Secondary analysis of data from a randomized controlled trial.

BackgroundTreatment based on the Movement System Impairment-Based classification for chronic low back pain results in the same benefit when compared to other forms of exercise. It is possible that participant's characteristics measured at baseline can identify people with chronic low back pain who would respond best to a treatment based on the Movement System Impairment model.

ObjectivesTo assess if specific characteristics of people with chronic low back pain measured at baseline can modify the effects of a treatment based on the Movement System Impairment model on pain and disability.

MethodsFour variables assessed at baseline that could potentially modify the treatment effects of the treatment based on the Movement System Impairment model were selected (age, educational status, physical activity status and STarT back tool classification). Separate univariate models were used to investigate a possible modifier treatment effect of baseline participant's characteristics on pain and disability after the treatment. Findings of interaction values above 1 point for the outcome mean pain intensity or above 3 points for disability (Roland Morris questionnaire) were considered clinically relevant.

ResultsLinear regression analyses for the outcomes of pain and disability did not show interaction values considered clinically relevant for age, educational status, physical activity status and STarT back tool classification.

ConclusionAge, educational status, physical activity status and STarT back tool classification did not modify the effects of an 8-week treatment based on the Movement System Impairment model in patients with chronic low back pain.

Registered at www.clinicaltrials.gov: NCT02221609 (https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02221609).

Low back pain (LBP) is the most prevalent musculoskeletal disorder1 and the leading cause of disability worldwide.2 LBP is recurrent in nature3–6 although the exact estimates of risk of LBP recurrence are unknown.7 Exercise is usually a consistent recommendation for treating chronic LBP across different guidelines8 resulting however in only modest effects on pain and disability.9 Several classification systems have been described to guide the treatment of LBP trying to increase the treatment effects.10–15

The Movement System Impairment based classification (MSI) model is a classification system available to guide the treatment of different musculoskeletal disorders including chronic LBP.14,16,17 MSI classification procedure involve interpreting different tests of alignments and movements. Data from timing and magnitude of movement and presence of pain during each test allows the therapist to classify the patient into one of the MSI syndromes. After the classification procedure, treatment is based on correcting the alignment and movement impairments associated with each specific MSI syndrome through patient education, analysis and correction of daily activities and prescription of specific exercises.14,16,17

The efficacy of a treatment based on the MSI model for chronic LBP has been tested in some randomized controlled trials resulting however in the same benefit when compared to other forms of exercise.18–20 In a recent clinical trial,20,21 treatment based on the MSI model against a treatment based on stretching and strengthening exercise in people with chronic LBP were compared in a high-quality randomized controlled trial. The results of this study showed that patients with chronic LBP had similar improvements in pain, disability and global impression of recovery after participating in a treatment based on the MSI model or a treatment based on stretching and strengthening exercises with a 6-month follow-up. However, this study20 did not investigate if participant's characteristics measured at baseline could identify people with chronic LBP who would respond best to a treatment based on the MSI model. This information might help physical therapists, health care providers and people with chronic LBP in choosing between a treatment based on the MSI model or a treatment based on stretching and strengthening exercises.

The objective of the current study was to assess if specific characteristics of people with chronic LBP measured at baseline can modify the effects of a treatment based on the MSI model on pain and disability when compared to a treatment based on stretching and strengthening exercises.

MethodsStudy designThis study was a secondary analysis of data from a randomized controlled trial comparing the efficacy of a treatment based on the MSI model with a treatment based on stretching and strengthening exercises people with chronic LBP.20,21

ParticipantsA total of 148 participants of both sexes, between 18 and 65 years of age with non-specific LBP for more than three months and a current minimum pain intensity of three on an 11-point numeric pain rating scale participated in this study. Inclusion criteria also included to be able to stand and walk independently and be literate in Portuguese. Participants were excluded if they presented any contraindications to exercise according to the guidelines of the American College of Sports Medicine,22 serious cardio-respiratory diseases, previous spinal surgery, serious spinal pathologies (fractures, tumors or inflammatory pathologies), nerve root compromise (diagnosed by clinical examination of sensibility, power and reflexes), major depression,23,24 pregnancy or if they could not be classified into one of the five categories of the MSI model.14,25

All participants received information about the study and signed the informed consent form. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Pontificia Universidade Catolica de Minas Gerais, Belo Horizonte, MG, Brazil (CAAE 17660913.0.0000.5137) and it was prospectively registered at www.clinicaltrials.gov (NCT02221609).

Randomization and interventionsParticipants were randomly allocated into one of the two treatment groups (treatment based on the MSI model or treatment based on stretching and strengthening exercises) by using a randomization schedule performed in Excel for Windows. Both groups participated in an 8-week treatment program consisting of 12 physical therapy sessions supervised by two trained physical therapists (one physical therapist for each group).

Treatment based on the MSI model14,16,17 included patient education, analysis and modification of performance of daily activities and specific exercises based on the classification of the participants into one of five possible categories (flexion, extension, rotation, flexion and rotation or extension and rotation) according to the MSI model. The treatment also included a home exercise program that should be performed at least once a day when no treatment sessions were scheduled.

Treatment based on stretching and strengthening exercises26,27 included stretching exercises addressing the lumbar, abdominal and lower limbs muscles and strengthening exercises involving the abdominal and paraspinal muscles.28,29 The treatment also included a home exercise program that should be performed one or two days a week, in addition to the treatment session days.

Outcome measuresMean pain intensity and disability after the treatment (eight weeks after randomization) were selected as the main outcome measures of this study. Mean pain intensity was assessed using a numeric pain rating scale (NRS).30,31 Disability was assessed using the Roland Morris Disability Questionnaire.30–33 The outcome measures have been translated and cross-culturally adapted into Brazilian Portuguese30–32 and are considered as the most important outcome measures for back pain patients.34

Variables of interestFour variables assessed in baseline that could potentially modify the treatment effects of the treatment based on the MSI model were selected based on theoretical rationale: age, educational level, physical activity status and STarT back screening tool classification.35–37

AgeTreatment based on MSI model is based on modification of impaired movements and postures that are supposed to be associated with LBP symptoms. The motor skills required to perform the exercises and activities in the MSI based treatment may be considered more challenging when compared to the exercises prescribed in the treatment based on stretching and strengthening exercises. Because motor skills are expected to gradually deteriorate with age,38,39 the hypothesis of this study was that younger people would respond better to the treatment based on MSI model compared to treatment based on stretching and strengthening exercises.

Educational statusBecause cognitive-motor learning is influenced positively by educational status,40 the hypothesis of this study was that people with higher educational status would respond better to the treatment based on the MSI model. Cognitive-motor learning seems more important to perform exercises and activities associated to the treatment based on MSI model compared to the performance of the exercises associated with treatment based on stretching and strengthening exercises.

Physical activity statusDifferent forms of exercise can induce hypoalgesia and improve function through conditioned pain modulation,41,42 reduction of systemic inflammation found in chronic pain conditions,43–45 reduced fear avoidance beliefs, and interrupting the cycle of pain, disuse and deconditioning.46 The hypothesis of this study was that people who were physically active before treatment would respond better to treatment based on the MSI model because a different treatment component (modification of impaired movements and postures) was added. On the contrary, people who were physically active before treatment may respond worst to the treatment based on stretching and strengthening exercises because this treatment program may be just adding more exercise to a person who is already involved in some form of exercise.

STarT back screening classificationThe STarT back screening tool allows the identification of prognostic indicators in people with LBP in primary care. It categorizes people with LBP into one of three categories, suggesting the best management options for each subgroup: low risk (analgesia, advice and education), medium risk (evidence-based physical therapy) and high risk (combination of physical therapy and cognitive-behavioral therapy).35–37 Because treatment based on the MSI model is more tailored to a kinesiopathologic approach14,16,17 than to a psychosocial approach, the hypothesis of this study was that the participants classified as a low or medium risk according to the STarT back screening tool would respond better to the treatment based on the MSI model compared to treatment based on stretching and strengthening exercises.

Statistical analysisSeparate univariate models were used to assess a possible modifier treatment effect of four baseline participant's characteristics (age, educational level, physical activity status and STarT back screening classification) on pain and disability after a treatment based on the MSI model and treatment based on stretching and strengthening exercises. This subgroup analysis was performed according to the approach recommended by previous research.47,48

Age was dichotomized by using the median split as performed in a previous study.49 The other variables were dichotomized as follows: educational level (university and graduate degree versus elementary degree and high school), physical active status (physically active versus physically inactive), STarT back screening classification (low and medium risk versus high risk).

Because subgroup analysis usually requires larger sample sizes compared to randomized controlled trials investigating main effects,50 the main interest of this study was to look at the estimated effect sizes rather than statistical significance as suggested by other studies.49,51 Findings of interaction values above 1 point for the outcome mean pain intensity (NRS) or above 3 points for disability (Roland Morris questionnaire) were considered clinically relevant.49 In this case, the analysis was followed by calculating the marginal means for the subgroups.52 IBM SPSS 19 statistical package for Windows (IBM Corp, Armonk, New York) was used for the analyses.

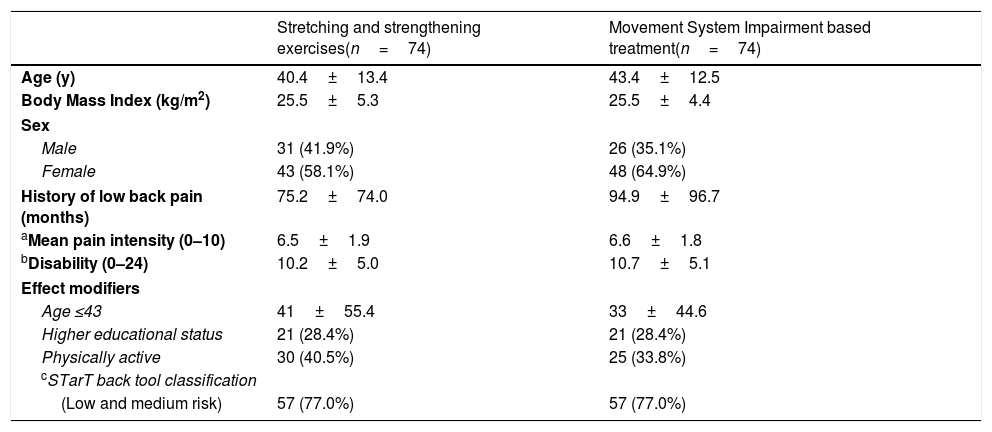

ResultsA total of 231 participants volunteered to participate in the study. After the initial assessment, 83 participants were excluded. A total of 148 participants were assessed at baseline and participated in this study. After the treatment, 145 participants completed the 2-month follow-up assessment (treatment based on the MSI model, n=71 and treatment based on stretching and strengthening exercises, n=74). Participants’ characteristics and potential effect modifiers at baseline are presented in Table 1.

Participants’ characteristics and potential effect modifiers at baseline.

| Stretching and strengthening exercises(n=74) | Movement System Impairment based treatment(n=74) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (y) | 40.4±13.4 | 43.4±12.5 |

| Body Mass Index (kg/m2) | 25.5±5.3 | 25.5±4.4 |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 31 (41.9%) | 26 (35.1%) |

| Female | 43 (58.1%) | 48 (64.9%) |

| History of low back pain (months) | 75.2±74.0 | 94.9±96.7 |

| aMean pain intensity (0–10) | 6.5±1.9 | 6.6±1.8 |

| bDisability (0–24) | 10.2±5.0 | 10.7±5.1 |

| Effect modifiers | ||

| Age ≤43 | 41±55.4 | 33±44.6 |

| Higher educational status | 21 (28.4%) | 21 (28.4%) |

| Physically active | 30 (40.5%) | 25 (33.8%) |

| cSTarT back tool classification | ||

| (Low and medium risk) | 57 (77.0%) | 57 (77.0%) |

Continuous variables are expressed as mean ±standard deviation.

Categorical variables are expressed as n (%).

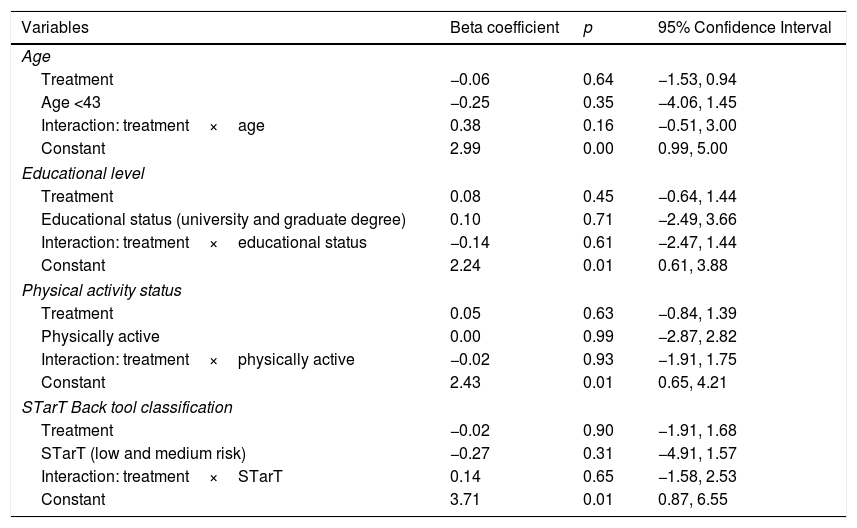

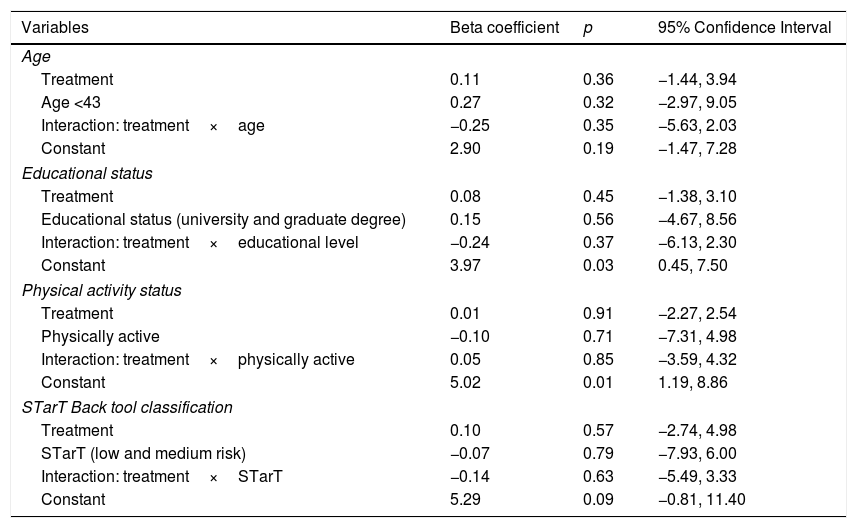

Linear regression analyses for the outcomes of pain and disability did not show interaction values considered clinically relevant (>1 point for pain and >3 for disability) for any of the potential effect modifiers: age, educational status, physical activity status and STarT back tool classification (Tables 2 and 3).

Linear regression analysis for pain.

| Variables | Beta coefficient | p | 95% Confidence Interval |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | |||

| Treatment | −0.06 | 0.64 | −1.53, 0.94 |

| Age <43 | −0.25 | 0.35 | −4.06, 1.45 |

| Interaction: treatment×age | 0.38 | 0.16 | −0.51, 3.00 |

| Constant | 2.99 | 0.00 | 0.99, 5.00 |

| Educational level | |||

| Treatment | 0.08 | 0.45 | −0.64, 1.44 |

| Educational status (university and graduate degree) | 0.10 | 0.71 | −2.49, 3.66 |

| Interaction: treatment×educational status | −0.14 | 0.61 | −2.47, 1.44 |

| Constant | 2.24 | 0.01 | 0.61, 3.88 |

| Physical activity status | |||

| Treatment | 0.05 | 0.63 | −0.84, 1.39 |

| Physically active | 0.00 | 0.99 | −2.87, 2.82 |

| Interaction: treatment×physically active | −0.02 | 0.93 | −1.91, 1.75 |

| Constant | 2.43 | 0.01 | 0.65, 4.21 |

| STarT Back tool classification | |||

| Treatment | −0.02 | 0.90 | −1.91, 1.68 |

| STarT (low and medium risk) | −0.27 | 0.31 | −4.91, 1.57 |

| Interaction: treatment×STarT | 0.14 | 0.65 | −1.58, 2.53 |

| Constant | 3.71 | 0.01 | 0.87, 6.55 |

Linear regression analysis for disability.

| Variables | Beta coefficient | p | 95% Confidence Interval |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | |||

| Treatment | 0.11 | 0.36 | −1.44, 3.94 |

| Age <43 | 0.27 | 0.32 | −2.97, 9.05 |

| Interaction: treatment×age | −0.25 | 0.35 | −5.63, 2.03 |

| Constant | 2.90 | 0.19 | −1.47, 7.28 |

| Educational status | |||

| Treatment | 0.08 | 0.45 | −1.38, 3.10 |

| Educational status (university and graduate degree) | 0.15 | 0.56 | −4.67, 8.56 |

| Interaction: treatment×educational level | −0.24 | 0.37 | −6.13, 2.30 |

| Constant | 3.97 | 0.03 | 0.45, 7.50 |

| Physical activity status | |||

| Treatment | 0.01 | 0.91 | −2.27, 2.54 |

| Physically active | −0.10 | 0.71 | −7.31, 4.98 |

| Interaction: treatment×physically active | 0.05 | 0.85 | −3.59, 4.32 |

| Constant | 5.02 | 0.01 | 1.19, 8.86 |

| STarT Back tool classification | |||

| Treatment | 0.10 | 0.57 | −2.74, 4.98 |

| STarT (low and medium risk) | −0.07 | 0.79 | −7.93, 6.00 |

| Interaction: treatment×STarT | −0.14 | 0.63 | −5.49, 3.33 |

| Constant | 5.29 | 0.09 | −0.81, 11.40 |

The objective of this study was to investigate if specific baseline characteristics in patients with chronic LBP (age, educational status, physical activity status and STarT back tool classification) could modify the effects of a treatment based on the MSI model compared to a treatment based on stretching and strengthening exercise on pain and disability. We did not observe any clinically relevant influence53 of those baseline characteristics on the effects of a treatment based on the MSI model after an 8-week treatment program.

Because the current study was underpowered to perform a subgroup analysis, the interpretation of the results was based on the treatment effect modifier sizes represented by the results of interaction tests rather than statistical significance. Although interaction effect values were not exactly equal to treatment effect, the size of interaction can quantify the additional benefit the participants in a specific subgroup would get from treatment when they were compared with those not in this subgroup.52 The size of interaction found in all analyses were very small with all interaction values being close to zero (−0.25 to 0.38) (Tables 2 and 3).

The hypothesis of this study was that younger people, with higher educational status, who are physically active and with a STarT back tool classification of low or medium risk would benefit more from a treatment based on the MSI model compared to a treatment based on stretching and strengthening exercises. Although several other baseline characteristics were assessed in baseline, we only included a few number of variables based on theoretical rationale or indirect evidence supporting the hypothesized interaction as suggested by other studies.47,48

There are limited number of randomized controlled trials investigating the effect of a treatment based on the MSI model in people with chronic LBP.18–20 To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to investigate if baseline characteristics of people with chronic LBP could influence the effects of a treatment based on the MSI model on pain and disability. Van Dillen et al.18 showed that higher adherence to daily activity performance is associated with greater effect of a treatment based on the MSI model on function but the authors did not assess the influence of baseline characteristics in their analyses. Other studies have investigated the influence of age, educational status and STarT back screening classification as a potential treatment modifier on different outcomes and conditions. Garcia et al.49 showed that older people with chronic LBP respond better to Mechanical Diagnosis and Treatment compared to Back School. Being younger, however, resulted in greater improvement after a cognitive-behavioral treatment for LBP.54 According to Oliveira et al.,55 age influenced pain intensity and disability in people with chronic LBP after four weeks of treatment. However, this association was not clinically important. Jain et al.56 reported better outcomes of nonoperative treatment of rotator cuff tears when people have at least a college education. Patients with acute LBP classified as high risk by the STarT Back screening tool respond better to early physical therapy intervention than usual care (only patient education).57

Based on the results of the current study, we cannot recommend choosing between treatment based on the MSI model and treatment based on stretching and strengthening exercises for people with chronic LBP by using baseline characteristics of age, educational status, physical activity status and STarT back tool classification. Because treatment based on the MSI model for chronic LBP has been shown to result in the same improvement when compared to other forms of exercise,18–20 choosing between both treatments should be based on patient and therapist preferences.

Limitations of the present study included not having equally sized groups positive and negative for all the potential effect modifiers and the low statistical power associated with secondary analysis of data from randomized controlled trials.51,52 Results of the primary analysis of the current trial showed that the mean differences in pain and disability between groups were very close to zero.20 This is a potential limitation of the secondary analysis performed in the current study as the chances of detecting treatment effect modification when the main effect achieves the null hypothesis are very unlikely.52 However, other studies have described baseline characteristics in people with chronic LBP that can modify the effect of different treatments even when the main effect of treatment was close to zero.49,58 Future studies with larger sample sizes should investigate whether other characteristics of people with chronic LBP can modify the effects of a treatment based on the MSI model.

ConclusionAge, educational status, physical activity status and STarT back tool classification did not modify the effects of an 8-week treatment based on the MSI model in patients with chronic LBP.

AcknowledgementsAt the time of the study, the first author was a doctoral candidate funded by Coordenacao de Aperfeicoamento de Pessoal de Nıvel Superior (CAPES). This study was funded by Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Cientifico e Tecnologico/Brazil (CNPQ grant number 470273/2013-5).

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.