In both the United Kingdom (UK) and Brazil, women undergoing mastectomy should be offered breast reconstruction. Patients may benefit from physical therapy to prevent and treat muscular deficits. However, there are uncertainties regarding which physical therapy program to recommend.

ObjectiveThe aim was to investigate the clinical practice of physical therapists for patients undergoing breast reconstruction for breast cancer. A secondary aim was to compare physical therapy practice between UK and Brazil.

MethodsOnline survey with physical therapists in both countries. We asked about physical therapists’ clinical practice.

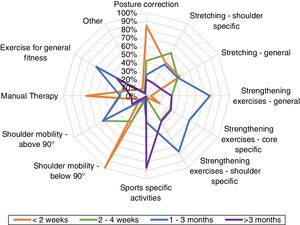

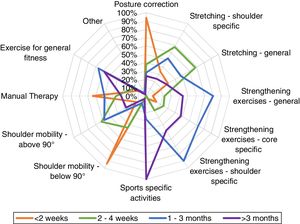

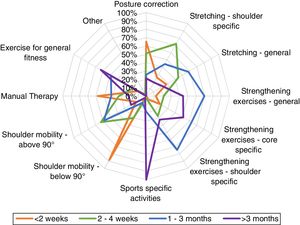

Results181 physical therapists completed the survey, the majority were from Brazil (77%). Respondents reported that only half of women having breast reconstruction were routinely referred to physical therapy postoperatively. Contact with patients varied widely between countries, the mean number of postoperative sessions was 5.7 in the UK and 15.1 in Brazil. The exercise programs were similar for different reconstruction operations. Therapists described a progressive loading structure over time: range of motion (ROM) was restricted to 90° of arm elevation in the first two postoperative weeks; by 2–4 weeks ROM was unrestricted; at 1–3 months muscle strengthening was initiated, and after three months the focus was on sports-specific activities.

ConclusionOnly half of patients having a breast reconstruction are routinely referred to physical therapy. Patients in Brazil have more intensive follow-up, with up to three times more face-to-face contact with a physical therapist than in the UK. Current practice broadly follows programs for mastectomy care rather than being specific to reconstruction surgery.

Breast cancer is the most common type of cancer in women with 55,439 and 85,620 new cases diagnosed in 2018 in the UK and in Brazil, respectively.1 However, patients are now living longer; five-year survival has improved to 86% in the UK and 75% in Brazil.2 Patients treated for breast cancer can experience a long, complex, and distressing healthcare journey, which may include surgery, chemotherapy, radiotherapy, immunotherapy, and endocrine treatment.3 These treatments can cause long-term problems; approximately 35% of patients report pain and limitations of shoulder and arm function more than three years after their breast cancer treatment.4 Almost all women will require surgical treatment and up to 40% undergo mastectomy.5 Mastectomy can negatively affect body image, self-esteem, and health-related quality of life (QoL).6 Several studies have demonstrated that breast reconstruction may improve patients’ psychological and emotional wellbeing.6,7 Current UK guidance recommends that all women undergoing mastectomy should be offered either immediate or delayed breast reconstruction.8 Since 2013, patients with breast cancer in Brazil have the right to request breast reconstruction in the public health service.9 The rates of breast reconstruction are increasing year on year with a quarter of women in the UK now electing to undergo immediate reconstruction. In Brazil, there has been a 58% increase in the number of breast reconstructions performed in the public health service between 2008 and 2014.10

Reconstruction surgery is complex and different approaches are used; surgical techniques can broadly be divided into procedures using implants or autologous tissue.11 Each type of breast reconstruction can affect postoperative function differently. For instance, women undergoing latissimus dorsi reconstruction are at greater risk of shoulder range of motion (ROM) deficits; with up to 73% of patients reporting postoperative difficulties with daily activities involving arm movement.12 Implant-based reconstruction may impair pectoralis muscle strength13 and abdominal flaps may reduce trunk muscle strength by 23%.14 There is some evidence to suggest that newer muscle sparing approaches using perforators flaps (e.g. deep or superficial inferior epigastric artery flaps) may result in better functional outcomes.11,15 The most common type of reconstruction in the UK involves the use of implants (36%) for immediate reconstruction and autologous tissue (32%) for delayed reconstructions.16 In Brazil, the most common method of reconstruction involves autologous tissue (66%).10

Physical therapy and structured home-based exercise programs may help to prevent or reduce pain and morbidities related to the arm, shoulder, and other joints .17,18 However, there is still uncertainty regarding the optimal content and timing of exercise prescription after reconstruction. Physical therapy may also support patients in meeting the minimum amount of physical activity recommended per week. A systematic review (n = 6 studies, 1607 participants) found that at two years post-diagnosis, most women (91%) did not meet the recommended guidelines for weekly physical activity.19

The current guidelines of the UK-based Association of Breast Surgery (ABS) and the British Association of Plastic Reconstructive and Aesthetic Surgeons (BAPRAS) state that all patients should have early access to specialist physical therapy, including pre-operatively, to prevent and treat upper limb morbidities, particularly when extensive reconstruction surgery is required.20 However, these societies also acknowledge that there is very limited evidence for physical therapy after reconstruction surgery and therefore current guidelines and recommendations are largely based on expert opinion and clinical experience.20

In Brazil, the national policy for cancer care states that high-complexity cancer care units must have multidisciplinary teams, which may involve physical therapists.21 In 2003, the Brazilian Ministry of Health published a consensus document called Breast Cancer Control.22 The document brings information on prevention, early diagnosis, and treatment. It recommends that physical therapy should be offered before surgery to identify any risk factors for postoperative complications. Physical therapy should then continue in the immediate post-operative stage and during adjuvant therapy to identify, prevent, and mitigate problems such as acute and chronic pain, lymphoedema, functional impairment, and respiratory complications.22 The consensus also suggests that home-based exercises and self-massage should be used to control pain. However, there is no specific advice for the care of patients undergoing breast reconstruction, and similar to the UK guidelines, these recommendations were based on expert opinion only.22 The lack of information about current physical therapy care after breast reconstruction may contribute to inconsistency in patterns of care within and across different healthcare systems.

Given the lack of evidence, we wanted to identify whether a) patients undergoing breast reconstruction are routinely referred to physical therapy; b) the content, timing of delivery, and structure of physical therapy-led rehabilitation programs; c) the setting and format of current physical therapy care; and d) recommendations for exercise progression over the postoperative period. Therefore, the aim of this cross-sectional study was to investigate the characteristics and content of physical therapy-led rehabilitation programs delivered to patients undergoing breast reconstruction. A secondary objective was to compare the characteristics of physical therapy care in two healthcare settings, the UK and Brazil. Both countries offer universal health coverage, have a free-at-point of care national health service (NHS), and recommend that breast reconstruction should be offered to women undergoing mastectomy.

MethodsWe carried out an open, voluntary online survey in the UK (September–October 2018) and in Brazil (January–March 2019). The survey was developed in three stages: firstly, the authors reviewed the literature and consulted with at least one specialist cancer physical therapist from each nation to identify the key elements included in standard perioperative care. Based on this initial stage, a first draft of the questionnaire was developed. Secondly, the survey was piloted with a small sample of clinicians involved with the care of this patient population. Adaptations were made based on clinician feedback. The third stage was to undertake another pilot phase to test the online platform and layout; four physical therapists were involved across multiple development stages. Using their feedback, we then created the final version of the questionnaire. This study was given ethical approval in the UK by the Biomedical and Scientific Research Ethics Committee, University of Warwick, Coventry (REGO-2018-2217) and by the Universidade de Campinas, Campinas, São Paulo, Brazil (03872318.3.0000.5404). Participants were asked to consent to take part in the study by ticking a box before proceeding to complete the survey. We followed the Checklist for Reporting Results of Internet E-Surveys (CHERRIES) to report our findings.23

Two versions of the questionnaires (English and Portuguese, available at https://wrap.warwick.ac.uk/123565) were produced and data were stored via the online platform Qualtrics (Qualtrics, Provo, UT, USA). The final survey comprised 41 questions, across 21 screens/pages (one to two questions per page), focusing on physical therapists’ clinical practice for the management of patients undergoing breast reconstruction. Questions and items followed the same order for every participant. We did not randomize or alternate items nor did we record the time taken to complete the survey. We included three example clinical cases to standardize the context for responses for three commonly used breast reconstruction procedures. Physical therapists were invited to describe the routine care of women undergoing either silicone implant, latissimus dorsi (LD) or deep inferior epigastric artery (DIEP) flaps. Each case was presented as follows: “A woman, 55 years, had a unilateral breast (dominant side) reconstruction using a ____. Her overall health is good and she had no postoperative complications.”

Therapists working across both public and private sectors could respond separately where usual care pathways differed. Before submitting their answers, participants could review their responses by using the ‘left arrow/back’ button. Given that no identifiable data were collected, it was not possible to check for duplicate submissions. However, if the participant decided to start the survey then complete at a later date, the online platform would automatically take the participant back to the relevant section. The online platform had the option of a Survey ID cookie to minimize duplications. We manually checked for completeness once questionnaires were submitted.

SamplingGiven the difficulties in determining the sampling frame of total number of physical therapists involved with the care of patients with breast cancer across both countries, it was not possible to calculate a sample size. Hence, we used a convenience sampling. An invitation to complete the online survey was posted on the UK Chartered Society of Physical Therapy Oncology group website and advertised on the news section of the UK Association of Chartered Physical therapists in Oncology and Palliative Care website. In Brazil, the advert was posted on the Brazilian Society of Physical Therapy in Women´s Health website. These websites are the main source of news related for physical therapists working in oncology and palliative care. In addition to these websites, social media was used to broaden the reach of the survey in both countries. No invitations were sent directly by standard post, we only used online advertisement. The text used for advertising the survey is provided as Supplementary material.

Eligibility criteriaTo be eligible , participants had to be a registered physical therapist, currently practicing either in the UK or in Brazil and involved with the care of patients undergoing breast reconstruction. The first section of the survey included a mandatory screening section to confirm inclusion criteria and obtain consent to participate. Participants did not receive any incentives to participate or complete the survey. At the end of the survey, participants had the option of downloading a copy of their responses.

Data analysisData were imported from Qualtrics into Excel (Microsoft Corp, Redmond, WA, USA) for descriptive statistical analyses. No statistical methods were used to adjust for representativeness. Partial and complete surveys were included in the final analysis with number of missing data reported. We used radar graphs to illustrate findings for each of the three reconstruction methods (silicone implant, LD, and DIEP). No Log file analysis was performed.

ResultsResponse ratesA total of 265 (Brazil n = 200; UK n = 65) accesses to the questionnaire link were recorded; however, 181 entries were logged. The majority of respondents were from Brazil (139/181; 77%). In the UK, a higher proportion of responding physical therapists worked in the public sector (30/42; 71%), while in Brazil, responding therapists were more equally distributed between public (61/136; 45%) and private sectors (71/136; 52%) (Table 1). We did not record the number of unique site visitors, therefore, we could not compare survey view rates, participation, and completion rates.

Clinical experience and training of responding physical therapists.

| UK N (%) | Brazil N (%) | Total N (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Completed training in breast cancer care | |||

| Yes | 34 (80.9) | 120 (86.4) | 154 (85.1) |

| No | 8 (19.1) | 18 (12.9) | 26 (14.4) |

| Missing | 0 (0) | 1 (0.7) | 1 (0.5) |

| Total | 42 (100) | 139 (100) | 181 (100) |

| Type of traininga | |||

| Continuous Professional Development | 28 (48.3) | 143 (51.1) | 171 (50.6) |

| Post-graduate module(s) | 7 (12.0) | 96 (34.3) | 103 (30.6) |

| Post-graduate courses (MSc or PhD) | 4 (6.9) | 32 (11.4) | 36 (10.6) |

| Other (short duration courses or in-house training) | 19 (32.8) | 9 (3.2) | 28 (8.2) |

| Total | 58 (100) | 280 (100) | 338 (100) |

| Experience of treating patients with breast cancer (years) | |||

| < 5 years | 11 (26.2) | 60 (43.2) | 71 (39.2) |

| Between 6 and 10 years | 16 (38.1) | 36 (25.9) | 52 (28.7) |

| Between 11 and 15 years | 7 (16.7) | 12 (8.6) | 19 (10.5) |

| >15 years | 8 (19.0) | 31 (22.3) | 39 (21.6) |

| Missing | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Total | 42 (100) | 139 (100) | 181 (100) |

| Work sector | |||

| Public service | 30 (71.4) | 61 (43.9) | 91 (50.3) |

| Private practice | 11 (26.2) | 71 (51.1) | 82 (45.3) |

| Both | 1 (2.4) | 4 (2.9) | 5 (2.8) |

| Missing | 0 (0) | 3 (2.1) | 3 (1.6) |

| Total | 42 (100) | 139 (100) | 181 (100) |

| Number of patients with breast cancer treated per year | |||

| < 20 | 16 (38.0) | 60 (43.2) | 76 (42.0) |

| Between 20 and 50 | 12 (28.6) | 41 (29.5) | 53 (29.3) |

| >50 | 13 (31.0) | 31 (22.3) | 44 (24.3) |

| Missing | 1 (2.4) | 7 (5.0) | 8 (4.4) |

| Total | 42 (100) | 139 (100) | 181 (100) |

Most clinicianstreated, on average, less than 20 patients with breast cancer per year (76/173; 44%) although a quarter of respondents (44/173; 25%) treated more than 50 patients per annum (Table 2). Half of responding physical therapists from each country stated that despite caring for patients with breast cancer, fewer than half of their patients routinely had breast reconstruction. Half of therapists (80/164; 49%) responded that patients were routinely referred to physical therapy postoperatively but only 7% (12/164) were routinely referred for care both pre and postoperatively. Approximately one third (61/164; 37%) reported that patients were not routinely referred for physical therapy at all. The main reasons for referral to physical therapy were for management of complications after surgery (53/116; 46%), followed by referrals for patients with a history of shoulder problems before having a breast reconstruction (30/116; 26%).

Clinical practice characteristics of responding physical therapists.

| UK N (%) | Brazil N (%) | Total N (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Proportion of breast cancer patients with breast reconstruction treated by physical therapists per year | |||

| Less than half | 19 (45.2) | 64 (46.0) | 83 (45.8) |

| Half | 16 (38.1) | 35 (25.2) | 51 (28.2) |

| More than half | 5 (12.0) | 30 (21.6) | 35 (19.3) |

| Missing | 2 (4.7) | 10 (7.2) | 12 (6.7) |

| Total | 42 (100) | 139 (100) | 181 (100) |

| Routine referral of breast reconstruction patients to physical therapy | |||

| Yes, preoperatively only | 2 (4.8) | 0 (0) | 2 (1.1) |

| Yes, pre and postoperatively | 3 (7.1) | 9 (6.5) | 12 (6.6) |

| Yes, postoperatively only | 14 (33.3) | 66 (47.5) | 80 (44.2) |

| No, not routinely seen | 16 (38.0) | 45 (32.4) | 61 (33.7) |

| I don't know | 5 (12.0) | 4 (2.9) | 9 (5.0) |

| Missing | 2 (4.8) | 15 (10.7) | 17 (9.4) |

| Total | 42 (100) | 139 (100) | 181 (100) |

| Reasons for referral to physical therapy (if not routinely seen by a physical therapist)a | |||

| Shoulder problems before surgery | 6 (24.0) | 24 (26.4) | 30 (25.9) |

| Complications after surgery | 13 (52.0) | 40 (44.0) | 53 (45.7) |

| Other physical problems | 3 (12.0) | 19 (20.9) | 22 (19.0) |

| Age | 0 (0) | 4 (4.4) | 4 (3.4) |

| Other | 3 (12.0) | 4 (4.4) | 7 (6.0) |

| Total | 25 (100) | 91 (100) | 116 (100) |

| Average number of face-to-face appointments per patient | |||

| Public; mean (SD) | 4.3 ± 2.7 | 13.7 ± 8.1 | – |

| Private; mean (SD) | 7.2 ± 3.5 | 16.6 ± 8.7 | – |

| Overall; mean (SD) | 5.7 ± 3.1 | 15.1 ± 8.4 | – |

| Main barriers when caring for patients with breast reconstructiona | |||

| Patients psychological health | 9 (17.3) | 22 (8.1) | 31 (9.6) |

| Lack of patient compliance | 7 (13.5) | 51 (18.8) | 58 (18.0) |

| Lack of time | 2 (3.8) | 10 (3.7) | 12 (3.7) |

| Lack of training | 4 (7.7) | 23 (8.5) | 27 (8.4) |

| Lack of research evidence | 4 (7.7) | 16 (5.9) | 20 (6.2) |

| Limited number of appointments | 13 (25.0) | 0 (0) | 13 (4.0) |

| Patient unable to pay for physical therapy | 1 (1.9) | 60 (22.1) | 61 (18.9) |

| Delayed start of physical therapy | 1 (1.9) | 85 (31.4) | 86 (26.6) |

| Other (e.g. lack of referral to physical therapy, patient fatigue, or postoperative complications) | 11 (21.2) | 4 (1.5) | 15 (4.6) |

| Total | 55 (100) | 271 (100) | 323 (100) |

In both countries, the most frequent method of breast reconstruction was implants, followed by LD flaps (Table 3). We observed a marked difference in the mean number of face-to-face treatment sessions between countries; in the UK, the mean number of sessions was 5.7 compared to 15.1 in Brazil. Physical therapists from Brazil reported that the main barriers to providing adequate postoperative care after breast reconstruction were the delayed start of physical therapy (85/271; 31%) and limited patient finances (60/271; 22%). In the UK, physical therapists cited limited number of appointments (13/55; 25%) and other factors (11/55; 21%), such as lack of referral to physical therapy, patient fatigue, and postoperative complications.

Frequency of types of breast reconstruction managed by physiotherapists in clinic.

| Reconstruction method n (%) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency | Country | Implant | LD | TRAM | DIEP | SIEA | TUG or TMG | SGAP or IGAP |

| Do not see | UK | 4 (9.5) | 0 (0) | 8 (19.0) | 12 (28.5) | 26 (61.9) | 28 (66.6) | 30 (71.4) |

| BR | 0 (0) | 10 (7.2) | 24 (17.2) | 81 (58.3) | 83 (59.7) | 91 (65.5) | 98 (70.5) | |

| Rarely | UK | 3 (7.1) | 5 (11.9) | 18 (42.9) | 9 (21.4) | 5 (11.9) | 3 (7.1) | 2 (4.7) |

| BR | 10 (7.2) | 45 (32.3) | 56 (40.3) | 22 (15.9) | 21 (15.1) | 17 (12.2) | 8 (5.8) | |

| Sometimes | UK | 18 (42.9) | 18 (42.9) | 5 (11.9) | 6 (14.3) | 2 (4.7) | 1 (2.4) | 1 (2.4) |

| BR | 39 (28.0) | 42 (30.2) | 20 (14.4) | 6 (4.3) | 2 (1.5) | 1 (0.7) | 1 (0.7) | |

| Often | UK | 4 (9.5) | 6 (14.2) | 2 (4.7) | 6 (14.3) | 0 (0) | 1 (2.4) | 0 (0) |

| BR | 45 (32.4) | 17 (12.3) | 11 (8.0) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.7) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.7) | |

| Very often | UK | 4 (9.5) | 4 (9.5) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| BR | 25 (18.0) | 1 (0.7) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Missing | UK | 9 (21.5) | 9 (21.5) | 9 (21.5) | 9 (21.5) | 9 (21.5) | 9 (21.5) | 9 (21.5) |

| BR | 20 (14.4) | 24 (17.3) | 28 (20.1) | 30 (21.5) | 32 (23.0) | 30 (21.6) | 31 (22.3) | |

| UK total | 42 (100) | 42 (100) | 42 (100) | 42 (100) | 42 (100) | 42 (100) | 42 (100) | |

| BR total | 139 (100) | 139 (100) | 139 (100) | 139 (100) | 139 (100) | 139 (100) | 139 (100) | |

LD, latissimus dorsi; TRAM, transverse rectus abdominis; DIEP, deep inferior epigastric perforator; SIEA, superficial inferior epigastric artery; TUG, transverse upper gracilis; TMG, transverse musculocutaneous gracilis; SGAP, superior gluteal artery perforator; IGAP, inferior gluteal artery perforator.

Clinicians from both countries were very similar with regards to the types and format of exercises prescribed at each postoperative phase, therefore, we present the combined data. The physical therapy programs for the three reconstruction procedures are displayed in Figs. 1–3. In the first two weeks postoperatively, exercises for shoulder mobility were restricted to below 90° of arm elevation; posture correction and manual therapy were the most frequent components covered in these early therapy sessions. Between two to four weeks postoperatively, exercises for shoulder mobility above 90° and shoulder-specific stretching were more common. From one to three months after surgery, therapists would then prescribe general strengthening, shoulder-specific, and core-specific strengthening exercises. After three months, the focus was on sport-specific activities with less attention to other modalities.

This is the first survey to our knowledge to investigate the characteristics of physical therapy care across the different postoperative stages after breast reconstruction for breast cancer. We explored physical therapy care in two different countries where the public health service has a broadly similar organizational structure, despite variation in underlying patient biosociodemographic characteristics and population size (the UK-NHS serves 67 million people compared to 211 million in Brazil).24

Overall, we found important gaps regarding physical therapy care, evidenced by the high number of patients who are not routinely referred to physical therapy care after breast reconstruction surgery, despite increasing numbers of women undergoing these procedures. Unlike mastectomy and breast conserving surgery, breast reconstructions are associated with prolonged hospital stays, often up to one week.25 We found that patients were only referred for physical therapy if a surgical complication had developed or for a pre-existing shoulder problem .

In the UK, the reason for the lack of referral to physical therapy may be due to clinical teams adhering to the current National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines. These guidelines recommend that patients with pre‑existing shoulder conditions should be identified preoperatively to inform treatment decisions; if these patients present with a persistent reduction in arm and shoulder mobility after treatment, they should then be referred to physical therapy.8 However, Woo et al.26 observed 420 patients following breast reconstruction over a mean follow-up of 52 months; they identified various other risk factors for shoulder problems besides a preoperative history of shoulder problems. These included reconstruction procedure, older age, and neoadjuvant chemotherapy. The authors also reported that initiating physical therapy within two months of reconstruction surgery reduced the risk of sustained shoulder morbidity in the longer term (odds ratio: 7.2, 95% CI: 1.4, 36.7).26 Although UK health care teams may follow NICE recommendations, the advice for postoperative care from both the ABS and BAPRAS contrast with those of NICE.20 Their latest guidelines state that all patients should have early access to physical therapy to prevent and treat upper limb morbidities. Therefore, these conflicting guidelines lead to uncertainties and inequalities in the care of patients with breast cancer. This was recently highlighted by a report from the UK All-party Parliamentary Group Report.27

In Brazil, the Comissão Nacional de Incorporação de Tecnologias (CONITEC) guidelines for breast cancer treatment and management do not contain any specific recommendation or information regarding physical therapy care.9 The consensus document from the Brazilian Ministry of Health recommends that physical therapy should be routinely incorporated before and after breast cancer surgery. However, there is no specific advice for the care of patients undergoing breast reconstruction.22 There is a lack of information in the Brazilian guidelines, in addition to the limited information regarding the number of physical therapists working with oncology patients in Brazil. This may impact the number of referrals made to physical therapists by oncology teams and may contribute to inequalities in patient care. Better integration of physical therapists within the multidisciplinary oncology team and into the treatment pathway of patients having breast reconstruction could improve awareness, increase referral rates, and potentially reduce complications after surgery.28

One of the main differences we found between the healthcare systems was the number of face-to-face appointments offered to patients. Brazilian physical therapists have, on average, three times the number of contacts with patients compared to those in the UK, even within the public sector. The limited access to physical therapy sessions was highlighted by UK physical therapists as the main barrier to care, which may be due to the increasing demand and pressure on the financially constrained NHS.29,30 Physical therapy services in the UK are centrally funded by the Department of Health. Thus, the proposed number of sessions is largely based on what is possible for delivery within the NHS. There is currently limited evidence regarding what rehabilitation programs should offer, and similarly, limited or no evidence to support the hypothesis that a higher number of sessions is substantially more clinically and cost-effective in the long-term.31,32

Although the number of sessions offered and available to patients is considerably higher in Brazil, the main barriers to providing care included the delayed presentation to physical therapy and limited ability to pay for private treatment. These barriers may be linked to the lack of physical therapists working in primary care and outpatient settings in the Brazilian public sector.33 According to Rodes et al.,33 there is a higher concentration of physical therapists working in medium to high complexity services (secondary care) and a shortage of professionals in primary care. Therefore, patients seek out private treatment and thus finances may constrain access to appropriate physical therapy treatment. Physical therapy in oncology is a relatively recent clinical specialty in Brazil; it was accredited in 2009 by The Brazilian Federal Council for Physical Therapy and Occupational Therapy (COFFITO). Our data reflect the recent accreditation of this physical therapy specialty; almost half of the respondents from Brazil had fewer than five years of experience of treating patients with breast cancer.34

The physical therapy programs described by the survey participants were broadly similar for the different reconstruction methods and followed similar principles of exercise progression for patients undergoing mastectomy.35,36 For instance, therapists reported that they limited shoulder mobility exercises to 90° of arm elevation in the first two weeks after surgery to avoid wound healing complications while maintaining shoulder mobility.36 Once wound healing had occurred, care from weeks two to four postoperatively allowed unrestricted shoulder movement aiming to improve shoulder ROM.35 By one month postoperatively, strengthening exercises were allowed and after three months, sports activities were actively encouraged. This progressive approach is consistent with what is reported in other studies.18,37–39 A progressive exercise protocol is advocated to be better than usual care for improving function and pain at six months,38 muscle strength at 12 months,37 and does not increase the risk of complications, such as lymphoedema at 12 months.39 Although there are studies suggesting the benefits of exercise for patients with breast cancer, these studies are generally of low methodological quality and they do not include patients undergoing breast reconstruction.36,40

The evidence for physical therapy following breast reconstruction is scarce; to our knowledge, there are no high-quality systematic reviews or randomized controlled trials investigating the clinical and cost-effectiveness of physical therapy for this patient population. A literature review from Teixeira and Sandrin41 assessed physical therapy care following oncological breast reconstruction; however, the review did not follow the PRISMA42 statement and was methodologically limited. The review did not include a clear definition of their patient population, interventions, comparisons, and outcomes. Furthermore, risk of bias of included studies was not undertaken.

One randomized controlled trial from Futter et al.43 investigated the effect of pre-operative abdominal strengthening to prevent abdominal complications in 93 women undergoing a DIEP flap. They found that abdominal exercises had a positive impact on well-being before surgery; however, this trial lacked methodological rigor. Physical therapy following breast reconstruction should not only follow the general principles of rehabilitation following mastectomy, but clinicians must be aware of the specificities of each reconstruction method to tailor exercises accordingly. Patients having an LD reconstruction have a higher risk of developing shoulder problems than other methods of reconstruction using implants or autologous tissue. Additional exercises may be needed for the abdominal and back muscles after transverse rectus abdominis (TRAM) reconstruction.44 Rindom et al.45 randomized 50 women to either a LD or a thoracodorsal artery perforator (TAP) flap reconstruction; patients allocated to the TAP group showed better shoulder function at 12 months. Woo et al.26 found similar results with their cohort of 430 patients; forty-three percent of those having LD reconstruction developed shoulder morbidity at four years post-surgery, compared to 23% after expander-implant and 14% after DIEP surgery. Further high-quality randomized clinical trials are needed to assess the clinical and cost-effectiveness of physical therapy programs designed for each reconstruction surgery.

LimitationsThe limitations of our study include the low overall number of survey respondents and a discrepancy in the proportion of respondents from each country. However, it is difficult to accurately estimate the number of physical therapists who regularly treat patients with breast cancer in both countries. It is, therefore, challenging to estimate sample representativeness with any certainty. Donnelly et al.46 conducted a survey to investigate physical therapy management of cancer related-fatigue for various types of cancer; the authors identified 102 physical therapists from the UK who stated that they would use exercises for patients with breast cancer. Similarly, O'Hanlon and Kennedy47 completed a survey of the Irish members of the Chartered Physical therapists in Oncology and Palliative Care. This survey investigated exercise prescription for cancer patients but the findings were based on only 35 responses. We found no publications or examples of questionnaire surveys of physical therapists working within oncology in Brazil. According to Matsumura et al.,48 there were 206,170 registered physical therapists in Brazil in 2016, however, oncology rehabilitation is likely to be a smaller specialized subset of all registrations. Another factor that may have affected the number of respondents was the length of the survey, which may have impacted the response rate. Nevertheless, this is the first survey to our knowledge to investigate practice of physical therapists caring for patients undergoing oncological breast reconstruction. There is a need to design and test physical therapy programs for patients undergoing breast reconstruction.

ConclusionThe majority of physical therapists caring for patients having a breast reconstruction treat a low number of cases per year and overall referral to physical therapy services is low given the increasing volume of breast reconstruction surgeries. Patients in Brazil are more likely to have a higher number of sessions with therapists compared to the UK, with a three-fold difference in face-to-face appointments. The most frequent method of breast reconstruction reported by physical therapists across both countries was silicone implants. Current physical therapy programs follow the same general principles of postoperative care after mastectomy.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.

We would like to thank Shelley Potter, Clare Lait and Catherine Hegarty for their feedback on early versions of the survey. We also would like to thank the Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo (FAPESP process number 2018/06161-0).