Language is a barrier to implementing research evidence into practice. Whilst the majority of the world’s population speak languages other than English, English has become the dominant language of publication for research in healthcare.

ObjectiveThe aim of this study was to quantify the usage of the Physiotherapy Evidence Database (PEDro) web-site (www.pedro.org.au) and training videos by language, including the use of online translation, and to calculate relative usage of the different sections of the web-site.

MethodsGoogle Analytics was used to track usage of the PEDro web-site for July 2017 to June 2018. The number of views of each of the PEDro training videos was downloaded from YouTube for January 2015 to August 2018. The pageviews and videos were categorized by language and, for pageviews, web-site section.

Results2,828,422 pageviews were included in the analyses. The English-language sections had the largest number of pageviews (58.61%), followed by Portuguese (15.57%), and Spanish (12.02%). Users applied online translation tools to translate selected content of the PEDro web-site into 41 languages. The PEDro training videos had been viewed 78,150 times. The three most commonly viewed languages were English (58.80%), Portuguese (19.83%), and Spanish (6.13%).

ConclusionsThere was substantial use of some of the translated versions of the resources offered by PEDro. Future efforts could focus on region-specific promotion of the language resources that are underutilized in PEDro. The developers of PEDro and PEDro users can work collaboratively to facilitate uptake and translate resources into languages other than English to reduce the language barrier in using research to guide practice.

In the late twentieth century, English became the ‘lingua franca’ of science.1 Over 80% of peer-reviewed journals across all scientific disciplines in the SCOPUS database are written in English.1 Similarly, data from across all areas of healthcare indicate that 80–90% of articles are published in English. English also predominates in published physical therapy research. For example, the Physiotherapy Evidence Database (PEDro) identifies and indexes published articles reporting the results of trials, reviews and guidelines evaluating physical therapy interventions, regardless of the language of publication; yet approximately 90% of the content is published in English.2

The predominance of English in scientific publications means that proficiency in English enables researchers, clinicians and other users of research to capitalize on research findings to a greater extent. This may explain why a global survey found that a country’s English proficiency correlates with its level of innovation.3

The most recent data show that approximately 20% of the world’s working age population speaks English and less than 5% have English as their first language.4 An evaluation of global internet utilization reveals that English accounts for 25% of usage, followed by Chinese (19%), Spanish (8%), and Arabic (5%).5

Clinicians, policy makers, educators, and researchers may encounter difficulty in identifying and reading high-quality research if they are not able to access resources in their native language.6 Recent surveys of Brazilian physical therapists have found that whilst they are motivated to incorporate research into their clinical practice,7,8 the predominance of resources in English appears to be a barrier as resources in Portuguese are accessed preferentially.7 This language barrier could result in unnecessary duplication of research, as well as introducing bias into clinical decision-making.9

The mismatch between the proportion of articles published in English (80–90%) and the global proficiency in the English language (20–25%) points to the need for strategies to enable equitable access to research. Advances in machine learning capabilities have led to the development of online translation tools, but the accuracy of machine translations may be insufficient to support clinical decision-making. Whilst translations from Portuguese and German into English are reasonably accurate, machine translation from Hebrew, Japanese, Spanish, and Chinese into English are relatively poor.10 Translations from English into French, Italian, Swedish, and German have reasonable accuracy, whilst translation from English into Japanese, Persian, and Vietnamese rate particularly poorly.11 Translation issues include difficulty with finding equivalent vocabulary and working with an entirely different syntax, as well as difficulty displaying the language script.12 Translating sections of text out of context may fail to yield a reliable translation, which may be critical in understanding the research. Professional translation services would address these issues, but creates a financial barrier for researchers.13

To help reduce the language barrier to consuming research, providers of bibliographic databases have started using translation and multi-language strategies. For example, the Cumulative Index of Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) database allows users to search for articles using any of 24 different languages.14 Ovid Technologies provide natural language search interfaces in eight languages (English, French, German, Spanish, Simplified Chinese, Traditional Chinese, Japanese, Korean).15 PubMed is developing multilingual search engine interfaces,16 as well as allowing users to search for transliterated titles using English characters.17 The Cochrane Collaboration established its multi-language strategy in 2014, where the Cochrane Community provides human (and some machine) translation of Cochrane content into 15 languages, with 23,006 translations of abstracts and plain language summaries published by December 2017.18 Wikipedia, a highly utilized source of medical information online,19 includes content in 255 languages — the largest amount of medical content being in English, German, French, Spanish, Polish, Italian, Portuguese, Russian, Dutch, Japanese, Arabic, and Swedish.20 The PEDro evidence resource provides human translations of its web-site into 12 languages: English, Simplified Chinese, Traditional Chinese, French, German, Italian, Japanese, Korean, Spanish, Portuguese, Tamil, and Turkish.21 The training videos on the PEDro YouTube channel have also been translated into these languages except Turkish, but have also been translated into Dutch.

Evaluation of the impact and usage of multi-lingual evidence resources is required to guide their development and to optimize efforts to reduce the language barrier to using published research. An analysis of PubMed and Medline Plus in English and Spanish found higher use of the English versions in countries with greater English proficiency, and unsurprisingly, higher use of the Spanish platform in countries with greater Spanish proficiency.22 However, we have been unable to identify evaluations of healthcare databases by user language that are available in the public domain, other than the country of origin of the users of resources.23

The aim of this study was to quantify the usage of the PEDro web-site (www.pedro.org.au) and training videos by language. Use of online translation of web-site pages was also quantified. A secondary aim was to calculate relative usage of the different sections of the web-site to identify the most used elements that could be targeted in future translation efforts.

MethodsExtraction and processing of pageviewsGoogle Analytics was used to track usage of the PEDro web-site (www.pedro.org.au). The metric used in the evaluation was “pageviews,” or the number of times each universal resource locator (URL) was viewed by a user.24 The number of pageviews for each URL in the www.pedro.org.au domain for a 12-month period, from 1 July 2017 to 30 June 2018, were downloaded from Google Analytics. Two authors independently categorized the pageviews to confirm accurate classification; disagreements were resolved by discussion between the two authors.

Some URLs in the found set were invalid, so were excluded from the data set. These included paths containing error messages (contained the tag “404”), mistakes that would not take the user to a page (e.g., “/germann” instead of “/german”), or queries that would not take the user to a page (e.g., “/?s=low+back+pain”). Paths produced by the content management system when the web-site is being edited and paths for pages that were under construction or not publicly available were also excluded from the analysis because they represent administrative use rather than user pageviews.

URLs in the included data set were categorized by language (English, Simplified Chinese, Traditional Chinese, French, German, Italian, Japanese, Korean, Spanish, Portuguese, Tamil, Turkish) and web-site section (Home page, Frequently asked questions, Search help, Downloads, etc (for full list see Table 1)). The English and Portuguese web-sites contain sections for blog posts; pageviews for individual blog posts were clustered together for each language. The English web-site contains sections archiving trials judged to be the 15 most influential trials in physical therapy in 2014 and press releases. Pageviews for subsections for these sections were clustered together. The number of pageviews for each language and web-site section combination were tabulated.

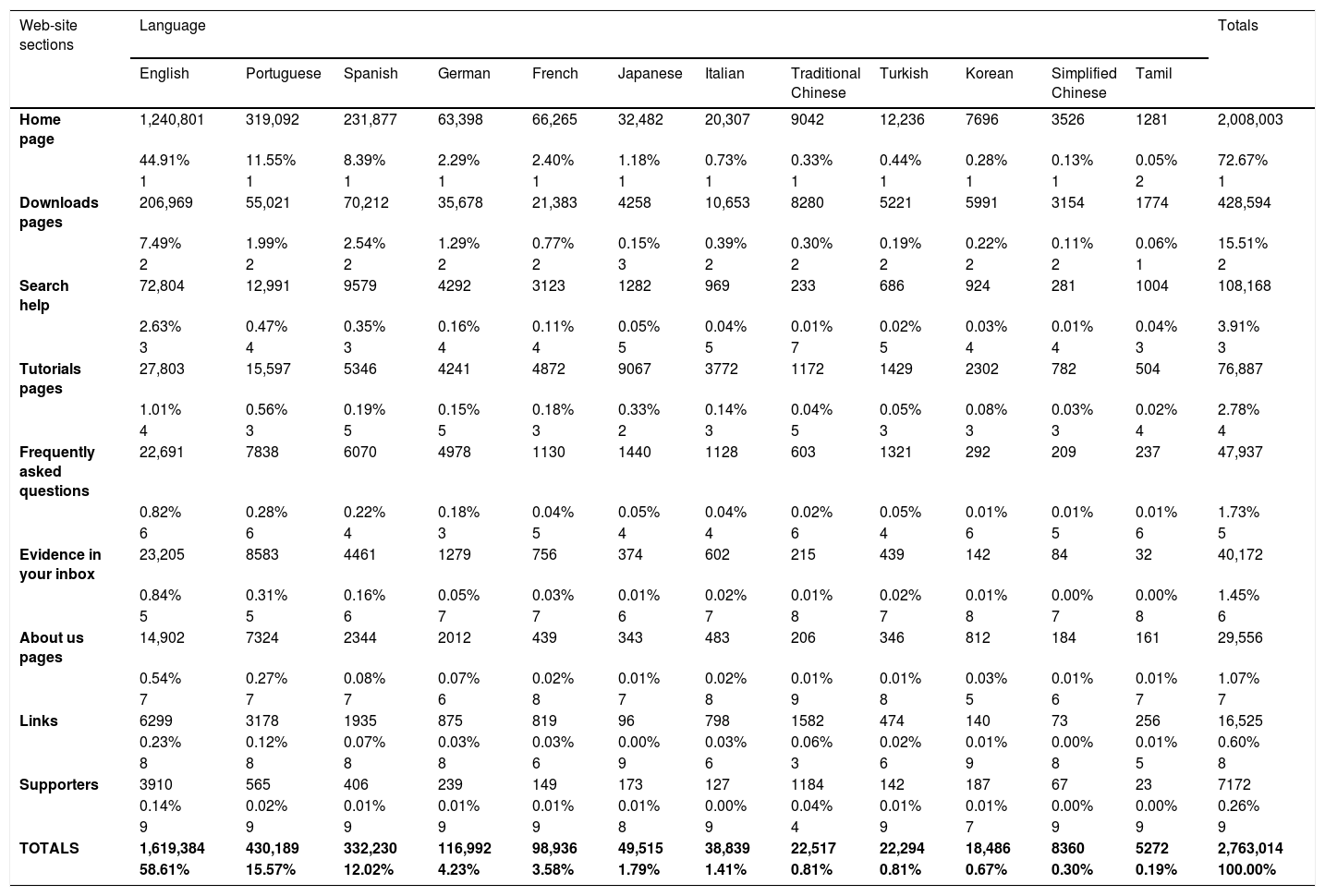

The number of pageviews for each section in the PEDro web-site that is available in all 12 languages. Language is in the columns, with data presented as number of pageviews, % of pageviews, and ranking for each web-site section. Web-site section is in the rows, and these are sorted by the total accesses for all languages (i.e., last column).

| Web-site sections | Language | Totals | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| English | Portuguese | Spanish | German | French | Japanese | Italian | Traditional Chinese | Turkish | Korean | Simplified Chinese | Tamil | ||

| Home page | 1,240,801 | 319,092 | 231,877 | 63,398 | 66,265 | 32,482 | 20,307 | 9042 | 12,236 | 7696 | 3526 | 1281 | 2,008,003 |

| 44.91% | 11.55% | 8.39% | 2.29% | 2.40% | 1.18% | 0.73% | 0.33% | 0.44% | 0.28% | 0.13% | 0.05% | 72.67% | |

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | |

| Downloads pages | 206,969 | 55,021 | 70,212 | 35,678 | 21,383 | 4258 | 10,653 | 8280 | 5221 | 5991 | 3154 | 1774 | 428,594 |

| 7.49% | 1.99% | 2.54% | 1.29% | 0.77% | 0.15% | 0.39% | 0.30% | 0.19% | 0.22% | 0.11% | 0.06% | 15.51% | |

| 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | |

| Search help | 72,804 | 12,991 | 9579 | 4292 | 3123 | 1282 | 969 | 233 | 686 | 924 | 281 | 1004 | 108,168 |

| 2.63% | 0.47% | 0.35% | 0.16% | 0.11% | 0.05% | 0.04% | 0.01% | 0.02% | 0.03% | 0.01% | 0.04% | 3.91% | |

| 3 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 7 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 3 | |

| Tutorials pages | 27,803 | 15,597 | 5346 | 4241 | 4872 | 9067 | 3772 | 1172 | 1429 | 2302 | 782 | 504 | 76,887 |

| 1.01% | 0.56% | 0.19% | 0.15% | 0.18% | 0.33% | 0.14% | 0.04% | 0.05% | 0.08% | 0.03% | 0.02% | 2.78% | |

| 4 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 5 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 4 | |

| Frequently asked questions | 22,691 | 7838 | 6070 | 4978 | 1130 | 1440 | 1128 | 603 | 1321 | 292 | 209 | 237 | 47,937 |

| 0.82% | 0.28% | 0.22% | 0.18% | 0.04% | 0.05% | 0.04% | 0.02% | 0.05% | 0.01% | 0.01% | 0.01% | 1.73% | |

| 6 | 6 | 4 | 3 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 6 | 4 | 6 | 5 | 6 | 5 | |

| Evidence in your inbox | 23,205 | 8583 | 4461 | 1279 | 756 | 374 | 602 | 215 | 439 | 142 | 84 | 32 | 40,172 |

| 0.84% | 0.31% | 0.16% | 0.05% | 0.03% | 0.01% | 0.02% | 0.01% | 0.02% | 0.01% | 0.00% | 0.00% | 1.45% | |

| 5 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 7 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 7 | 8 | 7 | 8 | 6 | |

| About us pages | 14,902 | 7324 | 2344 | 2012 | 439 | 343 | 483 | 206 | 346 | 812 | 184 | 161 | 29,556 |

| 0.54% | 0.27% | 0.08% | 0.07% | 0.02% | 0.01% | 0.02% | 0.01% | 0.01% | 0.03% | 0.01% | 0.01% | 1.07% | |

| 7 | 7 | 7 | 6 | 8 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 8 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 7 | |

| Links | 6299 | 3178 | 1935 | 875 | 819 | 96 | 798 | 1582 | 474 | 140 | 73 | 256 | 16,525 |

| 0.23% | 0.12% | 0.07% | 0.03% | 0.03% | 0.00% | 0.03% | 0.06% | 0.02% | 0.01% | 0.00% | 0.01% | 0.60% | |

| 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 6 | 9 | 6 | 3 | 6 | 9 | 8 | 5 | 8 | |

| Supporters | 3910 | 565 | 406 | 239 | 149 | 173 | 127 | 1184 | 142 | 187 | 67 | 23 | 7172 |

| 0.14% | 0.02% | 0.01% | 0.01% | 0.01% | 0.01% | 0.00% | 0.04% | 0.01% | 0.01% | 0.00% | 0.00% | 0.26% | |

| 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 8 | 9 | 4 | 9 | 7 | 9 | 9 | 9 | |

| TOTALS | 1,619,384 | 430,189 | 332,230 | 116,992 | 98,936 | 49,515 | 38,839 | 22,517 | 22,294 | 18,486 | 8360 | 5272 | 2,763,014 |

| 58.61% | 15.57% | 12.02% | 4.23% | 3.58% | 1.79% | 1.41% | 0.81% | 0.81% | 0.67% | 0.30% | 0.19% | 100.00% | |

Pages that were viewed using an online translation tool were analyzed separately. The two-letter International Organization of Standardization language code (i.e., ISO 639-2) in the translate code in the URL was converted into a language.25 It was presumed that URLs that were translated with the fanyi.youdao.com translation tool were translated into Chinese.26 These pageviews were clustered by the language the page was translated into. The total number of pageviews for each language was calculated.

Extraction and processing of views of training videosAll PEDro training videos are hosted on YouTube. The number of views of each video was downloaded for a 3.5-year period (inception (18 January 2015) to 27 August 2018) by one author. The videos were categorized by language (English, Simplified Chinese, Traditional Chinese, French, German, Italian, Japanese, Korean, Spanish, Portuguese, Tamil, Dutch) and the total views of each video in each language was tabulated.

AnalysisAll analyses were descriptive and were performed using Microsoft Excel. The number and proportion of pageviews for each language and each web-site section were computed and tabulated. The number and proportion of pageviews for each language used in online translation were calculated and tabulated. The number views of videos in each language were tabulated and expressed as a proportion of the total number of video views.

ResultsThe total pageviews for the www.pedro.org.au domain between 1 July 2017 and 30 June 2018 was 2,840,053. Of these, 11,631 (0.41%) pageviews were omitted from the analysis because they contained error messages (3860), mistakes that would not take the user to a page (3097), queries (2829), URL paths produced by the content management system (868), and paths for pages that were under construction (639) or not publicly available (338). The remaining pageviews were included in the analysis: 2,825,557 (99.49%) in the analyses of web-site sections and 2865 (0.10%) in the analyses of online translations. The training videos had been viewed 78,150 times between inception (i.e., 18 January 2015 for the channel, but the upload date for individual videos varies) and 27 August 2018.

The sections of the PEDro web-site that are available in all 12 languages had a total of 2,763,014 pageviews, see Table 1. Among these, the English-language sections had the largest number of pageviews (1,619,384 or 58.61%), followed by Portuguese (430,189 or 15.57%), Spanish (332,230 or 12.02%), German (116,992 or 4.23%), and French (98,936 or 3.58%). The language sections with the lowest usage were Tamil (5272 or 0.19%), Simplified Chinese (8360 or 0.30%), and Korean (18,486 or 0.67%).

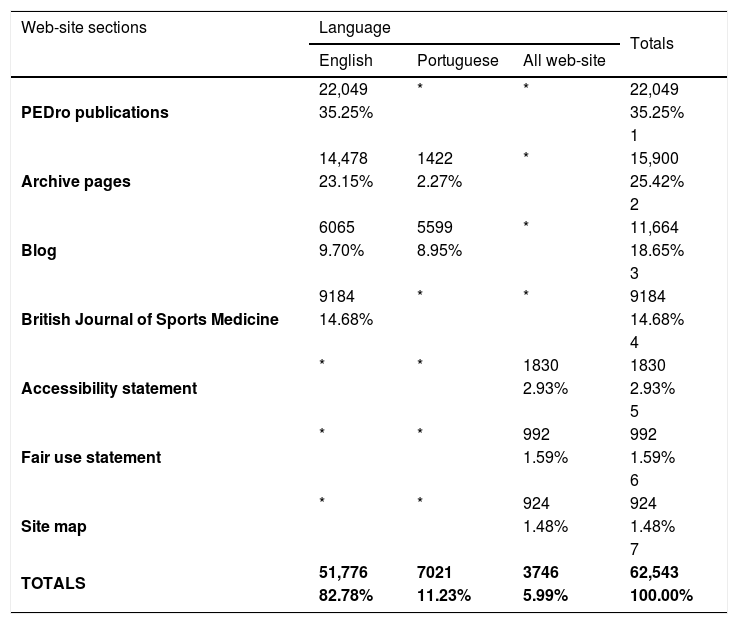

The sections of the PEDro web-site that are not available in all languages had a total of 62,543 pageviews, see Table 2. Among these, the English-language sections had the largest number of pageviews (51,776 or 82.78%), followed by Portuguese (7021 or 11.23%).

The number of pageviews for each section in the PEDro web-site that is not available in all 12 languages. Language is in the columns, with data presented as number of pageviews, % of pageviews, and ranking for each web-site section. Web-site section is in the rows, and these are sorted by the total accesses for all languages (i.e., last column).

| Web-site sections | Language | Totals | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| English | Portuguese | All web-site | ||

| PEDro publications | 22,049 | * | * | 22,049 |

| 35.25% | 35.25% | |||

| 1 | ||||

| Archive pages | 14,478 | 1422 | * | 15,900 |

| 23.15% | 2.27% | 25.42% | ||

| 2 | ||||

| Blog | 6065 | 5599 | * | 11,664 |

| 9.70% | 8.95% | 18.65% | ||

| 3 | ||||

| British Journal of Sports Medicine | 9184 | * | * | 9184 |

| 14.68% | 14.68% | |||

| 4 | ||||

| Accessibility statement | * | * | 1830 | 1830 |

| 2.93% | 2.93% | |||

| 5 | ||||

| Fair use statement | * | * | 992 | 992 |

| 1.59% | 1.59% | |||

| 6 | ||||

| Site map | * | * | 924 | 924 |

| 1.48% | 1.48% | |||

| 7 | ||||

| TOTALS | 51,776 | 7021 | 3746 | 62,543 |

| 82.78% | 11.23% | 5.99% | 100.00% | |

The web-site sections with the largest number of pageviews were the Home page (2,008,003 of 2,763,014, or 72.67%), Downloads pages (428,594 or 15.51%), Search help (108,168 or 3.91%), Tutorials pages (76,887 or 2.78%), and Frequently asked questions (47,937 or 1.73%), see Table 1. The web-site sections with the lowest number of pageviews were the Site map (924), Fair use statement (992), Accessibility statement (1830), and Supporters pages (7172), see Tables 1 and 2.

The pattern of usage of the web-site sections was relatively consistent across the different languages. The web-site sections that ranked in the top five for specific languages that were different from the overall pattern of usage were: Evidence in your inbox for English and Portuguese; Links for Traditional Chinese and Tamil; Supporters for Traditional Chinese; and About us for Korean.

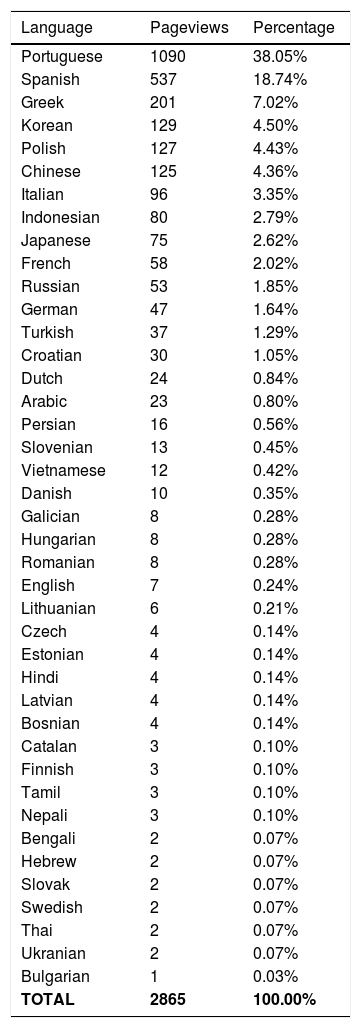

Users applied online translation tools to translate pages in the PEDro web-site into 41 languages, see Table 3. A total of 2865 pageviews were translated in this way. The five most common languages that the pages were translated into were Portuguese (1090 or 38.05%), Spanish (537 or 18.74%), Greek (201 or 7.02%), Korean (129 or 4.50%), and Polish (127 or 4.43%).

Number and percentage of languages that pageviews were translated into using an online translation tool.

| Language | Pageviews | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Portuguese | 1090 | 38.05% |

| Spanish | 537 | 18.74% |

| Greek | 201 | 7.02% |

| Korean | 129 | 4.50% |

| Polish | 127 | 4.43% |

| Chinese | 125 | 4.36% |

| Italian | 96 | 3.35% |

| Indonesian | 80 | 2.79% |

| Japanese | 75 | 2.62% |

| French | 58 | 2.02% |

| Russian | 53 | 1.85% |

| German | 47 | 1.64% |

| Turkish | 37 | 1.29% |

| Croatian | 30 | 1.05% |

| Dutch | 24 | 0.84% |

| Arabic | 23 | 0.80% |

| Persian | 16 | 0.56% |

| Slovenian | 13 | 0.45% |

| Vietnamese | 12 | 0.42% |

| Danish | 10 | 0.35% |

| Galician | 8 | 0.28% |

| Hungarian | 8 | 0.28% |

| Romanian | 8 | 0.28% |

| English | 7 | 0.24% |

| Lithuanian | 6 | 0.21% |

| Czech | 4 | 0.14% |

| Estonian | 4 | 0.14% |

| Hindi | 4 | 0.14% |

| Latvian | 4 | 0.14% |

| Bosnian | 4 | 0.14% |

| Catalan | 3 | 0.10% |

| Finnish | 3 | 0.10% |

| Tamil | 3 | 0.10% |

| Nepali | 3 | 0.10% |

| Bengali | 2 | 0.07% |

| Hebrew | 2 | 0.07% |

| Slovak | 2 | 0.07% |

| Swedish | 2 | 0.07% |

| Thai | 2 | 0.07% |

| Ukranian | 2 | 0.07% |

| Bulgarian | 1 | 0.03% |

| TOTAL | 2865 | 100.00% |

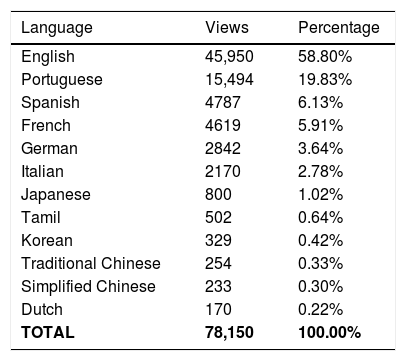

The PEDro training videos were viewed 78,150 times, see Table 4. Over half the PEDro training videos were viewed in English. The five most commonly viewed languages were English (45,950 or 58.80%), Portuguese (15,494 or 19.83%), Spanish (4787 or 6.13%), French (4619 or 5.91%), and German (2842 or 3.64%).

Number and percentage of views of the PEDro training videos by language.

| Language | Views | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| English | 45,950 | 58.80% |

| Portuguese | 15,494 | 19.83% |

| Spanish | 4787 | 6.13% |

| French | 4619 | 5.91% |

| German | 2842 | 3.64% |

| Italian | 2170 | 2.78% |

| Japanese | 800 | 1.02% |

| Tamil | 502 | 0.64% |

| Korean | 329 | 0.42% |

| Traditional Chinese | 254 | 0.33% |

| Simplified Chinese | 233 | 0.30% |

| Dutch | 170 | 0.22% |

| TOTAL | 78,150 | 100.00% |

This study achieved its aims of quantifying use of the various sections of the PEDro web-site by language, online translations of the web-site, and use of the training videos by language. The English-language sections of the PEDro web-site had the largest number of pageviews, followed by Portuguese, Spanish, German, and French. The language sections with the lowest usage were Tamil, Simplified Chinese, and Korean. Users applied online translation tools to translate pages in the PEDro web-site into 41 languages, the five most common being Portuguese, Spanish, Greek, Korean, and Polish. Regarding PEDro training videos, the five most commonly viewed languages were English, Portuguese, Spanish, French, and German.

The results of this study are credible because the data are likely to be representative of PEDro users’ normal activity because users were unaware that data on use of the web-site by language were being monitored during the study period. Furthermore, data were collected on a consecutive sample of users and >99% of the URLs were deemed relevant and subsequently analysed. The prevalence data are unlikely to be influenced by sampling error because of the large datasets: 2,825,557 pageviews, 2865 online translations, and 78,150 training videos. The large datasets also mean there is very little uncertainty in the prevalence estimates, for this reason we elected not to report 95% confidence intervals around the prevalence estimates. For example, the first result in Table 1 is that the English-language Home page accounted for 44.91% of the pageviews of each section in the PEDro web-site that is available in all 12 languages. The confidence interval barely departs from the main estimate: 44.85–44.97%. Even in the much smaller dataset of 2865 online translations, the confidence intervals remain very narrow. For example, the first result in Table 3 is that Portuguese accounted for 38.05% of online translations, with a confidence interval of 36.28–39.84%.

Usage of the non-English pages and videos was substantial (1,150,651 non-English pageviews in 1 year and 32,200 video views), which suggests that translation has reduced the language barrier for many users. An implication of this finding for database developers is that it is likely to be worth investing making their web-sites accessible in multiple languages, because such efforts can result in substantial usage of the translated content. Database developers could also compare a language analysis such as ours to the location of users (which can be easily monitored through Google Analytics). In this way, database developers could see where substantial usage is presumably occurring in a non-native language, and also where usage is low and might be improved if a translation were offered. For example, in 2018, users searched PEDro from 213 countries,21 equating to hundreds more languages than the 12 in which the PEDro web-site is currently available. This suggests that use of PEDro might increase with further translations. In particular, countries with usage in the top 20 but without a PEDro translation for their main language include Netherlands, and India. An implication for clinical physical therapists who do not have English as their first language is to consider using the translated web-pages because many other users are finding them helpful. For research or clinical physical therapists who are bilingual, they might consider assisting with translation of PEDro into an additional language. National physical therapy organizations might also consider assisting with translation of the web-site to increase the use of evidence by their members.

Although usage of the translated web-pages was substantial, it was also variable across the 12 languages, which generates further important implications. Speakers of some languages - particularly Portuguese and Spanish - are accessing PEDro in significantly higher proportions compared to overall usage. Some of this increased use can be explained by local promotion efforts of PEDro supporters in Brazil, as well as a social media presence (PEDrinho blog, Facebook and Twitter) in Portuguese. With other languages, usage is much lower than anticipated (particularly Simplified Chinese). This implies that some national physical therapy organizations and policymakers could collaborate with PEDro in promotion of this resource to encourage greater engagement with research evidence by local physical therapists. This finding also generates an implication for both research and clinical physical therapists in some countries to consider whether they are using evidence as much as their international peers.

Another implication from the study arises from its identification of which translated parts of the web-site were the most used, because this information could help target future translation efforts. The web-site sections with the largest number of pageviews were the Home page, Downloads pages (which includes the PEDro scale and a confidence interval calculator), Search help, Tutorials pages (which include: asking questions, critical appraisal, and applicability), and Frequently asked questions. The web-site sections with the lowest number of pageviews were the Site map, Fair use statement, Accessibility statement, and Supporters pages. Whilst the pattern of usage of the web-site sections was relatively consistent across different languages, some increased utilization was evident in particular sections with some languages. This information could be used by database developers to identify the most used elements that could be targeted in future translation efforts. There are also implications for clinical and research physical therapists here. By reading Tables 1 to 4, they may become newly aware of some resources available as part of the web-site. By observing the rates of usage for their language, they may recognize underuse of some of the resources on the web-site relative to their international peers, and therefore consider exploring these resources.

Online translations of various PEDro web-pages occurred in 41 languages, which reinforces the implication for physical therapists and physical therapy organizations to support further translation of the PEDro web-site into the languages listed in Table 3. Interestingly, included in the 41 languages were all 11 of the non-English languages into which the PEDro web-site has already been translated. While this may seem counter-intuitive, it is worth recognizing that the number of pageviews that underwent online translation in each of these 11 languages was less than 1% of the pageviews of translated content for that language. It is not possible to determine why some users chose to use online translation of the English pages rather than use the fully translated pages. Perhaps some users were unaware of the translated web-pages — but this seems unlikely given the prominence of the translation options on the Home page. Perhaps instead bilingual users who use the English-language pages of PEDro occasionally seek translation of an unfamiliar English word or phrase via online translation of the current page, rather than moving across to the fully translated pages. Reassuringly, >99% of the time, users accessing translated content are doing so using the existing translated pages, because they presumably provide more-faithful translations than automated online translation. An implication for new users of PEDro from non-English speaking backgrounds is that existing users overwhelming choose to use the formally translated web-pages so it is presumably a better option for content than online translation.

There was strong similarity in how the languages were ranked in prevalence of usage of translated web-pages (i.e., order of languages in Table 1) and usage of the PEDro training videos (i.e., order of languages in Table 4). A notable discrepancy is that there were very few views of the PEDro training videos in Traditional and Simplified Chinese. This is presumably because YouTube is inaccessible in mainland China due to implementation of a firewall.27 Provision of training videos on a platform easily accessible in China would be a helpful strategy.

We have been unable to identify similar studies analyzing the use of other healthcare-related databases by language. Further research is required across the wide range of available platforms to make informed decisions regarding development and translation of these resources. The information generated in this study can help to determine prioritization in development of further educational content and translation efforts.

A limitation of the study is that not all translated content had been in place for the same amount of time, because translations are published as funding becomes available. It may take time for awareness of the translated pages to spread among physical therapy communities and other users. However, even the most recent translation (Tamil) had already been in place for 2 years when the study was conducted, and the existence of each translation had been promoted by relevant national physical therapy organization(s). Importantly, this limitation does not invalidate the findings of the study, which accurately represent the current state of usage of PEDro by language.

Further work is needed to reduce barriers to access among specific language groups. The impact of promotional strategies for these groups needs to be assessed. Alternative platforms for access may also be a consideration.

ConclusionsThis study has demonstrated substantial use of translated versions of the resources offered by PEDro. Variations in usage of PEDro content by language suggest avenues for further translations and other changes to facilitate usage internationally. Implications for the developers of PEDro (or other resources), professional organizations, policymakers, and physical therapists in clinical or research roles include investing in translation into non-English languages, being aware of available translations, and the value of working collaboratively to reduce the language barrier.

FundingThis research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethics and study designEthics approval was not required as the project analyzed anonymous user data obtained from Google Analytics and YouTube. The STROBE checklist was utilised for reporting of this observational study.

Conflicts of interestThe authors are all involved in the production of the Physiotherapy Evidence Database (PEDro). AM is employed as the PEDro Research Officer and MRE, SJK and AMM sit on the Steering Committee for the PEDro Partnership. They have no other conflicts of interest to declare.

PEDro is funded by industry groups including the Australian Physiotherapy Association, Motor Accident Insurance Commission, Transport Accident Commission, Cerebral Palsy Alliance, Chartered Society of Physiotherapy, and over 40 other physiotherapy member organizations.