5 | 26.7 | 5.0 | 6.9 | 9.9 |

Variables expressed in percentages (%).

The majority of the respondents reported being able to critically assess scientific papers (70.3% strongly or partially agree), often access online databases (78.2% strongly or partially agree), have computer resources and Internet access at the workplace that facilitates the use of EBP (80.2% strongly or partially agree), ask patients about their preferences and consider them in the decision-making (67.4% strongly or partially agree), and inform patients of their treatment options and consider their choices in the decision-making process (75.3% strongly or partially agree). Although there were reports of being encouraged at work to use EBP, there was inconsistency with regard to having discussions about EBP in the workplace.

Opinion related to EBPThe respondents believed that EBP is important in clinical practice (94% strongly or partially agree), and agree that much of the decision-making regarding the treatment of the patients incorporates EBP. However, controversially, respondents reported that experts opinion in the field is the most important factor for their clinical decision-making (59.4% strongly or partially agree).

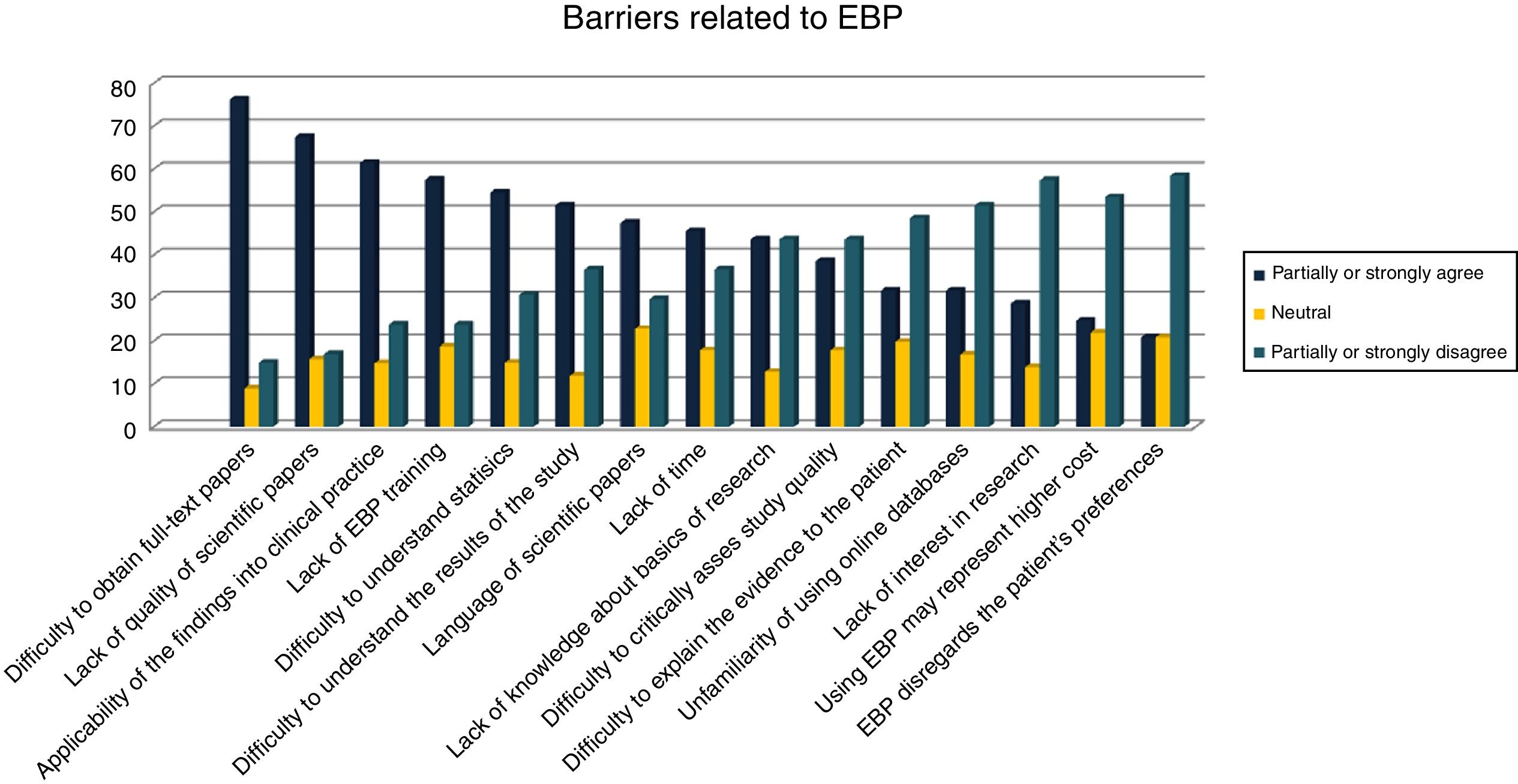

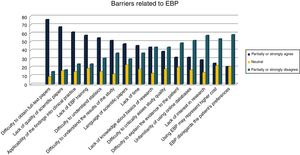

Barriers faced in EBPFig. 1 shows the self-reported barriers related to EBP. The barriers that were reported by respondents most frequently were the difficulty to obtain full-text papers (76.2% strongly or partially agree), lack of quality of the scientific papers (67.4% strongly or partially agree), applicability of the findings into clinical practice (61.4% strongly or partially agree), lack of EBP training (57.5% strongly or partially agree), and difficulty to understand statistics (54.5% strongly or partially agree).

DiscussionSummary of main findingsBrazilian physical therapists from the dermatology subdiscipline reported that they update themselves equally through scientific papers and courses, most of the respondents access databases in the Portuguese language; however, around 70% report using PubMed frequently. Respondents reported that they believe they have sufficient knowledge to use EBP, inform patients of their treatment options and consider their choices in the decision-making process, and are encouraged at work to use EBP. However, there were inconsistencies in the answers regarding experience with EBP during undergraduate or postgraduate degree, and having discussions about EBP in the workplace. Although respondents have favorable opinion related to EBP, they report that expert opinions are the most important factor for their clinical decision-making process. The barriers reported most frequently were the difficulty to obtain full-text papers, lack of quality of the scientific papers, applicability of the findings into clinical practice, lack of EBP training, and difficulty to understand the statistics.

Strengths and weaknesses of the studyWe had a satisfactory response rate (101/250: 40%) when compared to previous studies (20%,10 26%,11 51%,12 and 54%13). We have used different resources to improve data collection by sending questionnaires to both personal and professional e-mail addresses, and by using electronic advertising on the association website (with direct access to the questionnaire). We also extended the data collection time to optimize the response rate. The study also has some limitations. We did not send reminders to participants as an attempt to improve the response rate. And we did not control for participants that could answer the questionnaire more than one time. Unfortunately, many physical therapists in Brazil are not members of physical therapy associations, and therefore we believe we may not have reached all professionals from the dermatology subdiscipline within the nation.

Comparison with other studiesTo date, only two previous studies have identified characteristics related to EBP of Brazilian physical therapists. The first study14 identified whether the physical therapists had skills to review the scientific literature and to use EBP in clinical practice. The study reported that physical therapists have positive behavior related to EBP and are interested in improving their skills.14 This study was a pilot with only 67 physical therapists from one state in Brazil. The second study9 identified the perceived knowledge, skills, resources, opinions and barriers related to EBP of 316 Brazilian physical therapists. Respondents also believed they have the knowledge and skills necessary to apply EBP and also had favorable opinion about it.9 The study also pointed out some inconsistencies in the answers, such as understanding the core elements of EBP and understanding statistical data.9 This study had a large sample; however, it considered only one state in Brazil and only 12.1% of the sample was from the dermatology subdiscipline. The results of our study also agree with existing studies from other countries.

In comparison to studies around the world, differently to our study, 82% of physical therapists of a study from USA,15 more than 50% of a study from Philippines,16 and 44.5% of a study from Canada17 reported that they received information about EBP during their undergraduate or postgraduate degrees. Controversially, 89% of physical therapists of a study from Japan,18 70.2% of a study from Saudi Arabia, and 30.8 of a study from Germany11 had no formal EBP training. Physical therapists from Canada,17 USA,15 Sweden,19 Japan,18 France,12 Sweden,20 Colombia,21 and Germany11 also agree that EBP is necessary to clinical practice. The main barrier reported by previous studies was lack of time.12,13,15,17,19,20 The study from France also reported no access to full articles as an important barrier. The studies from USA,15 Canada,17 Sweden,19 and Colombia21 also reported applicability of the findings into clinical practice as an important barrier. And the studies from USA,15 Canada,17 Philippines,16 and Colombia21 also reported inability to understand statistics as an important barrier.

Meaning of the studyAlthough respondents reported that they have sufficient knowledge to use EBP, there were inconsistencies in the answers regarding experience with EBP during their degrees, and regarding having discussions about EBP in the workplace. The most important barrier was difficulty to obtain full-text papers. These findings demonstrate implications in three possible levels. First, the need of educational strategies related to EBP – as part of the undergraduate degree, master of coursework of dermatology degree, and continuing education or short courses. Second, workplaces may encourage the use of high-quality research to guide clinical practice. This can be done by organizing times for discussions about patients focused on EBP principles, or discussions about specific issues such as methodology or statistics, and by offering facilities such as computer resources and Internet access at the workplace. And finally, there are some possible options to get full-text papers for free. Bireme22 grants free access to many databases. Capes e-journal web portal23 grants access to public universities and few private universities, along with other web portals that provide access to scientific journals. However, the physical therapists need proper training and good English language reading skills to be able to use these databases.

ConclusionBrazilian physical therapists from the dermatology subdiscipline have positive perceived behaviors related to EBP, believe they have sufficient knowledge and skills to use EBP, and have favorable opinion related to it. However, there are current inconsistencies related to some aspects of their knowledge and skill set. The barriers reported most frequently were the difficulty to obtain full-text papers, lack of quality of the scientific papers, applicability of the findings into clinical practice, lack of EBP training, and difficulty to understand statistics.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.

CAPES (Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior), Ministry of Education of Brazil. This study was supported by the Brazilian Association of Dermatology Physical Therapy (ABRAFIDEF), who helped in the selection and recruitment of participants. We thank all the participants who participated in the study.