Reablement is a team-based person-centered health and social care model, most commonly available for community-dwelling older adults. Understanding the components of reablement and how it is delivered, received, and enacted facilitates best evidence and practice. Determining behavior change techniques (BCTs) or strategies is an important step to operationalize implementation of reablement.

ObjectiveWe conducted a scoping review of peer-reviewed literature to identify BCTs used within reablement studies.

MethodsWe registered our study with the Joanna Briggs Institute and conducted five database searches. Inclusion criteria were peer-reviewed studies focused on adults and older adults without significant cognitive impairment or dementia receiving reablement, and all study designs, years, and languages. We excluded studies focused on reablement for people with dementia or reablement training programs. The last search was on April 8, 2021. Two authors screened independently at Level 1 (title and abstract) and 2 (full text). Two authors adjudicated BCTs for each study, and a third author confirmed the final list.

ResultsWe identified 567 studies (591 publications) and included 21 studies (44 publications) from six global locations. We identified 27 different BCTs across all studies. The three most common BCTs for reablement were goal setting (behavior), social support (unspecified), and instruction on how to perform a behavior.

ConclusionsWe highlight some behavioral components of reablement and encourage detailed reporting to increase transparency and replication of the intervention. Future research should explore effective BCTs (or combinations of) to include within reablement to support health behavior adoption and maintenance.

In the rapidly growing field of implementation science, a distinction is made between a clinical service (or research intervention) and how it is delivered.1 Implementation research differs from intervention research and is defined as the “scientific study of methods to promote the systematic uptake of research findings and other evidence-based practices into routine practice, and, hence, to improve the quality and effectiveness of health services. (p.1)”1 There are often challenges with healthcare delivery ranging from individual (ability, motivation, preferences, etc.) to system-wide factors (resources), all of which may impact how people adopt and maintain health behaviors. Health providers’ and patients’ (or people's) behavior is one important implementation factor needed to determine the effectiveness of an intervention, and possible ways to scale up and spread the implementation of a clinical service.

Reablement is a health and social model of care, frequently seen in the public setting in the United Kingdom and Scandinavia.2 Reablement has many strengths and is focused on person centered care to support people to be autonomous and independent in their daily life activities. Systematic reviews on the effectiveness of reablement highlight mixed results for its effectiveness.3-6 One possible reason to account for discordant findings is the definition and operationalization of the reablement model of health and social care. A new definition of reablement was recently published based on a Delphi process with 80% agreement for the final version.7 The new definition is:

Reablement is a person-centered, holistic approach that aims to enhance an individual's physical and/or other functioning, to increase or maintain their independence in meaningful activities of daily living at their place of residence and to reduce their need for long-term services. Reablement consists of multiple visits and is delivered by a trained and coordinated interdisciplinary team. The approach includes an initial comprehensive assessment followed by regular reassessments and the development of goal-oriented support plans. Reablement supports an individual to achieve their goals, if applicable, through participation in daily activities, home modifications and assistive devices as well as involvement of their social network. Reablement is an inclusive approach irrespective of age, capacity, diagnosis or setting. (p.11)7

To date, few studies discuss implementation factors for reablement,8-13 or focus on the term behavior change techniques (BCTs)14 or strategies used within studies.8,9,15-17 Michie and colleagues14 created a taxonomy of 93 BCTs (within 16 clusters) to identify the active ingredients within health (and other) interventions. Despite the call for more published information on interventions, such as using the Template for Intervention Description and Replication (TIDieR)18 checklist, many studies do not routinely report implementation (or behavior) strategies.19

Identifying implementation strategies in reablement which support positive health behaviors may assist research and practice. The new reablement definition7 offers some insights into BCTs. For example, the definition mentions the following possible BCTs: regular reassessments (from the taxonomy: 2.1 monitoring of behavior by others without feedback, 2.2 feedback on behavior, 2.5 monitoring of outcomes of behavior without feedback, and/or 2.7 feedback on outcomes of behavior), goal-oriented support plans [1.1 goal setting (behavior), 1.3 goal setting (outcome), and/or 1.4 action planning]; home modifications (12.1 restructuring the physical environment); and assistive devices (12.5 adding objects to the environment).7 This exercise illustrates the necessity to describe in detail the “active ingredients” of an intervention to (i) facilitate replication, and (ii) test in future which BCT or combination of BCTs are most effective in supporting and maintaining positive health behaviors.

In summary, reablement is a model of health and social care implemented in many global locations. Reablement, like rehabilitation, would benefit from a detailed description of the clinical service or research intervention for (i) the content and (ii) its implementation. We aim to start this process by identifying BCTs used in published reablement studies for people who are not living with significant cognitive impairment or dementia. We do not seek to look at the number of BCTs/study, rather which BCTs are reported within reablement services or research. These results may be used to describe and test which BCTs (alone or in combination) are most feasible, acceptable, and effective for people and settings.

MethodsWe conducted a scoping review and followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA)20 Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR)21 for conducting this synthesis. Below, we highlight the methods we used to identify and synthesize available evidence. As per the guidelines for scoping reviews, we aimed to provide an overview of the current evidence for reablement (across study designs) and did not conduct a formal assessment of study quality.22 Please note, we used nomenclature from the Cochrane Collaboration and define studies as the focus or unit of analysis while publications are the published report or manuscript.23 One study could have several publications.23

Protocol registration: We registered this scoping review with the (Joanna Briggs Institute, Australia)

Research Question: What behavior change techniques (BCTs) are included in peer-reviewed studies on reablement for people without significant cognitive impairment or dementia?

Eligibility criteria: We included publications with any study design focused on reablement, including all publication years and languages. We excluded publications not peer-reviewed, protocols, reviews, or studies focused on training staff to use reablement.24,25 We excluded studies on reablement for people living with dementia. We recognize the growing field of reablement for people with dementia,26 but wanted to narrow the focus of our findings.

Information sources and Search Strategy: We conducted the following database searches: (1) Cochrane Registry of Clinical Trials; (2) Embase; (3) MEDLINE (OVID); (4) selected EBSCO databases (APA PsycInfo, CINAHL Complete, SPORTDiscus); and (5) a focused title search in Google Scholar (allintitle: reablement or re-ablement). The last search was completed on April 8, 2021. As reablement is a relatively new term in the health literature, we only used the keywords “reablement” or “re-ablement” across all databases. We used the following concepts to define our search strategy: population: people without significant cognitive impairment or dementia receiving reablement; intervention: reablement; comparator: usual care, wait list control, other, no control group; and outcomes: behavior change techniques (BCT) based on the BCT Taxonomy.14

Data abstraction: Two authors (FA, MA) abstracted data for each study; a third author (MCA) checked data presented in Table 1. We extracted the following data for each study: location, first author, duration of reablement, number of sessions, and quote from study of most frequently reported BCT.

The table is a summary of 21 studies of reablement in community dwelling adults and older adults. The last column contains quotes from studies for goal setting, the most frequently reported behavior change technique (BCT).

| Location Publications | Study | Duration of Reablementa | Frequency orNumber of Sessionsa | Goal Setting Quote |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Australia | Lewin et al.28,29 | 8 or 12 weeks (maximum)28 | 3 sessions (minimum)28 | “It is goal-oriented and promotes active engagement in daily living activities using task analysis and redesign, work simplification, and assistive technology.” (p. 1275)28 |

| Denmark | Bødker et al.10,30,31 | 8 weeks30,31 | 1–3 sessions/week31 | “…to set up specific goals for each reablement program in collaboration with the reablement recipient. This is done at the end of the assessment meeting by the assessor or therapist using the Patient Specific Functional Scale (PSFS)”. (p. 13)10 |

| Denmark | Winkel et al.32 | 12 weeks | 3 sessions/week | “The role of the occupational therapist was to further specify ADL task performance problems of relevance to the participant, set goals and plan and adjust interventions during the program.” (p. 1348)32 |

| Norway | Birkeland et al.33,34Langeland et al.45Tuntland et al.50,51 | 5.7 weeks (mean)4–6 weeks (range)45 | 48% participants received 5 sessions/week33% participants received 3–4 sessions/week45 | “During the COPM assessment, the participant defined up to five activity goals that were essential to her or him. Based on these goals, a rehabilitation plan was developed to promote a match between the activities and goals identified by participants, and professional initiatives.” (p. 2)45 |

| Norway | Eliassen et al.35,-38 | Not reported | Not reported | “This was often defined in a reablement plan, which was based on the PT's (or the PT in collaboration with other team members’) assessments and the user's goals....” (p. 514)37 |

| Norway | Jakobsen et al.16,17Liaaen and Vik46 | 4 to 6 weeks16 | 5 sessions/week (maximum)16 | “Interestingly, having the goals of the older person in mind helped the health professionals become more aware of the need for change in how they worked.” (p. 4)46 |

| Norway | Jokstad et al.42,43 | 6 weeks43 | 7 sessions/week42 | “The participants related that some users mentioned concrete goals during the initial professional–user meeting.” (p. 911)42 |

| Norway | Hjelle et al.11,39-41Kjerstad and Tuntland44Tuntland et al.49 | 10 weeks (mean)493 months (maximum)41 | 7 (5) sessions/week(Mean, SD)49 | “Further, as part of the baseline assessment, the occupational therapist and physical therapist used the instrument Canadian Occupational Performance Measure (COPM) to identify activity limitations perceived as important by the participant…” (p. 3)44 |

| Norway | Magne and Vik47 | Up to 5 weeks reported | Not reported | “The older adults are in charge of setting goals focusing on their wish for participation in daily activities and how to regain and gain skills to achieve these goals.” (p. 2)47 |

| Norway | Moe and Brinchmann12,13 | 6 weeks (mean)13 | Daily sessions13 | “Exercises and other therapeutic activities are based on a detailed screening that identifies activity goals and functional impairments.” (p. 30)13 |

| Norway | Ranner and Vik48 | Not reported | Not reported | “For example, they first discussed how the service recipients could set goals and make decisions for themselves, but then they described how they made decisions for the service recipients.” (p. 6)48 |

| Sweden | Gustafsson et al.52,53Östlund et al.54 | 3 months53 | Not reported | “The intervention was a goal-directed, homebased, time-limited (three months) reablement, organized by an interprofessional team in which the controls received traditional homecare.” (p. 2)53 |

| Sweden | Zingmark et al.55,56 | 15 weeks (maximum)56 | Up to10 sessions+56 | “The focus for occupational therapy and physical therapy assessment, goalsetting…” (p. 1015)56 |

| Taiwan | Chiang et al.57 | 3 months | Not reported | “The care attendants needed to work with the family caregivers to identify the most needed care items through communication, set care goals together....” (p. 6)57 |

| Taiwan | Han et al.58 | 6 weeks | 1 session/week | “In the first week, the occupational therapist who administered the home program confirmed the 2–3 ADL tasks that patients perceived as important, realized the difficulties in performing those ADL tasks, and affirmed the level of improvement that patients wanted to achieve.” (p. 2)58 |

| Taiwan | Huang and Yang15 | Not reported | Not reported | Did not mention goal setting |

| United Kingdom | Beresford et al.8,9 | 6 weeks (maximum)3.9 weeks (mean)8 | 12 sessions/week, 7 (mean, SD)8 | “Of the services using personalised goals (n = 118), 92% said that they always set the goals in partnership with the user, and this was done before reablement started (49%) or soon after (42%). (p. 19)9 |

| United Kingdom | Champion59 | 6 weeks (maximum) | Telephone follow-up once/week | Did not mention goal setting |

| United Kingdom | Glendinning and Newbronner60 | 6 weeks, option for extension | Not reported | “Typically, initial assessments identify goals that users wish to achieve – these might relate to personal care, daily living tasks or social activities…” (p. 33)60 |

| United Kingdom | Slater and Hasson61 | Not reported | Not reported | Did not mention goal setting |

| United Kingdom | Whitehead et al.62 | 56 days (median)20–126 days (range) | 5 sessions (median)2–13 sessions (range) | “Each visit was categorised (in 5-minute intervals) into time spent on the following activities, listed as key intervention components in the published protocol: assessment, goal-setting, goal reviewing….” (p. 536)62 |

Coding BCTs: The taxonomy of 93 BCTs is divided into 16 clusters or groups. Each of the clusters contain related individual behavior strategies used within interventions or studies.14 Each BCT is represented by a number, e.g., 1.1 denotes that the BCT belongs to the first cluster and is the first technique in its group. Two authors (FA, MCA) adjudicated BCTs in an iterative process. They independently reviewed publications, then met over several sessions to discuss and confirm the list. The authors used NVivo (QSR International Pty Ltd, Melbourne, Australia) to identify and code BCTs in the selected publications. In addition, they searched keywords related to each BCT using the “Text Search Query” feature and allowed the program to search for synonyms of the keywords. Both authors reviewed the online BCT Taxonomy Training in advance of the adjudication process.27 At the end of the adjudication process, one author (MCA) reviewed the final list of BCTs, and a second author (PB), who also completed the BCT Taxonomy Training, checked each BCT with publications to confirm findings.

Synthesis of results: We used a narrative approach for the review, and present summary information for reablement studies in Table 1. We tabulated the frequency of BCTs and BCT clusters for each study in Tables 2 and 3.

This table presents the frequency of the behavior change techniques within clusters. Clusters are sorted by most to least frequent. We identified 11 of 16 possible behavior change technique clusters within included reablement studies.

This table reports the frequency of behavior change techniques (BCTs) identified within the included publications. The BCTs are sorted by frequency (most to least). We identified 27 out of 93 possible BCTs. Goal setting was reported in 18/21 studies.

Review team composition and experience: Our team consisted of trainees, researchers, and clinicians from various backgrounds, such as biomedical engineering, exercise science, health psychology, health sciences, medicine, occupational therapy, and physical therapy. Members of the team have significant experience conducting different types of knowledge synthesis (e.g., scoping, systematic, and umbrella reviews).

Quality assessment/Risk of bias: As per scoping reviews in general,22 we did not conduct a formal risk of bias or quality assessment of studies as the focus of the scoping review was to identify BCTs within published literature. However, two authors (FA, MCA) initially coded BCTs in each study independently to minimize bias. Discrepancies in coding BCTs were resolved with discussion. At the end of BCT adjudication, a different author (PB) reviewed each BCT and source justification within publications. Further, another author (SG) checked data in Table 1. None of the included studies were authored by any members of this scoping review team.

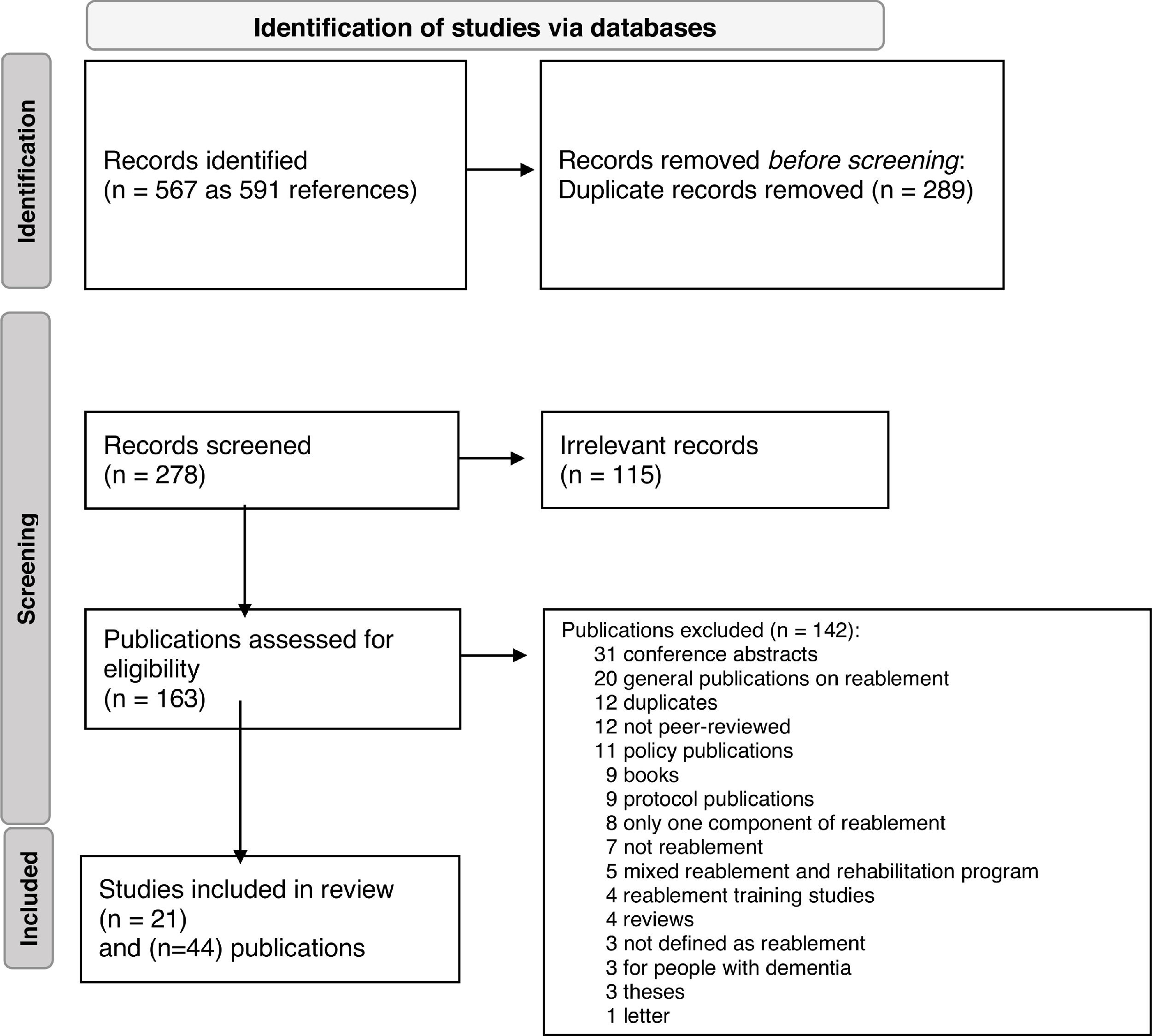

ResultsWe identified 567 studies (591 publications) and included 21 studies from 44 publications (PRISMA 2020 Flow diagram20 in Fig. 1). Publications were from Australia (two publications and one study; 5% of studies28,29), Denmark (four publications and two studies; 10% of studies10,30-32), Norway (24 publications and eight studies; 38% of studies11-13,16,17,33-51), Sweden (five publications and two studies; 10% of studies52-56), Taiwan (three publications and three studies; 14% of studies15,57,58), and United Kingdom (six publications and five studies; 24% of studies8,9,59-62). Table 1 provides a summary of the included studies by location and description of the reablement service. In all studies except one,15 the mean age of people receiving reablement was 60 years and older.

Behavior change techniques: We identified BCTs from 11 of 16 possible clusters (or groups) of individual strategies from the BCT Taxonomy.14 Items from six clusters appeared in over half of the studies, including (most to least frequent): goals and planning; social support; antecedents; feedback and monitoring; shaping knowledge; and repetition and substitution (Table 2).

We also identified 27 of the possible 93 BCTs. The following BCTs appeared in more than half of the studies (most to least frequent): 1.1 goal setting (behavior); 3.1 social support (unspecified); 4.1 instruction on how to perform a behavior; and 12.5 instruction on how to perform a behavior (Table 3). Goal setting (behavior) appeared in 18/21 (86%) studies (Table 1). Table 1 also provides direct quotes from published studies for goal setting, when reported. Within studies, there were reports of using a standardized instrument for goal setting: Canadian Occupational Performance Measure [COPM63]36,43,44,50,56,58 and the Patient Specific Functional Scale [PSFS64].10

DiscussionFor health care delivery, especially with complex interventions, it is important to understand components of the clinical service and how it was implemented for consistency of care, and to develop methods for expansion of innovative and effective services. Part of describing implementation is to clarify strategies for its delivery and adoption. Reablement is a complex health and social intervention involving multiple stakeholders such as adults and older adults, family members, and healthcare providers. In this scoping review, using the published taxonomy,14 we identified 27 BCTs across 11 clusters. These results extend a previous systematic review within physical therapy-led physical activity interventions, whereby only a third of a possible 93 BCTs were reported.65 We observed goal setting (behavior) and goals and planning were the most frequent BCT and cluster, respectively. Studies often cited goal setting as an integral component of reablement8-11,16,17,28-45,49-54,60,62 and it is contained within the new definition of reablement.7 This scoping review also provides insight into other behavior change strategies targeted at the person/patient level, but most often delivered or implemented by the provider and/or caregiver. Thus, our exploratory work generates hypotheses for future studies to develop and test acceptable, feasible, and effective BCTs within reablement to support peoples’ autonomy and independence.

There are many psychological theories for health behavior change,66-69 each with distinct components or foci. Frequently, there is a discrepancy between forming intentions (motivation) to change behavior (goal setting) and taking actions to enact performance (goal pursuit/implementation). The Health Action Process Approach (HAPA)68,69 aims to address the intention – behavior gap using a two-stage model of motivational and volitional factors. Motivation includes factors such as self-efficacy, outcome expectancies, and risk perception related to a new behavior (predictors of goal setting). Volition (goal pursuit) or the “action phase” involves cognitive (self-regulatory), behavioral, and situational (support, barriers) components.68,69 Theories such as HAPA demonstrate the multitude of conscious psychosocial processes which influence behavior, and thus, how people may experience reablement. These processes (at the person, family, and provider level) should be considered during the design and delivery of reablement (i.e., map BCTs onto theoretical determinants of behavior change and the reablement service), to enable behavior change and minimize the gap between intention and behavior.

Goal setting was the most common BCT reported by studies. Intentions or goals set the stage for behavior change. Goals may enable people to return to what matters most to them. Despite their importance in rehabilitation,70 gaps remain for defining and implementing patients’ goals within the clinical setting. Based on an evaluation of clinical practice by physical therapists (but not specifically for reablement), goals identified were short-term, function-focused, and few went beyond goal setting to goal pursuit.71 Goal setting is important but not enough, as goal pursuit is a distinct process70 to encourage adoption and maintenance of behaviors. Goal pursuit BCTs facilitate or support the journey towards achieving the pre-determined goal through reviewing goals or projects, feedback and monitoring, adding objects to the environment (e.g., assistive devices), and/or social support. However, health behaviors and reablement are not usually discussed in the literature, even if BCTs are contained within studies and the new reablement definition.7

At present, we do not know the most effective BCTs for adoption of some health behaviors. For example, in younger adults several BCTs were associated with positive physical activity behavior,72 whereas results were mixed for older adults.73 In a meta-analysis, the following self-regulatory BCTs were associated with lower self-efficacy and lower physical activity behavior in older adults: goal setting (behavior), feedback on behavior, self-monitoring of behavior, social support, information about others’ behavior, and coping planning.73 The review authors posit several plausible explanations for these findings such as cognitive challenges,73,74 prioritizing the present over the future, changes in motivation,75 and lower levels of physical activity among older adults.73 For some older adults, the meaning or definition of “goals” can also be challenging,76 and the goal (or target behavior) can be unrealistic or daunting. Further, changing health behaviors and forming habits also take time. In a younger population (university students) the median time to forming a habit (e.g., behavior becoming automatic) was 66 days (range 18–254 days).77 Given the essential role of goals (and sustainable health behaviors) in reablement (and rehabilitation in general), it is important to discern effective BCTs for people in receipt of healthcare.

In this scoping review, we noted implementation details for reablement were missing in some instances, although, this observation may be because details were reported elsewhere (i.e., protocol papers). Similar to rehabilitation,78 studies frequently do not provide sufficient details for a variety of reasons (limited space for publishing details, reporting guidelines are relatively new, etc.). Using a tool such as the TIDieR18 checklist and guideline is an important addition to the growing field of reablement. Reporting of reablement content and implementation details can improve delivery and uptake of reablement and permit teams to learn from each other.

Strengths and limitations: This scoping review has several strengths. For example, we included a variety of methodological designs to increase the number of included studies. The number and diversity of studies from various locations provide a wide-ranging summary of reablement services or research. We also acknowledge possible limitations. For example, as per scoping review methods we did not conduct risk of bias or quality assessment, and only used information contained in publications to code BCTs. However, two authors independently and together read through each publication multiple times and implemented a systematic text search query on NVivo. In addition, one author reviewed all adjudicated BCTs, and a second author confirmed the final list. Nonetheless, there may be a difference (e.g., more clarifying information) between published information and reablement practice/research. Further, we only included studies whereby the authors defined the intervention as reablement. We recognize other studies may be considered reablement but did not state this in the publication, and therefore were not included in this scoping review. Finally, we did not include studies on reablement for people with dementia, an emergent field of study.26 Future studies should explore implementation factors for reablement at the population level to discern its differences and similarities depending on important contextual factors.

ConclusionImplications for physical therapy practice: With this work we aim to start the conversation and develop a future research agenda for developing and testing BCTs most effective (within reablement or rehabilitation) for promoting positive health behaviors, and thus encouraging older adults’ autonomy and independence. We further highlight the need to report more details related to implementation of reablement for clarity and future replication. Beyond the scope of our work, we also generate research questions for how models of behavior change, and implementation science align with other rehabilitation perspectives. For example, the model of human occupation explores the choice of meaningful activities and occupation, and the interaction between volition, habituation, and performance79 which aligns well with the reablement model of care.

We gratefully acknowledge the support of the Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research, and Canada Research Chairs program for career awards for Prof Ashe and Prof Hoppmann.