Over recent years there has been a paradigm shift towards a patient-centred biopsychosocial care model in physical therapy. This new paradigm features a growing interest in understanding the contextual factors that influence the patient's experience of disease, pain and recovery. This includes generalized consensus regarding the importance of establishing a therapeutic relationship that is centred on the patient.

ObjectiveTo explore physical therapists’ perceptions and experiences regarding barriers and facilitators of therapeutic patient-centred relationships in outpatient rehabilitation settings.

MethodsThis is a qualitative study with four focus groups including twenty-one physical therapists. Two researchers conducted the focus groups, using a topic guide with predetermined questions. The focus group discussions were audiotaped and videotaped, transcribed verbatim and analysed thematically using a modified grounded theory approach.

ResultsPhysical therapists perceived that the therapeutic patient-centred relationship not only depends on the personal qualities of the professional, but also on the patient's attitudes and the characteristics of the context, including the organization and team coordination.

ConclusionsAlthough being more linked towards the patients’ contextual factors and needs than towards the practice of the profession, a therapeutic relationship is worth considering by physical therapists. Furthermore this study highlights the need for physical therapists and administrators to rethink the situation and propose strategies for improvement.

Physical therapy is a profession that is fast adopting a biopsychosocial patient-centred approach.1 This model recognizes that social, psychological, cultural and contextual factors all influence individual experiences of illness and recovery.2 These contextual factors include elements of a patient's environment or behaviours that are relevant to their care, such as their economic situation, access to care, social support, and skills and abilities.3 The need to explore and treat pathology and what this represents to the individual, entails the establishment of a relationship of technical assistance that is centred on the person's needs,4 thus establishing a patient-centred health system.3 Under this new biopsychosocial paradigm, the relationship between health professionals and the recipients of care is one of the keys to therapeutic success.5 Indeed, there is a growing consensus that quality of care depends directly on the establishment of a therapeutic relation that is centred on the individual.6,7

A number of studies reveal a significant correlation between high quality therapeutic relationships and successful treatment results.8,9 Several reports have been published regarding health professionals’ perceptions on therapeutic patient-centred relationships. In this sense, Scanlon10 concludes that the therapeutic relationship is a combination of learning interpersonal skills, self-knowledge and personal maturity. Furthermore, Pinto et al.11 suggest that patient-centred interactions with emotional support that allow patient participation during the treatment process improve the therapeutic alliance. Nevertheless, very few studies are focused specifically on physical therapy professionals.12,13 One of the studies available is a review and meta-analysis carried out by O’Keeffe et al.14 on the perceptions of physical therapists and patients regarding the factors that influence their interactions. This review included 13 studies, of which only 3 examined the perceptions of physical therapists, concluding that the key to successful interactions is the physical therapists’ practical, communication and interpersonal skills, providing individualized care, as well as organizational and environmental factors. As a result, we have identified a gap in the available literature concerning physical therapists’ experiences and their perceptions on this topic. The aim of our study was to explore physical therapists’ perceptions and experiences regarding the barriers and facilitators of therapeutic patient-centred relationships in outpatient rehabilitation settings.

MethodsDesignA qualitative study was conducted using focus group techniques.

Setting and participantsThe inclusion criteria consisted of physical therapists from public health centres of the Community of Valencia (Spain) with a minimal experience of one year at the same workplace, working a minimum of 30h/week.15

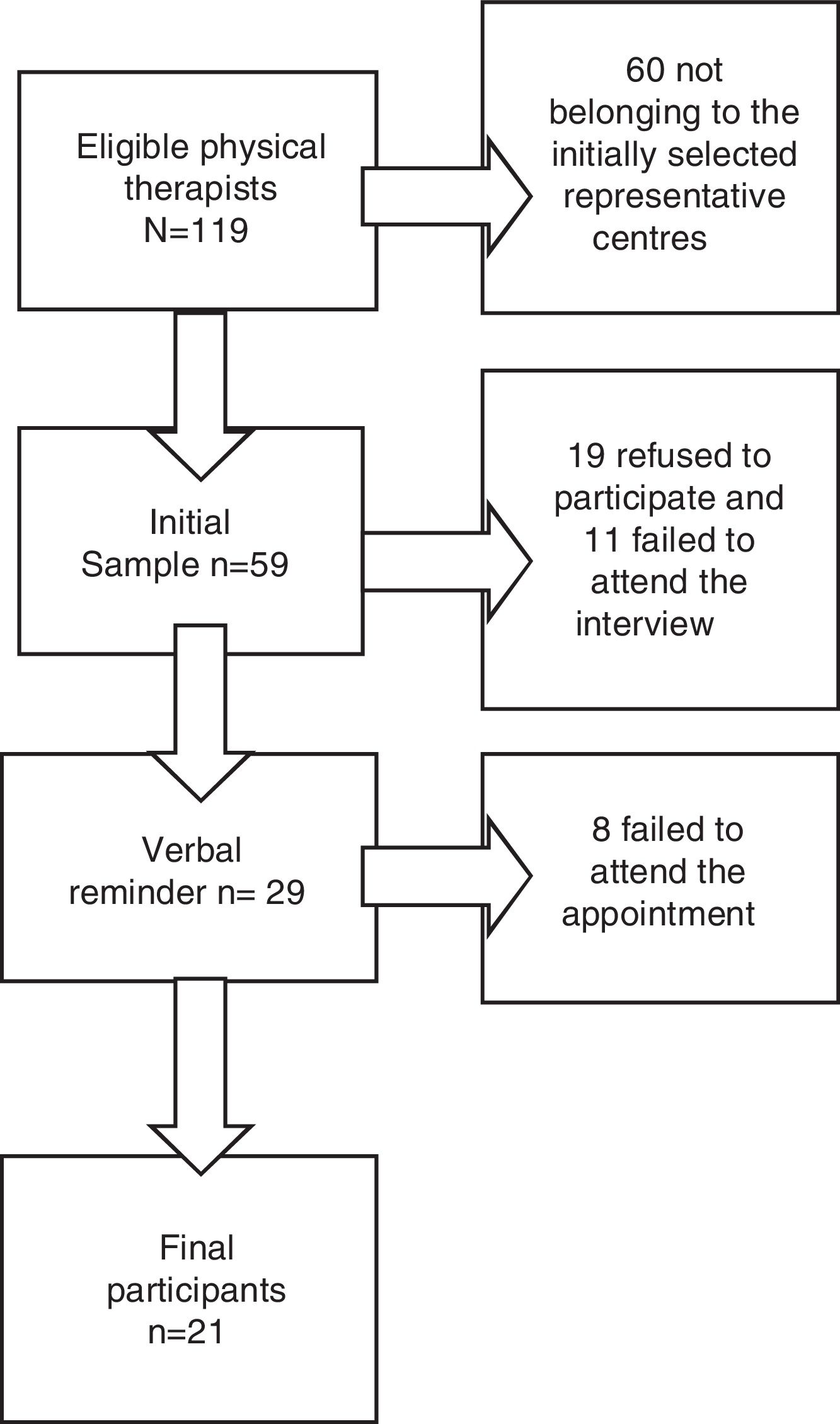

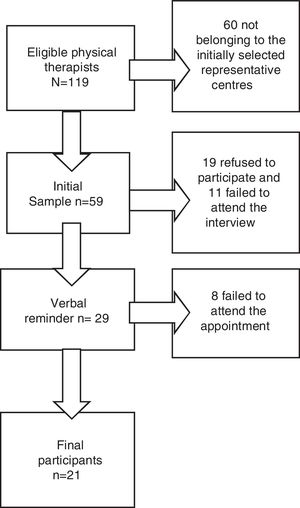

Recruitment119 physical therapists fulfilled the inclusion criteria. Participants were recruited from six hospitals, eleven health clinics and one public nursing home. These centres were intentionally selected because they represented the heterogeneity of profiles that we needed to organize the groups. Purposive sampling was used to include professionals working in rural or urban areas, in primary or specialized care, and with different types of patients in order to generate richer findings. Eventually, an initial sample of 59 physical therapists was used for the study. The 60 remaining physical therapists were saved as a ‘back-up’ to be used if necessary (lack of data saturation, sick leave among the physical therapists of the selected centres, etc.) since they worked at a group of centres that represented the heterogeneity necessary for the study. The recruitment process took place between May and October 2015. The stages of selection for the focus groups are shown in Fig. 1.

At each centre, a member of the research team met with the physical therapists concerned who explained the project and requested their voluntary participation in the study. Potential candidates were given an explanatory letter regarding the objectives of the meeting, the date, and the location of the same. One week before the meeting, the prospective participants were contacted by telephone to determine their willingness to participate, then, again, one day before the focus group meeting, as a reminder of the date and time and to confirm their assistance.

EthicsThe study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the University Cardenal Herrera CEU, and the Research Ethics Committees of the Provincial Hospital of Valencia, the Elche University Hospital and Vinalopó University Hospital. All participants accepted to being interviewed prior to the beginning of each session and signed the informed consent

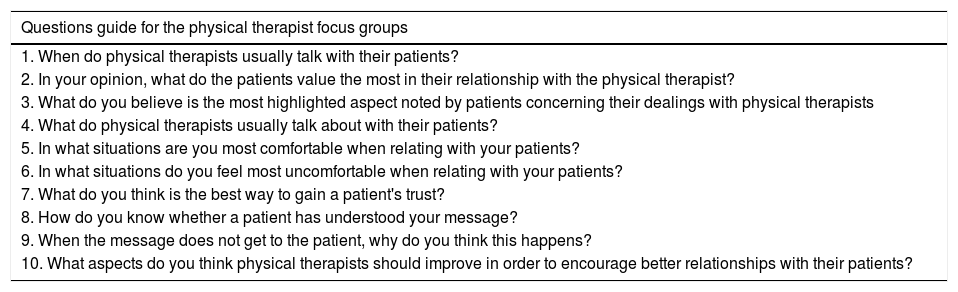

Data collectionAll the focus groups were conducted by a moderator (ORN), and an assistant (JMB) A topic guide with predetermined questions was used (Table 1). This was created based on a literature review, and modified after the performance of a pilot test with five physical therapists sharing similar characteristics to those participating in the focus groups. Group discussions were audio- and videotaped.

Thematic guide for focus group discussions.

| Questions guide for the physical therapist focus groups |

|---|

| 1. When do physical therapists usually talk with their patients? |

| 2. In your opinion, what do the patients value the most in their relationship with the physical therapist? |

| 3. What do you believe is the most highlighted aspect noted by patients concerning their dealings with physical therapists |

| 4. What do physical therapists usually talk about with their patients? |

| 5. In what situations are you most comfortable when relating with your patients? |

| 6. In what situations do you feel most uncomfortable when relating with your patients? |

| 7. What do you think is the best way to gain a patient's trust? |

| 8. How do you know whether a patient has understood your message? |

| 9. When the message does not get to the patient, why do you think this happens? |

| 10. What aspects do you think physical therapists should improve in order to encourage better relationships with their patients? |

At the beginning of each session, participants were provided an explanation of the study objective, and they were informed of how the extracted information would be used. Focus groups were conducted until data saturation was achieved. Sessions lasted an average of one and a half hours.

The sessions were transcribed verbatim. Notes taken during the interviews and the moderator's reflections were used to elaborate a report for each group conducted.

AnalysisTranscribed sessions were used for independent analysis. Participants’ names were changed using an assigned numeric code for both the transcripts and quotations. A modified grounded theory approach was used for data analysis.16 The grounded theory methodology allows the generation of theory from data obtained through qualitative studies. The adaptation of grounded theory used in this study incorporated the process of data collection, and its coding and analysis, using a process of constant comparison, but without the component of developing a theory in the light of results.5 Three authors (ORN, JMB, MLC) reviewed the transcripts independently and coded sentences that contained meaningful incidents. These were labelled in categories using a combination of predetermined and emergent codes. These three authors reviewed and compared their findings in order to reach an agreement on codes and categories. Three rounds of coding and discussion took place with the aim of enhancing the credibility of the coding process and to develop clearer categories. This process was iterative with data collection from subsequent transcripts, and was considered completed when a decision was made based on the consensus that data saturation had been met. The next level of analysis involved identifying relationships between categories and the grouping of categories with hierarchical conceptual uniformity into themes and subthemes. To check the consistency of the final themes and subthemes, two researchers (FMM, JMBR) cross-checked their agreement based on a blind review using codes for the same passages of two transcripts.17 Any disagreements between the two researchers were resolved by discussion. At every step, an independent author (MCMG) played the role of reviewer to verify if the analysis was systematically supported by the data, thus enhancing dependability.

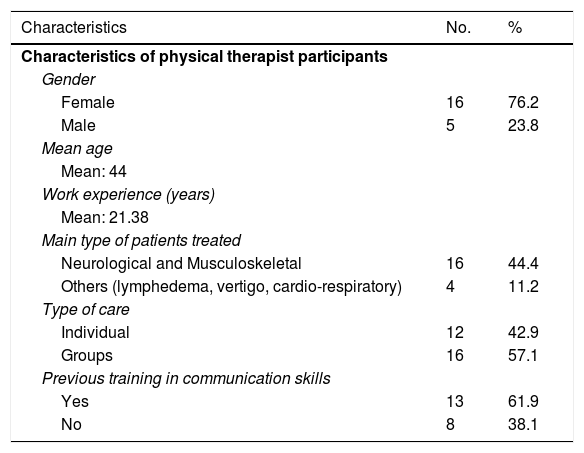

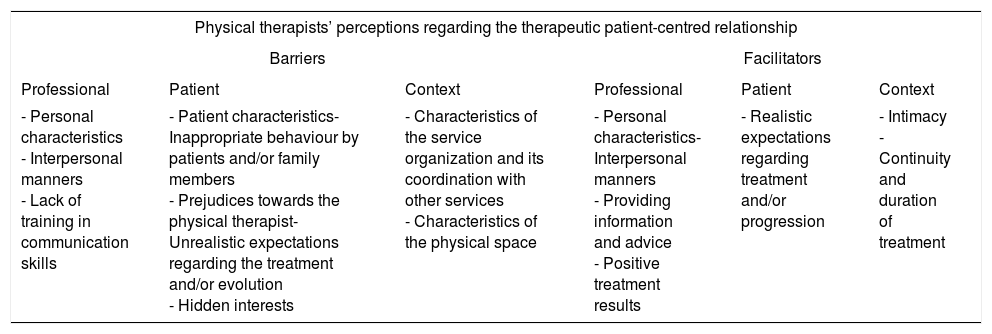

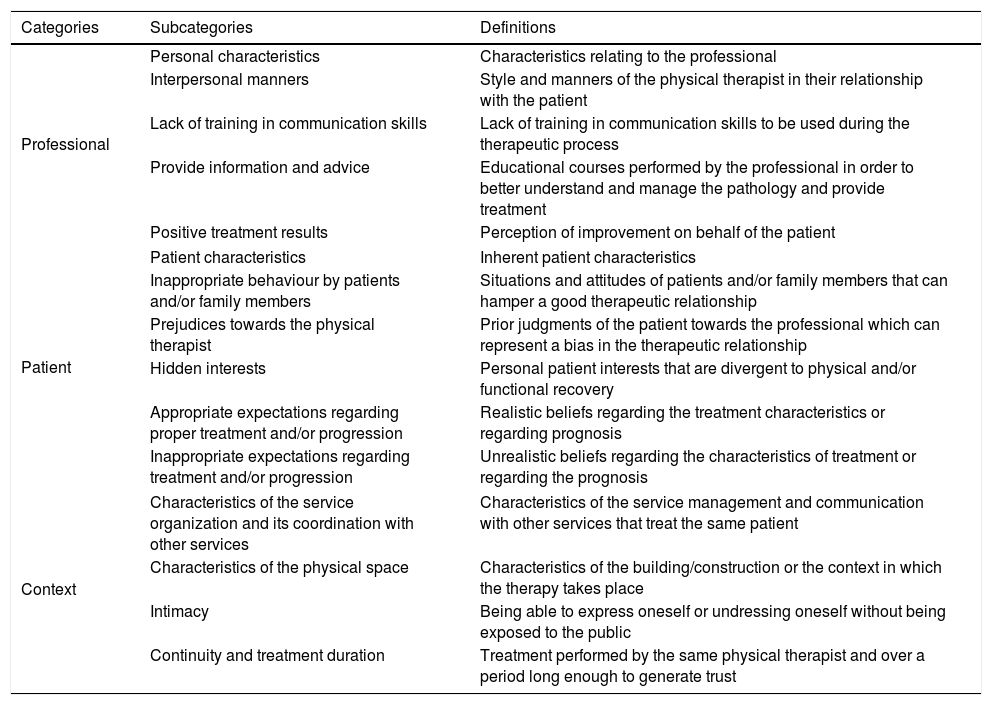

ResultsData saturation occurred after four focus groups; the final group did not contribute any new themes or categories. Focus group sizes varied from five to six participants. A total of 21 physical therapists participated in these focus groups. Characteristics of physical therapists are shown in Table 2. Physical therapists’ experiences and perceptions were related to one of the following themes: (1) relationship barriers; and (2) relationship facilitators, as shown in Table 3. Table 4 displays categories and subcategories of barriers and facilitators and their definitions. These are presented according to the resulting subthemes, accompanied by quotes extracted from the focus groups.

Characteristics of the physical therapist participants.

| Characteristics | No. | % |

|---|---|---|

| Characteristics of physical therapist participants | ||

| Gender | ||

| Female | 16 | 76.2 |

| Male | 5 | 23.8 |

| Mean age | ||

| Mean: 44 | ||

| Work experience (years) | ||

| Mean: 21.38 | ||

| Main type of patients treated | ||

| Neurological and Musculoskeletal | 16 | 44.4 |

| Others (lymphedema, vertigo, cardio-respiratory) | 4 | 11.2 |

| Type of care | ||

| Individual | 12 | 42.9 |

| Groups | 16 | 57.1 |

| Previous training in communication skills | ||

| Yes | 13 | 61.9 |

| No | 8 | 38.1 |

Map of themes, subthemes and categories according to the perceptions and experiences expressed in the physical therapy focus groups.

| Physical therapists’ perceptions regarding the therapeutic patient-centred relationship | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Barriers | Facilitators | ||||

| Professional | Patient | Context | Professional | Patient | Context |

| - Personal characteristics - Interpersonal manners - Lack of training in communication skills | - Patient characteristics- Inappropriate behaviour by patients and/or family members - Prejudices towards the physical therapist- Unrealistic expectations regarding the treatment and/or evolution - Hidden interests | - Characteristics of the service organization and its coordination with other services - Characteristics of the physical space | - Personal characteristics- Interpersonal manners - Providing information and advice - Positive treatment results | - Realistic expectations regarding treatment and/or progression | - Intimacy - Continuity and duration of treatment |

Categories and subcategories of barriers and facilitators and their definitions.

| Categories | Subcategories | Definitions |

|---|---|---|

| Professional | Personal characteristics | Characteristics relating to the professional |

| Interpersonal manners | Style and manners of the physical therapist in their relationship with the patient | |

| Lack of training in communication skills | Lack of training in communication skills to be used during the therapeutic process | |

| Provide information and advice | Educational courses performed by the professional in order to better understand and manage the pathology and provide treatment | |

| Positive treatment results | Perception of improvement on behalf of the patient | |

| Patient | Patient characteristics | Inherent patient characteristics |

| Inappropriate behaviour by patients and/or family members | Situations and attitudes of patients and/or family members that can hamper a good therapeutic relationship | |

| Prejudices towards the physical therapist | Prior judgments of the patient towards the professional which can represent a bias in the therapeutic relationship | |

| Hidden interests | Personal patient interests that are divergent to physical and/or functional recovery | |

| Appropriate expectations regarding proper treatment and/or progression | Realistic beliefs regarding the treatment characteristics or regarding prognosis | |

| Inappropriate expectations regarding treatment and/or progression | Unrealistic beliefs regarding the characteristics of treatment or regarding the prognosis | |

| Context | Characteristics of the service organization and its coordination with other services | Characteristics of the service management and communication with other services that treat the same patient |

| Characteristics of the physical space | Characteristics of the building/construction or the context in which the therapy takes place | |

| Intimacy | Being able to express oneself or undressing oneself without being exposed to the public | |

| Continuity and treatment duration | Treatment performed by the same physical therapist and over a period long enough to generate trust | |

Personal characteristics such as age (believing that youth is perceived as having a lack of experience) or aspects such as poor physical or emotional status, which hinders social relations, were identified by the physical therapists in this study as barriers. “When you’re not feeling well…you don’t feel like talking nor do you feel like being spoken to… but you have to try; I do” (Female, 44 years, work experience: 22 years.)

Interpersonal manners were viewed by participants as important, this is the way the professional relates with the patient and includes listening and respecting the patient, excessive trust, being overly familiar and not performing individualized treatments. “…there is over-familiarity…. We still don’t have the professionality of what should be the proper way to treat a patient… and we don’t know what our place is” (Male, 48 years, work experience: 25 years).

Lack of training in communication skills also emerged from the focus groups, with participants valuing skills such as assertiveness and knowing how to communicate bad news. “…in the field of physical therapy in general… we don’t know to stand our ground, establishing limits, ‘this will be done like so and you have to do it like this always, and you should always do it, and in front of me you shall do this, and I will do this and that, and that's all there is to it’, we don’t know how to do this” [speaking about assertiveness] (Male, 48 years, work experience: 25 years).

Certain patient characteristics were mentioned by participants, such as dependent personalities, which demand a more professional and personal care. Furthermore, participants identified the effects of low perceptions of self-efficacy, as these make learning more cumbersome as well as affecting the ability to acquire new knowledge: “There are many [patients] who, at the very beginning, while you are explaining an exercise say: ‘ah, I am a real klutz at this exercise, I am never going to learn it, I won’t do it”’ (Female, 44 years, work experience: 21 years).

Inappropriate behaviour by patients and/or family members were also a source of concern for physical therapists, including white lies, or incidences involving the creation of alliances between the family and the professional in order to hide information from the patient. Also, participants spoke of the negative effects that arose from a lack of motivation: “It is truly uncomfortable because, I don’t know, people don’t want you to discharge them and they don’t work, they don’t do anything, not a thing, because they don’t want to and they aren’t motivated” (Female, 28 years, work experience: 5 years).

Prejudices towards the physical therapist were another subtheme emerging from the focus groups. This hampers the development of trust in the physical therapist from the onset of the relationship. “…. It has happened to me with patients, I don’t know: [they think] ‘look at this hippy’, and so they have come with this prejudice and this already conditions them [from the onset]” (Female, 44 years, work experience: 22 years).

Inappropriate expectations regarding treatment and/or progression were another barrier identified and which can lead patients to think that the treatment has been ineffective. “…when patients who are not going to recover, such as neurological patients, who are going to have consequences, have expectations of the treatment and do not understand, however much I explain to them, or the doctor explains, as their expectations are not the same as ours” (Female, 28 years, work experience: 5 years)

The presence of hidden interests that have nothing to do with the improvement of functionality were also noted by the group: “this person can have another hidden intent which may perhaps be to get money out of here or there, or taking leave, seeking unemployment, from the insurance company, right? Things like that” (Male, 30 years, work experience: 7 years).

Characteristics of the service organization and its coordination with other services were also pointed out, such as the lack of team coordination, the excessive ratio of patients per physical therapist, the lack in the continuity of treatments. For example, regarding the lack of team coordination, one participant stated: “That is a situation of stress when communicating with the patient, that a physician may say something and we say the opposite” (male, 50 years, work experience: 26 years)

Also, characteristics of the physical space or, more concretely, the lack of intimacy: “Many times we do not have the appropriate space, because we have a lack of intimacy… [there are] lots of patients around, and sometimes you can’t tell the patient many things” (female, 46 years, work experience: 24 years).

Personal characteristics, the physical therapist's age provides a feeling of experience, as reported by the following physical therapist: “… I see that the patients, when they go to hospital and they are assigned the young girl, or the “Barbie” … and then, of course, they ask you, as you are the most senior…” (Female, 50 years, 12 years experience).

Interpersonal manners were valued by participants, including traits such as patience, kindness, a warm approach, confidence, accessibility, involvement, assertiveness, empathy, active listening, a sense of humour, demonstrating security and confidence in oneself, conveying a positive attitude and treating the patient as a part of the team: “People really need to talk a lot and to feel listened to, so, if you know how to listen…” (Female, 42 years, work experience: 20 years).

The ability to provide information and advice was also highly regarded, as this increases the trust in the professional and the feeling that the professional is concerned about the patient's recovery: “Well, anyway, I think it's more about [patient] education, right? Knowing what they have to do at home, what problems the patient may have to face at times… in order for them to know how to resolve this when they are at home” (Male, 46 years, work experience: 22 years)

Positive treatment results were also highly valued, as this has a positive influence on patient satisfaction, thus increasing the level of trust: “Well, how you perform a treatment also [affects the relationship], how they feel after treatment… yes… if they improve, … that and the way you treat them too, of course”. (Female, 44 years, work experience: 22 years).

Physical therapists in this study valued patients with appropriate expectations regarding treatment or progression, meaning that the process begins with achievable objectives, thus there is less frustration if the initial expectations are not met, as exemplified in the following quote: “…the question they always ask you the first day is, for example: “will I walk again?”-… And I say “let's take it day by day. The important thing is that you leave here each day with the feeling that you are taking something with you and that you keep gaining ground, little by little” …. Focus not so much on the end result, but on the path. I get them to focus more on this and it's better this way. (Female, 47 years, work experience: 25 years)

Intimacy, generated during individual treatments in closed rooms was identified by the participants as a positive aspect: “I feel very comfortable when I am there treating the person face to face, mobilizing a wrist, in other words when you can be there, speaking to the person (Female, 52 years. Work experience: 29 years).

Continuity and duration of treatment, the number of sessions leads to the development of a relationship of trust, as described by one of the physical therapists: “If we add the hours that they spend with us during the twenty sessions that are sometimes forty, and sometimes, … in other words, they practically always go over [this number]… then there is already a relationship… we talk a bit about everything”. (Female, 47 years, work experience: 25 years)

Physical therapists feel that the quality of the patient-centred therapeutic relationship does not only depend on themselves, rather it also depends on the patients’ contextual factors, the characteristics of the environment and aspects concerning the organization and coordination of the professional team.

Age seems to be an important factor, as it appears as both a barrier and a facilitator to the establishment of good relationships, as patients perceive that the older a physical therapist is, the more experienced he or she must be. This is in line with findings reported by Roberts et al.,18 who state that the years of experience improve affective communication or the abilities that are required to “care” for others. Thus, physical therapists with greater experience have more affective behaviours which are focused on the patient's emotions and are more amiable.

We understand that the level of intimacy (whether or not this is provided by the organization of the service and related to the amount of physical space) is important in establishing a relationship that is centred on the patient, as this can influence care. Thus, the lack of the same hampers the development of a relationship of trust and confidentiality. Medina-Mirapeix et al.19 and Hush et al.8 have confirmed this by identifying intimacy as an aspect that determines patients’ satisfaction with the quality of the service. The physical therapists themselves understand that, in order to establish a close relationship based on trust, it is important to have personal space available, in which the patient can feel accepted and listened to.

The perception that the professionals’ mood can influence the relationships with their patients is noteworthy. Rios et al.20 affirm that depressive states and emotions, such as sadness, anger, or anxiety, decrease social relations. According to Johnson,21 emotions condition the way we communicate, and how these are recognized and interpreted by others. Just the act of realizing which emotions one is feeling can be crucial in the establishment of a good therapeutic relationship. The solution provided by physical therapists in this study was to “try to avoid others noticing it”, however this lack of authenticity, can be perceived by the patient as being false which makes trust more difficult to achieve. Beck22 affirms that depression includes a negative processing of oneself, one's future and one's environment. Negative states of mind can be perceived as having a negative character, demonstrating insecurity or a lack of self-esteem. According to the physical therapists in this study, these behaviours eventually cause barriers in the patient-centred relationship.

Winning the patients’ confidence seems crucial for achieving a quality therapeutic relationship. Thom affirms that trusting someone else leads to an expectation that that person is going to behave in a favourable manner and, based on this expectation, risks can be taken.23 Confidence influences many therapeutic processes, such as unconditional acceptance,24 therapeutic alliance and the acceptance of therapeutic recommendations.25 Also, confidence improves the patient's feeling of autonomy,26 the improvement of symptoms and an overall satisfaction with the medical care,27 as well as helping shared decision making.28

Physical therapists in this study did not mention the terms: unconditional acceptance and authenticity, as aspects related with the quality of the therapeutic patient-centred relationship. However, we understand that many of the barriers described as the patient's own, such as a dependent personality, low self-effectiveness, age, lack of motivation, prejudices or hidden interests, could be resolved with a greater understanding of the contextual factors and the personality of each patient and, ultimately, with a greater degree of unconditional acceptance. According to the review by Synnott et al.,29 physical therapists only partially recognize the cognitive, psychological, and social factors associated with the disease and pain. Perhaps this is why the participants in this study perceive these factors as patient barriers when they are inherent factors. Once more, we believe that these should be accepted in order to establish a therapeutic patient-centred relationship.

In summary, the findings of this study indicate that the therapeutic relationship is understood by physical therapists as being an important aspect worth considering, although more linked towards the patients’ contextual factors and needs than towards the practice of the profession.

Limitations of the studyThe nature of the data collection system (focus groups) could have led to a bias in the form of emotional contagion among participants. However, the fact that the moderator was sufficiently trained, together with the analysis method, including three independent researchers, should have decreased such bias. Finally, given the sample size and the participation of professionals from only a specific number of public health centres of the Community of Valencia (Spain), we cannot generalize the findings of the results presented in this study.

Implications for practiceIn our opinion, there is a need for further educational programs on the development of therapeutic relationships and for providing strategies for communicating news that are not what the patient expects to hear, as well as improvements in self-knowledge and concerning the emotional regulation of physical therapists. Health managers may use these findings to improve the layout of the rehabilitation gyms, as well as the coordination of all team members. Finally, in future research we feel it is worth studying the perceptions of professionals from different types of centres, geographical areas and sample groups (thus exploring the influence of age or years of experience on physical therapists’ perceptions).

ConclusionPhysical therapists perceive that some of their personal characteristics; the interpersonal ways to relate to the patient; the expectations formed concerning treatment and prognosis; and certain aspects of the context of interaction act as both barriers and facilitators to the establishment of a quality therapeutic relationship.

They also perceive that their lack of training in communication skills, and that certain characteristics, behaviours and prejudices towards the physical therapist, are perceived as barriers. On the other hand, providing information and advice and good treatment results are perceived as facilitators to the establishment of a quality therapeutic relationship.

A greater emphasis on organizational and environmental factors, as well as the improvement of self-awareness, emotional regulation and communication skills on behalf of physical therapists, could facilitate the understanding of the patients’ contextual factors, thus improving the quality of the therapeutic relationship.

FundingThis study was funded by a research grant from CEU-Banco Santander (Ref. SANTANDER/PRCEU-UCH06/22), Spain.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest